Southern California

Regional Freight Study

Executive Summary

As part of a process to enrich the national dialogue about freight

transportation issues, needs, and potential program options, the Federal

Highway Administration’s (FHWA) Office of Freight Management and

Operations has undertaken a series of case studies. This report presents

the results of a case study undertaken in Southern California (the Los

Angeles metropolitan area). Southern California is home to the nation’s

largest container port complex, a major air cargo center, a West Coast

rail hub, and numerous regional distribution centers. As the second

largest metropolitan area in the U.S., Southern California also represents

one of the largest local markets for freight services in the country.

The volume and complexity of freight movements in the region are enormous.

The institutional environment for freight planning in Southern California

is also extremely complex. Within this complex region much is being

done to address freight issues. Yet many of the participants in this

case study agree that the challenges the region faces in the future

will require substantial resources and innovative approaches that are

still being developed.

Freight movement in Southern California consists of three major markets:

1) regional and local distribution, 2) domestic trade and national distribution,

and 3) international trade. Southern California provides a huge internal

market for goods and services. Based on the Freight Analysis Framework,

FHWA estimated that over 223 million tons of freight were shipped internally

within the Southern California region – approximately 30 percent

of the total freight shipped in the region. Southern California is

also one of the leading manufacturing centers in the nation, generating

shipments for domestic trade with the rest of the U.S. The six-county

region ranks fourth in the nation, behind only California, Ohio, and

Texas, in total manufacturing jobs. Shipments between Southern California

and the rest of the country account for 447 million tons, or over 60

percent of freight shipped in the region. Southern California is also

a large gateway for international trade. Over 11 percent of the

nation’s trade (by value) passes through the region and it collects

over 37 percent of the nation’s import duties.

In order to meet its freight transportation needs, the Southern California

transportation network has developed and invested in international gateway

facilities (such as the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and the

international airports of Los Angeles and Ontario), interstate multi-modal

corridors (including several major interstate highways and the transcontinental

rail lines operated by the Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa

Fe railroads), and a vast metropolitan roadway system.

As Southern California grapples with its freight transportation needs,

it plans within the context of a number of major regional issues. These

include:

- Growth – Southern California continues to be

a major population and employment growth region, fueling demand for

freight transportation services. According to the Southern California

Association of Governments, freight transportation demand is expected

to grow by 80 percent between 1995 and 2020.

- Congestion – Southern California has some of the

most congested highway, rail, and airport facilities in the country.

This creates substantial delays for all users of the transportation

system and imposes costs on goods shipped through the regional freight

transportation system.

- Air Quality – Much of Southern California is within

severe non-attainment areas for national air quality standards. Any

new system capacity must justify that it will not negatively change

air quality, which may serve as major constraint to growth in the

freight transportation system.

- Security – In the aftermath of the events of September

11th, increasing attention is being paid to freight transportation

security, especially at international ports of entry.

- Safety – Provision of a safe transportation system

is a major goal of regional planning. However, the interaction of

passenger and freight transportation creates significant safety concerns,

especially on high truck volume freeways and at rail-highway crossings.

- Land Use – High land costs in the developed areas

surrounding ports, airports, intermodal terminals, and truck terminals

have forced the freight transportation industry to look to outlying

areas for facility growth. This coupled with the region’s sprawling

development patterns has caused regional freight distribution patterns

that emphasize peak period congestion and high levels of freight vehicle-miles

traveled.

- Regional Governance and Institutional Complexity –

Southern California includes four district offices of the state

department of transportation, 14 subregional councils of government,

six county transportation commissions that program transportation

funds, and 184 cities. Needless to say, this is an extremely difficult

environment within which to plan for freight transportation systems

that transcend multiple jurisdictional boundaries within the region.

Despite these challenges, the region has enjoyed numerous successes

in addressing freight transportation needs. Successes have included

both major capital projects as well as planning process/institutional

relationships. Perhaps the best known of these successes is the Alameda

Corridor, which brought together cities, ports, and railroads in a unique

public-private partnership of epic proportions. Lesser known, but equally

important, successes are present throughout the region.

The experiences of Southern California illustrate a number of themes

that should be the focus of freight policy discussions throughout the

nation. These fall into two broad categories: funding/financing and

institutional/planning process.

Funding/Financing

- Adequacy of Resources – Southern California has

enormous transportation funding needs, but freight transportation

projects will need to compete with all other projects for local funding

resources. Freight projects, particularly international gateway projects,

tend to be expensive and their local benefits are considered to be

relatively low when compared to development costs. With a transportation

programming process that largely focuses locally, broad freight projects

will continue to face an uphill battle for funding. This suggests

that major gateway and mutli-modal interstate corridor projects will

need to include partnerships with state and federal agencies, find

new revenue sources that are increasingly user-fee oriented, and look

for greater flexibility in use of federal surface transportation funds

in the next reauthorization.

- Burden Sharing and Fairness: The Distribution of Costs and Benefits –

Southern California maintains freight transportation facilities

that have regional, statewide, and national significance. The benefits

of these facilities are felt throughout the U.S., but the transportation

effects of these facilities are greatest at the local level. The

question of who pays and who benefits from improvements in these facilities

requires national attention and may imply a need for new federal and

state funding programs, i.e., local users bear the cost for dispersed

national benefits.

- Innovative Financing and User Fees – Given the

enormous transportation funding needs in Southern California and the

benefits of freight transportation projects to the private sector,

it is not surprising that planners will look to user fees as a source

of financing for freight transportation improvements. The Alameda

Corridor is one of the most often cited examples of how user fees

can play a critical role in financing major freight projects. But

not all freight projects in Southern California will be able to rely

on user fee financing. Initial evaluations of tolling options for

truck lanes in Southern California show that they may not produce

sufficient revenues to support project financing. Beneficiaries of

freight improvements, particularly on highways, include non-freight

interests and they need to pay their share of costs. In addition,

user fees may reduce the competitive position of regional freight

facilities as compared to ports and intermodal facilities elsewhere

in the U.S.

- Public Investment in Private Freight System – While

a substantial volume of freight is moved on public highway systems,

there is increasing interest in expanding the role of private systems,

such as using railroads or barge activities to alleviate highway congestion.

The Metrolink project in Southern California is a good example of

how public passenger rail projects can be used to benefit rail freight

capacity needs. But the limited flexibility of existing funding sources

and the difficulties associated with justifying public investment

in private systems are obstacles that will need to be addressed in

the future.

Institutional/Planning Process

- Regional Coordination and Decision-Making – Freight

projects do not respect jurisdictional boundaries. Thus, freight

projects tend to require the coordination of numerous local and regional

agencies. In an area as complex as Southern California this creates

an extremely complex planning process for freight projects. In addition,

achieving multi-jurisdictional consensus on regional freight priorities

is very difficult. New institutions are needed to address these multi-jurisdictional

issues. The joint powers agency created for the Alameda Corridor

is an example of one type of institution used to create cooperative

working arrangements. Other forums like the regional Goods Movement

Advisory Committee, that brings different governmental agencies together

to develop a consensus regarding planning objectives, are also important.

- Public-Private Collaboration – Freight planning

requires the coordination of public and private sector interests.

Yet public agencies plan on a long-term (20-25 years) basis, while

private agencies plan on a much more immediate basis. For private

businesses that must devote as much of their resources as possible

to revenue generating activities, the public sector planning process

is complex and cumbersome. There is also a longstanding mistrust

between public and private sectors in the freight industry due to

concerns regarding regulatory relationships. The region needs standing

institutions to bring public and private sector freight organizations

together to tackle the short term and long term needs of the freight

transportation system.

- Private-Private Collaboration – In Southern California,

there is tremendous potential for resolving freight transportation

issues through operational strategies. These include making better

use of existing capacity through more coordinated time of day operations.

But to affect this change, private companies who are fiercely competitive

must work together, and recognize that the public sector clearly has

a role to play in facilitating this cooperation. Removing regulatory

obstacles (such as night-time operating restrictions) and providing

economic inducements (such as congestion fees charged at terminal

gates for peak period operations) are potential alternatives that

could be explored.

- Public Awareness – Citizen groups often line up

against freight interests in the local planning process. This has

been an issue for air cargo and port access projects in Southern California.

Yet freight transportation demands are derivative of the public’s

demand for goods and service. Much needs to be done to educate the

public as to the benefits of efficient goods movement.

- Data Modeling and Tools – Critical decisions about

freight transportation face local agencies in Southern California

and these agencies have taken major steps to develop the tools necessary

to evaluate alternative transportation investments and policies.

Yet many of these tools rest on flimsy methodologies and insufficient

data. Information about freight movement in a metropolitan area is

difficult to obtain due to the proprietary nature of much of these

data. The Federal government can play a role in developing techniques

and data for local freight planning that would assist in local decision-making.

- Coordination of ITS – ITS presents tremendous

potential for improving the efficiency of goods movement. However,

for this potential to be realized it will require a greater level

of cooperation and interface between public and private information

systems. ITS intermodal demonstrations at the Port of Long Beach

are beginning to tackle the problem of how to bring these public and

private information systems together to produce good traveler and

traffic management information. Building on this program and other

ITS projects in other parts of the region would be beneficial.

1. Case Study Introduction

The Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) Office of Freight

Management and Operations invited stakeholders from five areas across

the country to examine how different regions are addressing freight

transportation needs. These case studies were selected to illustrate

different types of freight activity, institutional complexity, and approaches

to problem solving. Together, these case studies help tell the national

“freight story.”

Southern California (the Greater Los Angeles Metropolitan region) presents

a particularly informative example. The region is home to the nation’s

largest container port complex, a major air cargo center, a West Coast

rail hub, and numerous regional distribution centers. As the second

largest metropolitan area in the U.S., Southern California also represents

one of the largest local markets for freight services in the country.

The volume and complexity of freight movements in the region are enormous.

The institutional environment for freight planning in Southern California

is also extremely complex. Within the region much is being done to

address freight issues. Yet most agree that the challenges the region

faces in the future will require substantial resources and innovative

approaches that are still being developed.

This report summarizes the results of a case study conducted by major

freight transportation stakeholders in Southern California.[1]

The report begins with a brief description of the characteristics of

freight movement and the freight transportation network in Southern

California. Freight transportation in the region serves three distinct

markets: international trade, domestic trade, and regional/local distribution.

To serve these markets, the regional freight transportation network

consists of three types of facilities playing the roles of international

gateways, elements of a statewide/multi-state transport network, and

a system of local roads and connector facilities that aid in local and

regional distribution systems.

After describing Southern California freight transportation, the report

describes some of the critical factors and issues that influence freight

transportation planning and management in the region. These issues

include regional economic/population growth, congestion on transportation

facilities, air quality concerns, land use issues/conflicts, and regional

governance and institutional complexity.

Southern California has often succeeded in addressing freight transportation

needs within this context of regional issues and concerns. The report

provides some examples of how the region has dealt with its diverse

freight transportation needs. Examples of capital project successes,

institutional/planning successes, and funding/resource successes are

also examined.

The remainder of the report describes lessons learned from the region’s

experience and describes challenges for the future. These can be broadly

categorized as institutional/planning process-related or funding/resource-related.

The analysis suggests areas where various freight transportation partners

in private sector, regional and local government agencies, state government

agencies, and the federal government will need to work together to shape

the region’s future freight transportation system. An analysis

of the challenges related to many topics, including funding/financing,

regional coordination and decision-making, institutional partnerships,

public awareness of freight issues, development of data and analytical

tools, and implementation and coordination of information technology

and intelligent transportation systems (ITS), is also discussed.

While the region has undertaken a number of freight movement studies

(including an interregional goods movement study, a number of subregional

goods movement reports, and numerous analyses of corridors and specific

freight-related projects), this case study provided a unique opportunity

to take a big picture look at regional freight issues. By examining

not only how regional freight issues manifest themselves within the

broader regional transportation picture, but also where past efforts

have resulted in successful programs and projects, and finally where

challenges remain, local stakeholders have been able to discuss the

region’s freight future from a new perspective.

2. An Overview of Existing Freight Movement Patterns in Southern

California

Southern California – the counties of Los Angeles, Orange,

Riverside, San Bernardino, Imperial, and Ventura that comprise the metropolitan

planning organization (MPO) region of the Southern California Association

of Governments (SCAG) – is the second largest metropolitan

region in the United States. The population in the region is over 16.5 million

people, up two million from 1990, according to census reports. In addition,

the Southern California economy generates over seven million jobs, mostly

in the trade and transportation, manufacturing, and tourism industries.

Freight Movement in Southern California

Freight movement in Southern California consists of three major and

distinct freight markets:

- regional and local distribution,

- domestic trade and national distribution, and

- international trade.

Figure 2.1 provides some perspective on the magnitude of each

of these components of the regional freight movement picture and how

this is projected to change in the future. This figure shows the amount

of tonnage carried by each freight mode in each of the three market

segments in 1998 and forecasted for 2020. The data for international

trade shows the mode used to move these cargoes to/from their domestic

markets through Southern California gateways, not necessarily the mode

used to carry the product into or out of the United States. In 1998,

over 735 million tons of freight moved into, out of, and within Southern

California (FHWA Freight Analysis Framework Database, 2002). Key features

of Southern California freight markets are summarized below.

Regional and Local Distribution

- The enormous population and economic base creates a massive internal

market for local/regional distribution and creates a critical mass

of freight transportation facilities.

- Over 30 percent of the freight tonnage moved in Southern California

remained within the six county region (see Figure 2.1)

- The region is home to 32,538 wholesale trade establishments and

7,345 trucking firms.

- The region ranks second among U.S. metropolitan areas for wholesale

trade employment and sixth in wholesale trade share of total employment.

Figure 2.1 Freight in the SCAG Region (Millions

of Tons)

Source: Federal Highway Administration, Office of Freight Management

and Operations, Freight Analysis Framework.

Domestic Trade and National Distribution

- The Los Angeles MSA is one of the leading manufacturing centers

in the country, shipping $20 billion in manufactured goods and providing

roughly one million manufacturing jobs in 1997 (more than the entire

state of Michigan).

- The six county region ranks fourth in total manufacturing jobs behind

the entire state of California, Ohio, and Texas.

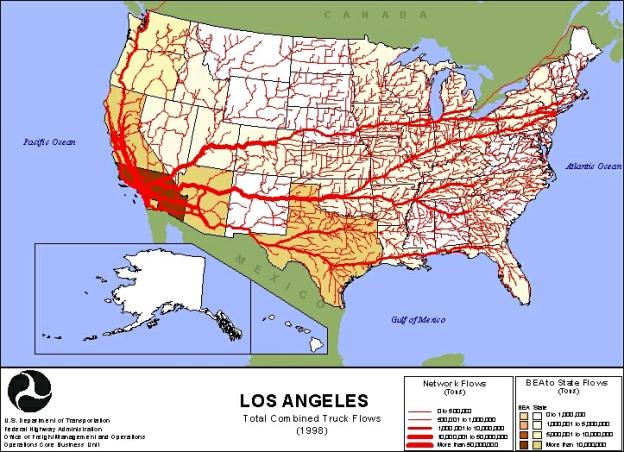

- Figure 2.2 illustrates commodity flows between Southern California

and its local, regional and national markets. The map was developed

in the Freight Analysis Framework, and shows the movement of freight

that has either an origin or destination within the Southern California

area. (Freight shipments that travel the area but do not actually

have an origin or destination within the region are not represented.)

This illustrates the importance of both domestic and international

trade shipments between Southern California and the rest of the U.S.

and the need for effective transportation networks to link the region's

economy to the rest of the United States.

Figure 2.2 Los Angeles Total Truck Flows (1998)

International Trade

- According to the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation,

$230 billion of international trade cargoes moved through the region’s

ports of entry in 2000. This accounted for over 11 percent of

the nation’s international trade and generated 37 percent of

all import duties.

- International trade accounted for approximately 9 percent of the

total tonnage moved into and out of Southern California in 1998 (see

Figure 2.1).

- International trade is the fastest growing segment of the Southern

California freight picture, with expected growth to 14 percent of

total tonnage moved in the region by 2020 (see Figure 2.1).

The Freight Transportation Network in Southern California

In order to support its freight transportation markets, Southern California

has developed an extensive infrastructure of international gateway facilities,

interstate multimodal corridors, and a metropolitan roadway and distribution

network.

International Gateways

Southern California has made substantial investments in infrastructure

to service international trade through its airports and maritime ports.

The region is a major air cargo center, home to two international and

six commercial airports. Most of the region’s air cargo moves

through Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), making it the third

busiest air cargo facility in the world. Air cargo is critical for

many manufacturing operations both in the U.S. and abroad, and the high-value

cargo typically shipped by air explains why LAX handles more exports

by dollar value ($36.5 billion in 1997) than the nearby Ports of

Long Beach and Los Angeles ($35.2 billion).

Southern California is home to three international deepwater port facilities

that comprise the Los Angeles Customs Region. The Ports of Los Angeles

and Long Beach, respectively the first and second largest container

port facilities in the United States, together form the third largest

container port complex in the world. Their share of West Coast container

cargo is an astounding 50 percent and growing, and they handle

35 percent of all waterborne cargo in the U.S. The Port of Hueneme,

the only deepwater harbor between Los Angeles and the San Francisco

Bay Area, has developed to serve a core niche. It is the top seaport

in the United States for citrus exports and ranks among the top 10 ports

in the country for imports of automobiles and bananas.

Interstate Multimodal Corridors

An extensive network of multimodal facilities has developed in order

to link the large cargo volumes of both domestic and international trade

moving between Southern California and the rest of the country. The

regional air cargo system also serves the domestic trade system. Southern

California is a major rail hub with both Western Class I railroads

operating on mainlines that connect the region to the national rail

network. The region includes six rail-truck intermodal facilities,

including Burlington Northern Santa Fe’s (BNSF) Hobart Intermodal

Facility, the busiest in the U.S. (handling over 90,000 lifts per month).

There are three major interstate highway corridors in the region: I-5

(providing linkages to the rest of the West Coast of the U.S., Canada,

and Mexico); I-15/I-40 (providing links to the interior U.S.); and I-10

(the “Southwest Passage” to the rest of the Sun Belt).

Each of these interstates ranks among the highest truck volume corridors

in the Western U.S.

Metropolitan Roadway System

Southern California is famous for its freeway system, which functions

as the backbone for the extensive local distribution network that serves

the regional economy. As of 1997, Southern California was home to 8,906

miles of freeways; 14,998 miles of principal arterials; 17,605 miles

of minor arterials; and 8,262 miles of major collectors. This system

includes critical access routes to the ports, airports, and rail intermodal

facilities.

3. Regional Concerns that Influence Freight Planning and Management

in Southern California

Freight transportation has helped facilitate the enormous economic

success Southern California has enjoyed throughout its history. Looking

to the future, this metropolitan area must determine how it will balance

the needs of a growing economy and population with an increasingly constrained

transportation system. Decision-makers at the state and local level

are beginning to craft innovative strategies for addressing freight

transportation needs, with an initial focus on trade gateways and corridors

of statewide and regional significance. An example of these innovative

approaches is the Global Gateways Development Program (SCR 96, Karnette),

a state program that calls on the state’s Department of Transportation

(Caltrans) to develop strategies and funding programs to improve those

key transportation facilities that provide access to trade gateways.

In its report to the legislature as mandated by SCR 96, Caltrans identified

a number of issues that will influence freight transportation priorities

in California in the future. Most of these issues will also drive freight

transportation planning in Southern California.

Growth heads the list of regional issues that will face freight transportation

planners in the future. The question for Southern California is how

to accommodate economic and transportation growth in the context of

heavily congested transportation facilities, regulatory constraints

posed by the region’s air quality non-attainment status, increasing

concerns about transportation safety and security, growing land use

conflicts and constraints, and the complexity of regional governance

and institutional relationships.

Growth

Fueled by the continuing economic growth of the region and the increasing

importance of international trade in the national economy, goods movement

traffic in Southern California by all modes is projected to increase

by over 80 percent between 1995 and 2020, according to studies

conducted for SCAG. More recent freight forecasts by the FHWA project

that domestic freight flows in Southern California will grow at a higher

rate than the national growth rate (83 percent growth in Southern

California between 1998 and 2020 as compared to 71 percent growth nationally).

International freight traffic in Southern California is projected to

grow at a substantially higher rate than international freight will

grow for the nation as a whole (170 percent growth in Southern

California between 1998 and 2020 as compared to 98.7 percent growth

in the rest of the nation).

Figure 3.1 illustrates the growth in freight tonnage by mode projected

by SCAG. The Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) forecasts over 65 percent

increase in regional heavy-duty truck traffic by 2020. SCAG studies

project rail tonnage in Southern California to increase by more than

240 percent between 1995 and 2020, due in large part to international

trade growth and connections to the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

Air cargo is expected to be the fastest growing component of the regional

goods movement picture, with growth of over 300 percent in tonnage projected

by SCAG between 1995 and 2020. Other studies forecast the strong growth

in marine cargoes will continue into the future. Port projections show

increases to between 25 million and 36.1 million 20-foot equivalent

units (TEUs) by 2025 from current levels of 9.5 million TEUs.

Figure 3.1 Freight Forecasts by Mode: 1995-2020

Population growth will exacerbate trends in congestion and land use

competition, while creating an even larger internal market. The six-county

Southern California region will add more than five million people –

twice the population of Chicago – over the next 20 years.

Ultimately, additional freight growth will also be driven by demand

from this growing population.

Congestion - Highway and Facility Based

Congestion is a critical problem in Southern California. According

to the American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2001 Report Card for

America’s Infrastructure, Los Angeles highways create 82 person-hours

of delay per capita annually, the highest in the country. This report

also shows that Los Angeles has four of the 10 most congested highway

locations in the U.S. The I-405 at the I-10 interchange, U.S. 101

at the I-405 interchange, State Route 55 at the State Route 22

Interchange, and the I-10 at the I-5 interchange each average 10 minutes

of delay per vehicle per trip during peak hours. The contribution of

trucks to regional congestion is forecast to increase as truck vehicle

miles of travel (VMT) increase from 38 million miles in 2000 to 50 million

miles in 2010, according to estimates by the California Air Resources

Board (ARB), a higher rate of growth than is being experienced by automobile

traffic.

There remains a perception that trucks are significant contributors

to congestion due to their disproportionate use of roadway capacity,

but trucks are also influenced by congestion, and the resultant costs

eventually affect all consumers. Congestion leads to longer travel

times per trip, which in turn means that truck drivers will make fewer

pickups and deliveries during a day. Therefore, either the cost of

goods will increase or drivers’ income will decrease. Spreading

of the peak period exacerbates the congestion problem by making it more

difficult for truckers to squeeze their activities into narrowing windows

of low traffic volumes during off-peak hours.

Incident-based congestion creates unreliability in the transportation

system. Unreliable transportation systems cause travel times to become

unstable, preventing shippers, carriers, and logistics providers from

being able to precisely schedule shipments. This can cause a ripple

effect throughout the supply chain as inefficient inventory levels and

labor utilization increase the cost to deliver goods to the final customer.

Highway congestion also affects the operations of other transportation

facilities. Air cargo facilities rely on trucks to feed shipments to

the airport and to deliver goods to their final destination. Intermodal

rail facilities primarily utilize trucks to connect the rail system

to its customers and with other modes such as the ports. The largest

intermodal facility, the BNSF Hobart Yard in downtown Los Angeles, is

within 20 miles of four of the worst interchanges in the country (I-405

at I-10 interchange, U.S. 101 at I-405 interchange, State Route 55 at

State Route 22 interchange, and I-10 at I-5 interchange) [2].

I-710, the major access route to the Ports of Los Angeles/Long Beach,

experiences an average of five accidents, and the resultant delays,

everyday.

In addition to congestion on the highways, air, rail, and port facilities

in Southern California also face significant internal capacity constraints.

For example, airport and air traffic congestion is influencing the reliability

of airfreight operations. In 1999, the Federal Aviation Administration

reported that about 28 percent of departures (including freight and

passenger flights) at LAX were delayed because of air traffic volumes.

To accommodate future demand, the region must balance between expanding

the 6.1 million square feet of dedicated cargo space in the LAX

local area (over two million of which are on LAX property) and expanding

air cargo facilities at other local airports. The traffic volumes at

intermodal facilities serving both the ports and railyards in Southern

California are also projected to exceed capacity over the next 20 years.

Increased delays at terminals gates and within the terminals themselves,

coupled with increased passenger traffic demands to move freight into

and from these facilities, has led to additional concerns over the region's

ability to handle future freight movements.

Air Quality

Air quality management is another significant issue facing transportation

planners in Southern California. The region includes all or part of

seven different air quality non-attainment or maintenance areas in five

air basins. The South Coast Air Basin is a severe non-attainment area

and the need to demonstrate transportation plan conformity can constrain

capacity expansion.

Marine, rail, and truck modes predominantly use diesel fuels, which

are major sources of oxides of nitrogen (NOx – an ozone precursor)

and the primary mobile source of particulate matter. With the successes

of the past 30 years in the control of emissions from light-duty

on-road vehicles, emissions from freight modes are coming under increasing

scrutiny. However, the share of total mobile source NOx emissions in

the South Coast Air Basin attributable to trucks is expected to increase

from 44 percent to 53 percent between 2000 and 2010, even

with the adoption of new truck emission standards.

In California, trucks will face increasingly stringent emission standards

and requirements for cleaner burning diesel fuels. These requirements

will add costs to freight transportation. Historically, California

established its own emission and fuel standards, a difficult posture

given that many trucks operate in interstate commerce. Competitive

effects on the California trucking industry have long been an issue

of contention between the California Trucking Association and the California

Air Resources Board, which, with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA), regulates truck emissions and diesel fuel specifications. Regulation

of off-road mobile sources of pollution, including locomotive and steamship

emissions, have also periodically involved contentious relationships

among the carrier community, the California Air Resources Board, and

regional air quality management agencies.

Security

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001,

transportation security has become a priority. The Coast Guard has

dramatically stepped up its harbor patrols and monitoring efforts. The

California Highway Patrol completed a re-certification of the 1,000 companies

licensed to carry hazardous materials in the Southern California region,

although current inspection processes are costly and time consuming.

Containers must be selected (often at random), stopped, opened, sifted,

and approved to continue moving towards their final destination. Increasing

the amount of inspection introduces significant additional costs to

goods movement.

Air cargo facilities have a unique security issue, because passengers

and freight are often mixed aboard the same aircraft with cargo being

carried in the belly of commercial airlines. Screening of cargo is

likely to undergo increased scrutiny in line with the procedures that

have been enacted for air passengers and their baggage. Potential future

actions range from increasing the percentage of cargo security checks,

to improving the cargo screening equipment, to mandating that cargo

use dedicated air freighters only. The latter solution would dramatically

increase the cost for both air cargo and air passengers. In Southern

California, implementation of increased inspection processes will be

particularly difficult due to the high percentage of international freight

moving through airport facilities.

Safety

Provision of a safe transportation system is one of the key goals of

regional transportation planning in Southern California. However, the

interaction of passenger transportation and freight transportation on

the regional roadway system and at road-railroad crossings creates significant

safety concerns. Many accidents result from outdated highway designs

that do not reflect current vehicle size, vehicle performance, or driving

habits. The lack of proper median or narrow shoulders of highways has

also increased accident risk. Overloading or improper loading of vehicles

also creates safety concerns. Truck-involved accidents have a higher

incidence of fatality, property damage, and economic loss compared to

other types of accidents. Truck-involved accidents also generate traffic

congestion, because truck related incidents generally involve a larger

number of lanes blocked or closed. Records show that, in Southern California

during the five-year period from 1992 to 1997, there were over 27,000

truck-related accidents with 10,200 accidents involving injuries, 232

accidents involving fatalities, and over 20,000 accidents involving

property damage. Safety issues are more critical on the corridors with

heavy volumes of truck traffic. For example, in 2000, on a 27-mile

stretch of the I-710 Freeway, trucks were involved in over 31 percent

of its 2,250 reported accidents. The trucks were found to be at

fault in roughly half of the accidents.

Rail accidents are also a major concern in the region, especially at

rail-roadway crossings. Fatalities related to railroad traffic have

declined by two-thirds since 1960 as the result of improvements in rail

crossing technology, better education, and improvements to rail infrastructure.

Nevertheless, between 1997 and 2000, the California Highway Patrol counted

over 40 deaths and 345 injuries due to rail crossing accidents. Hundreds

of millions of dollars are spent in the region to separate the rail

and road infrastructure in an effort to reduce the safety risk of accidents

at highway-rail crossings.

Land Use

While the older metropolitan areas of the East and industrial Midwest

are grappling with freight access problems in mature, built-out, high-density

urban cores, Southern California faces its own unique land use-related

problems. The metropolitan area is famous for its sprawling development

and high-priced real estate. This development pattern has had significant

consequences for freight facilities in the region. Ports, airports,

intermodal terminals, and truck terminals frequently abut built-out

industrial, residential, and commercial areas, creating land-use conflicts

and limiting the ability to expand existing facilities. Attempts to

expand the LAX airport are fiercely opposed by residents in neighboring

communities, while residents of communities along the I-710 access routes

to the San Pedro Bay ports complain of environmental justice violations

associated with heavy truck traffic. Truck operators face increasing

parking and traffic route restrictions in cities throughout Southern

California.

Distribution centers utilize cheap suburban land to relocate and expand

their facilities. Housing developers are building in the same areas

to provide homes to the region’s growing population. Over time,

the pattern experienced in today’s developed sections of the metropolitan

area will be repeated. Community pressure will mount for the distribution

centers to relocate and expand further out of the region. One long-term

outcome may be more dispersed distribution centers and longer truck

trips, leading to an increase in local and regional congestion and emissions.

Regional Governance and Institutional Complexity

Transportation planning and programming in Southern California are

conducted in one of the most institutionally complex settings of any

region in the country. Figure 3.2 lists some of the many organizations

that are involved in regional transportation planning. Four different

district offices of the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans)

are responsible for planning, design, construction, maintenance, and

operation of the region’s state highways. SCAG, the regional

MPO, develops the Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) and provides funding

for numerous regional transportation studies. There are six county

transportation commissions/authorities (CTCs) that are responsible for

programming and funding the transportation projects in Southern California.

There are 14 subregions, represented by councils of government and subregional

planning agencies that work with SCAG and the CTCs to conduct transportation

planning throughout the region. At the base of this pyramid of regional

transportation agencies are 184 cities that have critical roles

in permitting roadway construction projects and operating and maintaining

much of the regional roadway network.

Figure 3.2 Organizations Involved in the Regional Transportation

Planning

There are a host of other governmental agencies involved in regional

transportation issues. These include the seaport and airport operators

(city agencies or joint powers authorities), the California ARB, and

the regional air quality management and water quality agencies. The

competing priorities, fragmented funding resources and authority, and

overlapping geographic jurisdiction of these different agencies make

cooperative planning a necessity and a frequent challenge. In general,

the various transportation agencies in Southern California have developed

processes for planning and implementing transportation programs and

projects that provide clear authority and jurisdiction to each participating

agency. However, most of these planning and implementation models encounter

problems when applied to freight projects. The reach of freight markets

and freight projects extends across traditional jurisdictional boundaries

and the cooperative relationships that are needed to deal with freight

projects (often involving both public and private agencies) have often

not been developed.

In an attempt to coordinate freight activities at the regional level,

SCAG has established a Goods Movement Advisory Committee (GMAC). While

the GMAC provides a useful forum for discussing freight issues that

have regional implications, it has yet to tackle some of the thornier

problems associated with institutional relationships. Some stakeholders

feel new institutional structures/models are needed to bring together

various agencies that have responsibilities for planning freight projects

that overlap existing jurisdictional boundaries. In the most widely

heralded freight success story in the region, the Alameda Corridor,

a new joint powers agency was created to handle implementation of the

project. Creating new joint powers agencies for every multi-jurisdictional

freight project in the region may prove cumbersome in the future. Which

agencies will be included in these agreements and which will not, could

be a source of much controversy. Clearly, Southern California is still

searching for the appropriate institutional mechanisms with which to

plan and coordinate major freight projects of regional significance.

4. Regional Successes in Freight

Despite the many challenges facing freight planners and managers in

Southern California, the region has achieved some notable successes.

Several projects have addressed freight transportation for both international

and domestic shipping needs through improvements at the international

gateways, the statewide and multi-state corridors, and within the metropolitan

roadway network and by dealing with many of the freight planning and

management issues mentioned in the previous section. Successes have

included capital projects, several of which are under construction and

many of which have been programmed. In addition, the region has developed

successful planning processes and institutional strategies, along with

innovative funding/resource management strategies. The lessons learned

from these successes and the remaining planning process, institutional,

and funding challenges should help inform discussion about future regional,

statewide, and national freight policy.

Successes at the International Gateways

Capital Project Successes

- The Alameda Corridor – Perhaps the nation’s

largest freight-oriented public works project, the Alameda Corridor,

consolidates harbor-related rail traffic from four separate branch

lines into a 20-mile, fully grade-separated route. The corridor connects

the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to the transcontinental rail

line near downtown Los Angeles, eliminating 200 at-grade crossings

and doubling rail speeds. The Alameda Corridor has helped the port

area cope with growth in international trade and roadway/railroad

congestion by facilitating more efficient on-dock rail movements to

and from the ports and reducing delays at rail grade crossings. Increased

on-dock rail will also have positive air quality implications as rail

movements emit fewer pollutants per ton-mile than do truck. The elimination

of 200 at-grade rail-roadway crossings will reduce accidents and improve

the safety of the freight transportation system.

- Port Infrastructure Improvements – All three

of the region’s deepwater ports are constructing major infrastructure

improvements on port property and at adjacent access roadways. These

include dredging and landfill projects, terminal expansion, and the

development of on-dock rail facilities, grade separations, interchange

construction, and bridge replacements. A major impetus for these

infrastructure improvements is to accommodate the projected tripling

of container traffic at the ports. Improvements to on-dock rail facilities

and roadway access improvements should also partially relieve congestion

near the ports. The on-dock rail improvements, coupled with the opening

of the Alameda Corridor, are projected to increase the on-dock rail

share of port inland container traffic from 15 to 35 percent.

- LAX/Ontario Air Cargo Improvements – These projects

include cargo terminal expansion and reconstruction, the development

of ITS for trucks at LAX, and roadway improvements related to the

opening of Ontario International Airport’s two new passenger

terminals in 1998. Like the terminal expansion and roadway access

projects at the ports, these improvements will help reduce congestion

in the vicinity of the airports and accommodate future growth in air

traffic.

Organizational and Planning Successes

- Port Truck Travel Demand Model – The Ports of

Long Beach and Los Angeles have developed a state-of-the-art truck

travel demand model that was used for the Port of Long Beach/Port

of Los Angeles Transportation Master Plan, and will be used as a major

component of the analysis tools for the I-710 Major Corridor Study.

This unique modeling tool is helping port and regional planners evaluate

alternatives that will address congestion and growth issues on access

routes to the port.

- West Coast Waterfront Coalition – The West Coast

Waterfront Coalition was formed to bring together shippers and other

interested parties on the waterfront to discuss ways of working together

to solve problems related to trade logistics operations in the ocean

shipping industries. By working together to change logistics practices

(such as changes in hours of operation), the group hopes to induce

more substantial changes in the operations of the port than if each

acted individually. Ultimately, increased efficiency in the supply

chain should translate into operational capacity improvements to deal

with growth and congestion problems.

- National Center for Metropolitan Research (METRANS)/Center for

International Trade and Transportation (CITT) – A major

program that has brought public and private interests together in

the region is METRANS, a University Transportation Center funded by

the U.S. DOT and operated by the University of Southern California

and the California State University at Long Beach. CITT, also at

the California State University at Long Beach, is another organization

that has focused on research and education efforts related to the

unique needs at the gateway facilities. CITT has been instrumental

in bringing together public and private stakeholders on issues related

to trade and transportation, including hosting the Southern California

Goods Movement Summit, and offers degree and certificate programs

in global logistics. METRANS/CITT have also facilitated dialogue

among industry and labor stakeholders in international trade through

their “town hall” meetings. These stakeholder meetings

cover a wide range of topics that are helping address operational

improvements that involve all of the stakeholder groups.

Funding/Resources Successes

- Financing for the Alameda Corridor – The approach

used to generate the required funding to construct the Alameda Corridor

is an outstanding example of how a combination of local grant money,

federal loan money, and user fee backed revenue bond financing can

be used to raise the significant capital required to make gateway

improvement projects work. The largest portion of funding ($1.16

billion) was obtained from revenue bonds. Another $400 million was

provided through federal loans under the TIFIA program. This debt

financing will be repaid with revenues obtained from user fees. The

Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority (ACTA) came up with a plan

to charge a $30 fee on all containers using the corridor. The remainder

of the project’s funding came from port contributions ($394

million), local contributions (conventional funding sources from the

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LACMTA)),

and other local sources ($130 million).

- ITS Intermodal Demonstration Funds – The ports

have also been successful in obtaining a grant from the Federal ITS

Intermodal Program, which was created to demonstrate how ITS solutions

could be applied to major intermodal hubs. The ports are using this

funding to implement a comprehensive ITS program that will link real-time

traffic information at the terminal gates with public ITS in the vicinity

of the port and private information management systems in order to

allow for more efficient scheduling, dispatching, and traffic management.

Successes on State and Multi-State corridors

Capital Project Successes

- The Alameda Corridor East (ACE) – The goal of

the ACE project seeks to mitigate the effects of increased rail traffic

along a freight mainline corridor from Los Angeles through San Bernardino

County. The project will include safety upgrades, traffic signal

control measures, constructing grade separations at rail crossings,

and the elimination of at-grade rail crossings. In addition to the

safety improvements, these projects will allow for more efficient

rail operations to deal with growth in domestic and international

trade by rail.

- The Orange County Gateway (Orangethorpe Corridor) –

This project will provide grade-separation for the BNSF mainline

through northern Orange County. The Orange County Gateway is part

of the larger ACE program and addresses rail-highway safety issues

and the need for more efficient, higher speed rail operations through

this congested rail corridor.

- San Bernardino County Infrastructure Projects – Using

traditional state and federal transportation funds in combination

with $600 million from a half-cent, voter-approved sales tax, this

subregion made numerous improvements integral to movement of freight

in and through San Bernardino County. Some of the key projects to

improve interregional goods movement facilities have included additional

capacity on SR-60 (a critical truck route through the county), upgrades

to I-215 that improve access to San Bernardino International Airport

and the BNSF Intermodal Facility, and ground access improvements at

Ontario International Airport.

- Railroad Investment Programs – After the mid-1990s

mergers left the Western U.S. with two Class I railroads, both rail

companies made major investments in Southern California. For example,

the BNSF has invested in new track and parking at its East Los Angeles

intermodal facility and upgrades and major expansion of the San Bernardino

intermodal facility. These improvements will expand capacity and

reduce rail congestion throughout the region.

Organizational and Planning Successes

- Development of Regional Freight Planning Capacity –

The Caltrans Office of Goods Movement has funded full and partial

positions in many of the Caltrans district offices for goods movement

planners. Through this process, local Caltrans officials are being

trained to understand the unique requirements of freight projects;

and this increases the likelihood that freight concerns will be addressed

in projects that involve the state highway system. This should also

help address some of the institutional obstacles to getting freight

projects programmed.

- Development of Statewide and Interregional Commodity Flow Data –

Recognizing the need for improved data and analytical tools, public

agencies in Southern California have worked together to develop several

innovative programs. California was one of the pilot states to develop

an intermodal management system (ITMS) as required by the Intermodal

Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA). The state

continues to support the ITMS even though the requirement for this

system has been eliminated from the federal regulations. The freight

component of ITMS includes county-level commodity flow data for the

entire state. Building from this early program, SCAG conducted an

interregional goods movement study in the mid-1990s that further developed

regional commodity flow data. These data are used in a variety of

planning studies to help understand the transportation requirements

to facilitate freight growth in the region.

- I-10 Pooled Funds Study – Caltrans has been a

leader in bringing together a group of state Department of Transportations

(DOTs) along the I-10 corridor from California to Florida to look

at how coordinated multi-state and multimodal freight planning can

be conducted for a nationally significant freight corridor. A pooled

funds study is being conducted to characterize current and projected

freight flows and to develop alternatives for improved freight efficiency

and safety in the corridor.

Successes on the Metropolitan Transportation Network

Capital Project Successes

- Los Angeles City Goods Movement Improvement Program –

This program was one of the first local goods movement investment

programs developed with funding assistance from SCAG. In Phase I

of the program, the City obtained $1.8 million in discretionary

funding from the LACMTA Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) to

address problems with truck movement and access to intermodal facilities,

distribution centers, industrial uses, and freeways in the City, as

well as truck conflicts with sensitive land uses.

- Riverside County Infrastructure Projects – Riverside

County also has a half-cent sales tax that has been used to fund major

transportation projects that have benefited goods movement. Currently,

the Riverside CTC has several major goods movement-related projects

underway, including construction of truck climbing lanes and truck

bypasses and interchanges on key freight routes. One interesting

example of public-private partnership in the county was the establishment

of the Metrolink commuter rail service, which invested millions of

dollars in track improvements on main lines of the Class I freight

railroads.

Organizational and Planning Successes

- Freight Element in SCAG Long-Range Transportation Plan –

When the ISTEA mandated that states and Metropolitan Planning Organizations

(MPOs) plan for efficient intermodal systems for passenger and freight

transportation, very few regions had instituted the necessary processes

to examine goods movement needs. However, in the Southern California

region, a number of steps have been taken to develop the necessary

planning processes. Almost immediately after the passage of ISTEA,

SCAG began implementing a goods movement planning program, including

the designation of goods movement planners on the staff and development

of a freight element in the RTP.

A major freight focus in the most recent RTP has been the identification

of a system of corridors that could benefit from dedicated truck lanes.

SCAG, in partnership with Caltrans District Offices and the relevant

CTCs, is undertaking a process to examine the feasibility of the truck

lane concept in these corridors. To assist in this process, SCAG

has developed a Truck Lane Task Force. SCAG is also conducting studies

of rail capacity constraints in order to develop regional public-private

investment strategies. All of these planning efforts have addressed

regional governance and multi-jurisdictional cooperation in the region.

- Subregional Freight Studies – Another successful

program initiated by SCAG is the funding of subregional freight studies.

These studies, which often focus on arterial needs and involve city

public works directors in the process, have helped participating cities

identify projects for programming in the TIP. These projects have

been very successful in developing multi-jurisdictional collaboration

within the region and, in a number of cases, have helped facilitate

public-private cooperation by focusing on specific projects of concern

to the goods movement industry.

- Regional GMAC – Several efforts have been undertaken

in Southern California to facilitate public-private collaboration

on freight projects. SCAG convened a regional GMAC that brings elected

officials and public agency staff together with representatives of

private sector freight interests to address problems of regional significance.

- Regional Heavy-Duty Truck Model –In the late-1990s,

SCAG undertook development of a regional heavy-duty truck model.

Funding for this project was obtained from discretionary funds of

the South Coast Air Quality Management District, which was interested

in obtaining more reliable forecasts of truck activity for emissions

modeling.

- Subregional Truck Models – A number of subregions

have also developed truck models or truck elements of subregional

travel demand models, including the San Bernardino Associated Governments

(SANBAG) and Imperial County. The LACMTA has recently begun a major

effort to build a county truck model and freight database that will

be used in the evaluation and planning of future freight projects.

- Truck Data Collection Programs – There have been

a number of efforts undertaken in the region to collect data on truck

activity. These include the regular Caltrans truck count program

on state highways, the recent Caltrans Statewide Truck Travel Survey,

numerous truck counts and shipper surveys conducted during the subregional

goods movement studies, a major truck count and truck origin-destination

study currently underway at SCAG, and planned truck travel diary surveys

to be conducted by the LACMTA.

- Freight Partnership Working Group – Recently,

the LACMTA kicked off a major effort to enhance its freight planning

capabilities and convened a Freight Partnership Working Group to assist

in this effort. The Working Group, which includes public and private

sector freight interests, is assisting the LACMTA in establishing

policy and programming priorities and will help with data collection

needed to further develop models and analytical tools.

Funding/Resources Successes

- Programming Funds in Traditional TIP Process –

All of the CTCs in the region have begun to program local roadway

and arterial projects through their traditional TIP process. By focusing

planning resources on identification of fixable problems and educating

decision-makers about congestion relief, safety, and air quality benefits

of projects, the programming of freight projects is beginning to occur.

As a number of the region’s planners have noted, it helps when

freight projects also benefit non-freight modes.

- Local Sales Tax Measures – Several CTCs have been

able to program projects with funds from local sales tax measures.

In these cases, projects with clear local benefits have been the leading

candidates. For example, projects in San Bernardino County and Riverside

County that used local sales tax revenues to fund improvements on

freeways and freeway interchanges that are also major commute routes

or to provide better access to Ontario Airport, which serves a growing

volume of passenger travel, were sold to the public without any significant

discussion of freight benefits.

5. Lessons Learned and Continuing Challenges

Much can be learned from the Southern California experience that is

relevant to the national freight policy discussion. The region’s

project successes provide examples of the full range of types of freight

projects that states and MPOs may need to undertake at international

gateways, state and multi-state corridors, and in the metropolitan road

network. There are many more project ideas that have been identified

and will be pursued in the future.

What is most relevant to national freight policy are the lessons learned

and challenges in the areas of funding/financing and planning processes/institutional

relations. Within each of these broad areas, there are a number of

specific issues that have emerged in Southern California that are discussed

in the remainder of this section

Funding/Financing

Adequacy of Funding Resources

With the enormous growth in goods movement traffic predicted for Southern

California across all modes, it is not difficult to see why there is

a need for substantial investment in infrastructure and operational

improvements. However, the cost of maintaining and improving the existing

transportation network within the region for all users exceeds the available

resources. The 2001 SCAG RTP estimates costs of all regional transportation

projects over the next 20 years at $44 billion, compared with available

resources estimated at only $24 billion. In addition to the enormous

construction costs associated with these projects, transportation projects

in Southern California, as elsewhere in the country, face growing costs

of right-of-way acquisition, environmental compliance, complex public

involvement processes, and other planning costs that will strain local

transportation budgets. Competition for transportation funds will continue

to be hard fought and will challenge the political ability of the region’s

decision-makers.

Several freight projects have been identified that have the potential

to improve the flow of goods in the metropolitan area. However, freight

projects tend to be expensive, due to their scale and institutional

complexity, and funding of the projects remains a challenge in a fiscally

constrained environment.

A major program that may suffer from funding limitations is the development

of dedicated truck lanes. [3] The SCAG RTP has identified five freeway

segments that would benefit from the use of truck lanes. However, a

recent feasibility study of truck lanes on the SR-60 freeway indicated

that, even if tolls were optimally applied to the truck lanes, less

than 30 percent of the project costs could be recovered from project

revenues. Therefore, billions of dollars of the truck lane projects

would have to be funded from other (likely public) sources.

Table 5.1 SCAG RTP Freight Projects

| Truck Lane Projects |

Truck Climbing Lane Projects |

Truck Lane Study Projects |

| SR-60 (I-710 to San Bernardino County) |

SR-57 (Lambert to Tonner) |

I-5 (I-605 to SR-14) |

| SR-60 (San Bernardino County to I-15) |

I0-15 (Devore to Summit) |

I-5 (SR-14 to SR-126) |

| SR-60 (Los Angeles County to Riverside

County) |

- |

I-710 (SR-60 to Port of Long Beach) |

| I-15 (SR-60 to San Bernardino County) |

- |

- |

| I-15 (Riverside County to U.S. 395) |

- |

- |

Other projects, such as the Orangethorpe Corridor project and the San

Bernardino and Riverside County portions of the ACE project, have substantial

funding needs that have not been fully met.

As long as freight projects must compete in such a highly constrained

fiscal environment, they will advance slowly. This may be especially

true for projects at international gateways and on multi-state networks.

These freight projects tend to be especially costly and are often perceived

locally as having state or national benefits that should be paid for

by the state and federal governments. In addition, lack of flexibility

in many of the available funding sources that are targeted for highway

and transit improvements further limits the funding available for these

types of projects.

Burden Sharing and Fairness: The Distribution of Costs and Benefits

of Freight Projects

Projects conveying national benefits but having local repercussions

create unique challenges for local funding. For example, over $3 billion

worth of road improvements have been proposed for I-710, the major access

route to the San Pedro Bay ports. These improvements would have national

transportation implications, since a great deal of the truck traffic

is to support international trade that does not directly benefit Southern

California. Generating local sources of funding for these projects

is often difficult due to the perception that the projects benefit national

interests and have a mixed effect on local traffic. Other projects,

such as the Alameda Corridor, are completed only at substantial additional

cost in terms of the mitigation needed to overcome local opposition.

The issue of equitable distribution of costs and benefits for goods

movement projects is a question that is hotly debated in Southern California.

Many of the most expensive freight projects in the region involve access

improvements to international trade hubs and dealing with increasing

volumes of through traffic on facilities that serve these hubs. Projects

such as ACE, the Orangethorpe Corridor, and the San Bernardino and Riverside

County grade separation projects are all dealing with increased delay

and safety problems at railroad grade crossings due in part to increased

international trade traffic. The amount of local funding that has been

obtained for these projects to-date falls far short of need and many

local decision-makers contend that with national benefits should come

national funding.

In the past, there has been limited political support at the federal

level for separate categories of funds for nationally significant freight

projects, so funding from Washington has often come through earmarking

(as it did in the case of the Alameda Corridor). This often pits the

freight interests of this region against each other across jurisdictional

lines. At the state level, the source of funding for improvements

suggested for the Global Gateways Development Program has yet to be

identified and could involve contentious debate over user fees and state/local

allocation of transportation discretionary funds.

The Importance of Local Benefits in Justifying Local Funding

The evidence in Southern California suggests that, while economic development

benefits are often associated with successful freight projects, this

seems to be more important to attract federal funding than local funding.

Former Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority (ACTA) staff indicate

that it was the congestion relief and air quality benefits of the Corridor

that attracted local funding. This local funding, even in the case

of a nationally significant project like the Alameda Corridor, was extremely

important. The LACMTA provided $347 million in direct grants,

or 14 percent of the total project funding, based on the local congestion

and air quality benefits that could be demonstrated. In Los Angeles

City, while economic development benefits were an initial rationale

for the Goods Movement Improvement Program (when the project was started,

California was at the height of the recession of the early 1990s), ultimately

the project was sold on the merits of its safety benefits.

Innovative Financing and User Fees

Many goods movement planners in the region acknowledge that it will

be necessary in the future to come up with alternative revenue sources.

Thus, there is increasing interest in user fees. One of the successful

features of the Alameda Corridor was the provision for a $30 container

fee on all cargo moving in the Corridor. This provided a revenue stream,

which when combined with attractive loan terms from the federal government,

allowed for almost two-thirds of the financing of the project to come

from debt instruments. But not all freight projects can be structured

with user fees. Projects on Southern California’s freeways will

clearly address congestion, air quality, and safety issues that affect

all motorists and many non-motoring residents. Again, the issue of

equitable distribution of costs and benefits and linking revenue sources

with use of the facility is important in evaluating user fee alternatives.

There is also local concern about the negative effects that user fees

could have on the competitive position of the region in both international

and domestic trade. Local state legislators have recently proposed

to collect some form of fees on all cargoes moving through the ports

and to use this to finance landside access improvements. There are

strong and mixed feelings about this proposal among the private and

public sector freight interests.

Some local decision-makers think that the answer to the funding problem

may lie, at least in part, with an alternative mechanism for distributing

revenues from fees already collected by the federal government in connection

with trade activities. These officials argue that more funds ought

to be available locally from customs fees and the Harbor Maintenance

Tax to pay for improvements necessary to support efficient trade transportation.

Public Investment in the Private Freight System

A particular funding issue for freight projects in Southern California

is the need for funding to assist the private sector for projects with

broad public sector benefits. The private sector often perceives these

projects as having an insufficient return on capital due to long payback

times, lack of equity, and high risk. This is becoming an increasingly

important issue in the region as public agencies become more interested

in rail capacity problems. Improvements to the regional rail system

could create opportunities to divert more truck traffic off of congested

freeways, as well as reducing delay at grade crossings. Making these

investments with public funds is difficult. In Southern California,

successful financial participation by public agencies in railroad projects

has generally come in connection with commuter rail projects (such as

the Metrolink project in Riverside County), safety upgrades, or land

swaps.

Institutional/Planning Process

Regional Coordination and Decision-Making

A major problem faced by freight projects in Southern California is

the large number of agencies with overlapping geographic jurisdiction

that become involved in significant goods movement projects. Freight

markets do not respect political boundaries, and this requires agencies

to cooperate not only in the implementation of projects, but also in

the identification of needs and solutions.

The Problem of Coordinating Freight Projects that Cross Political

Boundaries

An example of how this problem has been played out in Southern California

comes from the history of the Alameda Corridor. The ACTA was formed

as a joint powers agreement between the cities of Los Angeles and Long

Beach (both San Pedro Bay ports are managed by the departments of their

respective cities). Since the Alameda Corridor runs through a number

of smaller cities on its way from the ports to downtown Los Angeles,

these smaller cities were originally invited to participate as members

of the board of the ACTA. Distrust between the cities and the ports

concerning how project funds would be spent and the ports’ concern

about their fiduciary responsibility for the bonds that were to be issued

eventually led to a reconstitution of the ACTA board that eliminated

the smaller cities.

After lawsuits between the cities and the ports were resolved, the

ACTA and the cities ultimately came to agreements codified in two separate

memoranda of understanding that provided $12 million in mitigation

funds to the cities and a guarantee of expedited permitting for construction

to the ACTA. The road to this collaboration was expensive and time

consuming.

Boundaries Don't Match Freight Movement Patterns

Many other freight projects in the region involve the movement of goods

over transportation networks that cross jurisdictional lines and similar

issues of collaborative planning are faced consistently. Defining the

appropriate boundaries of goods movement projects can create problems

from the outset. While it may be convenient to define a goods movement

project consistent with the boundaries of existing subregional or political

boundaries, this may run counter to the need to produce the most cost-effective

system-level solutions to problems. For example, the definition of

the ACE project now carries a particular political significance, because

it is a designated corridor eligible for funding under the National