Advancing Transportation Systems Management and Operations Through Scenario PlanningSection 2: Understanding Scenario Planning and Its Use in TransportationWhat is Scenario Planning?Scenario planning is an approach to strategic planning that uses alternate narratives of plausible futures (or future states) to play out decisions in an effort to make more informed choices and create plans for the future. From a transportation systems management and operations (TSMO) perspective, a future state or condition might include narratives that prompt planners and stakeholders to consider what kind of TSMO response might be appropriate to different types (or frequency) of significant weather events, a future that assumes a more significant shift in traveler behavior to non-auto modes, or a future where 30 percent of the vehicles on the road are essentially "driverless." Considering scenarios like these can result in the identification of new technology or data needs, new technology investments, more communication and coordination across emergency response stakeholders, new multimodal TSMO strategies, and other insights that can be factored into both short- and long-term TSMO plans and programs. Scenario planning helps participants to consider the "what-ifs" of tomorrow, whether those are desirable or undesirable states. The simple task of imagining a different future can help to challenge the status quo and encourage creative thinking, which ultimately can lead to the development of more thoughtful and resilient plans. Scenarios are developed to enable participants to test out possible decisions, analyze their impacts given the conditions in each scenario, and come to an agreement on a preferred course of action. There are many definitions for scenario planning throughout literature and there are several variants on how to develop and use scenarios. Despite these variations, there are commonalities that provide structure to scenario planning. Scenarios are seen as "an internally consistent view of what the future might turn out to be—not a forecast, but one possible future outcome."1 This definition combines three key characteristics of scenarios:

Scenarios are neither forecasts nor predictions for a given point in time; instead, they represent alternative possible futures. They enable planners to consider a range of possible consequences the spectrum of possible future conditions. Scenario planning "formalizes the consideration of uncertainty in the planning process."2 Peter Schwartz, an international leader in the field of scenario planning, describes scenarios as "the best tool I know to allow the conversation to reflect different perceptions of the situation (differentiation), but in such a way to create room for people to consider these different viewpoints and gradually align on what needs to be done, and what they want to do (integration)."3 Advantages of Scenario Planning:

Scenario planning supports a dynamic planning process that can help demonstrate the causal relationships of different variables and how they combine to create different outcomes. This gives people the freedom to imagine that conditions could change in the future if given enough time. In the public sector, scenario planning is often applied to provide a forum for engaging diverse stakeholders, illustrating comparisons and discussing tradeoffs, and encouraging systems-level thinking that breaks down the silos of specialization to address challenging public policy issues. It helps people to envision not only what the future might be but also what kind of future people actually want. Scenario planning is a more deliberate process that uses empirical data and quantitative analysis to develop plausible scenarios. The Origins of Scenario PlanningThe origins of scenario planning in modern America are attributed to military planning methods that were developed during World War II and extended into the Cold War and beyond. The Air Force and other branches of the military would routinely envision possible combat scenarios and devise strategies to overcome their opponents.4 In the 1950s and 1960s, the RAND® Corporation helped to pioneer the science of scenario analysis, which relies on game theory. By the late 1960s, scenario planning was being applied regularly in corporate settings and has remained a common practice in business today. One of the seminal scenario planning efforts occurred in the 1970s when Royal Dutch Shell used scenario planning to prepare for potential events causing oil prices to change. In part due to that effort, Royal Dutch Shell was able react quickly to the fuel shortage and high oil prices set off by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' oil embargo of 1973.5 The company continues to practice scenario planning to this day.6 Scenario Planning in TransportationIn transportation, scenario planning began taking hold in the United States in the early 1990s as a method to help support alternative analysis practices developed under the National Environmental Policy Act and the "3C" (comprehensive, continuous, coordinated) systems planning requirements of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1962.7 In the early 2000s, the Transportation and Community and System Preservation Pilot Program (TCSP) resulted in the creation of some of the early tools and processes for incorporating scenario planning into the development of long-range transportation plans. These early efforts focused almost entirely on examining alternative land use and transportation futures that emphasized desirable stories and narratives for how communities wanted to grow. As a result, many of the early scenario planning processes resulted in public policy shifts that enabled much stronger links between land use and transportation planning. More recently, scenario planning in transportation has begun to examine a broader range of variable relationships beyond just land use and transportation. These include scenarios that take into account goals and objectives related to housing affordability, economic competitiveness, adapting to climate change, water conservation, fiscal sustainability, public health, and energy conservation. This broadening of factors is generating more integrated plans and policies as communities gain a better understanding of the connections between factors such as housing affordability and transportation accessibility or reductions in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and better public health outcomes. Key Elements of Scenario Planning "While scenario planning can be implemented in many ways, the key elements include:

Scenario planning shares common elements with both alternatives analysis and visioning exercises, but primarily differs from these processes in examining interactions between multiple factors, including both internal and external forces, as a way to assess possible future outcomes."8 Scenario planning is making a difference in areas where it is used as part of transportation planning efforts. Scenario planning can help agencies to convey critical information to policy makers and elected officials who make investment decisions. For example the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) addressed the linkages between funding and system management performance in its 2035 statewide plan by constructing three investment scenarios, each of which forecasted anticipated performance based on investment levels. Given forecasted revenues, pavement condition would deteriorate to the point at which only 25 percent of roads would be in good/fair condition, while congestion would increase to 70 minutes of delay per traveler. CDOT developed alternative revenue scenarios to demonstrate the "cost to sustain current performance" and the "cost to accomplish [a] vision" that had been laid out in the statewide long-range plan. This valuable information helped decision makers to clearly understand how funding shortfalls would affect system performance. Scenario planning helps agencies to build relationships and forge partnerships that can strengthen their effectiveness and build their capacity. For example, the Champaign-Urbana Urban Area Transportation Study (CUUATS), the metropolitan planning organization (MPO) for a university town in Illinois, has applied scenario planning techniques to a series of studies that engaged an ever-expanding array of interest groups and agency stakeholders. The resulting strong relationships with various local and State agencies and other organizations (including the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) have been critical to CUUATS for obtaining data, developing innovative technical analysis tools, leveraging transportation investment funds, and building political support for regional initiatives. Long-range planning and scenario planning processes have worked smoothly in significant part because of the high degree of collaboration and coordination among local agencies. Scenario planning can help transportation practitioners and policymakers better prepare for the future by encouraging an examination of different future conditions that get beyond just an extrapolation of current trends. As explored in the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Report 750: Strategic Issues Facing Transportation, there are several key trends that will significantly impact transportation in the coming decades. Scenario planning can be a useful tool for better understanding the potential impacts of those trends and planning accordingly for system resiliency, shifts in travel behavior and travel demand, and the rapid advances in technology. Scenario Planning to Strategically Address Driving Issues Affecting the Future of Transportation The National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) issued NCHRP Report 750: Strategic Issues Facing Transportation in an effort to compile research and provide practitioner guidance for addressing climate change, socio-demographic shifts, technology advances, freight and goods movement, alternative energy and fuels, and sustainability. These six topic areas are seen as having a significant impact on how we will plan, fund, build and operate our transportation systems in the future. Six separate reports summarize these research efforts: Volume 1: Scenario Planning for Freight Transportation Infrastructure Investment Volume 2: Climate Change, Extreme Weather Events, and the Highway System – Practitioner's Guide and Research Report Volume 3: Expediting Future Technologies for Enhancing Transportation System Performance Volume 4: Sustainability as an Organizing Principle for Transportation Agencies Volume 5: Preparing State Transportation Agencies for an Uncertain Energy Future Volume 6: The Effects of Socio-Demographics on Future Travel Demand The documents are available at: http://www.trb.org/NCHRP750/ForesightReport750SeriesReports.aspx. Each report addresses issues relevant to long-term thinking about management and operations, offering again some key drivers that could help transportation systems management and operations (TSMO) planners envision different scenarios and appropriate corresponding management and operations responses. For example, Volume 2 provides a practitioner's guide and research on specific weather and climate trends as well as how those conditions may potentially impact events on the highway system. It cites several adaptation strategies that will likely be needed for transportation agencies with respect to network operations:

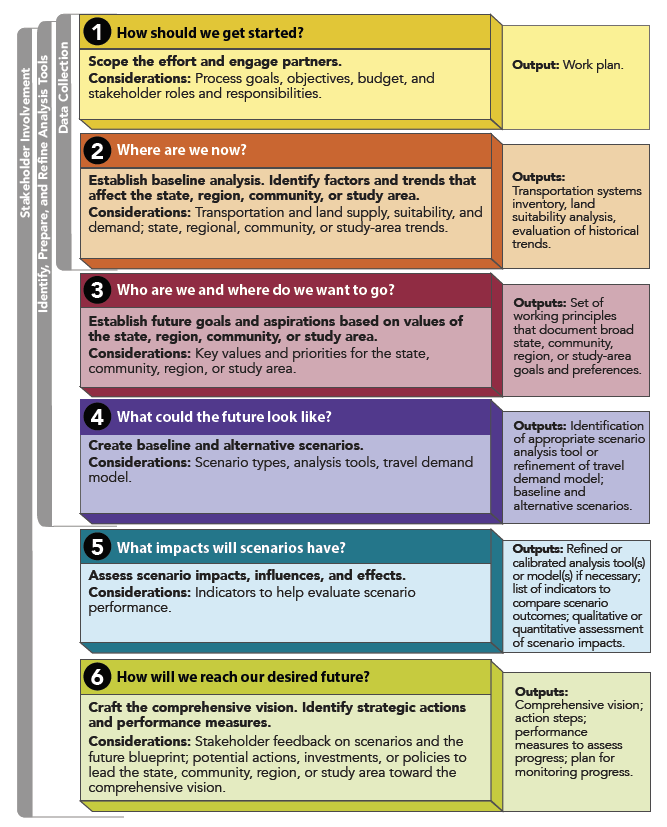

Given the emerging science and research on climate change, scenario planning techniques may be useful in helping TSMO planners and other stakeholders determine how best to identify and incorporate adaptation strategies into regional TSMO plans. In particular, considering that extreme weather events are predicted to increase in many regions across the country, scenario planning could be an effective approach to helping States and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) bring together the interagency stakeholders needed to effectively address the issue. Doing so will not only bring the right people to the table, it may also aid in helping to set expectations among planners and even the general public on acceptable levels of system performance under extreme conditions. Finally, the scenario process might also aid the region in better understanding its areas of susceptibility, thereby further helping to refine and strategically deploy TSMO strategies. The NCHRP Report 750 series not only contains information on some of the driving factors that will influence transportation in the future, it also includes specific examples and tools for using scenario planning as a means for addressing those factors. Federal Highway Administration Scenario Planning FrameworkIn 2011, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) published the FHWA Scenario Planning Guidebook, which outlines key phases associated with transportation scenario planning, as illustrated in Figure 1.  Figure 1. Illustration. The Federal Highway Administration's Six-Phase Scenario Planning Framework.9 The guidebook offers a structure for scenario planning that aligns well with traditional transportation planning processes. The guidebook focuses primarily on how to apply scenario planning on a regional scale; however, these same phases and steps can be applied to statewide, corridor-level, or neighborhood-level approaches and across short-term or long-term planning horizons. Per FHWA, these are suggested phases, but each location using scenario planning has unique situations, and these phases can be adjusted to fit each community's individual needs. For example, some communities might be much further along in their data collection efforts and could skip Phase 2.

This use of scenario planning has several benefits as well as costs in terms of a lead organization's human and technical resources as shown in Table 1.

Using Scenario Planning in Performance-Based Planning and ProgrammingScenario planning is an important tool for performance-based planning and programming and is specifically encouraged by Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21) for the development of metropolitan transportation plans.10 The passage of the MAP-21 in 2012 created requirements for performance-based planning and programming (PBPP) within metropolitan, statewide, and nonmetropolitan decisionmaking. PBPP applies performance management principles to transportation planning and programming to achieve desired performance outcomes for the multimodal transportation system. This is accomplished by incorporating goals and objectives, performance measures and targets, and regular progress reporting into transportation decisionmaking. Scenario planning can be used at multiple points within the PBPP process to help stakeholders determine their desired strategic direction. Starting with a baseline analysis ("where are we now?"), scenario planning enables stakeholders to establish future aspirations based on their values. This process can involve a specific discussion of goals, supporting objectives, and performance measures based on these values. The scenario planning approach helps visualize and articulate, in both qualitative and quantitative terms, how the combination of strategies would help meet public policy goals and performance targets. It allows for the consideration of how various factors, such as revenue constraints, demographic trends, economic shifts, or technological innovation, can affect a State or region and its transportation system performance. The analysis may allow stakeholders to explore the trade-offs between future scenarios, assess the impacts of external factors such as the economy and growth, and select a future vision and investment priorities that bring them closest to their desired performance outcomes. Through the use of scenario planning, metropolitan, statewide, and other planning organizations are able to take a comprehensive approach to PBPP by exploring multiple potential futures and making a well-informed selection of a preferred alternative with the most potential for supporting priorities and performance targets. The following text box provides two examples of scenario planning applied to broader planning contexts in which TSMO is one of multiple solutions brought together to address a problem or achieve a vision. Plan Bay Area The Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), the metropolitan planning organization (MPO) for the San Francisco Bay Area, and the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) used scenario planning as part of their performance-based planning approach to developing the California Bay Area's integrated land-use, housing, and long-range transportation plan, called Plan Bay Area. First, the agencies developed performance targets for the plan. The transportation-related performance targets they identified are shown in the figure below. The agencies then developed scenarios containing different combinations of growth patterns, transportation, and land use strategies and analyzed them to see which scenarios came closest to achieving the performance targets. The agencies used different tools to analyze each performance target. For Target 9 (see Figure 2), MTC's activity-based Travel Model One was used, and for Target 10, post-processing methodologies developed by MTC were used to estimate future road and transit conditions.11 MTC and ABAG conducted two rounds of developing and analyzing scenarios, which included investments in programs such as a Freeway Performance Initiative (which included intelligent transportation systems (ITS), ramp metering, traffic operations systems, arterial management strategies) and an express lanes network.13 The quantitative analysis showed that none of the scenarios were able to meet all of the specified performance targets, and some of the targets were not met by any of the scenarios. In addition, to analyze the scenarios, the agencies conducted assessments of all non-committed transportation projects contained within the scenarios. Several findings resulted from the project-level assessments. First, ITS technologies and congestion pricing programs proved to be highly cost effective and met many performance targets. In addition, the results showed that express lanes are only moderately cost-effective due to high capital costs, and they tend to increase automobile capacity, which negatively impacted performance targets.14 As a result of the project-level assessments, high-performing projects were incorporated into the transportation strategy included in the "preferred scenario" developed in the spring of 2012. This scenario, called the "Jobs-Housing Connection Strategy," included a transportation investment strategy that "devotes 87 percent of funding to operate and maintain the existing transportation network."15 "What Would It Take?" Scenario Study in the National Capital Region The Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments' Transportation Planning Board (TPB) conducted the "What Would it Take?" Scenario Study in 2010 to identify strategies to help the region achieve its greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals. To complete the study, the TPB conducted an emissions baseline inventory and forecast for the region and determined three sources for reducing emissions: fuel efficiency, alternative fuel, and travel efficiency. Then they identified 37 potential transportation strategies that could be used to reduce emissions and used sketch planning methods to analyze each of these strategies individually for emissions reduction potential, cost-effectiveness, and timeframe for implementation. The top scoring strategies were grouped into two categories or scenarios based on the level of government that would be implementing the strategies:17 High Federal Role – Examines the impact of "hypothetical, large-scale action taken by the federal government,"18 including enhanced light duty and heavy duty Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards and high gas prices. State/Regional/Local Action – Examines the impact of current Federal legislation combined with short-term and long-term actions undertaken by State and local governments. Short-term (pre-2020) actions include strategies such as transit signal priority, incident management, traffic signal optimization, and transportation demand management (TDM) programs. Long-term actions include increasing non-auto mode share, implementing pricing on new and existing roadways, and reducing travel through transit-oriented land use development. The study results showed that while neither category would meet the region's emissions reduction goals, the short-term scenario strategies "position the region toward meeting early targets."19 The study team concluded that meeting the emissions reduction goals would require incorporating more aggressive strategies into all of the scenario categories and conducting additional analysis.20 There are many contexts in which scenario planning can be used to advance TSMO. In the Plan Bay Area and National Capital Region "What Would it Take?" planning efforts, the scope included TSMO as one of many transportation strategies. Alternatively, scenario planning can be used to look exclusively at TSMO and answer the questions necessary to create TSMO-oriented plans or make decisions about how to move ahead with TSMO goals, objectives, strategies, and investments. This primer will discuss several opportunities and hypothetical illustrations of using scenario planning for TSMO. As a preview, Table 2 provides a sample of the TSMO contexts for scenario planning use that will be covered in later sections.

1 M. Porter, Competitive Advantage (New York: Free Press 1985). Return to note 1. 2 J. Zmud, Transportation Research Board Webinar, "Applying Scenario Methods to Transportation Planning and Policy," October 23, 2014. Slides available at: http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/webinars/141023.pdf. Return to note 2. 3 P. Schwartz, as quoted in Kees van der Heijden, Scenarios: The Art of Strategic Conversation (New York: Wiley and Sons, 2005). Return to note 3. 4 C. Caplice and S. Phadnis, NCHRP Report 750: Strategic Issues Facing Transportation, Volume 1: Scenario Planning for Freight Transportation Infrastructure Investment (Washington, DC: National Cooperative Highway Research Program, 2013). Available at: http://www.trb.org/main/blurbs/168694.asp. Return to note 4. 5 Ibid.. Return to note 5. 6 Shell Global, "40 years of Shell Scenarios," Web Page. Available at: http://www.shell.com/global/future-energy/scenarios/40-years.html. Return to note 6. 7 K. Bartholomew and R. Ewing, Integrated Transportation Scenario Planning, Metropolitan Research Center, University of Utah. July 2010. Return to note 7. 8 U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, FHWA Scenario Planning Guidebook, FHWA-HEP-11-004 (Washington, DC: FHWA 2011). Return to note 8. 9 U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Scenario Planning Guidebook (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2011). Available at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/scenario_and_visualization/scenario_planning/scenario_planning_guidebook/. Return to note 9. 10 23 USC Section 134(i)(2)(C). Return to note 10. 11 Association of Bay Area Governments and Metropolitan Transportation Commission, Plan Bay Area – Performance Assessment Report, July 2013. Available at: http://onebayarea.org/pdf/final_supplemental_reports/FINAL_PBA_Performance_Assessment_Report.pdf. Return to note 11. 12 Ibid. Return to note 12. 13 Metropolitan Transportation Commission, Transportation 2035. Available at: http://www.mtc.ca.gov/planning/2035_plan/FINAL/T2035_Plan-Final.pdf. Return to note 13. 14 Ibid. Return to note 14. 15 Association of Bay Area Governments and Metropolitan Transportation Commission, Plan Bay Area – Performance Assessment Report, July 2013. Available at: http://onebayarea.org/pdf/final_supplemental_reports/FINAL_PBA_Performance_Assessment_Report.pdf. Return to note 15. 16 Ibid. Return to note 16. 17 M. Bansal and E. Morrow, Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, "Meeting Transportation Greenhouse Gas Reduction Goals in the National Capital Region: A 'What Would it Take' Scenario," July 2010. Available at: http://www.mwcog.org/clrp/elements/scenarios/whatwouldittakeTPB_TRB_Resubmit.pdf.Return to note 17. 18 Ibid., p. 10. Return to note 18. 19 National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board, What Would it Take? Transportation and Climate Change in the National Capital Region, Final Report, May 2010, p. vii. Available at: http://www.mwcog.org/uploads/committee-documents/kV5YX1pe20100617100959.pdf. Return to note 19. 20 Ibid. Return to note 20. | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||