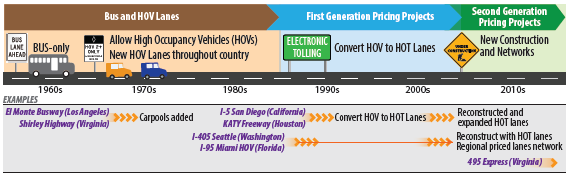

Congestion Pricing - A Primer: Evolution of Second Generation Pricing ProjectsWhat are Second Generation Congestion Pricing Projects?Second generation congestion pricing projects had their genesis over 40 years ago, when high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes were created on urban freeways. These projects aimed at maximizing vehicle occupancy and person throughput on freeways by restricting use of a lane or lanes for buses, carpools and vanpools. HOV lanes became a "relied upon approach to lane management." (1) Over the years, HOV lanes became either too successful or not successful enough. The result was a situation where the lanes were either over-crowded or under-utilized, both of which created dilemmas for decision makers. The emergence of electronic tolling offered the ability to "better manage dedicated lanes through both eligibility restrictions and pricing." The term high-occupancy toll (HOT) lane was introduced as the first generation of priced managed lanes, in which HOVs continue to travel free with ineligible vehicles paying for the privilege of using the lane. The HOV to HOT conversions have helped to blunt criticism of HOV lanes and have opened new opportunities to manage travel demand. Since the 1990s, pricing has become a preferred strategy by states and regions for efficiently managing the available capacity in the lanes. First-generation HOT lanes offered a solution: convert the existing HOV lanes into priced facilities, keeping the HOV priority but selling any unused capacity to users willing to pay for the privilege of saving time within the HOT lanes. This worked well for HOV projects where the HOV lanes were under utilized, since there was plenty of capacity to sell and nobody was inconvenienced. The Federal Highway Administration Role in Roadway Pricing Since 1992, the Value Pricing Pilot Program (VPPP, formerly Congestion Pricing Pilot Program) has played an essential role in the development and deployment of road pricing throughout the United States. As congestion pricing was being introduced and proposed on projects (mostly high-occupancy toll (HOT) lane conversions) in major cities, it was perceived as a radical concept. Sponsors of early projects were faced with opposition regarding several key issues that were common across the country. It is likely that several of the initial projects that were supported by the VPPP may not have occurred, had there not been this national focus and shared research. Grant funding from VPPP provided support for State and local transportation agencies to test the concept of congestion pricing in their regions. The early projects performed essential research into critical issues such as equity, privacy, enforcement, outreach, and revenue generation potential that were common to many of the projects. These projects also examined potential threats that would potentially derail them. The Congestion Pricing program's most important contribution to the industry is its continuing support for early research on these issues and testing of operational schemes and technology. The same projects that experienced several setbacks due to these critical issues (up to a decade to complete) set the stage for far more significant priced roadway facilities and networks (second generation projects) in their regions. By charging a fee for other vehicles, pricing could help ensure that demand would not exceed capacity.(1) The implied "win-win" solution would demonstrate that:

At the other extreme, over-used HOV lanes faced a situation where the HOV occupancy definition needed to be raised, usually from 2+ to 3+, in order to maintain acceptable travel speeds. Changing the occupancy definition to 3+ would fix the HOV lane operational problems, but the pendulum could quickly swing to an empty-lane syndrome with too few HOV 3+ vehicles. Pricing offers the opportunity to shift to an HOV 3+ operation while allowing other vehicles, including HOV 2 vehicles, to buy into the lane capacity and maintain more optimal freeway lane operations. While operationally efficient, the decision to charge new tolls to HOV 2 users has been a difficult process in several regions.

1 Eligible HOVs use the facility free and unregulated by price.

2 Efficiency is gained by fully regulating access to the priced lanes. Second generation priced lane facilities could have the option to charge all vehicles. HOT = high-occupancy toll, HOV = high-occupancy vehicle Source: Adapted from D. Ungemah, "HOT Lanes 2.0- An Entrepreneurial Approach to Highway Capacity," Presentation Slides for National Road Pricing Conference in Houston, TX, June 2010  Figure 1. Illustration. Timeline Depicting The Evolution of Roadway Pricing from the 1960s through Today. How Are First and Second Generation Priced Lanes Different?As the first generation high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) to high-occupancy toll (HOT) conversion projects have matured, there has been a movement to "second generation" priced lanes. Second-generation projects include one or more of the following features: the extension of existing HOT lanes, provision of newly constructed priced lanes, and the development of priced lane networks. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Priced Managed Lane Guide(4) provides a good summary of this evolution (see chapter 1, page 1-11):

Table 1 contrasts some of the major characteristics between the first and second-generation projects. Types of Second Generation Pricing ProjectsThe second-generation projects have been implemented on the following facility types:

New Roadway CapacityRecognizing the limited capacity of a single HOV/HOT lane to accommodate future travel demands, projects have emerged that have added roadway capacity to create a dual-lane priced facility. The extension of the I-15 HOT lanes in San Diego2 is a good example of a facility that was designed to meet the growing travel demands in the corridor while maintaining priority for HOVs and transit. Challenges of a Priced Managed Lane Network

Other regions were faced with the need to add roadway capacity and determined that building managed lanes provided better freeway operations and gave them the flexibility to manage the facility to meet changing demands. These projects to add capacity have needed to address directly the tradeoffs between user eligibility (e.g. transit, carpools, vanpools, and single occupant vehicles), pricing levels, and funding opportunities. Adding pricing to the equation enhances agencies' ability to manage demand while providing needed funding to cover a portion of the costs. Typically, priced managed lanes have provided funds to cover all or a portion of the operations and maintenance costs. Unlike fully tolled roadways, managed lanes do not usually provide pricing revenues sufficient to fully fund the construction costs of the lanes. Second-generation "express toll lanes" (ETLs)3 offer greater revenue generation potential, but are also more expensive to construct. Networks of Priced Managed LanesAnother defining feature of second-generation projects is the ability to create networks of priced managed lanes. Over the years, regions have developed high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lane systems to provide continuous priority treatments for carpools and transit. Many transit agencies rely on a network of HOV lanes to provide reliable freeway bus rapid transit (BRT) service. Major investments in HOV direct access ramps, transit centers, and park-and-ride facilities usually augment the HOV lanes. As the HOV lanes have become more crowded, the reliability of bus service has diminished in several regions, creating a need to better manage demand in the lanes. Regions have responded by converting the HOV lanes to networks of priced managed lanes. In the San Francisco Bay Area, a network of priced managed lanes was adopted as the regional strategy by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC). Other examples include HOT-networks underway in Atlanta, Dallas, Minneapolis, Seattle, San Diego, South Florida, Houston, Northern Virginia and Los Angeles. Agencies have found that creating a priced managed lane network is more complex than converting existing HOV lanes to HOT lanes. While some regions are turning HOV networks into HOT networks, other regions are building on the success of single-facility priced managed lanes. Experience has shown that once a priced lane has been in operation and is understood by the public, it has created opportunities to either extend the managed lanes on the existing facility (e.g. I-15 in San Diego; SR 91 in Orange County, I-95 in Miami) or to connect two or more HOT/ETL facilities (e.g. I-495 and I-95 in Northern Virginia). While geographical expansion does create technical challenges, more often it is the institutional issues that become the most complex, since more agencies and interest groups become involved. Priced Managed RoadwaysAs multiple-lane priced managed lanes become part of the mainstream, it is not difficult to envision a future of fully priced roadways where total demand is managed through a combination of pricing and operational strategies. Fully priced facilities are different than toll roads, which are priced for the purpose of generating revenues and usually are not focused on managing demand. Conversely, fully priced managed roadways would have two functions: managing demand and generating revenue. These two functions can conflict with each other, but the concept of priced managed roadways would be to balance the desire for generating needed transportation funds with ensuring that the roadways are operating as efficiently as possible. The policy framework for priced managed roadways is being established in some regions. For example, the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) in Seattle has adopted its 2040 transportation vision that assumes that all major freeways would be actively managed and priced. Currently, the region's extensive HOV lane network is being transformed into a HOT network, but the ultimate plan is to fully price and manage the freeways. One starting point is the SR 520 Bridge, which is currently tolled and managed using variable pricing. The bridge is tied to HOV lanes on one end, but HOVs (except transit and vanpools) do not receive any toll discount.4

As second-generation projects mature, new challenges and opportunities have emerged, as summarized in Table 2. These issues are explored further using case study examples. Each case study also includes text boxes that note the evolution of managed lanes and one that defines the FHWA role. 1 Since 2012, Dallas has also adopted a regional managed lane plan. [ Return to note 1. ] 2 SR 91 in Orange County, CA was actually the first HOT lane (1995), but it was not designed with HOV and transit priority in mind. [ Return to note 2. ] 3 The Priced Managed Lane Guide distinguishes HOT lanes, where qualified vehicles travel at no cost, and ETLs, where all vehicles pay a variably priced toll to use the lanes. In practice, there are projects that are using the term "express toll lane" or "express lane" more generically to denote a priced managed lane that may or may not charge a toll to HOVs. [ Return to note 3. ] 4 The SR 520 bridge project was the recipient of FHWA funds through the Urban Partnership Agreement (UPA) program. [ Return to note 4. ] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||