Regional ITS Architecture Guidance Document

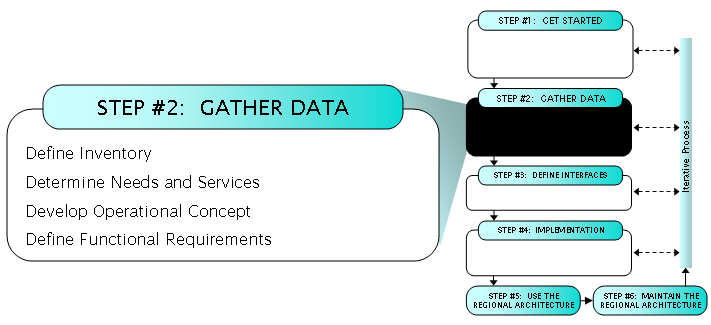

This section describes the second step in the regional ITS architecture development process — "Gather Data".

In this step, the data necessary to build a regional ITS architecture is assembled. An inventory of the ITS elements in the region is taken, the roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder in developing, operating, and maintaining the ITS elements is documented, the ITS services that should be provided in the region are identified, and the contribution (in terms of functionality) that each ITS element will make to provide these ITS services is documented.

In this section, the four "Gather Data" process tasks are described in more detail. Each task description begins with a one page summary that is followed by additional detail on the process, relevant resources and tools, a general description of the associated outputs, and example outputs where they are available. Each task description also includes tips and cautionary advice that reflect lessons that have been learned in development of regional ITS architectures over the past several years.

| These tasks may be performed in parallel. |

|

|---|---|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

| PROCESS Key Activities |

Prepare

|

|

INPUT Sources of Information |

|

|

OUTPUT Results from Process |

|

Each stakeholder agency, company, or group owns, operates, or maintains ITS systems in the region. In this step, a comprehensive inventory of "ITS elements" is developed that represent these systems, based on existing inventories and stakeholder input.

An inventory of existing and planned ITS elements supports development of interface requirements and information exchanges with these ITS elements as required in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)6 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.6.

An inventory of existing and planned ITS elements supports development of interface requirements and information exchanges with these ITS elements as required in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)6 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.6.

The process of creating an inventory of ITS elements starts with collecting existing inventory information. This can often provide an excellent jumpstart to the inventory definition. In addition to existing plans, studies, and project documentation, adjacent or overlapping regional ITS architectures are a good source for inventory information. A portion of the inventory in these architectures will often be relevant, saving time and improving consistency between adjacent or overlapping architectures. It is best to develop a partial inventory based on these resources prior to engaging a large number of stakeholders to make best use of stakeholder time.

It is helpful to establish a naming convention before assembling the inventory. For example, the names that are used in the inventory should start with a standard prefix since the inventory will frequently be viewed and managed as an alphabetized list of names. Prefixes can be a concise and consistent reference to the stakeholder (e.g., XYZ Transit), a reference to the location (City ABC), or any other standard prefix that will group similar ITS elements when the inventory is sorted by name. By establishing and using a naming convention at the outset, the inventory will be easier to read and manage, and there will be less rework later to rename and reorganize the inventory after it is assembled.

It is helpful to establish a naming convention before assembling the inventory. For example, the names that are used in the inventory should start with a standard prefix since the inventory will frequently be viewed and managed as an alphabetized list of names. Prefixes can be a concise and consistent reference to the stakeholder (e.g., XYZ Transit), a reference to the location (City ABC), or any other standard prefix that will group similar ITS elements when the inventory is sorted by name. By establishing and using a naming convention at the outset, the inventory will be easier to read and manage, and there will be less rework later to rename and reorganize the inventory after it is assembled.

When building an inventory, focus first on the "centers" since they are typically involved in the majority of inter-agency and public/private interfaces that need the most attention. Focus next on the field, vehicle, and traveler ITS elements where there is some opportunity for integration. Next consider other ITS elements that are in the region that may interface with ITS. Airports, asset management systems, and special event centers are examples of ITS elements in the region that may provide integration opportunities and should be included in the inventory. Finally, consider centers in adjacent regions, like the TMC in the adjacent state. The objective is to identify the ITS elements in the region that will allow integration opportunities to be identified and considered later in the process. Unless the region has unique needs, don't include ITS elements in the inventory for people (e.g., traffic operations personnel) or environmental terminators (e.g., roadway environment). The focus should be on the systems in the region that may be integrated. Systems with no potential for integration (e.g., an isolated traffic signal in a remote community) need not be included in the inventory.

Working closely with the stakeholders as the inventory is expanded and refined improves the quality of the inventory and increases stakeholder awareness of the existing and planned transportation systems in the region. Many different mechanisms may be used to gather stakeholder input including workshops, smaller meetings, telephone surveys, e-mail, and web-based interactions. Plan to use one or more of these mechanisms to verify and improve the inventory with stakeholder feedback. It may be helpful to engage a few key stakeholders initially and then encourage a broader review once the inventory is substantially complete.

The inventory should cover the geographic, timeframe and services scope specified for the region. The inventory, representing many existing and planned systems that may be implemented over ten or twenty years, can be developed in a single pass or in multiple passes. For example, you might start with an inventory of existing ITS elements, then add planned elements (i.e., elements that have been programmed), and finally add future elements that may be implemented towards the end of the established timeframe.

Security Considerations

The regional ITS inventory that is compiled should be reviewed to identify critical assets — systems that, if lost, would jeopardize the ability of the regional transportation system to provide a primary function or threaten public safety. Any existing regional analysis of critical assets can be used as a starting point, if available. In later steps, the regional ITS architecture will be organized to protect these critical assets and security services. Security mechanisms will be defined to isolate these critical assets from non-critical assets. The security analysis associated with each National ITS Architecture subsystem can provide an input to the identification of the security-critical elements in the ITS inventory.

The regional ITS inventory that is compiled should be reviewed to identify critical assets — systems that, if lost, would jeopardize the ability of the regional transportation system to provide a primary function or threaten public safety. Any existing regional analysis of critical assets can be used as a starting point, if available. In later steps, the regional ITS architecture will be organized to protect these critical assets and security services. Security mechanisms will be defined to isolate these critical assets from non-critical assets. The security analysis associated with each National ITS Architecture subsystem can provide an input to the identification of the security-critical elements in the ITS inventory.

In addition to existing plans, studies, and project documentation that may be available in the region, the ITS Deployment Tracking Database (http://www.itsdeployment.its.dot.gov) may also be used as a source of existing ITS inventory information. This database contains information on ITS deployments in metropolitan areas based on surveys of metropolitan areas and states.

In addition to existing plans, studies, and project documentation that may be available in the region, the ITS Deployment Tracking Database (http://www.itsdeployment.its.dot.gov) may also be used as a source of existing ITS inventory information. This database contains information on ITS deployments in metropolitan areas based on surveys of metropolitan areas and states.

The  National ITS Architecture subsystems and terminators can be used to organize the ITS elements in the inventory. For example, Traffic Operations Centers and Public Safety Communications Centers may be associated with the Traffic Management Subsystem and Emergency Management Subsystem respectively. This association, or "mapping" to the National ITS Architecture establishes an important connection between the regional ITS architecture and the National ITS Architecture. The subsystems and terminators can also serve as a checklist that may be used to identify gaps in the inventory. The subsystems and terminators are defined in the Physical Architecture on the architecture CD-ROM and web sites.

National ITS Architecture subsystems and terminators can be used to organize the ITS elements in the inventory. For example, Traffic Operations Centers and Public Safety Communications Centers may be associated with the Traffic Management Subsystem and Emergency Management Subsystem respectively. This association, or "mapping" to the National ITS Architecture establishes an important connection between the regional ITS architecture and the National ITS Architecture. The subsystems and terminators can also serve as a checklist that may be used to identify gaps in the inventory. The subsystems and terminators are defined in the Physical Architecture on the architecture CD-ROM and web sites.

Turbo Architecture was specifically designed to support development of ITS inventories. Turbo provides interview questions and forms that can be used to rapidly develop an ITS Inventory for a region.

Turbo Architecture was specifically designed to support development of ITS inventories. Turbo provides interview questions and forms that can be used to rapidly develop an ITS Inventory for a region.

A regional ITS architecture inventory is a list of all existing and planned ITS elements in a region as well as non-ITS elements that provide information to or get information from the ITS elements. The focus should be on those elements that support, or may support, interfaces that cross stakeholder boundaries (e.g., inter-agency interfaces, public/private interfaces).

There is wide latitude in the types of ITS elements that may be included and the level of granularity that should be specified in an inventory. Although every inventory will vary based on the unique needs of the region, several general "best practices" guidelines can be offered to those preparing an inventory.

In general, the inventory should be managed so that it is as small as possible while still supporting the goal of identifying all key integration opportunities in the region. For example, instead of identifying separate inventory elements for each type of field equipment (e.g., separate elements for VMS, signal, camera, etc.), consider identifying a single inventory element that includes all of the field equipment as depicted in Figure 5.

In general, the inventory should be managed so that it is as small as possible while still supporting the goal of identifying all key integration opportunities in the region. For example, instead of identifying separate inventory elements for each type of field equipment (e.g., separate elements for VMS, signal, camera, etc.), consider identifying a single inventory element that includes all of the field equipment as depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Grouping ITS Elements into General Inventory Elements

Of course, ITS elements cannot be grouped into general elements indiscriminately. Multiple ITS elements can be safely grouped into a single inventory element if they exchange the same types of information with the same elements, and if they will be deployed for the same function over time. (E.g. message signs for a freeway and message signs for transit traveler information at a bus stop probably should be identified as separate ITS elements because of the very different requirements for these ITS elements.) The grouping works in Figure 5 because all the Heartland field equipment interfaces exclusively with the Heartland TOC, and for example, might be part of a single freeway management system deployment project. If some of the field equipment was actually owned and operated by another agency, then it might be best to identify a separate ITS element for that equipment group.

Another consideration is that when ITS elements are grouped in the inventory, the potential interfaces between these elements are lost (e.g., any potential interface between different types of Heartland field equipment is lost with the grouping in Figure 5). Again, the grouping in Figure 5 is acceptable because the interface between field equipment is (presumably) not a significant regional interface. The last issue is the affect that that grouping has on ITS standards identification later in the process. Due to the grouping, the combination of ITS standards that support Dynamic Message Signs, CCTV Control, and Signal Control will all be associated with the interface to the combined Field Equipment Element. This means that the ITS standards information for the element must be interpreted and used carefully to ensure that device-specific standards are identified and used properly later in the process. As long as the ITS element grouping is done with these issues in mind, recent experience indicates that grouping will save regional ITS architecture development time with little or no impact to the quality and utility of the final architecture.

The level of granularity in the inventory can vary

within a single regional ITS architecture. For example, larger systems in a

major metropolitan area may be explicitly identified (e.g., "District 8 Freeway

Management Center"), but smaller systems may be represented more broadly with a

few general ITS elements (e.g., "Municipal Police Dispatch Centers"). The

approach of "rolling up" smaller systems into a general inventory element

suggests that these systems should integrate with other regional elements in a

consistent fashion. A detailed list of the agencies and systems represented by

the general ITS element can be included in the definition for the element.

The level of granularity in the inventory can vary

within a single regional ITS architecture. For example, larger systems in a

major metropolitan area may be explicitly identified (e.g., "District 8 Freeway

Management Center"), but smaller systems may be represented more broadly with a

few general ITS elements (e.g., "Municipal Police Dispatch Centers"). The

approach of "rolling up" smaller systems into a general inventory element

suggests that these systems should integrate with other regional elements in a

consistent fashion. A detailed list of the agencies and systems represented by

the general ITS element can be included in the definition for the element.

An inventory may include a few ITS elements that are outside the defined scope of the region. For example, a Statewide ITS Architecture inventory may include ITS element(s) representing operations centers in adjacent states where there are important interfaces to these operations centers. These "inter-regional" interfaces should be coordinated across regional ITS architectures to avoid duplicate and/or conflicting definitions of the same interface .The names of the ITS elements in both regional ITS architectures must be identical when they represent the same system, and the interfaces defined in both regional ITS architectures should be identical when they describe the same information exchange across regional ITS architecture boundaries.

Each element in an inventory will normally include a name, associated stakeholder(s), a concise description, general status, and the associated subsystems or terminators from the National ITS Architecture. This core information may be supplemented with specific location information, points of contact, other references, and various implementation details as needs dictate. The region should establish the information that is required for each inventory element based on the needs of the region and available resources.

The fields that are normally included for each inventory element are described in the following paragraphs.

Element Name: Each element name should be selected with several criteria in mind. Most importantly, the selected name should be easily recognizable by the stakeholders. Preferably, the name will be the "common usage" name for the element in question, or at least be in terms that are familiar to the stakeholders.

While they may not seem important at the outset, naming conventions are a big help, particularly for large inventories. As discussed earlier, standard prefixes (e.g., "City ABC" or "County") ensure that related elements are sorted together when the inventory is alphabetized. The name of the element immediately follows the prefix to complete the element name. It is best to use the same names when referring to the same types of elements or equipment. For example, avoid using "roadside assets", "field equipment", and "roadway systems" for three different inventory elements covering similar field equipment for three different traffic agencies. Pick a name (e.g., "Field Equipment") that the stakeholders like, and then use it consistently where possible (e.g., "City ABC Field Equipment", "City XYZ Field Equipment", "XDOT Field Equipment"). Consistent names make the architecture easier to understand, maintain, and use.

While they may not seem important at the outset, naming conventions are a big help, particularly for large inventories. As discussed earlier, standard prefixes (e.g., "City ABC" or "County") ensure that related elements are sorted together when the inventory is alphabetized. The name of the element immediately follows the prefix to complete the element name. It is best to use the same names when referring to the same types of elements or equipment. For example, avoid using "roadside assets", "field equipment", and "roadway systems" for three different inventory elements covering similar field equipment for three different traffic agencies. Pick a name (e.g., "Field Equipment") that the stakeholders like, and then use it consistently where possible (e.g., "City ABC Field Equipment", "City XYZ Field Equipment", "XDOT Field Equipment"). Consistent names make the architecture easier to understand, maintain, and use.

Including a stakeholder prefix and system name in each ITS element name can make the names fairly long. Abbreviations and acronyms are a big help in keeping the names short enough so that they fit in the various diagrams and tables that will be used to publish the inventory. Care should be taken, though, to ensure that all of the abbreviations and acronyms make sense to the stakeholders.

Associated Stakeholders: While stakeholders can participate in the consensus of any part of the regional ITS architecture, they often are most interested in the inventory elements that they own, operate, or maintain. Documenting the association between stakeholders and ITS elements is useful since it allows stakeholders to rapidly identify their own elements. This association helps individual stakeholders make the most effective use of their time. If individual stakeholders don't have time to review the entire regional ITS architecture, they might still be able to review all sections that involve their associated agency, company or interest group, as identified by the associated stakeholder.

Description:  While it may be tempting to include very detailed information in the element description when it is available (e.g., the numbers and types of controllers included in a particular ITS element), remember that this level of detail will increase the level of effort required to maintain the regional ITS architecture later. In general, the architecture inventory should not specify technologies or manufacturers since this information is subject to change and incidental to the purpose of the regional ITS architecture. Limit the information to what is required for the stakeholders to recognize the element and its role (i.e., "what does it do?") in the regional ITS architecture. Where a general element is used to represent many systems, the description could include an explicit list of these systems. Additional detailed information that is compiled can be archived separately for later use.

While it may be tempting to include very detailed information in the element description when it is available (e.g., the numbers and types of controllers included in a particular ITS element), remember that this level of detail will increase the level of effort required to maintain the regional ITS architecture later. In general, the architecture inventory should not specify technologies or manufacturers since this information is subject to change and incidental to the purpose of the regional ITS architecture. Limit the information to what is required for the stakeholders to recognize the element and its role (i.e., "what does it do?") in the regional ITS architecture. Where a general element is used to represent many systems, the description could include an explicit list of these systems. Additional detailed information that is compiled can be archived separately for later use.

Associated Subsystems/Terminators: Each regional ITS architecture inventory element should be mapped to one or more National ITS Architecture subsystems and/or terminators. This association must be created because it will lead to identification of functional requirements for the ITS element, and architecture flows and supporting ITS standards in later steps. Occasionally, an element will be truly unique and not represented in the National ITS Architecture at all. In this case, no National ITS Architecture association is created. This is a perfectly valid approach, but it does mean that the functionality, architecture flows, and standards that are identified later for the element will not have a basis in the National ITS Architecture.

Although inventories all tend to include approximately the same information, many different ways to document this information have been devised. Excerpts from three different inventory presentations are included in this section to illustrate some of the ways that inventories have been documented.

Example 1: Inventory Summary Sorted by Stakeholder Name

An inventory summary can be presented in tabular form as shown in an excerpt from the Florida District 3 regional ITS architecture in Figure 6. The table is sorted by stakeholder name so that stakeholders can easily find the elements that are associated with their agency, company or user group. For example, a City of Pensacola employee could rapidly see that there are four elements in the regional ITS architecture that are associated with his or her agency: City of Pensacola Field Equipment; City of Pensacola Traffic Operations Center; FDOT District 3 Escambia/Santa Rosa County RTMC, and Pensacola Regional Airport. (Note that "FDOT D3/Pensacola/Escambia Cty/Santa Rosa Cty" is a named stakeholder group that includes the City of Pensacola as well as Escambia County, FDOT District 3, and Santa Rosa County.)

Figure 6: Florida DOT District 3 Inventory by Stakeholder Excerpt

Example 2: Detailed Inventory Information Presentation

Figure 7 shows more comprehensive inventory information for a particular ITS element: "FDOT District 3 Escambia/Santa Rosa County RTMC" (note that RTMC means "Regional Traffic Management Center"), in the FDOT District 3 regional ITS architecture. This figure shows the element status, a brief description of the element, who the owning/operating stakeholder is, and a listing of the National ITS Architecture entities (subsystems and terminators) to which the element is mapped.

Figure 7: Inventory Details for a Florida DOT District 3 ITS Element

Example 3: Subsystem Diagram Inventory Presentation

The association or mapping between regional ITS architecture elements and the National ITS Architecture is also frequently depicted in an extended version of the "Subsystem Diagram" as illustrated in Figure 8. This diagram is also taken from the FDOT District 3 regional ITS architecture. Here, the generic subsystem diagram is expanded so that each subsystem (and terminator, even though they are not normally shown in a subsystem diagram) is associated with specific inventory elements in Florida DOT District 3.

Figure 8: Florida DOT District 3, Extended Subsystem Diagram

| These tasks may be performed in parallel. |

|

|---|---|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

| PROCESS Key Activities |

Prepare

|

|

INPUT Sources of Information |

|

|

OUTPUT Results from Process |

|

In the previous step, an inventory of the existing and planned ITS elements in the region was developed. In this step, the ITS services that should be provided by these elements to address regional needs are identified. This is the first step in determining what the ITS elements should do tomorrow that they do not do today. It provides each agency an opportunity to look at the region's transportation system from the highest level and confirm that their goals and desires are consistent with the rest of the transportation community.

An understanding of the regional needs and ITS services supports development of interface requirements and information exchanges with planned and existing ITS elements as required in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)6 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.6.

An understanding of the regional needs and ITS services supports development of interface requirements and information exchanges with planned and existing ITS elements as required in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)6 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.6.

Identify Needs

Before ITS services can be prioritized for the region, the problems with the regional transportation system and the associated needs of the operators, maintainers, and users of the system must be understood. In many cases, regional needs will already be documented in one or more existing plans or studies. Even when they are not formally documented in one place, the operators, maintainers, and users of the system generally understand the region's needs. Needs are identified by collecting this information from existing documents and supplementing this information with stakeholder input.

Both ITS plans and traditional transportation plans should be reviewed for needs and services information. Transportation long range plans typically discuss economic and social trends and how the infrastructure should be built to meet the region's needs. Many of these long term policies and goals are directly related to the needs and services that guide a regional ITS architecture. For example, if major new facilities are planned for the region, then it is appropriate to plan to add ITS services into those new facilities. If the region is making major investments in enhancing transit service, these enhanced services should be reflected in the regional ITS architecture.

The needs collected from this documentation review can then be reviewed and refined with key stakeholders in the region. It is best to start with a candidate list of needs when gathering stakeholder input. If a set of needs for the region has not been documented, a representative list of candidate needs can be used to start the discussion. Based on stakeholder input, the region's needs are documented before (or sometimes at the same time that) ITS services are considered. Ideally, needs are developed prior to developing ITS services, but in some practical scenarios, an iterative process is followed. As needs are better understood by stakeholders through discussion of ITS services, stakeholders can then more precisely document their needs.

It is common to find transportation solutions embedded in lists of regional transportation needs. When identifying needs, it is important to help stakeholders to define their needs in terms of problems that need to be solved (e.g., "Improve security around key transportation infrastructure") rather than as specific solutions (e.g., "Install CCTV cameras and a 24/7 monitoring center"). The solutions are developed through the architecture development and project systems engineering analysis steps that follow. It is important not to jump to a solution prematurely at this early step in the analysis.

It is common to find transportation solutions embedded in lists of regional transportation needs. When identifying needs, it is important to help stakeholders to define their needs in terms of problems that need to be solved (e.g., "Improve security around key transportation infrastructure") rather than as specific solutions (e.g., "Install CCTV cameras and a 24/7 monitoring center"). The solutions are developed through the architecture development and project systems engineering analysis steps that follow. It is important not to jump to a solution prematurely at this early step in the analysis.

Determine Services — User Services and Market Packages

ITS services are the things that can be done to improve the efficiency, safety, and convenience of the regional transportation system through better information, advanced systems and new technologies. ITS services are prioritized for the region based on the documented regional needs.

The first task is to determine the initial list of ITS services that will be reviewed and prioritized for the region. ITS services can be described in a variety of ways — the most common lists of ITS services are the "User Services" and "market packages".

Thirty-three User Services covering a wide breadth of surface transportation needs have been defined. User services are generally a technology neutral and architecture neutral statement of services. User services identify what a regional intelligent transportation system must do, but do not say how functions will be allocated to ITS elements or how ITS elements will communicate with each other to address those needs. This is in direct contrast to Market Packages.

Market packages have been used as the initial list of ITS services by many regional ITS architectures. Market packages provide a service-oriented view of the National ITS Architecture that identify the pieces of the architecture that are required to implement a particular service. There are a few compelling reasons to use market packages to identify services:

While market packages are a good place to start, it would be a mistake to limit the ITS service choices to the list of predefined market packages since some services that are important to the region may not be defined in the National ITS Architecture market packages. For example, in the Greater Yellowstone regional ITS architecture development, new market packages were developed for six additional rural ITS services that were important to the Yellowstone region but not represented in the National ITS Architecture at the time that this regional ITS architecture was developed (e.g., Animal-Vehicle Collision Counter Measures). Other regions have added services like red light enforcement, flood monitoring, and over-dimension vehicle permitting coordination to the services identified by the National ITS Architecture.

While market packages are a good place to start, it would be a mistake to limit the ITS service choices to the list of predefined market packages since some services that are important to the region may not be defined in the National ITS Architecture market packages. For example, in the Greater Yellowstone regional ITS architecture development, new market packages were developed for six additional rural ITS services that were important to the Yellowstone region but not represented in the National ITS Architecture at the time that this regional ITS architecture was developed (e.g., Animal-Vehicle Collision Counter Measures). Other regions have added services like red light enforcement, flood monitoring, and over-dimension vehicle permitting coordination to the services identified by the National ITS Architecture.

Beginning with a list of market packages or an alternative list of ITS services, services should be identified that:

Stakeholder input on each of these choices should be actively solicited, preferably in a direct forum like a brainstorming session or workshop. Remember that the focus for this task is on identifying the important ITS services; avoid getting bogged down in the specifics of how those services will be provided in this process step.

To make best use of stakeholder representative time, focus group discussion on ITS services that require group buy-in. ITS services that can be implemented by a single agency require less discussion than ITS services that require integration between different stakeholders' ITS elements. For example, the decision to deploy a Surface Street Control service is an individual decision for a particular traffic agency, and may not be a priority for group discussion. In contrast, the decision to deploy Transit Signal Priority requires consensus by traffic and transit agencies and should be agreed to by all parties. Individual agency service choices can be coordinated offline if time is short.

To make best use of stakeholder representative time, focus group discussion on ITS services that require group buy-in. ITS services that can be implemented by a single agency require less discussion than ITS services that require integration between different stakeholders' ITS elements. For example, the decision to deploy a Surface Street Control service is an individual decision for a particular traffic agency, and may not be a priority for group discussion. In contrast, the decision to deploy Transit Signal Priority requires consensus by traffic and transit agencies and should be agreed to by all parties. Individual agency service choices can be coordinated offline if time is short.

It is usually appropriate to focus the discussion on services that have public sector involvement. Market packages that are exclusively private sector with no public sector interfaces (e.g., some autonomous vehicle safety and guidance market packages) can generally be excluded.

Every ITS service selected for the region should be associated with one or more inventory elements that supports or will support that service. Each of these associations should be reviewed and approved by stakeholders associated with the regional ITS elements. This association between ITS services and ITS stakeholders will be the starting point for operational concepts, which will be defined in the next process task.

Many different resources discuss "needs" in the context of ITS and surface transportation planning. One such source is "Integrating Intelligent Transportation Systems within the Transportation Planning Process" (EDL #3903, http://ntl.bts.gov/lib/jpodocs/repts_te/3903.pdf)

Many different resources discuss "needs" in the context of ITS and surface transportation planning. One such source is "Integrating Intelligent Transportation Systems within the Transportation Planning Process" (EDL #3903, http://ntl.bts.gov/lib/jpodocs/repts_te/3903.pdf)

This document discusses the relationship between transportation goals, problems, and needs. Other resources provide detailed information on the benefits of ITS that can be used to determine the ITS services that will address regional needs. The Program Assessment Section of the ITS Joint Program Office Website is a good place to start your search for benefits information (http://www.benefitcost.its.dot.gov/).

Both market packages and user services provide a service-oriented view of ITS that can be used to support ITS service selection and definition. Both are included in the National ITS Architecture documentation. The "User Services Document" can be found on the National ITS Architecture website at http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/html/menu/documents.htm. Market Packages are also documented on the National ITS Architecture website (http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/html/mp/mpindex.htm), that provides wealth of information that can support market package selection including tables that relate market packages to transportation problems and solutions, ITS Goals, and user services. Each market package includes a market package graphic, one or more transaction set diagrams, a description, and a detailed listing of the subsystems, terminators, equipment packages, and architecture flows that are included.

Both market packages and user services provide a service-oriented view of ITS that can be used to support ITS service selection and definition. Both are included in the National ITS Architecture documentation. The "User Services Document" can be found on the National ITS Architecture website at http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/html/menu/documents.htm. Market Packages are also documented on the National ITS Architecture website (http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/html/mp/mpindex.htm), that provides wealth of information that can support market package selection including tables that relate market packages to transportation problems and solutions, ITS Goals, and user services. Each market package includes a market package graphic, one or more transaction set diagrams, a description, and a detailed listing of the subsystems, terminators, equipment packages, and architecture flows that are included.

Turbo Architecture directly supports market package selection and association of ITS elements that support the market package.

Turbo Architecture directly supports market package selection and association of ITS elements that support the market package.

Multiple "market package instances" may be created when the same market package is implemented multiple times in the same region. Turbo uses these market package choices to generate an initial architecture based on the underlying National ITS Architecture definition for each market package. Turbo can also generate or export market package choice information consistent with the output guidelines provided below.

The output of this process step is a list of regional needs and the ITS services that will be implemented in the region.

Needs

Needs should be documented completely, including a record of the agencies and/or areas(s) in the region that have the need. For example, specify "alleviate congestion in work zones, freeway interchanges, and CBD" rather than simply identifying "alleviate traffic congestion" as a regional need. This detail will be helpful when assigning ITS services to inventory elements.

Even more detail could be added at the discretion of the region (e.g., "alleviate recurring congestion on SB I-5 to SB SR-55 interchange during morning peak"), but remember that this additional detail will be subject to change and increase maintenance on the regional ITS architecture. This level of detail is not necessary for the regional ITS architecture where needs and services only have to be isolated to the agency or ITS element level. This level of detail would be necessary to support more detailed project definitions.

Even more detail could be added at the discretion of the region (e.g., "alleviate recurring congestion on SB I-5 to SB SR-55 interchange during morning peak"), but remember that this additional detail will be subject to change and increase maintenance on the regional ITS architecture. This level of detail is not necessary for the regional ITS architecture where needs and services only have to be isolated to the agency or ITS element level. This level of detail would be necessary to support more detailed project definitions.

ITS Services

This documentation identifies each ITS service that is, or will be implemented in the region. For example, if market packages are used, the output would identify each market package name, its status in the region (e.g., existing, planned, or not planned), a list of the regional elements that will implement the market package, and any special notes concerning tailoring or issues associated with the market package. Some regions have added a priority rating to the market package that reflects the stakeholders' prioritization of the various service options.

An example of a list of needs (from the Colorado DOT Region 4 ITS Plan, February 16, 2004) in a region is shown in Figure 9. In general, the identified needs are scoped at a high and appropriate level, e.g., "improved management of road closures" or "ice detection and control". This statement of needs is architecture neutral.

Figure 9: Example list of Regional Needs

A few of the listed needs in this example (e.g., "Greater density of weather stations and pavement sensors") specify a solution. One good technique for determining the underlying need when a stakeholder identifies a specific solution as a need is to ask the stakeholder "why" several times to better understand the underlying need. In this case, do the users want more weather stations to detect storm cells that cause localized flooding, predict icing and warn drivers, monitor snowfall and proactively manage snow removal, or to satisfy some other need? If you can identify and document the underlying transportation need, then all viable solutions can be considered in subsequent steps.

A few of the listed needs in this example (e.g., "Greater density of weather stations and pavement sensors") specify a solution. One good technique for determining the underlying need when a stakeholder identifies a specific solution as a need is to ask the stakeholder "why" several times to better understand the underlying need. In this case, do the users want more weather stations to detect storm cells that cause localized flooding, predict icing and warn drivers, monitor snowfall and proactively manage snow removal, or to satisfy some other need? If you can identify and document the underlying transportation need, then all viable solutions can be considered in subsequent steps.

The same regional ITS architecture that had the list of needs shown in Figure 9, also selected market packages against the user needs; some of the selected market packages (for the ATMS related needs) are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: ATMS Market Packages Identified to Support Needs

Other regional ITS architectures include tables that document the ITS services using market package instances that were selected and customized for the region. In the Florida DOT District 3 Regional ITS Architecture, each ITS element in the region has a report that shows in which market package instances they participate. The report for the City of Gulf Breeze Field Equipment is shown in Figure 11. This report shows that this ITS element participates in six market package instances, including two instances of market package ATMS01 — Network Surveillance.

Figure 11: ITS Element Report with Market Package Instances

| These tasks may be performed in parallel. |

|

|---|---|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

| PROCESS Key Activities |

Prepare

|

|

INPUT Sources of Information |

|

|

OUTPUT Results from Process |

|

The inventory identifies the stakeholders that are associated with each ITS element in the region. In this step, each stakeholder's current and future roles and responsibilities in the operation of the regional services are defined in more detail. The operational concept documents these roles and responsibilities for selected transportation service areas relevant to the needs of the region, and optionally for specific operational scenarios. It provides an "executive summary" view of the way the region's stakeholders will work together to provide ITS services.

An operational concept that identifies the roles and responsibilities of participating agencies/stakeholders is one of the required components of a regional ITS architecture as identified in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)3 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.3.

An operational concept that identifies the roles and responsibilities of participating agencies/stakeholders is one of the required components of a regional ITS architecture as identified in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)3 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.3.

This is the process step where integration opportunities in the region are first documented, with particular focus on stakeholder involvement. The objective is not to formally define each ITS element or specify detailed integration requirements. This will come in later steps. The objective in this step is to identify current and future organizational roles in the regional transportation system. As with the other regional ITS architecture products, exactly how the operational concept information is gathered and expressed will vary from region to region.

The level of detail that is included in the operational concept will also vary from region to region. Some operational concepts will focus on a definition of each stakeholder's general role in providing the transportation services in the region. More detailed operational concepts may include a more detailed discussion of how stakeholders will interact to provide specific transportation services, possibly in specific scenarios. Stakeholder review and iteration is an important part of the process as initial concepts are expanded and refined.

Perhaps the most critical factor in the success of the Operational Concept process step is stakeholder involvement. The ultimate objective is not to create a table of roles and responsibilities, but to have the stakeholders suggest, review and tangibly buy in to these decisions so that they are owners of the operational concept. In later steps, these roles and responsibilities will form a basis for inter-agency agreements.

One of the significant challenges in developing an operational concept for a regional ITS architecture is the sheer scale and diversity of the systems and organizations that are included. It would be almost impossible to write a single contiguous operational concept that covers "a day in the life" of the regional surface transportation system.

One way to meet this challenge is to define several operational concept role and responsibility areas, each area covering a particular aspect of the transportation system. For example, a series of focused operational concepts could be developed that each address a particular ITS service.

In most cases, you will want to use the same structure in your operational concept that you used to determine services and needs for the region. For example, if market packages were used to prioritize services and needs, then operational concepts should be developed for the market packages that were identified as important to the region. A concise operational concept could be developed for each selected market package with emphasis on those market packages that require broad coordination across organizations. For example, "Incident Management" and "Regional Traffic Control" both require broad inter-agency coordination and may require more focus in the operational concept than a market package like "Network Surveillance", since the latter has comparatively few inter-agency interfaces and a narrower focus.

In most cases, you will want to use the same structure in your operational concept that you used to determine services and needs for the region. For example, if market packages were used to prioritize services and needs, then operational concepts should be developed for the market packages that were identified as important to the region. A concise operational concept could be developed for each selected market package with emphasis on those market packages that require broad coordination across organizations. For example, "Incident Management" and "Regional Traffic Control" both require broad inter-agency coordination and may require more focus in the operational concept than a market package like "Network Surveillance", since the latter has comparatively few inter-agency interfaces and a narrower focus.

A common source of frustration when discussing roles and responsibilities with stakeholders at this early stage is that the discussions can be too conceptual to really engage many people. To better engage stakeholders in the process, consider using real operational situations, or scenarios, to guide the discussion. For example, a large winter storm or hazardous material spill can provide vivid context to a discussion of the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in the region. Create a scenario or scenarios that the stakeholders in the region are vitally interested in and then use the scenarios to encourage discussion and make the operational concept documentation more accessible.

A common source of frustration when discussing roles and responsibilities with stakeholders at this early stage is that the discussions can be too conceptual to really engage many people. To better engage stakeholders in the process, consider using real operational situations, or scenarios, to guide the discussion. For example, a large winter storm or hazardous material spill can provide vivid context to a discussion of the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in the region. Create a scenario or scenarios that the stakeholders in the region are vitally interested in and then use the scenarios to encourage discussion and make the operational concept documentation more accessible.

One way to use a scenario-based approach is to organize a meeting where a facilitator walks key stakeholders through the events of a prepared scenario. At each step in the scenario, the facilitator works with the group to determine:

The facilitator should be prepared for more "opportunities" to be identified than can be thoroughly addressed in real-time. A common approach is to list all the ideas and then prioritize a few to flesh out with an operational concept. To finish the above example, the facilitator might follow up and determine who would implement and operate the proposed road closure information system, who would be its customers, and who would provide closure information to it.

A forum like this is a good opportunity to verify that the stakeholders are supportive and prepared for the changes that will occur if the operational concepts are implemented. A range of issues, mostly non-technical, will often arise during the development of an operational concept, and they should be documented and resolved if possible. Among many effective strategies for issue resolution, it is often worthwhile to select a facilitator who has no vested interest in the issue to help steer those involved towards a win-win solution.

Security Considerations

From a security perspective, there are roles and responsibilities associated with making sure the security objectives are met. These roles and responsibilities can also be established as part of the operational concept, leveraging on organizations in the region that have specific interest and expertise in information security.

From a security perspective, there are roles and responsibilities associated with making sure the security objectives are met. These roles and responsibilities can also be established as part of the operational concept, leveraging on organizations in the region that have specific interest and expertise in information security.

User Services are service-oriented descriptions of ITS which include some information that may be relevant to regional ITS architecture operational concepts. For example, the user service documentation includes a high-level operational concept for each user service. As discussed earlier, the National ITS Architecture User Services are documented in the "User Services Document" which can be found on the National ITS Architecture website (http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/html/menu/documents.htm).

User Services are service-oriented descriptions of ITS which include some information that may be relevant to regional ITS architecture operational concepts. For example, the user service documentation includes a high-level operational concept for each user service. As discussed earlier, the National ITS Architecture User Services are documented in the "User Services Document" which can be found on the National ITS Architecture website (http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/html/menu/documents.htm).

The National ITS Architecture includes Market Packages, which can also be used as a basis for operational concept development. Basic market package information is accessible in hypertext format on the National ITS Architecture website. The National ITS Architecture documentation set also includes a "Theory of Operations" associated with each Market Package that describes in detail how transportation services are provided by the National ITS Architecture. This document is also a good resource for those developing operational concepts for a region, since the issuing of messages in response to receiving specific information inputs in the Theory of Operations can be the initial basis for stakeholder roles and responsibilities.

The National ITS Architecture includes Market Packages, which can also be used as a basis for operational concept development. Basic market package information is accessible in hypertext format on the National ITS Architecture website. The National ITS Architecture documentation set also includes a "Theory of Operations" associated with each Market Package that describes in detail how transportation services are provided by the National ITS Architecture. This document is also a good resource for those developing operational concepts for a region, since the issuing of messages in response to receiving specific information inputs in the Theory of Operations can be the initial basis for stakeholder roles and responsibilities.

Finally, as discussed earlier, Turbo Architecture has an "Ops Concept" tab to aid the user in developing an operational concept based on the selected market packages and assignment of ITS elements to those market packages. Turbo will help the analyst to identify role and responsibility areas, select stakeholders that have roles and responsibilities in each area, and write roles and responsibilities for each selected stakeholder.

Finally, as discussed earlier, Turbo Architecture has an "Ops Concept" tab to aid the user in developing an operational concept based on the selected market packages and assignment of ITS elements to those market packages. Turbo will help the analyst to identify role and responsibility areas, select stakeholders that have roles and responsibilities in each area, and write roles and responsibilities for each selected stakeholder.

The operational concept for a regional ITS architecture identifies operational roles and responsibilities.

It is usually best to keep the operational concept at a fairly high level, assigning general roles and responsibilities to organizations rather than specific departments or individuals. If the operational concept is too detailed, it can actually hinder efforts since the more detailed data will be less certain and subject to change at this early stage. The more detailed concepts should be deferred until the implementation phase of a specific project.

It is usually best to keep the operational concept at a fairly high level, assigning general roles and responsibilities to organizations rather than specific departments or individuals. If the operational concept is too detailed, it can actually hinder efforts since the more detailed data will be less certain and subject to change at this early stage. The more detailed concepts should be deferred until the implementation phase of a specific project.

Operational Roles and Responsibilities

One effective way to organize the operational roles and responsibilities is by ITS service — using either user services or market packages to structure the output. For each ITS service, the operational concept provides a general view of how the service will be performed in the region and each stakeholder's roles and responsibilities in providing that service. In addition, the major areas of coordination between stakeholders can be documented. This is helpful because it will support the interface definitions and institutional agreements that are identified in later steps.

When documenting the roles and responsibilities for each ITS service, it's important to realize that an ITS service can often be implemented in several different ways. For example, emergency vehicle signal preemption can be implemented in at least two ways:

While the first alternative has been around longer, the second alternative could be attractive to regions that already have AVL implemented in their emergency vehicles and have a closed-loop signal control system in place. The operational concept should explore alternative concepts like this example and document choices for the region. For example, an operational concept for emergency vehicle signal preemption might select the first alternative, and then identify the roles and responsibilities of the public safety and traffic management agencies that would participate in the service. Where a firm choice cannot be made, several alternative concepts can be retained for future analysis.

Implementation Roles and Responsibilities

This portion of the operational concept includes a clear identification of the implementation and maintenance responsibilities for each of the stakeholders in the region.

More detailed information can be provided where the ITS elements are shared and the lines of responsibility are more complicated. For example, roles and responsibilities could be documented in a responsibility matrix showing shared resources on one axis and stakeholders on the other. Each cell would identify the stakeholder's responsibility for the shared resource.

More detailed information can be provided where the ITS elements are shared and the lines of responsibility are more complicated. For example, roles and responsibilities could be documented in a responsibility matrix showing shared resources on one axis and stakeholders on the other. Each cell would identify the stakeholder's responsibility for the shared resource.

Operational concepts can be documented in many different formats including textual descriptions, tables, and graphics. Each region is encouraged to review these examples and identify an approach that best meets their needs.

Example 1: Roles and Responsibilities using a simple table

The roles and responsibilities for stakeholders in the Vermont Statewide ITS Architecture are documented in a table, of which Table 4 is a partial view for one service, Incident Management. This operational concept documents the roles and responsibilities for transportation service areas, associated with high level user services. For each high level transportation service area, each relevant stakeholder is identified, and their specific operational roles and responsibilities are documented.

Example 2: Roles and Responsibilities using Turbo Architecture

Example 2: Roles and Responsibilities using Turbo Architecture

The roles and responsibilities for the North Dakota Regional ITS Architecture were developed using Turbo Architecture. Figure 12 shows the Ops Concepts tab for this regional ITS architecture, with all the role and responsibility areas expanded, and with one stakeholder "NDDOT Operations" selected in one role and responsibility area "Freeway Management for ND Statewide". As can be seen on the right side of the figure, the analyst drafted two statements of roles and responsibilities for this stakeholder in this role and responsibility area. Table 5 shows the partial roles and responsibilities report derived from this Turbo Architecture database. Note that the third row of this table has the roles and responsibilities illustrated in Figure 12.

Table 4: Vermont Statewide ITS Architecture Roles and Responsibilities

| Transportation Service | Stakeholder | Roles/ Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| Incident Management | Vtrans Operations Division |

|

| Vermont State Police |

|

|

| Municipal Public Safety |

|

|

| Regional Public Safety |

|

|

| Municipal Engineering Departments |

|

|

| Municipal Service Departments |

|

|

| CCTA/ GMTA/ Marble Valley |

|

Figure 12: Roles and Responsibilities View in Turbo Architecture

Table 5: Roles and Responsibilities Output from Turbo Architecture

| These tasks may be performed in parallel. |

|

|---|---|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

| PROCESS Key Activities |

|

|

INPUT Sources of Information |

|

|

OUTPUT Results from Process |

|

In this step, the tasks or activities (the "functions") that are performed by each ITS elements in the region are defined, documenting the share of the work that each ITS elements will do to provide the ITS services. (Recall that ITS elements can be associated with one or more subsystems or terminators from the National ITS Architecture. Functional requirements are associated with the ITS elements that are associated with one or more subsystems. Terminators do not have functional requirements in a regional ITS architecture. When we refer to ITS elements in this section, we are referring to ITS elements that are associated with one or more National ITS Architecture subsystems.)

Functional requirements are one of the required components of a regional ITS architecture as identified in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)5 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.5.

Functional requirements are one of the required components of a regional ITS architecture as identified in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)5 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.5.

Don't assume that the federal requirement for "system functional requirements" is an implied mandate to use structured analysis methods to develop each ITS element in the region. The functional requirements are high-level descriptions of what the ITS elements will do, not detailed design requirements. A region can choose to develop their ITS elements using object-oriented analysis, functional analysis, or whatever methodology they choose. The real objective of a regional ITS architecture is to clearly define interfaces and the responsibilities on both sides of the interface, and keep the implementation details (and methodology) used by any particular ITS element as transparent as possible.

Don't assume that the federal requirement for "system functional requirements" is an implied mandate to use structured analysis methods to develop each ITS element in the region. The functional requirements are high-level descriptions of what the ITS elements will do, not detailed design requirements. A region can choose to develop their ITS elements using object-oriented analysis, functional analysis, or whatever methodology they choose. The real objective of a regional ITS architecture is to clearly define interfaces and the responsibilities on both sides of the interface, and keep the implementation details (and methodology) used by any particular ITS element as transparent as possible.

Before writing the first functional requirement, determine the appropriate level of detail for the functional requirements. The level of detail is established for each regional ITS architecture based on the needs of the region. It's up to you!

While some regions may have unique objectives that demand more detailed specifications, very detailed functional requirements specifications within a regional ITS architecture can be counterproductive. Detailed specifications will increase the regional ITS architecture development and maintenance effort and they aren't really required until project definition begins. Unless there are special circumstances in your region, consider keeping the functional requirements specifications at a high level in the regional ITS architecture, and let the experts in the particular application area develop more detailed specifications when it is time to actually design and build projects.

In general, the functional requirements should be easy to write because they should follow directly from the ITS service decisions, operational concept, and interface choices made in other process steps. If many arbitrary decisions are required to complete the functional requirements, there is probably excessive detail in the requirements.

To begin to zero in on the right level of detail, think about the motivation for writing the functional requirements in the first place. You are trying to specify the things that an ITS element must do in order to "hold up its end of the bargain" in the regional ITS architecture. Even if it is high-level, the specification must still be complete. That is, it must list all the things that the ITS element must do. Also, it shouldn't list things that the ITS element is not required to do.

Let's consider an example where the stakeholders have decided that the State DOT TMC will make CCTV camera images available to several different operational users in the region. An extremely high level specification for the State DOT TMC could be that the TMC "shall manage traffic". This functional requirement is clearly too vague because it doesn't tell the State DOT that it has to share CCTV camera images, and it may also imply that the State DOT should perform traffic management functions that were never intended. On the other extreme, the specification might go too far and start to identify performance requirements or specify technology. The functional requirements should only specify WHAT the ITS element has to do; they should not specify performance (how fast, how many) or how the ITS element will implement this capability. An appropriate set of functional requirements for this example might be:

Another consideration is the scope or visibility of the requirements. Consider limiting the requirements to functions that have regional impact. Returning to the CCTV camera image example, the state DOT may also want to save camera images for a limited time for its own internal purposes and then discard them. This functionality does not have to be specified in the regional ITS architecture because it has no impact beyond the State DOT. If the State DOT does not implement this function, there will be no negative impact on the ITS integration for the region. Following this guideline, most of the functions that will be specified will focus on supporting interfaces between ITS elements.

Another consideration is the scope or visibility of the requirements. Consider limiting the requirements to functions that have regional impact. Returning to the CCTV camera image example, the state DOT may also want to save camera images for a limited time for its own internal purposes and then discard them. This functionality does not have to be specified in the regional ITS architecture because it has no impact beyond the State DOT. If the State DOT does not implement this function, there will be no negative impact on the ITS integration for the region. Following this guideline, most of the functions that will be specified will focus on supporting interfaces between ITS elements.

As a rule of thumb, an ITS elements functional requirements and interface definition should be specified at about the same level of detail. For example, an ITS element that generates and receives 10 different information flows might include about the same number of functional requirements that describe the high-level functions that are performed to exchange this information. As will be seen in Section 5, the architecture flows defined by the National ITS Architecture represent the typical level of detail used in regional ITS architecture interface definitions. For example, "incident information" is an architecture flow that is used in most regional ITS architectures. Since the architecture flow identifies incident information in general, the functional requirements should be at about the same level of detail and generally specify each ITS element's responsibility for incident information sharing. The requirements need not specify more detailed functions (e.g., who will time stamp the incident, how will a measure of incident severity be assigned and modified) that deal with more detailed components of a particular information flow. To improve consistency in the level of detail between functional requirements and interface definition, the architect may iterate between the two process steps. This iteration is a normal part of the process.

As a rule of thumb, an ITS elements functional requirements and interface definition should be specified at about the same level of detail. For example, an ITS element that generates and receives 10 different information flows might include about the same number of functional requirements that describe the high-level functions that are performed to exchange this information. As will be seen in Section 5, the architecture flows defined by the National ITS Architecture represent the typical level of detail used in regional ITS architecture interface definitions. For example, "incident information" is an architecture flow that is used in most regional ITS architectures. Since the architecture flow identifies incident information in general, the functional requirements should be at about the same level of detail and generally specify each ITS element's responsibility for incident information sharing. The requirements need not specify more detailed functions (e.g., who will time stamp the incident, how will a measure of incident severity be assigned and modified) that deal with more detailed components of a particular information flow. To improve consistency in the level of detail between functional requirements and interface definition, the architect may iterate between the two process steps. This iteration is a normal part of the process.

Functional requirements do not have to be written for every element in the inventory. As discussed in section 4.1, an inventory will normally include elements on the boundary of ITS that don't directly provide transportation services, but do exchange information with ITS elements. The classic example of an inventory element that is on the boundary is a financial institution that interfaces with ITS elements to support financial transactions. In general, a regional ITS architecture should include functions for ITS elements and should not include functions for ITS elements on the boundary.

An architectural boundary must be established to determine where functional requirements are needed. There are several ways to establish this boundary.

Security Considerations

In conjunction with functional requirements definition, security requirements can also be defined that identify security constraints and functions that will protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the connected systems and the data that will pass between them. The initial security requirements will be iterated and refined in subsequent steps as the regional architecture is fully defined and implemented in stepwise fashion, project by project. In general, the security requirements included in the regional ITS architecture will focus on those requirements associated with system integration and sharing of data between systems. Each individual system will still have responsibility for protecting the systems and data within their own domain. These internal system requirements are normally not the focus of the regional ITS architecture.

In conjunction with functional requirements definition, security requirements can also be defined that identify security constraints and functions that will protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the connected systems and the data that will pass between them. The initial security requirements will be iterated and refined in subsequent steps as the regional architecture is fully defined and implemented in stepwise fashion, project by project. In general, the security requirements included in the regional ITS architecture will focus on those requirements associated with system integration and sharing of data between systems. Each individual system will still have responsibility for protecting the systems and data within their own domain. These internal system requirements are normally not the focus of the regional ITS architecture.

The National ITS Architecture is a good source for functional requirements that may be selectively used in a regional ITS architecture. The physical architecture includes general descriptions for each subsystem that provide an overall summary of what ITS elements do. At the next level of detail, equipment packages include more precise descriptions of the functionality required for each service that a subsystem supports. Each equipment package also includes a set of functional requirements that can be adopted as is or modified to meet the specific needs of the region. All levels of descriptions are linked in the hypertext architecture on the web site and CD, allowing easy navigation between the levels of detail. The National ITS Architecture is available on CD-ROM and on-line at http://www.its.dot.gov/arch/index.htm.

The National ITS Architecture is a good source for functional requirements that may be selectively used in a regional ITS architecture. The physical architecture includes general descriptions for each subsystem that provide an overall summary of what ITS elements do. At the next level of detail, equipment packages include more precise descriptions of the functionality required for each service that a subsystem supports. Each equipment package also includes a set of functional requirements that can be adopted as is or modified to meet the specific needs of the region. All levels of descriptions are linked in the hypertext architecture on the web site and CD, allowing easy navigation between the levels of detail. The National ITS Architecture is available on CD-ROM and on-line at http://www.its.dot.gov/arch/index.htm.

Turbo Architecture directly supports functional requirements specification based on the selection of market packages and allocation of ITS elements to those market packages. Turbo will help the analyst select "functional areas" for each ITS element that exactly correspond to National ITS Architecture equipment packages. For each functional area that is selected, a menu of functional requirements are presented that can be selected and/or modified , based on actual stakeholder needs.

Turbo Architecture directly supports functional requirements specification based on the selection of market packages and allocation of ITS elements to those market packages. Turbo will help the analyst select "functional areas" for each ITS element that exactly correspond to National ITS Architecture equipment packages. For each functional area that is selected, a menu of functional requirements are presented that can be selected and/or modified , based on actual stakeholder needs.

High-level textual functional requirements can be prepared that describe WHAT each ITS element does to support the ITS services that have been selected for the region. The requirements are a list of "shall statements" that define each major function that is performed by the ITS element, focusing on those functions that have implications for regional integration..

This section presents two examples of functional requirements, one example based on using equipment package functional requirements without editing, and another that uses Turbo to customize the functional requirements.

Example 1: Functional Requirements directly from Market Package selected Equipment Packages

Earlier, in Figure 11, we observed the ITS Element Report for the Gulf Breeze Field Equipment ITS Element in the Florida DOT District 3 regional ITS architecture. Based on this ITS elements mapping as a Roadway Subsystem, and the market packages with which this ITS element is associated, the five Equipment Packages were selected in the bottom of this report. Each of these equipment packages then have a set of functional requirements associated with their own reports. See for example Figure 13 which shows the equipment package report for the first equipment package "Roadway Basic Surveillance". This report shows the 5 functional requirements associated with this equipment package taken directly from the National ITS Architecture.

Figure 13: Equipment Package Report showing Functional Requirements

Example 2: High-Level Functional Requirements using Turbo Architecture

In Figure 14, we are viewing the requirements tab in Turbo Architecture using the ND Statewide ITS Architecture. Here, functional areas have been automatically selected based on Market Packages and ITS elements that have been selected for some of the functional areas. In this example, the "Collect Traffic Surveillance" functional area has the NDDOT Operations" ITS element selected. Highlighting the NDDOT Operations element and selecting the Requirements button brings up the screen in Figure 15, where the analyst can select from the menu of related functional requirements. In this example, the analyst has only chosen two of the nine possible functional requirements.

Figure 14: Functional Areas Selection in Turbo Architecture

Figure 15: Functional Requirements Selection in Turbo Architecture

Finally, the fragment of the Functional Requirements report from the ND Statewide final report is shown in Figure 16. The selected functional requirements from Figure 15 are reported here.

Figure 16: Turbo Architecture Functional Requirements Report (partial)

TOC Previous Page Next Page