Applying the Principles of the Work Zone Rule to Design-Build Projects, Two Case Studies

5. North Carolina I-85 Corridor Improvement Project

This section presents an overview of the I-85 Corridor Improvement project and observations and findings from the case study. It identifies successes, issues, and challenges when applying the Rule during the project development and implementation phases.

Background and Specifications

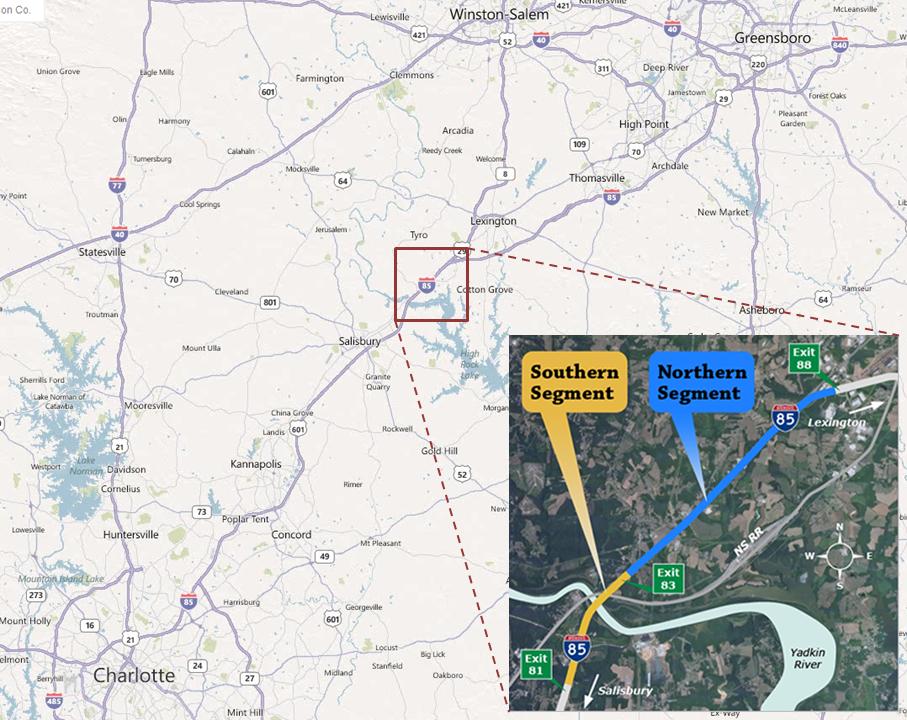

The I-85 Corridor Improvement Project was located in Central North Carolina, half way between Charlotte to the south and Greensboro to the north (see Figure 5-1). The project was split into two segments. Each segment of the project was let as an individual design-build contract, with a different design-build team selected for each segment. The two segments are the I-2304 AC (the southern segment) and I-2304 AD (the northern segment). I-85 is the primary route between Montgomery, Alabama and Atlanta to the south, through Charlotte, Greensboro and Durham, and north to Richmond, Virginia. As it passes through the work zone, I-85 carries about 65,000 vehicles per day (vpd), 25-40% of which are commercial vehicles. The southern segment includes the I-85 Bridge over the Yadkin River, the only major vehicular crossing for many miles. Figure 5-2 illustrates the locations of the I-85 Bridge and other bridges over the Yadkin River.

Figure 5-1. I-85 Project Location

(Source: NCDOT and URS Group, Inc.)

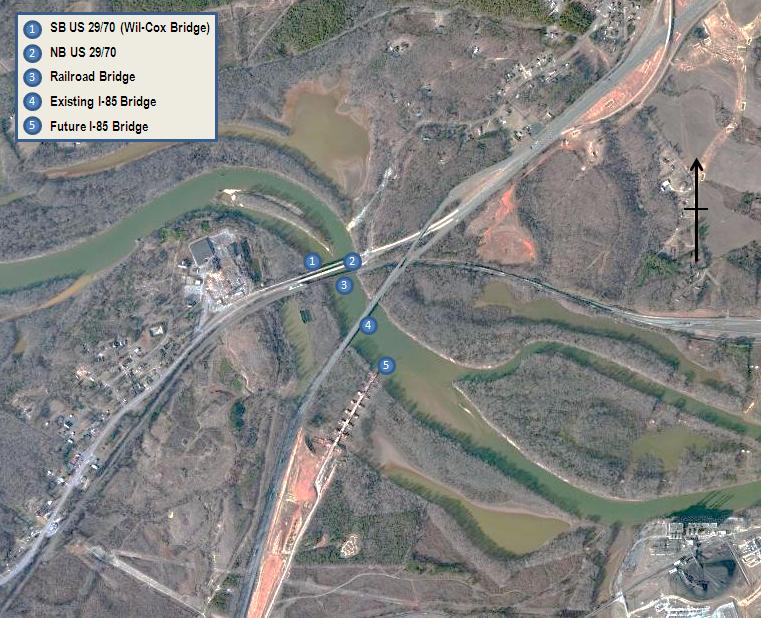

Figure 5-2. Locations of Yadkin River Bridges

(Source: URS Group, Inc.)

The AC project was awarded in April of 2010, and construction began in late September of that same year. Four months later in January of 2011 the AD project was awarded, and construction on the northern segment began in May of 2011. The projects ran concurrently for almost two years, until Spring 2013.

The following were the primary elements of each of the segments:

I-2304 AC - $136 million southern segment:

- Replacement of the I-85 Bridge over the Yadkin River (bridge #4 in Figure 5-2). The new bridge (bridge #5 in Figure 5-2) has one structure for each direction of traffic.

- Conversion of the Southbound US 29/70 Bridge (bridge #1 in Figure 5-2) to a pedestrian/bicycle bridge.

- Replacement of the Northbound US 29/70 Bridge (bridge #2 in Figure 5-2) with a new single-structure bridge for both direction of travel.

- Widening I-85 from four to eight lanes through the length of the project (about 3.3 miles).

- Reconstructing the I-85 interchange with N.C. 150.

- Removing the I-85 interchange at Clark Road.

I-2304 AD - $66 million northern segment:

- Widening I-85 from four to eight lanes through the length of the project (about 3.8 miles).

- Reconstructing the I-85 interchange with Belmont Road.

- Reconstructing, realigning, and building secondary roads that support the Interstate and the access roads.

The I-85 Corridor Improvement Project addressed several needs and mitigated problems with the current operation of the facility:

- Previous projects had widened I-85 from four to eight lanes south to Charlotte, and this segment had become a bottleneck.

- Originally designed and constructed in the 1950s, this segment of I-85 had narrow lanes throughout and tight curves entering and exiting the bridge as illustrated in Figure 5-3. Figure 5-4 shows the new straighter bridge alignment.

- The crash rate for I-85 in this area was over 75% higher than the State average for similar roadways.

- The I-85 Bridge over the Yadkin River was rated in poor condition and classified as structurally deficient and functionally obsolete.

- The parallel bridges carrying US 29/70 over the Yadkin River were also in poor condition and structurally deficient. Southbound US 29/70, the Wil-Cox Bridge built in 1922, had been closed and turned over to Davidson County as part of a planned regional greenway system.

- There is a heavily utilized truck stop with scales on the northwest quadrant of the Belmont Road Interchange. The exit ramps were not of modern design and led to heavy vehicles starting their deceleration on the I-85 mainline.

Figure 5-3. Existing Bridge Approach

(Source: URS Group, Inc.)

Figure 5-4. New I-85 Alignment from the North

(Source: URS Group, Inc.)

The segments of the project were originally identified as two separate projects, I-2304 AA and AB. NCDOT was prepared to proceed with the projects in 2004, but budgetary issues prevented the contracts from being executed. After that time, the overall project continued to be viewed as one of the highest priority projects in the State. Funding for the project was finally secured from several sources and the AC project was let in 2010. The funding for the southern AC project came from a Federal TIGER grant, the State's Transportation Improvement Program, and Grant Anticipation Revenue Vehicles (GARVEE) bonds, which borrow from expected future funds. The northern AD project was the first project funded by the North Carolina Mobility Fund. The winning AD project bid came in at almost half the estimated $130 million.

The RFPs for each project devoted a high percentage of the evaluation points to the maintenance of traffic and safety plan (MOT), Schedule and Milestones, and Innovation. The AD project had more points for MOT (25 out of 100) than the AC project (15 out of 100) because it involved much more traffic management, traffic control, and work in the right-of-way. Schedule and Milestones was worth 30 points for the AD project and 23 on the AC project, while Innovation was worth eight points for the AC project and four for the AD project. Extra credit was available on both projects for additional warranties or guarantees.

Many different types of meetings created a good partnering environment early on in the projects, and encouraged partnering and positive sharing of ideas as the projects continued. These meetings included:

- Partnering and Conflict Management Meeting, prior to notice to proceed. This was a meeting between the designers on the winning design-build team and NCDOT to discuss and establish quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) and NCDOT review processes.

- Incident Management Meetings: These meetings were held every four to six weeks with involvement from both of the Contractors, NCDOT WZTC staff, Highway Patrol, local law enforcement and other emergency responders, the Resident Engineers, and Incident Management Assistance Patrol (IMAP) personnel.

- Traffic Safety and Operations Meetings: These meetings were initially held monthly, then changed to quarterly once the AD project was underway. The meetings involved the designers, construction staff, and Resident Engineers for each of the projects, as well at WZTC staff.

- Construction Meetings. Meetings were held weekly. WZTC staff would attend these meetings if there was a traffic shift or detour that needed to be discussed. The NCDOT Public Information Officer also attended the meetings, as needed, to be kept aware of the project progress and status.

These planning and coordination meetings between the two projects helped NCDOT meet its goal of having the public see the two segments as one continual project, even though I-2304 AC and I-2304 AD were different contracts. With good collaboration and cooperation between the two projects and their traffic control and work zones, drivers should not have noticed where the AC project ended and the AD project began. Another way to meet the goal was the joint website for the projects (www.i-85yadkinriver.com).

NCDOT had a website for the I-85 Corridor Improvement Project which was set up by the Contractors. The website explained that the project was being built in two separate phases, and then described the details of each "phase." The home page of the website had a map and brief overview of the project and then allowed users to choose between the two project segments. Each segment had its own description, but referenced and linked back to the other. The website was initially set up by the AC Contractor, and then when the AD project started it was integrated into the original AC website. There were no provisions in the RFP for the websites to be combined, but both Contractors worked together as they realized the benefit of the public viewing these projects as one. NCDOT noted that for design-bid-build projects the two websites would have been done internally and it would have been difficult to integrate them because of lack of resources and limitations on some capabilities (e.g., video) and formats. NCDOT indicated that the design-build teams were able to provide a better website with more information, as a DOT led website for the project would have been more generic and provided fewer capabilities.

Application of the Work Zone Safety and Mobility Rule

This section examines each of the eight key Rule aspects identified earlier, and discusses successes and challenges in applying each aspect to the I-85 Corridor Improvement project.

Key Aspect #1 - Work Zone Assessment and Management Procedures

This aspect encourages States to develop and implement systematic procedures to assess work zone impacts in project development and manage safety and mobility during project implementation.

Successes

- Decision-making on work zone traffic control was based on the overall goal of providing for a safe and efficient work zone. NCDOT policies and guidelines, including its Draft Guidelines for the Implementation of the Work Zone Safety and Mobility Policy, were applied to the project. The Guidelines establish processes and procedures for work zone traffic control decision making and evaluation. Decisions based on the guidelines were included in the RFP requirements, and the design-builder developed the TMP based on the requirements. During construction, NCDOT monitored the work zone traffic conditions via CCTV cameras on an as needed basis. Portable DMS were used to alert travelers of work zone conditions and incident information. The project was still under construction as of the writing of this case study, and no significant delay or safety impacts had been encountered to date.

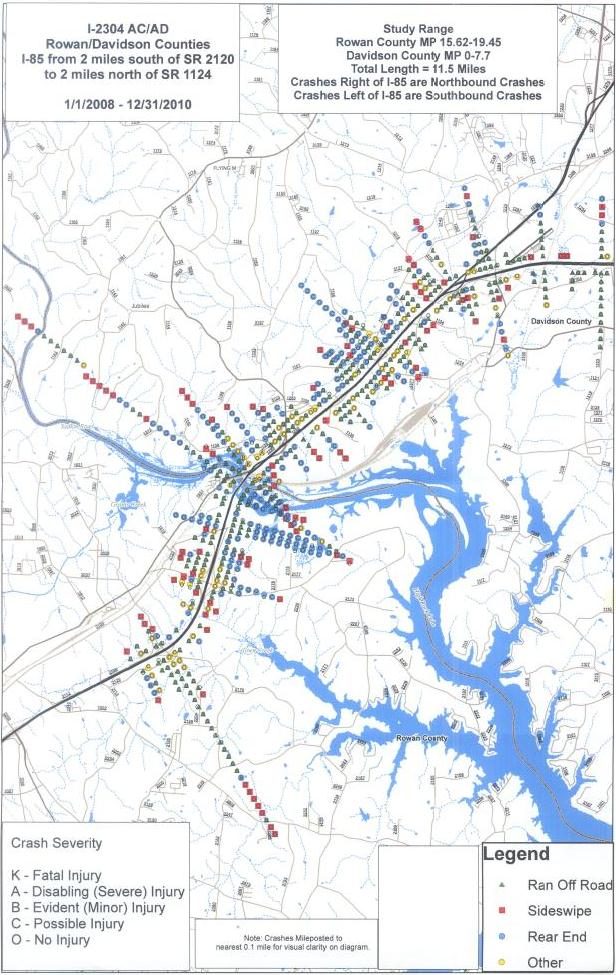

- In the three years prior to starting the AC project, the segment of I-85 that both of these projects covered experienced a high rate of crashes. In an 11.5-mile segment extending about two miles beyond the north and south limits of the projects, there were 672 reported crashes from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2010 (average of 224 per year), including two fatalities. Project designers used this crash information (see Figure 5-5) to help solve issues for the final design. For example, a truck stop was located near the Belmont Road Interchange. The existing off-ramps at this interchange were very short, and resulted in trucks decelerating and often queuing on the I-85 mainline. Crash data showed a high number of rear-end crashes in this area. The Contractor, with input from NCDOT, used the crash information to determine staging and traffic control to maximize the lengths of merge/diverge areas. Because of the limited room in the construction area at the Belmont Road Interchange, some of the staging plans used an alternate interchange for vehicles to access the truck stop and Belmont Road. Though vehicles had to travel a bit farther using the alternate intersection, the safety and mobility of the roadway was improved. In addition, the new design for this interchange provided auxiliary lanes for exiting vehicles and longer off-ramps. The new facility would reduce the number of crashes in the area near this interchange by separating the exiting vehicles from the faster moving through vehicles.

- NCDOT felt that including law enforcement agencies and first responders early in the incident management planning during project development was critical to enhance work zone safety and mobility. While early engagement of incident management stakeholders in the RFP development and design stages for traditional design-bid-build projects is important, it is even more critical for design-build projects because the development of the TMP and incident management plans are turned over to the Contractor prior to completion of the final design plans. For a design-build project, early engagement and participation from incident management stakeholders helps with building goals and expectations into the RFP to ensure the Contractor clearly understands the safety and mobility needs and the expectations of the Agency, and can develop plans that meet project requirements.

- The RFPs required the design-build teams to each designate a Quality Control Manager who is responsible for implementing and monitoring the quality control requirements of the projects. The design-build team was required to describe its compliance with the requirements for quality control of design and construction. NCDOT felt it was very important that the teams' designers followed the quality policies established by the design-build teams, as the NCDOT's review period for work zone and traffic control plans was only 10 days. At the time of the field review of this case study, the NCDOT work zone team had only missed one of the 67 ten day review deadlines. These types of short deadlines for plan review are not a significant factor in design-bid-build projects because the plans are developed under the DOT's direction prior to when the project goes to bid and are reviewed then.

- To manage impacts to motorists, NCDOT has included in its design-build contracts a note that the Contractor cannot install barrier more than two weeks before they will be working in that area.

Figure 5-5. Pre-project Crash Data (based on 3-year Data)

(Source: NCDOT)

Issues and Challenges

No issues were identified regarding the implementation of this aspect.

Key Aspect #2 - Work Zone Data Collection and Analysis

At the project level, States are required to use field observations, available work zone crash data, and operational information to manage work zone impacts for specific projects. At the agency level, States are required to continually pursue improvement of work zone safety and mobility by analyzing work zone crash and operational data from multiple projects to improve State processes and procedures over time.

Successes

- A good example of partnership and collaboration between the two projects is the monthly Incident management meeting. Attendees at this meeting include members from the design-build team and NCDOT for both projects, NCDOT WZTC staff, North Carolina Highway Patrol, local law enforcement, and first responders from the area. Crash data and history as well as speed enforcement are the major elements reviewed and discussed at these meetings.

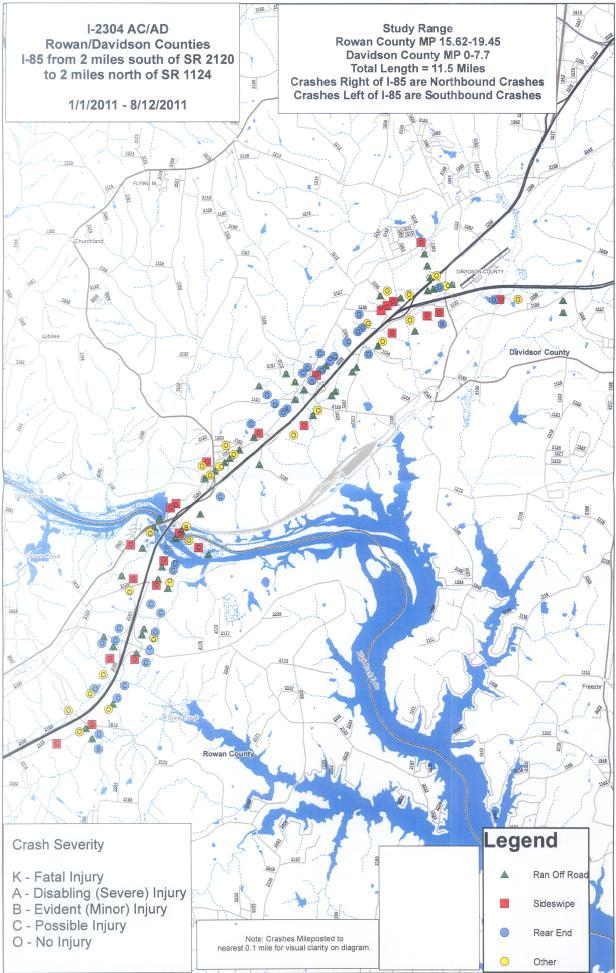

- Because NCDOT had good baseline crash data for a period prior to construction, they were able to determine some of the effect the work zones and traffic control had on crashes and the safety of the project corridor. The Highway Patrol emailed NCDOT crash data every one to two weeks. Because it was a design-build project, NCDOT was able to work with the Contractor and used this information to remedy conditions that led to repeat or similar crashes. Figure 5-6 shows crash data for the first seven-plus moths during the project. Comparing this data to the crash history of the area showed that the crash rate had not increased with work zones and construction activities, and the severity of the crashes had decreased. This crash analysis was done on an ongoing basis to quickly identify and address work zone crash issues.

Issues and Challenges

The RFPs did not require the Contractors to collect or analyze operational data to manage work zone impacts. It would be beneficial to include requirements in the RFPs for the Contractors to provide work zone monitoring and/or data collection capabilities (e.g. additional CCTV and portable vehicle detection). For example, a travel time data collection program can be included as a requirements to facilitate monitoring and management of work zone mobility performance.

Figure 5-6. Crash Data during Project (based on 7-Month Data)

(Source: NCDOT)

Key Aspect #3 - Training

States shall require that personnel involved in the development, design, implementation, operation, inspection and enforcement of work zone related transportation management and traffic control be trained, appropriate to the job decisions each individual is required to make.

Training is an aspect of the Rule that should not differ significantly between design-build and design-bid-build projects. However, since the Contractor may be directly carrying out some responsibilities that it may not typically perform for design-bid-build projects, there may be some additional training needs.

Successes

As discussed previously, the NCDOT Work Zone Qualification and Training Program identifies the qualifications, training requirements, and training resources for the different levels of responsibility of traffic control workers. The Contractors for the AC and AD projects conducted necessary training to satisfy all the requirements of the NCDOT training program.

Issues and Challenges

Applying the Rule to projects can be a major challenge if neither the Agency project team nor Contractor is familiar with the Rule. An issue the NCDOT WZTC group dealt with was recognizing the importance of the Rule within their own Agency. The WZTC group took the initiative to educate NCDOT internally the importance of the Rule so that the appropriate messages were conveyed in specifications and design-build RFPs. The WZTC group recognized that if crucial groups or personnel in the Department did not recognize the significance of the Rule, it hampered NCDOT's ability to develop a good RFP that includes necessary aspects of the Rule. It further limited the Agency's ability to provide guidance and oversight to the Contractor to implement the Rule.

The Contractor's familiarity with the Rule is more critical to work zone safety and mobility in design-build projects because the Contractor bears more responsibilities in work zone management. For example, NCDOT noted that if a design-build team does not have a good understanding of work zone traffic management, it can be difficult for NCDOT to meet the quick turnaround time for reviewing traffic control plans because they may not be well-developed. NCDOT felt that the Contractor did not fully understand the Rule and NCDOT's work zone policy at the beginning of the project, and NCDOT had to regularly provide explanations to the Contractor and sell them on it. It took time for the Contractor to realize the benefits of applying the Rule, but once they did, the response was positive and there was buy-in to its principles. The Contractor realized that more work got done and the project did not suffer setbacks when the work zone was safer and traffic flowed more smoothly.

Key Aspect #4 - Process Review

States shall perform a process review at least every two years. Appropriate personnel who represent the project development stages and the different offices within the State and the FHWA should participate. While this aspect pertains to the agency level, it involves receiving data and feedback from staff on individual projects and doing reviews of a sample of projects.

Contractors will typically have a limited role in an Agency's process review, so the process review is an aspect of the Rule that should not differ significantly between design-build and design-bid-build projects.

Successes

The I-85 Yadkin Corridor Improvement Project underwent frequent reviews and/or audits by FHWA as part of TIGER grant oversight, but had not been the subject of a process review as of the writing of this case study. NCDOT felt that the TIGER reviews and audits of the project had produced good results. They attributed successes with these reviews to a strong scope that specified the requirements and specifications of the project in the RFP. They noted that if a project begins with a solid scope that specifies non-negotiables, performance measures and timelines, many concerns and conflicts can be avoided down the road.

Issues and Challenges

No issues were identified regarding the implementation of this aspect.

Key Aspect #5 - Transportation Management Plan

States are required to develop and implement a TMP for all Federal-aid projects in consultation with appropriate stakeholders.

Successes

One success observed in this project was that the designer and traffic engineering firm on the design-build team worked closely with the construction Contractor throughout the TMP development process. The design team noted that the design-build process involves many iterations of designing then building, then designing, then building, etc., which brings the design team in regular communication and coordination with each other and with the traffic engineers. This collaboration means that issues can often be identified quickly and addressed. All partners involved in the TMP development (include team members on the design-build team and NCDOT) felt they all had ownership in this project. This is a benefit of the design-build process in the development of TMPs. There is not as strong a sense of mutual ownership in a design-bid-build project because the TMP is developed before the Contractor is involved, and any changes in design and implications to TMP development have to be done through supplemental contract amendments.

NCDOT felt that they have a good WZTC process in place for design-build projects compared to some other states. NCDOT staff reviewed all of the WZTC plans, whereas some states use consultants to review the design-build contractor's work. NCDOT indicated there were two benefits for this review process. First, NCDOT's direct involvement in the review process ensures the plans meet NCDOT's standards, requirements, and expectations, whereas the consultant reviewing the plans on behalf of NCDOT may not be as strict or have the same expectation on certain elements. Secondly, having a consultant reviewing the plans on behalf of NCDOT may bring up the concern of a potential conflict of interest in that the reviewing consultant may have business relationship with the design consultant. The reviewing consultant may not deliver a review that serves NCDOT's best interest.

Intelligent transportation systems (ITS) helped with traffic monitoring and information dissemination in the project area. The RFP for each of the projects required that four portable DMS be supplied by the Contractor for traffic control, work zone condition information, and incident management purposes. The RFPs devoted significant score percentages to work zone safety and mobility and encouraged value added elements and innovations. The AD Contractor, as a value added element to improve safety, provided two temporary cameras. These two cameras and the one permanent CCTV camera in the corridor communicated with the NCDOT TMC in Greensboro, which used GPS based speed data and the CCTV cameras to identify and verify incidents and monitor the work zone.

Another success that originated as a challenge involved the incident management plan (IMP). The Yadkin River Bridges are four bridges crossing the Yadkin River in Rowan and Davidson Counties, as illustrated in Figure 5-2. Separated by less than 1,000 feet, the crossings consist of a bridge carrying I-85/US 52, a bridge carrying the Norfolk Southern Railroad, and two bridges carrying US 29/US 70. Because the existing I-85 Bridge has a history of high number of crashes, US 29/US 70 has been used as a detour in the past and was planned as the detour route for this project if incidents were to occur. As part of the AC project, the east of the two US 29/US 70 bridges, which carries northbound traffic, was being replaced. NCDOT had expected that the west bridge (for southbound US 29/US 70) would carry detoured traffic from the I-85 work zone when needed. The west bridge, known as the Wil-Cox Bridge, was built in 1924. In April 2010, NCDOT deemed the Wil-Cox Bridge structurally deficient and closed it to vehicular traffic.

Closing the Wil-Cox Bridge to vehicular traffic posed a challenge to the development of the incident management plan. The plan had to use the east bridge as the detour which would cause major impact on the AC project schedule due to delay in demolition and reconstruction of the east bridge. It was discovered that the east bridge was partially in railroad right-of-way (the railroad bridge was between the existing I-85 Bridge and the east bridge, referred as bridge #3 in Figure 5-2), and NCDOT and the Contractor had to obtain permission from the railroad to begin any work toward demolition and construction of the east bridge. The process of negotiating and dealing with the railroad took several months with the result that the east bridge could not be demolished and reconstructed based on the original schedule, and therefore it was available to serve as the I-85 detour route. Because it was a design-build project, the Contractor was able to rearrange and devote resources to other activities of the project without experiencing major impacts on project schedule. Making these changes on a design-bid-build project would likely be more complicated, involving Agency re-design work and amendments to the contract, and could increase the duration of the project and associated safety and mobility impacts.

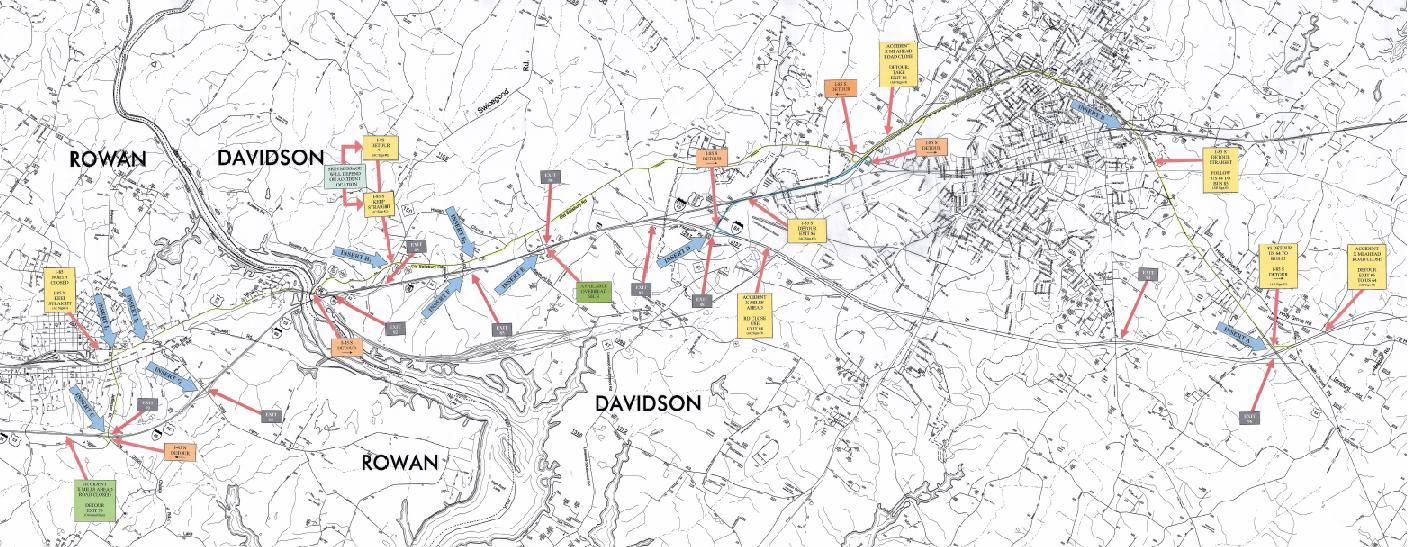

In addition, a new coordinated effort led to a much wider plan for incident management. The design-build teams created an incident management plan (part of which is shown in Figure 5-7) with shielded signs installed both on and off the project area. During incidents the shields would be removed, and the 4 DMS (required in both projects RFPs) would be activated with prescribed messages. This additional effort was not part of the RFP, but came into play after several incident management meetings. Both design-build teams created this plan with NCDOT and did not receive any additional compensation. All parties acknowledged that supplementing the plan and enhancing the safety and mobility of the project area benefits everyone - workers, motorists, and the overall project. Similar to the success with developing the TMP described earlier, this demonstrates a unique benefit of design-build projects due to a sense of mutual ownership to projects and an understanding of the importance of coordination and cooperation among all parties involved.

Figure 5-7. Supplemental Incident Management Plan

(Source: NCDOT)

As part of the incident management effort, law enforcement attended to anyone who pulled over or experienced a break down in the project area. When necessary, law enforcement would notify a rotation of towing companies to remove vehicles from the construction area. This eliminated the need for a Contractor supplied courtesy patrol or dedicated towing operation. NCDOT also had its IMAP (Incident Management Assistance Patrols) trucks patrolling the area. Usually only active on weekdays, NCDOT added a weekend IMAP presence during the duration of the AC and AD projects. The presence of IMAP and tow trucks reduced response time and the duration a stopped vehicle is in the work zone.

The project managers for each design-build team indicated that there were safety policies in place, and for the most part, were required by the Occupational Safety and health Administration (OSHA) and pertaining laws. There were two full-time safety managers for the AC project and one full-time safety manager for the AD project. Both Contractors extended the idea that everybody on the project is responsible for safety and should look out for safety of their own, their co-workers, and the traveling public. The incentive for the Contractor is the job is completed quicker and the duration of the work zones gets shortened with improved safety and mobility. That benefits all parties.

The RFP for the project allowed for 30-minute closures of I-85 for certain construction operations including girder installation or removal and traffic shifts. These closures were allowed from midnight to 6:00 am, and at the end of the 30-minute period, the closure was to be reopened until the queue was depleted. Upon depletion of the queue, another 30-minute closure could be put in place. In one case for the AC project, there were to be several nights over a period of a week where these types of closures were to be used. The Contractor came to NCDOT and proposed a full closure of the Interstate, using frontage roads and other minor roads in the area for a detour. The Contractor developed this proposal during the project, and the proposed detour route was not in the TMP. The Contractor previewed the detour route, evaluated the pavement condition, proposed using law enforcement rather than flaggers for directing traffic through the detour route, and agreed to maintain the pavement on the detour route between and after the closures. There was a great deal of pre-planning and coordination between NCDOT and the Contractor, including notifying commercial vehicles in the Charlotte and Triad areas to reroute to I-77 and I-40.

During the closures the Contractor drove the detour route, checking on traffic flow and to see if the pavement was holding up with the increased traffic. The end result was considered a success by both the Contractor and NCDOT. They thought that the use of law enforcement (compensated by the Contractor) and their blue lights was more effective than flaggers; the detour route provided a much safer alternative than intermittent closures; and vehicular mobility was better with the full closure and detour than what was originally planned. One of the most evident benefits of using the full closure and detour route was worker safety, and the fact that the operations were performed without any interference of traffic, and there was no interaction between motorists and construction workers and their equipment.

An example of the Contractor's attention to safety was pointed out by the Resident Engineer of the AC project. During the construction of a new bridge, the barrier on the edge of the bridge had been installed. Because the bridge was not open to the public there were no pedestrian facilities and the railing had not yet been installed. However, to enhance the safety of the workers on the bridge, the Contractor installed a temporary railing on the bridge, as shown in Figure 5-8. On a design-bid-build project, NCDOT would have had to prepare a change order so that the Contractor would get paid for the extra work. In a design-build project, where the Contractor is not getting paid using the same unit price method, a Contractor is more likely to add things or make enhancements that are not in the plans for the benefit of worker safety.

Figure 5-8. Temporary Bridge Railing

(Source: URS Group, Inc.)

Issues and Challenges

NCDOT found that with the fast moving nature of design-build projects, if an issue is identified with the implementation of the TMP or a specific traffic control element, by the time the information has gone through the correct channels and been conveyed to the Contractor, the work in that area may have been completed and the work zone changed/removed. Another situation could be that the Contractor receives notification of the issue from the Agency but does not address it until the work zone is removed or altered for a new stage. NCDOT felt that a remedy of this situation could be to include provisions in the RFP stating that WZTC issues must be addressed in a specific time frame and damages are assessed if it does not get addressed in that time. Documentation in writing (memorandum and/or email) is extremely valuable. The Contractor is more likely to give attention to comments and take corrective action when there is written documentation of the concerns.

The RFP for each of the projects required that four portable DMS be supplied for use on the corridor and for incident management purposes. The RFP specified that the DMS be supplied by the Contractor and that their function be controlled remotely by NCDOT TMCs. However, the RFP did not include requirements to ensure the signs were compatible with the existing NCDOT communications systems and infrastructure. This resulted in difficulties with communicating and controlling the DMS in the beginning of the project. NCDOT felt that this was one area where more detailed requirements would be beneficial.

The ITS devices (CCTV cameras and DMS) were initially controlled by two different TMCs. The Metrolina TMC in Charlotte (about 40 miles south of the project) controlled the ITS devices in the southern segment (AD project) and the Piedmont Triad TMC in Greensboro controlled the devices in the northern segment (AC project). Due to lack of CCTV cameras in the southern segment and the distance to the project area, the Metrolina TMC was not in the best position to clearly know the traffic and work zone conditions in the project area and post DMS messages in response to conditions. Eventually, the Piedmont Triad TMC was given full control with the exception of the Metrolina TMC controlling the DMS and cameras when special events (NFL, NASCAR, etc.) occurred in the Charlotte area.

Key Aspect #6 - PS&E Shall Include TMP or Provisions for Contractors to Create a TMP

A TMP will be created and provided by the State or Agency, or the Contractor will develop it subject to the approval of the State prior to implementation.

Successes

One of the major changes of the new NCDOT 2012 Standard Specifications is that it added the requirements of the Work Zone Safety and Mobility Rule. It defines the components of the TMP. The first paragraph of the Work Zone Traffic Control General Requirements section of the Standard Specification now reads:

Maintain traffic through work zones in accordance with these Specifications, the MUTCD, Roadway Standard Drawings, 23 CFR 630 Subparts J and K and the Transportation Management Plan (TMP)

Each of the RFPs outlined the design parameters and requirements of the TMP. NCDOT noted that it is important to be specific about requirements without being prescriptive. For example, one of the components of the design parameters referenced subpart 23 CFR Subpart K (FHWA's Temporary Traffic Control Devices Rule). NCDOT does not specify barrier, drums, or cones like it would in a design-bid-build project, but specifies that the Contractor must follow the AASHTO Roadside Design Guide, and requires the Contractor to perform an engineering study to assess the need for barrier as part of their proposal. Other design parameters were lane and shoulder width, the minimum number of lanes to be kept open, minimum speed limits, etc.

The Contractors were able to work several value-added elements into their proposals, including:

- Self-imposed phases of completion with liquidated damages fixed to those dates.

- In the RFP the AD project was to be completed no later than 10/31/13. The winning contractor team identified substantial completion for 4/30/13 and final acceptance for 5/30/13. Liquidated damages for missing these dates were $2,000 per day.

- Longer and more significant warranties than required in the RFP, which added value - four additional years for the AD project.

- Minimization of the number of traffic shifts.

- Specific to the AD project (northern segment)

- Maintain 12' lanes (RFP allowed reducing to 11' lanes).

- Maintain 8' shoulders.

- Provide two temporary portable closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras.

- Provide an extra loop ramp at the NC 150 interchange.

- Building ramps from the closed Clark Road interchange to transport material across the roadway. This reduced the travel of project related vehicles on the Interstate by about 10,000 trips over the course of the project.

The RFPs for both projects included a section pertaining to cooperation between the Contractors of both projects. This section required coordination meetings between the two design-build teams and NCDOT, and stated that there was to be coordination to maintain safe traffic operation and pavement markings at all times during construction. Additionally, the RFPs stated that there would be no additional contract time or compensation for failure to coordinate schedules.

Personnel from both projects and NCDOT staff said that the cooperation between the two projects began shortly after the contract for the AD project was executed. Getting everybody together from the beginning was beneficial for both projects and for NCDOT, as the Contractors were able to share information and coordinate closures, lane shifts, and schedules for work that occurred in the area where the two segments bordered. An example of cooperation between the two projects was the innovative use of the Clark Road Bridge. The Clark Road Bridge was a part of the Clark Road Interchange, and the Interchange was to be removed in the AC project once all the ramps and the Clark Road Bridge were closed. The AC Contractor used the inactive bridge for moving materials and equipment from one side of the Interstate to the other. Due to early coordination between the two Contractors, the AC Contractor was aware that the AD Contractor would also benefit from using the bridge for moving materials and equipment. The AC Contractor left the Clark Bridge in place after they no longer needed it so that the AD Contractor could use it for movement of materials and equipment as well. The result of this cooperation was a significant reduction in the number of construction vehicles traveling through traffic lanes in the work zone. The effect of this cooperative and innovative agreement was a less congested, safer work zone. This solution also led to a significant reduction in construction time and cost.

Issues and Challenges

NCDOT felt that an important mechanism for ensuring that safety and mobility receive the necessary attention during scoping, RFP development, and proposal evaluation of design-build projects is to include WZTC personnel in each stage of the project development. WZTC personnel can help ensure that the work zone safety and traffic control elements of the technical requirements are updated and improved based on lessons learned from past projects and the appropriate level of scoring is attached to safety and mobility in the proposal evaluation criteria. It is also valuable to have WZTC staff on the evaluation and selection committee to ensure that safety and mobility factors are adequately considered and weighed in the proposal evaluation process.

While this was not an issue for the I-85 Corridor Improvement Project, NCDOT stressed the importance of having a qualified designer/traffic engineering firm on the design-build team and establishing good quality management policies and processes to produce quality work zone and traffic control plans. This is particularly important for a design-build project such as the I-85 project, as NCDOT had a very limited window (10 days) for reviewing the plans. It is possible that the winning design-build team has a well-qualified general contractor who teams up with a design firm or a traffic engineering firm who may not have the same level of qualifications and experience in developing work zone and traffic control plans. It is a challenge to the Agency to establish scoring criteria and a selection process for design-build projects to ensure the winning team has appropriate qualifications in all areas.

Key Aspect #7 - Pay Item Provisions - Method or Performance Based

For method-based specifications, individual pay items, lump sum payment, or a combination thereof may be used. For performance-based specifications, applicable performance criteria and standards may be used.

Successes

The RFPs for each of the two projects list several different intermediate contract times (ICT), which identify time restrictions for when specific lanes and ramps can be narrowed or closed during given time periods; weekdays, weekends, special events, etc. For each ICT there are liquidated damages identified for lane narrowing or closures during the restricted time periods.

The AC project has three different ICTs with liquidated damages including:

- $10,000 per hour for lane narrowing, closure, and special event and holiday restrictions for I-85 and all ramps.

- $5,000 per 15-minutes for road closure time restrictions for I-85 and all ramps.

- $4,000 per day for ramp closures at the NC150 interchange during restricted times.

The AD project has five different ICTs with liquidated damages:

- $5,000 per 30-minutes for lane narrowing, closure and special event and holiday restrictions for I-85, I-85 Business and all ramps.

- $500 per 30-minutes for lane narrowing, closure, and special event and holiday restrictions for Belmont Road.

- $2,500 per 15-minutes for road closure time restrictions for I-85 and all ramps.

- $500 per 15-minutes for road closure time restrictions on all other minor roads.

- $2,500 per 15-minutes for continuous weekend road closure restrictions for I-85 Business ramps.

The different levels of liquidated damages provide some flexibility to the Contractor. The Contractor was able to weigh the benefits of keeping a closure for a given time over the limit against the costs they would incur. Often the benefit/cost of having a little more time to finish a task now was greater than stopping and completing the task later with a new traffic control installation. The AD Contractor noted that it was beneficial to have the liquidated damages broken down to 15 and 30-minute periods instead of by hour increments. While it does create a short-term inconvenience to motorists, extending a lane closure to complete work can be a safer and less disruptive alternative than having to remove the closure prior to finishing work and then having to install the same closure again later. This often helped shorten the overall lane closure duration and reduce impacts to work zone safety and mobility.

Issues and Challenges

One of the Contractors expressed some frustration with the manner in which the payment for the project was made. NCDOT handled design-build project payments in the same manner as they did design-bid-build projects, which was by tracking amount of materials used, moved, built, etc. The monthly payment for MOT was based on the total amount estimated for traffic control, divided by the total months the project would take. The Contractor was initially anticipating being paid based on schedule and progress, not by materials used.

Key Aspect #8 - Designated Trained Person

The State and the Contractor shall each designate a trained person at the project level who has the primary responsibility and sufficient authority for implementing the TMP and other safety and mobility aspects of the project.

Successes

The RFP for both projects require a Traffic Control Supervisor (TCS) who is knowledgeable of TCP design and application and has full authority of the maintenance of traffic. That person was required to have a minimum of 24 months of on the job training, and be certified by either the Contractor or NCDOT that they were qualified to perform all duties.

NCDOT felt that traffic control for one of the projects segments was very successful because the TCS had extensive knowledge and experience and fully understood NCDOT's expectations. The TCS for that segment had a great deal of experience with work zones in the state of North Carolina, and his knowledge and familiarity of local processes proved to be an important success for the project. This is not necessarily unique to design-build projects; however, since the Contractor has more responsibility for preparing and implementing the traffic control on design-build projects, a solid TCS can be particularly helpful when this project delivery method is used.

Issues and Challenges

Because of the nature of these two projects being adjacent to each other, NCDOT and both Contractors acknowledged that there could be difficulties with traffic control activities in the area where the projects border. There was an instance where each Contractor had plans to close different lanes of the roadway in the common area at the same time. This issue was resolved by getting the designated TCS from each project working together with NCDOT. This experience actually improved coordination between the two projects for future traffic control activities.

previous | next