Planning for Transportation Systems Management and Operations within Subareas – A Desk ReferenceCHAPTER 2. PLANNING FOR TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS MANAGEMENT AND OPERATIONS WITHIN SUBAREASWHY IS PLANNING FOR TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS MANAGEMENT AND OPERATIONS WITHIN SUBAREAS NEEDED?The benefits of transportation systems management and operations (TSMO) within subareas are achieved through coordinated, strategic implementation and ongoing support through day-to- day operations and maintenance, and this requires planning. All TSMO strategies require some investment of resources, which could be in the form of funding, data, equipment, technology, or staff time. To obtain these resources and then make the best use of them, planning is needed. If TSMO is to be implemented effectively within subareas, there are a number of planning activities that should occur prior to implementation, including:

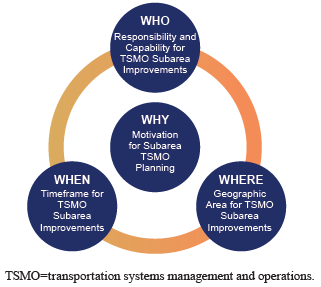

Traditionally, transportation planning and TSMO have been largely independent activities. Planners typically focus on long-range transportation plans (LRTPs) and project programming. Operators are primarily concerned with addressing immediate system needs (e.g., incident response, traffic control, and work zone management). Planning for TSMO connects these two vital components of transportation, bringing operational needs and solutions to the planning processes and likewise bringing longer term, strategic thinking to operations managers. The following examples demonstrate the need for planning for TSMO within subareas. The examples are a small set of commonly missing opportunities for improving the operational performance of the subarea transportation network through TSMO planning. Incorporating Transportation Systems Management and Operations as a Consideration into Subarea Planning Processes Led by Planning GroupsWhen planning groups develop subarea plans, the TSMO perspective often is absent. This may occur because planners lack familiarity and experience with operations strategies. TSMO activities generally occur outside of the plan, design, and build functions for capital infrastructure investment. Often, TSMO is afforded a place alongside system maintenance activities in agency organizational charts, relegating TSMO activities to what happens after the planning, design, and build out is complete. As a result, agencies miss the opportunity to integrate TSMO with the tools and benefits that can help address community needs and achieve community goals. By incorporating TSMO planning practices and strategies into the goal setting, existing conditions assessment, alternatives development and analysis, and project selection stages, final projects will have a balanced plan featuring both operational and infrastructure investments that make them more financially feasible and achievable in the near term. Linking Subarea Network Optimization Efforts Led by Operations Groups with the Overarching Policy Framework and Plans of Their AgencyCoordination activities and integration with long-range planning efforts are often overlooked when advancing transportation operations projects. For example, a regional traffic operations group initiates a process to provide real-time parking information in a central business district (CBD). Their vision is to install several variable message signs at key portals into the CBD to transmit data on parking availability. By coordinating during the overarching planning process, the traffic operations group can align the operational benefits with the broader goals identified in LRTPs to draw champions at the local and regional levels, who will in turn open doors to funding and other resources, including integration with other projects. Using the Systems Engineering Process to Plan for Intelligent Transportation System or Transportation Systems Management and Operations DeploymentsThe use of the systems engineering process to support the implementation of intelligent transportation system (ITS) or TSMO deployments in a subarea is occasionally overlooked. As an illustrative example, agency planners forecast 50 percent traffic volume growth in a subarea within 10 years. In response, the traffic operations group decides to install adaptive signal control technology. The agency procures equipment and software without completing a systems engineering process. Implementation falters with the discovery that the selected solution fails to meet key needs. Benjamin Franklin wrote, "If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail!" This holds particularly true for complex technology solutions like ITS. When agencies use good planning practices, like systems engineering, to clarify needs, goals, and requirements, they minimize the risk of failure. Failed projects, especially when highlighted by the media, make it harder to secure funding and to achieve buy-in from the public and key decision-makers for future projects. PLANNING CONTEXTS FOR TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS MANAGEMENT AND OPERATIONS WITHIN SUBAREASAdvancing Transportation Systems Management and Operations within Several Planning ContextsBefore focusing specifically on planning contexts for subarea TSMO planning, it is important to understand the larger context for TSMO planning, which may involve statewide, district, metropolitan, corridor, or local or subarea planning. At the statewide level, planning for TSMO takes many forms. Planning for how TSMO will be conducted may be incorporated broadly in the State's long-range transportation plan, which is developed by the State DOT in collaboration with the State's MPOs and other transportation stakeholders. The State's long-range transportation plan may contain TSMO elements that are part of a larger multi-state initiative that individual States agree to support (e.g., a multi-state road-weather information system or traveler information system). TSMO planning also may be performed at the district level or across a state, where each State DOT district develops its own strategic operations plan in coordination with MPOs and local agencies within each DOT district. Alternatively, TSMO planning may occur at the corridor level, across the state, especially where a State has identified priority corridors where there are specific needs (e.g., improved goods movement from a seaport; more efficient commuter options to and from major employment areas; or better access to major entertainment, recreational, or sports venues). The 2012 surface transportation authorization act, Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century, requires that "[t]he statewide transportation plan and the transportation improvement program developed for each State shall provide for the development and integrated management and operation of transportation systems and facilities…"22 States are encouraged to include TSMO in their long-range transportation plans developed through performance-based planning.23 For more information on planning for TSMO at the Statewide level, readers should consult the Federal Highway Administration's (FHWA's) Statewide Opportunities for Integrating Operations, Safety and Multimodal Planning: A Reference Manual.24 At the metropolitan level, planning for TSMO often is led or facilitated by the MPO, which convenes a group of TSMO stakeholders, typically including State DOT district or regional offices, to advance TSMO in the region. Metropolitan planning for operations is frequently conducted in coordination with the development of the metropolitan transportation plan as a means of including TSMO priorities and strategies into the overall plan and including TSMO program and projects in the transportation improvement program (TIP). FHWA recommends that planning for TSMO at the metropolitan (as well as statewide) level be driven by outcomes- oriented objectives and performance measures. Rather than focusing on projects and investment plans, the planning-for-operations approach first emphasizes developing objectives for transportation system performance and then using performance measures and targets as a basis for identifying solutions and developing investment strategies. This is called the "objectivesdriven, performance-based approach." FHWA provides more information on using this approach to integrate TSMO into the metropolitan transportation planning process in a key document: Advancing Metropolitan Planning for Operations: The Building Blocks of a Model Transportation Plan Incorporating Operations - A Desk Reference.25 Corridor planning focuses on planning for a linear system of multi-modal facilities in which an existing roadway or transit facility will typically serve as the "backbone" of the corridor. The travel-shed helps determine the length and breadth of a corridor area, which usually connects major activity centers or logical destinations. Corridors can range in length from a few miles in an urban location to hundreds of miles for State or multi-State corridors. In addition to different spatial scales, corridors also may have different modal foci (e.g., freight rail corridor, high capacity passenger rail corridor, limited-access highway corridor, or bus rapid transit corridor). Usually, corridor planning focuses on a combination of modes and a network of facilities. Local or subarea planning refers to planning which addresses "A defined portion of a region (such as a county) in more detail than area-wide or regional plans. Subarea studies are similar to corridor studies, with the distinction that a subarea study generally addresses more of the total planning context and the broader transportation network for the area."26 Because subarea planning addresses a fairly broad planning context, this often involves a larger number of potentially affected stakeholders and comprehensive visioning for the area. Local studies may address a municipality (city or county) or other area, and may include a wide array of different issues, including transportation (motorized and non-motorized mobility), land use, and urban design. Corridor planning for TSMO also occurs at the local level (e.g., when one or more local agencies want to address mobility issues on an individual corridor within the local jurisdiction). Statewide and metropolitan long-range transportation plans establish the policy framework for corridor, local, and subarea planning and provide guidance in terms of regional and statewide priorities related to goals, objectives, strategies, and transportation investments. MPOs, counties, and cities commonly lead local and subarea planning efforts. On the other hand, corridor studies and planning activities are often performed by State DOTs and MPOs. Statewide and regional TSMO or ITS plans and associated architectures are a resource that can inform corridor, local, and subarea planning activities. These plans typically include existing and planned TSMO strategies that have been identified for statewide or metropolitan area use. Some include suggested TSMO strategies or implementation projects for specific subareas or an entire toolbox of potential strategies to consider. The Who, Why, When, and Where of Transportation Systems Management and Operations Planning within a SubareaThe context for TSMO planning at the subarea level provides answers to the basic questions of why, who, where, and when (Figure 2).  Figure 2. Diagram. Context for transportation systems management and operations planning within subareas. Motivation for Transportation Systems Management and Operations Within Subareas (Why)? The answer to why provides the primary motivation for considering TSMO strategies within the subarea. The motivation can be the result of the broader planning process where a specific subarea is identified as an area requiring significant improvements or corrections (as in Example Context 1), or it could come through a coalition of local and regional partners that identifies a particular subarea as critical to mobility and economic activity throughout a larger area. For example, central business districts (CBD) may develop pedestrian malls, off- street parking, bicycle sharing, and other amenities to attract businesses, employers, tourists, and consumers to that area as a means of stimulating economic activity. The need for subarea improvements also could come from within operating agencies that see opportunities for providing a higher level of service (LOS) to travelers in the subarea (e.g., through more accurate and timely traveler information, better synchronized signals, or improved incident management in the subarea). The example provided in Context 1 illustrates how frequent incidents in roadways that travel into and through CBDs require a range of stakeholders because of the potential effects of improvements on businesses, nearby neighborhoods, transit services, pedestrians, bicyclists, and others. Investments required to implement improvements may be integrated into regional transportation plans and may provide the motivation for implementing TSMO strategies and tactics in a subarea. The why also might be the result of growing concerns about congestion, safety, air quality, reliability, or other recurring problems within a subarea, or in search of ways to stimulate economic activity within the subarea, which may or may not be addressed in regional transportation plans. The motivation also might come as a result of a desire to improve the livability of a subarea within a larger region (see Example Context 2). Interest in TSMO strategies in a subarea also might arise in conjunction with new development projects when integrating TSMO strategies and tactics can be most cost effective (see Example Context 3). Example Context 1: TSMO applications within the subarea are outside the regional planning process, such as incident management on roadways in the central business district.

Example Context 2: Supports subarea planning.

Who? The who for TSMO planning for subareas establishes responsibility for planning and implementing TSMO strategies within a subarea that may span multiple jurisdictions (e.g., city and county) and requires interagency and multi-jurisdictional agreements regarding responsibilities for planning, designing, implementing, operating, monitoring, and maintaining TSMO strategies and tactics. This could be an authority acting on behalf of multiple entities (e.g., a toll authority or regional transit authority) or a single entity designated as the lead agency on behalf of other jurisdictions or agencies. Alternatively, if the subarea of interest is within a single jurisdiction, responsibility may lie with a single agency within the jurisdiction, but, even in this case, there are likely to be other agencies and jurisdictions that are affected by decisions made with respect to the subarea of interest, thus communication and coordination with these agencies and jurisdictions is important to the success of the TSMO improvements in the subarea. Example Context 3: A study does not include transportation systems management and operations (TSMO) as initial focus, such as developing bicycle routes, off-street parking, or a pedestrian mall.

The who in TSMO planning for subareas reflects the capacity and experience of the responsible agency or agencies. Agencies with considerable experience in TSMO planning will have the tools needed to evaluate various TSMO strategies and will understand the data available to evaluate these strategies. Agencies with less institutional knowledge and experience with TSMO strategies and tactics can draw on external expertise to assist in integrating TSMO into subarea planning. Moreover, those with less experience may find institutional resistance to considering and committing resources to TSMO improvements and may need to enlist the support of champions who can help make the case for TSMO as a means for improving transportation system performance within the subarea, particularly as it relates to other subarea priorities (e.g., economic development, livability). In some cases, a regional entity, such as an MPO or the major jurisdiction (e.g., city, county, or parish), will serve as the lead or facilitating entity for convening multiple agencies and jurisdictions to develop operations objectives for the subarea under consideration, especially if the subarea improvements have implications beyond the subarea (e.g., restrictions on vehicle access, changes in parking availability). State DOT district or regional offices also may be involved because, in some States, the State DOT is responsible for maintenance and operations of signal systems within local jurisdictions. Other local and State agencies, such as law enforcement, also may be engaged, because they are often the entities most visible to the traveling public and will have significant responsibility for implementing and enforcing new operations strategies. Where? The where of TSMO planning for subareas is critical both to identifying key entities responsible for planning and implementing TSMO strategies and tactics and to determining who will benefit or be otherwise affected by TSMO strategies and tactics considered for the subarea. For example, improving signal synchronization in a CBD will improve mobility for travelers who wish to move through an area quickly; on the other hand, local business along the route may perceive (rightly or wrongly) that they are less accessible due to higher average speeds, pedestrians may feel that they are at greater risk because of traffic flows, and adjacent neighborhoods may perceive (again, rightly or wrongly) that they are given lower priority (seen as longer cycle times for the primary roadway). Subareas of interest are often within major population centers, and both mobility and accessibility are critical to the well-being of the people, the quality of services (e.g., schools and hospitals), and the success of businesses within the subarea. Mobility and accessibility involve moving goods and people into, within, and through the subarea and the adjacent, broader region. The examples provided in the next section illustrate the variety of geographic boundaries that may fall within a subarea, depending on the issues that drive decisions regarding investments in TSMO strategies. When? The when of TSMO subarea planning considers both the point at which TSMO planning takes place and the timeframe for TSMO strategies and tactics. TSMO subarea planning is most effective when integrated into the planning process for a new facility, when an existing facility is expanded or undergoing major renovation, or when other major investments are being made within the subarea (e.g., major utility improvements that require affect mobility during installation, major commercial developments that will affect future traffic demand and flows). At that time, plans for TSMO projects that require the installation of technology (e.g., cameras, fiber optics, transit priority options, and dynamic message signs) or roadway features (e.g., turn lanes and dedicated lanes) can be included in the design most effectively. However, in many cases, TSMO strategies are considered only when issues arise that require attention to transportation operations or highlight the need for new services (e.g., transit routes and schedules, parking management). In addition to when the TSMO subarea plans are developed and implemented, the TSMO planning process considers the timeframe for implementation and operation of the TSMO investments. TSMO investments typically have short returns-on-investment (ROI) relative to other investments in transportation infrastructure and so can be justified based on much shorter life cycles than can major capacity expansion projects. Further, in subareas, transportation system performance may not be the only—or even the most important—aspect of investments in TSMO. For example, a smartphone app that points vehicle operators to available parking may be primarily designed to encourage visits to a commercial district rather than expedite vehicle movements. On the other hand, TSMO investments tend to be technology intensive and, with relatively rapidly changing technology, investments in these strategies should be made with an eye toward next-generation technologies and capabilities. As more advanced technologies emerge in sensors, vehicles, communications, visualization, etc., TSMO subarea planning should consider how current TSMO investments will accommodate future upgrades and new capabilities that may make past investments less attractive. For example, growth in shared mobility services (e.g., Zipcar™ or Uber™) may lead to integrating accommodations for and real-time information about these shared service into subarea TSMO plans. EXAMPLES OF CURRENT PRACTICESBelow are brief examples of current practices for TSMO planning at the subarea level. These help to illustrate the wide breadth of activities that are considered to be planning for TSMO within subareas.

22 Title 23 United States Code Section 135(a). [ Return to note 22. ] 23 Federal Highway Administration, Model Long-Range Transportation Plans: A Guide for Incorporating Performance-Based Planning, FHWA-HEP-14-046 (Washington, DC: August 2014). Available at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/performance_based_planning/mlrtp_guidebook/. [ Return to note 23. ] 24 Federal Highway Administration, Statewide Opportunities for Integrating Operations, Safety and Multimodal Planning: A Reference Manual, FHWA-HOP-10-028 (Washington, DC: June 2010).Available at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/processes/statewide/practices/manual/index.cfm. [ Return to note 24. ] 25 Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, Advancing Metropolitan Planning for Operations: The Building Blocks of a Model Transportation Plan Incorporating Operations - A Desk Reference, FHWA-HOP-10-027 (Washington, DC: 2010). Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop10027/. [ Return to note 25. ] 26 Federal Highway Administration, Guidance on Using Corridor and Subarea Planning to Inform NEPA (Washington, DC: April 2011). Available at: http://environment.fhwa.dot.gov/integ/corridor_nepa_guidance.asp#toc212. [ Return to note 26. ] 27 Metro, Portland, Oregon, East Metro Connections Plan, June 2012. Available at: http://www.oregonmetro.gov/east-metro-connections-plan. [ Return to note 27. ] 28 City of Salt Lake City, Downtown in Motion: Salt Lake City Downtown Transportation Master Plan, November 6, 2008. Available at: http://www.slcgov.com/transportation/transportation-downtown-motion-salt-lake-city-downtown-transportation-master-plan. [ Return to note 28. ] 29 New York City Department of Transportation, NYC DOT Announces Expansion of Midtown Congestion Management System, Receives National Transportation Award, June 5, 2012. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/pr2012/pr12_25.shtml. [ Return to note 29. ] 30 New York City Department of Transportation, Sustainable Streets: Strategic Plan for the New York City Department of Transportation 2008 and Beyond, 2008. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/about/stratplan.shtml [ Return to note 30. ] 31 Atlanta Regional Commission, Strategic Regional Thoroughfare Plan, January 2012. Available at: http://www.atlantaregional.com/transportation/roads--highways/strategic-regional-thoroughfare-plan. [ Return to note 31. ] 32 Puget Sound Regional Council, Congestion Management Process, 2010. Available at: http://www.psrc.org/transportation/cmp/. [ Return to note 32. ] 33 Caltrans Office of Community Planning, Implementing the Smart Mobility Framework into a Sub-regional Long Range Transportation Plan, September 2014. Available at: http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/tpp/offices/ocp/Appendix_K_PA2_Recommendations_Report_Final.pdf. [ Return to note 33. ] 34 Caltrans, Smart Mobility 2010: A Call to Action for the New Decade, February 2010. Available at: http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/tpp/offices/ocp/smf.html. [ Return to note 34. ] |

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||