Regional ITS Architecture Guidance Document

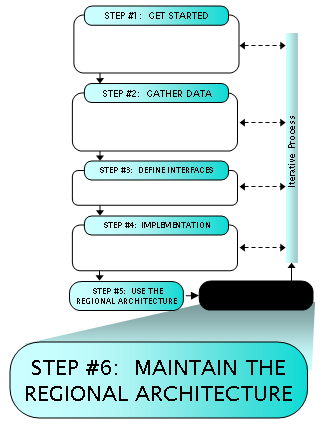

This section discusses various options and considerations associated with on-going maintenance of the architecture products. This includes detailing the responsibilities and procedures that need to be considered as an architecture is used and maintained over time. The regional ITS architecture is not a static set of outputs. It must change as plans change, ITS projects are implemented, and the ITS needs and services evolve in the region.

Much as ITS systems require planning for operations and maintenance, a plan should be put in place during the original development of the regional ITS architecture to keep it up to date.

|

|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

|

PROCESS Key Activities |

Define Project Sequence

|

|

INPUT Sources of Information |

|

|

OUTPUT Results of Process |

|

The regional ITS architecture is described by a set of outputs discussed in Sections 3 through 6 of this document. These sections have suggested a process for creating the original set of outputs that represent the regional ITS architecture. This section will examine the process of maintaining the architecture. This process is really one of continual improvement and evolving with the region as its stakeholders make use of the architecture and a region's needs grow and change, guided by the principles of Configuration Control and Change Management. Some of the key aspects of the process, which are covered in more detail below are:

The development of an architecture maintenance plan

and the implementation of a program to maintain the architecture is also a

requirement of the ITS Architecture and Standards Final Rule/ Final Policy,

which says: "The agencies and other stakeholders participating in the

development of the regional ITS architecture shall develop and implement

procedures and responsibilities for maintaining it, as needs evolve within the

region."

The development of an architecture maintenance plan

and the implementation of a program to maintain the architecture is also a

requirement of the ITS Architecture and Standards Final Rule/ Final Policy,

which says: "The agencies and other stakeholders participating in the

development of the regional ITS architecture shall develop and implement

procedures and responsibilities for maintaining it, as needs evolve within the

region."

As ITS projects are implemented, the regional ITS architecture will need to be updated to reflect new ITS priorities and strategies that emerge through the transportation planning process, to account for expansion in ITS scope, and to allow for the evolution and incorporation of new ideas. A maintenance process should be detailed for the region, and used to update the regional ITS architecture. This maintenance process should be documented as part of the initial development of the regional ITS architecture in a regional ITS architecture maintenance plan. The goal of the maintenance plan is to guide controlled updates to the regional ITS architecture baseline so that it continues to accurately reflect the region's existing ITS capabilities and future plans.

Note that the process of architecture maintenance covered in this white paper is meant to apply to a wide range of regional and statewide ITS architecture developments. Each architecture development effort will need to tailor the process to meet the needs and resources of their particular region.

The regional ITS architecture is not static. It must change as plans change, ITS projects are implemented, and the ITS needs and services evolve in the region. The regional ITS architecture must be maintained so that it continues to reflect the current and planned ITS systems, interconnections, and other aspects of architecture. The following list includes many of the events that may cause change to a regional ITS architecture:

The National ITS Architecture and Turbo Architecture are not updated on a set schedule but on the basis of the program's configuration control process that reviews and analyzes stakeholder inputs and works with US DOT to schedule when the updates should be incorporated. Updates to the National ITS Architecture and Turbo will be publicized on the ITS Joint Program Office (JPO) Architecture web site: http://www.its.dot.gov/arch/index.htm.

There are several changes relating to project definition that will cause the need for updates to the regional ITS architecture.

The above reasons for possible changes in the regional ITS architecture baseline may happen frequently or infrequently, depending upon the region and the specifics of the original regional ITS architecture development effort. This should be taken into account as one set of factors in determining how often to update the regional ITS architecture.

The purpose of maintaining a regional ITS architecture is to keep it current and relevant, so that stakeholders will use it as a technical and institutional reference when developing specific ITS project plans. A key characteristic of a successful regional ITS architecture is consensus; that is, the notion that each stakeholder has and continues to buy-in to the architecture as the model for how ITS elements have been deployed in a region, and more importantly how future ITS elements should be deployed in the region.

Each of the maintenance decisions discussed in this section are primarily in support of keeping the regional ITS architecture relevant to the ITS planning and deployment of ITS projects as resources become available. As conditions in a region naturally evolve, an effective regional ITS architecture maintenance process will also evolve the regional ITS architecture so that it "keeps up" with the evolving conditions, and maintains the characteristic consensus that ensures stakeholders will find it relevant and a benefit to use.

The decisions that will be discussed are:

Who will maintain the Regional ITS Architecture? This is perhaps one of the most crucial maintenance decisions for a regional ITS architecture. To maintain a consensus regional ITS architecture, to some extent all stakeholders will need to participate, but typically one or two agencies will take the lead responsibility to maintain the regional ITS architecture.

An important concept is that the responsibility for architecture

maintenance should not be delegated to an individual person, but should instead

be assigned to an agency or institutional group in the region.

An important concept is that the responsibility for architecture

maintenance should not be delegated to an individual person, but should instead

be assigned to an agency or institutional group in the region.

Often an individual may be, or may have been, a champion in the development of a regional ITS architecture, and that's fine. But maintenance is recurring, and necessarily is a long-term effort. The responsibility may be delegated to an individual at any given time, but the overall responsibility should be a stated role of an institution or agency in the region. In this way the responsibility transcends the variabilities that can impact an individual person's activities and career. Sometimes this responsibility will be shared by agencies. This is the case with the Inland Empire maintenance plan from California (see Appendix C.3.1) that provides for the maintenance responsibility to be assumed jointly by four key agencies in the region.

Issues in determining maintainer

Two key considerations in selecting a maintainer are described below.

Maintaining a regional ITS architecture utilizes a range of skills. In order to properly evaluate changes to the architecture the maintainer must have staff that is knowledgeable of the existing regional ITS architecture. This implies a detailed technical understanding of the various parts of the architecture and how changes would affect each part. Also required is an understanding of transportation systems in the region (although this understanding can reside jointly in the group of agencies/ stakeholders who participate in the maintenance process). Finally, the maintainer agency needs to have staff with an understanding of the tools used to create (and to update) the architecture. This might include for example, knowledge of the Turbo Architecture tool, if that is used to hold some of the architecture information. The agency responsible for maintaining the architecture needs to have the skills within its own organization or consider acquiring the skills. In either case, the agency needs the necessary funding to support the maintenance effort.

Having the resources to maintain a regional ITS architecture may mean that the stakeholders using the regional ITS architecture have to share in the costs to acquire these resources, even though one specific agency may commit to maintain staff or contract the skill set necessary.

The agency that maintains a regional ITS architecture ideally is one that has broad functional responsibilities across the full scope of the regional ITS architecture. In this case, "scope" represents the geographic area of the region, the transportation functions in the region, and the timeframe for deployment of new ITS elements and interfaces in the region.

A natural maintainer for many regions is the Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO). Very often the scope of the MPO will match (or nearly match) the scope of the regional ITS architecture. This is the case in the Northeastern Illinois maintenance plan—the responsible agency for maintenance is the MPO in the region (CATS). This is also true for the Oahu Regional ITS Architecture, where Oahu Metropolitan Planning Organization will assume the maintenance responsibility. Both of these plans can be found in Appendix C. In cases where the MPO does not possess the resources to manage the effort, or in cases where there is no MPO (e.g. if the region is rural in nature) alternate maintainers might be identified. Some other possibilities for maintainer organizations are:

When one agency or institution takes responsibility for architecture maintenance, they may use agreements to create a management or oversight function (e.g. a "regional ITS architecture maintenance committee" or "regional ITS architecture maintenance board") to oversee regional ITS architecture maintenance work, which would have representation from the key stakeholders to the agreement. This group might be given management authority over the maintenance process. In this way, the stakeholders are investing in and controlling their own regional ITS architecture, and they will have direct responsibility for the quality of the product.

What group will assist the maintainer in evaluating and approving changes?

Another decision that must be made is who will support the maintainer in evaluating and approving changes to the architecture. This should be a group of representatives of key stakeholders, ideally members from the areas of traffic, transit, public safety, and maintenance. This group might be a carryover from a committee or body that consisted of key stakeholders in the development of the architecture, or it could be a newly constituted group, or it might be a form of the Regional ITS Committee described above. These groups have many names, but one common trait — they often include both technical and managerial representatives of the key transportation agencies in the region. As an example, the Inland Empire maintenance plan calls out the creation of a new group—the Architecture Maintenance Team—with representation from key stakeholders. The Oahu Regional ITS Architecture Report calls out an existing group— the ad hoc ITS Technical Task Force—to support the maintenance activity.

The group responsible for evaluating and approving changes to the architecture may be a group that has some coordinating authority for integration of systems in the region. However there is no need for the group to have legal or contracting authority. They will be serving as a vehicle for consensus.

Another way to describe when the architecture will be updated is to consider what "timetable" will be used for making updates or changes to the architecture. There is no set timetable that will apply to every region. The timetable chosen will depend on several factors including how the regional ITS architecture is used and the funding/ staffing available for the task.

How often will the regional ITS architecture be modified or updated? There are two basic approaches to update interval: periodic maintenance and exception maintenance. Each has their advantages and disadvantages. They are not mutually exclusive, and an approach could be developed that is a combination of the two basic models.

Note, the above discussion relates to "how often" the architecture is updated. A complementary discussion regarding whether the update involves incremental changes or is an update of the full baseline will be provided in section 4.2.

What aspects of the regional ITS architecture will be maintained? Those constituent parts of a regional ITS architecture that will be maintained are referred to as the "baseline". This section will consider the different "parts" of the regional ITS architecture and whether they should be a part of the baseline.

One of the benefits of a regional ITS architecture is to enable the efficient exchange of information between ITS elements in a region and with elements outside the region. Efficiency refers to the economical deployment of ITS elements and their interfaces. The result of these ITS deployments should be contributions to the safe and efficient operation of the surface transportation network. Each of the components in the regional ITS architecture below have a role in this economy, and appropriate effort should be levied to maintain them.

Description of Region

This description includes the geographic scope, functional scope and architecture timeframe, and helps frame each of the following parts of a regional ITS architecture. Geographic scope defines the ITS elements that are "in" the region, although additional ITS elements outside the region may be necessary to describe if they communicate ITS information to elements inside the region. Functional scope defines which services are included in a regional ITS architecture. Architecture timeframe is the distance (in years) into the future that the regional ITS architecture will consider. The description of the region is usually contained in an architecture document, but may reside in a database containing aspects of the regional ITS architecture, and should certainly be a part of the baseline.

List of Stakeholders

Stakeholders are key to the definition of the architecture. Within a region they may consolidate or separate, and such changes should be reflected in the architecture. Furthermore, stakeholders that have not been engaged in the past might be approached through outreach to be sure that the regional ITS architecture represents their ITS requirements as well. The stakeholders should be described in architecture documentation (and may also reside in a database representing aspects of the regional ITS architecture). Their listing and description should be part of the baseline.

Operational Concept

It is crucial that the operational concepts (which might be represented as roles and responsibilities or as customized market packages) in a regional ITS architecture accurately represent the consensus vision of how the stakeholders want their ITS to operate for the benefit of surface transportation users. These should be reviewed, and if necessary, changed to represent both what has been deployed (which may have been shown as "planned" in the earlier version of the regional ITS architecture) and so that they represent the current consensus view of the stakeholders. Many of the remaining maintenance efforts will depend on the outcome of the changes made here. The operational concept will reside in the architecture documentation (and possibly in a diagramming tool if a customized market package approach is used) and should be part of the baseline.

List of ITS Elements

The inventory of ITS elements is a key aspect of the regional ITS architecture. Changes in stakeholders as well as operational concepts may impact the inventory of ITS elements. Furthermore, recent implementation of ITS elements may change their individual status (e.g. from planned to existing). The list of elements is often contained in architecture documentation, and is key information in any architecture database. It is a key aspect of the baseline.

List of Agreements

One of the greatest values of a regional ITS architecture is to identify where information will cross an agency boundary, which may indicate a need for an agency agreement. An update to the list of agreements can follow the update to the Operational Concept and/or interfaces between elements. The list of agreements will usually be found in the architecture documentation. This listing should be a part of the baseline.

Interfaces between Elements (interconnects and information flows)

Interfaces between elements define the "details" of the architecture. They are the detailed description of how the various ITS systems are or will be integrated throughout the timeframe of the architecture. These details are usually held in an architecture database. They are a key aspect of the architecture baseline, and one that will likely see the greatest amount of change during the maintenance process.

System Functional Requirements

High-level functions are allocated to ITS elements as part of the regional ITS architecture. These can serve as a starting point for the functional definition of projects that map to portions of the regional ITS architecture. Because of the level of detail, these are usually held in spreadsheets or databases, but may be included in the architecture document. They are a part of the baseline.

Applicable ITS Standards

The selection of standards depends on the information exchange requirements. As projects are implemented and standards are chosen for a project they need to be reflected back in the regional ITS architecture so that other projects can benefit from the selections made. In addition, the maintenance process should consider how ITS standards may have evolved and matured since the last update, and consider how any change in the "standards environment" may impact previous regional standards choices (especially where competing standards exist). For example, if XML based Center-To-Center standards reach a high level of maturity, reliability and cost-effectiveness, then a regional standards technology decision may be made to transition from investments in other standards technologies (e.g. CORBA to XML). The description of the standards environment for the region, as well as the details of which standards apply to the architecture should be part of the baseline.

Project Sequencing

While project sequencing is partly determined by functional dependencies (e.g. "surveillance" must be a precursor to "traffic management"), the reality is that for the most part project sequences are local policy decisions. Project sequences should be reviewed to make sure that they are in line with current policy decisions. Furthermore, policy makers should be informed of the sequences, and their input should be sought to make the project sequences in line with their expectations. This is crucial to avoiding the regional ITS architecture becoming irrelevant. The project sequencing should be included in the architecture documentation and may also be held in a spreadsheet or database. These should be part of the architecture baseline.

In addition to the components of the architecture being

maintained above, it is also important to document the resources that were used

along the way to develop the architecture — the Region's Transportation Plan,

TIP, ITS Strategic Plans, various studies, as well as other regional ITS

architecture. Document these other resources — their titles, dates or

versions, and where they can be found so that future maintainers can understand

some of the background that supported the development of this regional ITS

architecture and remember that changes to those documents may affect the

architecture.

In addition to the components of the architecture being

maintained above, it is also important to document the resources that were used

along the way to develop the architecture — the Region's Transportation Plan,

TIP, ITS Strategic Plans, various studies, as well as other regional ITS

architecture. Document these other resources — their titles, dates or

versions, and where they can be found so that future maintainers can understand

some of the background that supported the development of this regional ITS

architecture and remember that changes to those documents may affect the

architecture.

This section describes the regional ITS architecture maintenance process. The process described below is based upon the more general discipline of Configuration Management. This section will first present a short summary of configuration management, and then describe the process of maintaining a regional ITS architecture, drawing connections between the general discipline and the specific application of it for maintaining a regional ITS architecture. The maintenance process described in this section is a suggested or example process for the maintenance of regional ITS architecture. The process presented can be applied to the maintenance of any regional ITS architecture, but should be tailored to fit the size and scope of the particular architecture. The process should also be tailored so that it fits within the region's transportation planning processes (e.g., the Regional Transportation Plan update process).

Configuration management is defined as: "A management process for establishing and maintaining consistency of a product's performance, functional, and physical attributes with its requirements, design and operational information throughout its life" and can be applied to the development of any system. In the context of regional ITS architecture it is a process for establishing and maintaining consistency of the architecture's information content throughout its life. In general, the configuration management process consists of five major activities:

These activities are performed throughout the life of the development and operation of systems.

There are some additional resources that

provide more detail and some specific tools and techniques for implementation

of configuration management. These may provide additional information in

adapting the information presented here to address specific regional needs.

There are some additional resources that

provide more detail and some specific tools and techniques for implementation

of configuration management. These may provide additional information in

adapting the information presented here to address specific regional needs.

The process of maintaining a regional ITS architecture involves managing change, and can be described using the activities summarized in the previous discussion of configuration management.

CM Planning

Before the maintenance activity begins the parameters of the activity must be identified and the details of the process must be determined. These parameters, defining who will maintain the architecture, when the architecture will be updated, and what will be the baseline maintained have been described in Section 8.2. These decisions and the maintenance process itself should be defined in an architecture maintenance plan, which is the primary output of the configuration management planning activity. The maintenance plan may be a separate document or part of the larger regional ITS architecture document. The plan should be created during the initial development of the regional ITS architecture. If it was not then the process should be defined and documented as soon as possible. The maintenance plan should also be a part of the architecture baseline described below.

Who

The maintenance plan should identify who will be responsible for the maintenance effort and what group of stakeholders will review and approve changes to the architecture baseline. In addition to defining who will be involved in maintenance a description of each agencies roles and responsibilities may be included. The Oahu Regional ITS Architecture Report provides just such details on roles and responsibilities.

When

The maintenance plan should also identify the timetable for regional ITS architecture updates. As discussed in 8.2.2, there are several options for this timeline. The other timing decision that should be identified in the maintenance plan is when to set the baseline and begin the maintenance process. In the case of regional ITS architectures, the first release of the architecture after its initial development would normally constitute the initial baseline. This is the point at which the architecture is ready for distribution and use, and the point at which potential changes to the architecture may begin to develop.

What

The maintenance plan should clearly identify what will be maintained- i.e. the architecture baseline. Section 8.2.3 discussed the parts of the regional ITS architecture that should be maintained. In fact, these parts are contained in databases (e.g. a Turbo Architecture database), spreadsheets, drawing files (e.g. PowerPoint or Visio), Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) files for a web site, and documents. Defining the architecture baseline is defining exactly what documents, databases, etc. will be maintained.

In addition to these architecture outputs, source documents that were used to produce the regional ITS architecture outputs may also be important to identify. Some of these documents will be the subject of later revision and maintaining a consistency between the architecture and the other efforts is important. For example, if the regional ITS architecture inventory was derived from a number of individual stakeholder inventory documents, then the date and version numbers of those source documents should be considered for inclusion in your list of controlled items. Other examples of these source documents might include early deployment study reports, strategic deployment plans, and inventory tracking reports. It is important that the dates of reports and any version numbers associated with the reports are recorded as part of the configuration that is controlled. This way, subsequent releases of these documents would trigger an analysis to determine how the changes are best propagated through the rest of the controlled items in order to maintain a consistent configuration. It's also necessary to record where these are stored — at which agency, on which data server, web site or other storage location.

The versions of software tools that were used to produce the architecture might also be included in the set of configuration items. These might include the Turbo Architecture software and the version of the National ITS Architecture used. For these tools, the important thing to record as part of the configuration is the version number and date of release. Subsequent updates to the tools and databases would trigger a change analysis.

A final consideration that goes into the definition of the architecture baseline is how you plan to use the architecture. Will market package diagrams be an important source of interfaces for project definition? Or will interconnect diagrams be used? Or will project developers go directly to the database representation for their detailed definition? Considering some of these alternatives will help you decide which representations of the architecture are most important to your region.

Table 17 shows some examples of the items that might be selected for the architecture baseline.

Table 17. Examples of Configuration Items to Consider

| Turbo Architecture Databases | Planning Documents |

| Regional ITS Architecture Documentation | Inventory Tracking Documents |

| Maintenance Plan (if a separate document) | Turbo Architecture Software Version |

| List of documents used in developing architecture or with which the architecture should be consistent: | National ITS Architecture Version |

The definition of baseline will depend greatly on the scope and complexity of the regional ITS architecture effort. For small efforts the baseline might consist of only a database, an architecture summary document (which would include the maintenance plan) and the version of National ITS Architecture (and possibly Turbo Architecture) used for the development.

How

Once the Who, When, and What are established, deciding how to change the baseline needs to be considered. Change is inevitable. The goal of configuration management is not to keep changes from occurring, but to permit changes in a controlled fashion, ensuring that all configuration items are consistent with their descriptions at all times. Due to the nature of a regional ITS architecture (i.e. a set of documentation and databases rather than an actual system of software and hardware), there are two basic approaches that could be taken to updating the baseline. The first is incremental change based upon individual change requests. The second is a full baseline update based upon a periodic revisiting of the entire architecture. In the latter case all the architecture outputs are revisited and modified based upon stakeholder inputs, using much the same process as was used in the original development of the architecture.

The process of changing the baseline can be broken into the steps shown in Figure 56. The following sections will consider each process step as it might be applied to both approaches to architecture maintenance. The formality or amount of effort that goes into these process steps will depend upon the scope and complexity of the regional ITS architecture.

Figure 56. Process for Change Identification

Each architecture effort will need to make a decision about who can initiate a change request. In some areas the selected answer will be "anyone". This approach is called out in the Inland Empire maintenance plan. Allowing anyone to initiate a change is conducive to the development of a "consensus" architecture because it empowers all stakeholders to provide inputs. However the approach does have a drawback — if literally anyone can input requests the region runs the risk of being overrun by requests that will tax scarce resources to review and decide upon proposed changes. An alternative approach that may be attractive to some larger regions is to limit who can make change requests to members of the maintenance committee/board or members of other key ITS committees. This effectively means that any change suggested has the approval of a key stakeholder. This approach is planned in the Northeastern Illinois maintenance plan. This has the added benefit of spreading the resources needed to generate or evaluate changes among the group.

The plan might also address when a change request should be made. For example, the Oahu maintenance plan lays out detailed directions for inclusion of ITS projects in the TIP, identifying when changes to the regional ITS architecture need to be made in order for a project to be funded through the TIP. Also the plan might identify the types of changes that will be made to the architecture. The Oahu plan identifies administrative amendments that do not require Policy Committee approval and non-administrative amendments that do require Policy Committee approval.

It is recommended that a simple change request form be created that contains at least the following information:

As part of the configuration management process this information should be maintained in a change log (or change database) that would add the following additional fields of information

There are many ways the above change forms can be

implemented. The form could be on a regional architecture website for download

by anyone submitting a change. A less formal alternative would be for a change

request to be submitted as an email containing the key information above. The

formality in the process creates an audit trail of all changes considered as

well as a record of those approved, those rejected, and those deferred. This

audit trail can come in handy in future assessments of proposed enhancements or

changes to the systems.

There are many ways the above change forms can be

implemented. The form could be on a regional architecture website for download

by anyone submitting a change. A less formal alternative would be for a change

request to be submitted as an email containing the key information above. The

formality in the process creates an audit trail of all changes considered as

well as a record of those approved, those rejected, and those deferred. This

audit trail can come in handy in future assessments of proposed enhancements or

changes to the systems.

The above description of initiating changes applies to individual change suggestions that might arise from review of the architecture by a stakeholder or from the impact of individual projects. In the case of a full baseline update of the regional ITS architecture, this could be handled by a summary change request indicating the nature of the update and referencing the stakeholder interactions that will generate a set of changes.

Configuration Management Resources

What resources are needed to perform configuration management? In the context of maintenance of a regional ITS architecture, the same personnel skills that are used to work with the National ITS Architecture and possibly the Turbo architecture tool will be used in managing the configuration items that are included in the configuration management plan. In addition to human resources, there will be the need to have file servers, web sites, or other central locations to store electronic copies of configuration items. These must be "read-only" and protected so that changes are not made to released versions of the databases and documents. Any required changes require a new version number/date and hence a new copy of the configuration item separate from the previous version.

Configuration Identification

Each configuration item must have a unique identifier associated with it. The identifier for the item should be marked on it in some fashion, so that the item can be identified without error and tracked. In the context of regional ITS architecture maintenance, this can be accomplished by suffixing a version number and date in the file name for a database file or electronic document, or it can be physically marked on a printed document. The identifier can also be included in a header or footer for documents and diagrams. In this way, everyone who reads the materials or looks at the database (using Turbo Architecture, for example) will know which version they are reviewing.

It also makes sense to have a controlled document that lists all of the configuration items and the versions that constitute that baseline in time. Maintenance history can also be included. Any interdependencies between the items are worth recording. There are several reasons for this. First, you want to be able to know what items you have under configuration control and be able to locate them. Marking them with a unique identifier makes it possible to do that. Second, you want to be able to track the status of each item as it changes. Third, if a change is made to one of your configuration items, you want to be able to determine the impact of that change on the other items.

Configuration Control

Configuration control refers to the process of identifying, evaluating and approving changes (as laid out in the architecture maintenance plan) and then updating the baseline and all associated documentation. Any additions after the initial release/baseline will be noted with a changed version number and date to the relevant identifiers. This must also include an update and new version of the overall configuration item list that documents the current versions of all configuration items.

In the case of a regional ITS architecture the baseline consists of databases, documents, and possibly other supporting outputs such as spreadsheets or drawing files. The process of configuration control and of updating these can become challenging since there is likely to be more than a single representation of the same information. For example, if a database contains the architecture inventory and an architecture document contains a table that lists this inventory- these two representations of the same information need to be kept in sync. Eliminating this kind of duplication is not really an option because a database representation of the architecture is needed to manage to large number of elements and connections, but some form of documentation is also required to make the information more understandable and usable for the stakeholders. The solution is to be aware of the duplication and to put in place a plan to manage it. Because of the potential for changes affecting multiple parts of the baseline, the changes in each part of the baseline should be coordinated with updates in other parts of the baseline. This is particularly true when using the incremental change approach to architecture maintenance.

In the incremental change approach, it is also possible to

allow the database version of the information to change more frequently than

the documentation. This might be appropriate if the form of the information

used most often by stakeholders is the database (e.g. in the mapping of

regional ITS architecture to projects). This could be handled by notes in the

configuration item list.

In the incremental change approach, it is also possible to

allow the database version of the information to change more frequently than

the documentation. This might be appropriate if the form of the information

used most often by stakeholders is the database (e.g. in the mapping of

regional ITS architecture to projects). This could be handled by notes in the

configuration item list.

Configuration Status Accounting

Configuration status accounting is the process of ensuring that all of the relevant information about an item — documentation and change history — is up to date and as detailed as necessary. This includes the status of all pending changes. A primary goal of configuration status accounting is to disseminate configuration item information necessary to support existing and future change control efforts. A typical configuration status accounting system involves establishing and maintaining documentation for the entire life cycle of an item. Status accounting is ideally carried out in conjunction with change control.

The primary benefit of configuration status accounting is that it provides a methodology for updating all relevant documentation to ensure that the most current configuration is reflected in the configuration identification database. It accounts for the current status of all proposed and approved changes. The goal of configuration status accounting is to provide decision makers with the most up-to-date information possible. Having the most recent information about a change item or including how the changes were implemented helps to reduce research efforts in future change control activities whether implementing a new change or rolling back a change that had a negative or unexpected impact. To report status, a format similar to that shown in Figure 57 might be used:

Figure 57. Sample Configuration Identification Document

For a small regional ITS architecture, the only configuration items might be a document and a Turbo database. This would mean that configuration status accounting amounts to reporting on the version of the two configuration items (e.g. ruralRegArchV1-6-3-03.tbo and ruralRegionarchV1-7-3-03.doc are the latest versions of the "rural region ITS architecture"). Reporting this status could be done by phone call, letter, email or fax to interested stakeholders just to let them know that these files are still the latest. When using the incremental change approach, the other thing typically reported during status accounting would be the list of pending changes to the regional ITS architecture, and for a small region there may not be very many changes typically encountered and these may be very infrequent. So, in addition to identifying the latest version of the architecture, the region might report that there have been 2 changes received from stakeholder A and B that these haven't been implemented yet but are expected to be worked on in the next 6 months. When using a full baseline update approach pending changes are collected but probably not reported until summarized in the change log that occurs when the full baseline is updated.

Configuration Audits

In the general discipline of configuration management, configuration verification and audit is the process of analyzing configuration items and their respective documentation to ensure that the documentation reflects the current situation. In the case of a regional ITS architecture the configuration items are the documentation. Hence this step in the process becomes a rather simple one that can look at two aspects of the architecture:

This type of audit is most applicable when using the incremental change approach (which may result in many small updates to configuration items, but is also a good idea to perform at the end of the effort in the full baseline update.

How much effort must be expended to maintain a regional ITS architecture? That is dependent on several factors:

To identify the effort required consider several maintenance scenarios:

How many changes are collected in each period is very dependent on use of the architecture (how much is it being looked at while stakeholders are using it) as well as the complexity of the architecture (how many elements or connections could be changed). Creating a change request should be a small time investment for any submitter (e.g. under an hour of time). There is a small time investment of the maintaining organization to log the changes. Periodically, changes would be evaluated and presented to the maintenance committee. Evaluating each change will take only a small time investment. A maintenance committee meeting of a couple hours will dispose of the changes. The amount of effort required to update the baseline will be a function of the scope of the change (e.g. adding a new stakeholder, inventory items and connections will take longer than changing the status of a few information flows). Again, the amount of effort for the activities described above is dependent on the number of changes being considered.

This scenario is very similar to the previous one (in terms of time required for each change). The primary difference would be the number of changes to be incorporated. Again the amount of effort will be highly dependent on such things as the level of ITS investment in the region. One way to limit the amount of effort required in the evaluation and approval part of the process is to have maintainer staff produce a summary of changes and recommended outcomes (approve, defer, or reject). This will allow the maintenance committee to focus on only those changes requiring significant stakeholder consensus when it meets.

This is the full baseline update approach. In this approach, additional time will be spent getting some subset of the stakeholders together in one or more workshops to review the architecture. A series of changes will naturally flow from these meetings that can be incorporated en masse into the architecture. The level of effort required for these meetings will be dependent on how many meetings are planned and how much effort will be required to present the architecture to the stakeholders.

So how much will it cost? We all have to answer to the realities of budgeting and planning which forces us all to the bottom line. The cost of maintaining a regional ITS architecture depends on how you are going to use it. As you can see from the discussion above, the cost of paying someone to update the database, web site, and documents may be trivial compared to the cost of all of the stakeholders' time reviewing and approving changes. Think about the scenarios above and decide what maintenance approach your region will likely follow. Based on that decision you can then decide whether to allocate some financial resources to your future budgets to cover the cost of maintenance — personnel, equipment, contractors, etc. If the regional ITS architecture is going to be maintained by the MPO, then they should consider making architecture maintenance a work item in their Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP).

In 2005, FHWA developed the "Regional ITS Architecture

Maintenance Resources: Technical Advisory," that went into more

detail on the topic of the resources required to maintain an ITS architecture —

staffing, training, time, etc. Go to the FHWA Architecture Implementation

page, http://www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/its_arch_imp/index.htm,

click on "Resources" and find the link to the Technical Advisory.

In 2005, FHWA developed the "Regional ITS Architecture

Maintenance Resources: Technical Advisory," that went into more

detail on the topic of the resources required to maintain an ITS architecture —

staffing, training, time, etc. Go to the FHWA Architecture Implementation

page, http://www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/its_arch_imp/index.htm,

click on "Resources" and find the link to the Technical Advisory.