Regional ITS Architecture Guidance Document

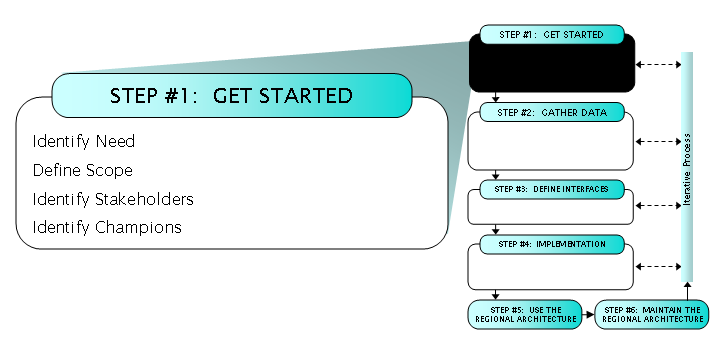

This section describes the first step in the regional ITS architecture development process — "Get Started".

The regional ITS architecture effort begins with a focus on the institutions and people involved. Based on the scope of the region, the relevant stakeholders are identified and a plan to engage them is developed, one or more champions are identified, the team that will be involved in architecture development is organized, and the overall development effort is planned with particular focus on outreach and consensus building.

In this section, the four "Get Started" process tasks are described in more detail. Each task description begins with a one page summary that is followed by additional detail on the process, relevant resources and tools, a general description of the associated outputs, and example outputs where they are available. Each task description also includes tips and cautionary advice that reflect lessons that have been learned in development of regional ITS architectures over the past several years.

| These tasks may be performed in parallel. |

|

|---|---|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

| PROCESS Key Activities |

Assess Need and Ability

|

| INPUT Sources of Information |

|

| OUTPUT Results from Process |

|

In this step, the decision to develop a regional ITS architecture is made. Through this decision process, the development and maintenance of a regional ITS architecture is established as a shared objective by the transportation planning and operating agencies in the region.

Requirements for developing a regional ITS architecture are identified by FHWA Rule 940.9 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.

Requirements for developing a regional ITS architecture are identified by FHWA Rule 940.9 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.

A regional ITS architecture is required by the FHWA Rule/FTA Policy for regions that have deployed, or will be deploying, ITS projects. An examination of the deployed ITS systems, the plans for future ITS deployments, and system integration opportunities in the region will establish if the rule/policy applies and a regional ITS architecture is required. While the rule/policy establishes a clear "requirement" for a regional ITS architecture for many regions, the real "need" for a regional ITS architecture is based more on its utility in ITS project planning and implementation.

The most important reason to develop a regional ITS architecture is that it can help the region to efficiently plan for and implement more effective ITS systems. Thus, the ultimate objective is not to develop a regional ITS architecture that complies with a federal rule or policy, but to develop a regional ITS architecture that can really be used by the region to guide ITS implementation. A regional ITS architecture that includes all the products specified by the rule/policy but is never used by the region is not of real benefit to the region or US DOT. To meet the requirements of the rule/policy, the regional ITS architecture must be used to measure conformance of ITS projects on an on-going basis and be maintained as regional ITS requirements evolve.

The decision to proceed then should actually be based on a clear understanding and commitment by planning agencies, operating agencies, and key decision makers in the region that a regional ITS architecture is needed and will be put to good use. This implies that a decision to proceed should be accompanied by significant outreach and education on the benefits of ITS and system integration and the important role that a regional ITS architecture can play in developing these integrated systems.

There are many good resources available that can support the outreach and education effort that may be required to realize the benefits of a regional ITS architecture. USDOT has published an "ITS Resource Guide" that lists over 300 documents, web sites, training courses, software tools, and points of contact covering all aspects of ITS, including the National ITS Architecture and regional ITS architectures. An online version of this guide is available at http://www.its.dot.gov/guide.htm.

There are many good resources available that can support the outreach and education effort that may be required to realize the benefits of a regional ITS architecture. USDOT has published an "ITS Resource Guide" that lists over 300 documents, web sites, training courses, software tools, and points of contact covering all aspects of ITS, including the National ITS Architecture and regional ITS architectures. An online version of this guide is available at http://www.its.dot.gov/guide.htm.

| These tasks may be performed in parallel. |

|

|---|---|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

| PROCESS Key Activities |

Define the Regional ITS Architecture Scope

|

| INPUT Sources of Information |

|

| OUTPUT Results from Process |

|

The process of developing a regional ITS architecture begins with a definition of the region. The fundamental scope for the regional ITS architecture is established with the definition produced in this step.

The general scope of a regional ITS architecture can be defined in three ways:

Don't invest too much time trying to define the region perfectly the first time. Remember that developing a regional ITS architecture is an iterative process, and the definition of the region can be adjusted as the regional ITS architecture begins to take shape. The stakeholders should make a first cut at defining the region and then update the geographic area, timeframe, and service scope as new stakeholders are identified, new integration opportunities are considered, and the ultimate uses for the regional ITS architecture are discussed in more detail.

Don't invest too much time trying to define the region perfectly the first time. Remember that developing a regional ITS architecture is an iterative process, and the definition of the region can be adjusted as the regional ITS architecture begins to take shape. The stakeholders should make a first cut at defining the region and then update the geographic area, timeframe, and service scope as new stakeholders are identified, new integration opportunities are considered, and the ultimate uses for the regional ITS architecture are discussed in more detail.

Geographic Area

Ideally, the geographic scope of a region should be established so that it encompasses all systems that should be integrated together. In practice, it is sometimes difficult to determine where to draw the line so that the regional ITS architecture is inclusive without expanding to the point that the effort becomes unmanageable and consensus is difficult to achieve. While this is frequently called a "geographic" area, it is usually a political map that is being partitioned, defining a region along existing institutional boundaries.

The rule/policy states that metropolitan areas must consider the metropolitan planning area (MPA) as a minimum size for a region. The MPA is a good place to start since this boundary normally encompasses most integration opportunities and it coincides with the geographic region used for transportation planning. If the MPA is not the right boundary for a metropolitan regional ITS architecture, than a different geographic area can be specified, with rationale.

The rule/policy states that metropolitan areas must consider the metropolitan planning area (MPA) as a minimum size for a region. The MPA is a good place to start since this boundary normally encompasses most integration opportunities and it coincides with the geographic region used for transportation planning. If the MPA is not the right boundary for a metropolitan regional ITS architecture, than a different geographic area can be specified, with rationale.

Service boundaries and special conformity boundaries should also be taken into consideration when determining the regional boundary:

Service Boundaries: Regional transportation agencies and other stakeholders each have geographic areas that they serve (e.g., transit services, toll authorities, etc.). These service boundaries should be considered when defining the geographic boundary for the regional ITS architecture. In metropolitan areas, these service boundaries may go outside the metropolitan planning area and influence the regional ITS architecture boundary.

Special Conformity Boundaries: In regions where there are special conformity issues like Air Quality, special conformity boundaries may also be considered. For example, ITS projects that are implemented to meet air quality goals within an air quality conformance boundary may require integration with other projects in the region. This suggests that the air quality conformance boundary may also be considered in establishing the geographic area covered by the regional ITS architecture.

Also consider the scope of other regional ITS architectures when defining the boundary. Where there are adjoining or overlapping regional ITS architectures, coordinate with the other region(s) to reach agreement on how common systems or interfaces will be represented in the two (or more) regional ITS architectures. For example, many states have created statewide ITS architectures that must be taken into account by the metropolitan area architecture(s) in those states. A few agencies have also created their own agency architectures that focus on internal agency interfaces, creating additional levels of architecture definition that should be taken into account in establishing architecture scope.

Special care is required when regional ITS architectures do overlap. Caution should be used whenever the same ITS element or interface is included in more than one regional ITS architecture. Unless automated methods like a relational database or Turbo Architecture are used, it is almost certain that some difference or ambiguity will arise in the two (or more) representations of the same architecture definition. Whenever possible, it is a good idea to define the ITS element or interface in one architecture and reference the one "authoritative" definition in all other regional ITS architectures.

Special care is required when regional ITS architectures do overlap. Caution should be used whenever the same ITS element or interface is included in more than one regional ITS architecture. Unless automated methods like a relational database or Turbo Architecture are used, it is almost certain that some difference or ambiguity will arise in the two (or more) representations of the same architecture definition. Whenever possible, it is a good idea to define the ITS element or interface in one architecture and reference the one "authoritative" definition in all other regional ITS architectures.

Timeframe

The regional ITS architecture should look far enough into the future so that it serves its primary purpose of guiding the efficient integration of ITS systems over time. While there is no required minimum, the most appropriate timeframe can be established based on how the regional ITS architecture will be used. Making the timeframe too short reduces the value of the regional ITS architecture as a planning tool. Making the timeframe too long increases the effort involved since very long range forecasts are difficult to make and subject to reevaluation and change.

A rough 5-, 10-, or 20-year approximation of the timeframe is enough to begin the process. The initial timeframe can then be reevaluated and changed as the regional ITS architecture takes shape.

A rough 5-, 10-, or 20-year approximation of the timeframe is enough to begin the process. The initial timeframe can then be reevaluated and changed as the regional ITS architecture takes shape.

As the regional ITS architecture is defined, the timeframe is normally a secondary consideration when determining whether to include a particular ITS element or interface. It is usually best to include the interfaces that are clearly supported by the stakeholders, even if these consensus interfaces push the envelope of the timeframe that was initially selected. In other words, the timeframe should be adjusted as necessary to match the vision of the stakeholders. It shouldn't be used to precisely constrain the stakeholders to near-term options since it is difficult to anticipate exactly when a well-supported idea will be implemented. Viable integration opportunities should be included in the regional ITS architecture and then reevaluated periodically as the regional ITS architecture is maintained over time.

Service Scope

While specific identification of ITS services occurs later in the process, general decisions can be made immediately based on the scope of other regional ITS architectures. For example, if a statewide ITS architecture is defining commercial vehicle services, the 511 traveler information system, and the electronic toll collection system for the state, then any other regional ITS architectures in the state may decide to reference the statewide architecture for these services.

Avoid defining the same ITS services in multiple regional ITS architectures. The redundancy will cause difficulty in maintaining regional ITS architectures so that they are always consistent and complicate architecture use in the region.

Avoid defining the same ITS services in multiple regional ITS architectures. The redundancy will cause difficulty in maintaining regional ITS architectures so that they are always consistent and complicate architecture use in the region.

Security Considerations

A high-level security policy statement may be included in the formative scope of the regional ITS architecture that will guide architecture development in subsequent steps. Establishing the basic need for security at the outset is particularly important where regional ITS architectures rely on participation and support from public safety, emergency management, and other organizations where security is critical. Different organizations will be willing to accept different levels of risk; the security policy statement is an initial shared statement that can encourage organizations to participate in the regional ITS architecture development and subsequent integration projects.

A high-level security policy statement may be included in the formative scope of the regional ITS architecture that will guide architecture development in subsequent steps. Establishing the basic need for security at the outset is particularly important where regional ITS architectures rely on participation and support from public safety, emergency management, and other organizations where security is critical. Different organizations will be willing to accept different levels of risk; the security policy statement is an initial shared statement that can encourage organizations to participate in the regional ITS architecture development and subsequent integration projects.

The definition of a region will specify the geographic area of coverage, typically using a map and a supporting textual description. The timeframe and service scope of the regional ITS architecture can also be defined to more completely document the scope of the region.

Many different types of "regions " have been defined in the regional ITS architectures that have been developed to date. Architectures have been developed for all of the following types of geographic areas:

The last category is defined by a particular service or group of services. Service regions include tourist areas like the Greater Yellowstone region and international border areas like Western New York and Southern Ontario (the "Buffalo-Niagara Bi-National Regional ITS Architecture"). The service region may have a specific scope of ITS Services; for example, a larger regional ITS architecture that focuses on traveler information.

Two examples illustrate some of the types of regions that can be defined. The first example region was defined by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC), which is the Metropolitan Planning Organization for the nine-county Philadelphia region. The region is essentially the nine-county MPO region expanded to include interfaces to ITS systems outside the region. The region is shown in the map in Figure 1.

Figure 2: Regional ITS Architecture scope for the Delaware Valley RPCThe second example, illustrated in Figure 2, shows the approximate geographic scope of three regional ITS architectures under development in the central valley in Northern California and adjacent mountain regions. The Sacramento Regional ITS Architecture covers the Sacramento metropolitan area and surrounding cities including all of Sacramento County, portions of Yolo County and portions of Placer County. The Tahoe Gateway Counties ITS Strategic Deployment Plan includes Nevada County, Sierra County, Placer County and El Dorado County. The Tahoe Basin ITS Strategic Plan incorporates parts of two states (California and Nevada) and five counties (Carson City, Douglas, El Dorado, Placer and Washoe) and the town of Truckee, located in Nevada County. The boundaries of these architectures overlap, requiring a commitment and open lines of communication between the three projects.

| These tasks may be performed in parallel. |

|

|---|---|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

| PROCESS Key Activities |

Outreach to Stakeholders

|

| INPUT Sources of Information |

|

| OUTPUT Results from Process |

|

Figure 3 : Adjacent/Overlapping Regions

The success of the regional ITS architecture depends on participation by a diverse set of stakeholders. In this step, the stakeholders in the regional surface transportation system are identified and the process of encouraging their participation in the regional ITS architecture development process is initiated.

Identification of participating agencies and stakeholders is one of the required components of a regional ITS architecture as identified in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)2 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.2.

Identification of participating agencies and stakeholders is one of the required components of a regional ITS architecture as identified in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)2 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.2.

Regions will vary dramatically in the degree to which the surface transportation system stakeholders are aware of ITS. In regions that have already implemented substantial ITS systems, the stakeholders have already been working together on many of the issues that will be addressed during regional ITS architecture development. As a result, these regions usually have existing ITS committees that will be a natural forum to kick-off the regional ITS architecture development.

Other regions will require more significant education and outreach efforts about ITS in general and the merits of a regional ITS architecture in particular to assemble and motivate enough stakeholders. When preparing education and outreach material to introduce stakeholders to the regional ITS architecture, it is a good idea to use local project examples that may already be familiar. If local examples are not available, a variety of excellent material is available from USDOT and other sources.

Educating the right people is important – frequently the education and outreach efforts will target the management levels in an organization where decisions can be made to commit valuable personnel resources to support the architecture development effort. Without management support, it will be difficult or impossible for those with a working knowledge of ITS in the region to participate effectively in the regional ITS architecture effort.

It is often best to start with a core stakeholder group and then add participants to the core group over time. The core stakeholders group would itself be a diverse group with representation from each major agency and from both planners and system operators. This core group provides continuity to the development effort and an important set of contacts for the champion(s) and architecture developer(s). Including too many stakeholders at the start can hinder regional ITS architecture development progress and discourage people with limited vested interest in the process. Although the architecture effort should be very inclusive, a region may have better initial success if they are able to build consensus among the stakeholders that plan/own/operate ITS systems first before adding others into the decision making process.

It is often best to start with a core stakeholder group and then add participants to the core group over time. The core stakeholders group would itself be a diverse group with representation from each major agency and from both planners and system operators. This core group provides continuity to the development effort and an important set of contacts for the champion(s) and architecture developer(s). Including too many stakeholders at the start can hinder regional ITS architecture development progress and discourage people with limited vested interest in the process. Although the architecture effort should be very inclusive, a region may have better initial success if they are able to build consensus among the stakeholders that plan/own/operate ITS systems first before adding others into the decision making process.

Figure 3 shows a conceptual view of how stakeholders are added over time to the core stakeholder group. The core group is used to kick-off the effort. The number of active, participating stakeholders increases as the architecture development effort begins to generate more detailed and varied products that require broad review and support. The number of active stakeholders may then begin to taper off as reviews are completed, comments are incorporated, and "completed " regional ITS architecture products are published. This same strategy of engagement can be used, but probably on a smaller scale, for periodic maintenance activities that follow.

Figure 4 : Stakeholder Identification and Involvement Over TimeWhile the number of active stakeholders begins to taper as the workload is reduced, the graph on the right shows that the total number of stakeholders will continue to increase over time, as different specialties and agencies participate in different parts of the architecture and different steps in the process. The perspective of the graph on the right is that once you are a stakeholder, you are always a stakeholder, although you may not actively participate beyond a specific milestone in the process. Over time, all relevant stakeholders in the region are engaged, just not all at once at the beginning of the architecture development effort.

If it is decided to initially limit the number of participants to a core group as depicted in Figure 3, set a timeframe to add others so that the architecture reflects the broader interests of the region. Table 1 in section 0 provides a list of potential stakeholders to consider.

As additional stakeholders are added to the process, it may be a good idea to retain a core group that meets regularly and have a broader group that is included at selected milestones in the regional ITS architecture development. It is critical that all stakeholders participate enough in the process that they understand the architecture and feel some ownership of the process and the regional ITS architecture that is developed. It is important to continually encourage and validate participation of stakeholders in the development process.

It is also important to focus stakeholder participation appropriately. For example, both planners and system operators will participate in the process, but with substantially different focus. System operators may be more interested in the operational concepts, functional requirements, and interface definitions, while the planners may have more substantial input while identifying transportation needs and services and project sequencing. Other individuals with specialized knowledge will be needed to assist in development of the list of agreements and list of required ITS standards. As the "stakeholder roster " is developed, consider the various areas of expertise that are required and use your stakeholder resources selectively. Different stakeholders should be engaged in different parts of the process, consistent with their expertise and interests.

It is also important to focus stakeholder participation appropriately. For example, both planners and system operators will participate in the process, but with substantially different focus. System operators may be more interested in the operational concepts, functional requirements, and interface definitions, while the planners may have more substantial input while identifying transportation needs and services and project sequencing. Other individuals with specialized knowledge will be needed to assist in development of the list of agreements and list of required ITS standards. As the "stakeholder roster " is developed, consider the various areas of expertise that are required and use your stakeholder resources selectively. Different stakeholders should be engaged in different parts of the process, consistent with their expertise and interests.

Encouraging broad participation from many agencies, companies, and special interests in the region will occasionally bring people into the process who aren't really stakeholders in the regional transportation system. If the representative doesn't have, or plan to have, a system that should be integrated within the architecture timeframe or an interest in the surface transportation system as a whole (e.g., planners, the tourist industry, other special interests), then the representative is probably NOT really a stakeholder, will have little to contribute, and may ultimately grow frustrated with the process. It is best to understand the role of each potential new stakeholder in the surface transportation system at the outset and determine how they may contribute before significant time is invested. The objective is to be inclusive without wasting the time of those who do not have a vested interest.

Recognize and respect that everyone's time is limited. Draw participants into the process without bogging them down. Some useful techniques to encourage people with demanding schedules to participate are to make sure everyone gets plenty of time to review documents, and schedule short meetings with teleconferencing options. This will help retain participants that may otherwise give up on the architecture effort due to other commitments.

Recognize and respect that everyone's time is limited. Draw participants into the process without bogging them down. Some useful techniques to encourage people with demanding schedules to participate are to make sure everyone gets plenty of time to review documents, and schedule short meetings with teleconferencing options. This will help retain participants that may otherwise give up on the architecture effort due to other commitments.

Many good education and outreach resources are available to support efforts to encourage stakeholder participation in ITS-related efforts. USDOT has published an "ITS Resource Guide " that lists over 300 documents, web sites, training courses, software tools, and points of contact covering all aspects of ITS, including ITS architecture. An online version of this guide is available at http://www.its.dot.gov/guide.htm.

Many good education and outreach resources are available to support efforts to encourage stakeholder participation in ITS-related efforts. USDOT has published an "ITS Resource Guide " that lists over 300 documents, web sites, training courses, software tools, and points of contact covering all aspects of ITS, including ITS architecture. An online version of this guide is available at http://www.its.dot.gov/guide.htm.

Applicable National ITS Architecture resources include a training course and technical information that has been used to assist in identification of stakeholders in the past. The National ITS Architecture training course is provided by the National Highway Institute (Course # 137013, http://www.nhi.fhwa.dot.gov/). The subsystems and terminators defined in the physical architecture provide a good categorization of the various systems and stakeholders that can be considered in developing a list of stakeholders for the regional ITS architecture development. To access an on-line version of the Architecture, visit http://www.its.dot.gov/arch/index.htm.

Applicable National ITS Architecture resources include a training course and technical information that has been used to assist in identification of stakeholders in the past. The National ITS Architecture training course is provided by the National Highway Institute (Course # 137013, http://www.nhi.fhwa.dot.gov/). The subsystems and terminators defined in the physical architecture provide a good categorization of the various systems and stakeholders that can be considered in developing a list of stakeholders for the regional ITS architecture development. To access an on-line version of the Architecture, visit http://www.its.dot.gov/arch/index.htm.

Stakeholder lists may be entered directly into Turbo Architecture. Each stakeholder includes a name and a description and a variety of other information. Turbo can generate a stakeholder report and export stakeholder information to support the stakeholder output described in section 0.

Stakeholder lists may be entered directly into Turbo Architecture. Each stakeholder includes a name and a description and a variety of other information. Turbo can generate a stakeholder report and export stakeholder information to support the stakeholder output described in section 0.

The list of stakeholders identified in Table 1 includes the range of stakeholders that have participated in regional ITS architecture development efforts around the country. The table makes a good checklist of possible stakeholders that may be involved in your regional ITS architecture.

Table 1: Candidate Stakeholders

| Transportation Agencies |

|

|---|---|

| Transit Agencies/Other Transit Providers |

|

| Planning Organizations |

|

| Public Safety Agencies |

|

| Other Agency Departments |

|

| Activity Centers |

|

| Fleet Operators |

|

| Travelers |

|

| Private Sector |

|

| Other Agencies |

|

This output identifies stakeholders who participated in the development of the regional ITS architecture by:

The purpose of this output is to record the stakeholder participation in the development of the regional ITS architecture and document the consensus process that was used in the regional ITS architecture development.

The actual documentation can take many forms, but a straightforward approach is to build a simple table or database with fields identifying the agency, company or interest group, transportation area, and possibly key participant contact information. This table can then be sorted by agency, company or interest group to check if each agency, company or interest group has adequate representation in the regional ITS architecture consensus development process.

Table 2 is a basic list of stakeholders that was prepared for an ITS architecture for the Franklin Tennessee Traffic Operations Center (TOC). It identifies each stakeholder agency that is related to the TOC and the systems that relate to each stakeholder agency. This is the complete stakeholder list for this small regional ITS architecture. The list of stakeholders will be considerably larger than this for most metropolitan regions.

Table 2: Franklin, TN TOC Stakeholders

| Stakeholder Name | Responsible for these systems in the Architecture |

|---|---|

| City of Franklin Engineering Department | Storm Water Management System |

| Franklin TOC_Personnel | |

| Franklin TOC_Roadside Equipment | |

| Franklin Parking Management System | |

| Franklin TOC | |

| Franklin Police Department | Emergency Vehicles |

| Franklin Police Dispatch_Personnel | |

| Weather Service | |

| Franklin Police Dispatch | |

| Tennessee DOT | Nashville Regional Transportation Management Center |

| Franklin Transit | Franklin Transit System |

| Transit Vehicles | |

| TMA Group | Franklin TMA Kiosks |

| City of Franklin Streets Department | Construction and Maintenance |

| Community Access Television | Media |

| City of Franklin | Event Promoters |

| Franklin Website | |

| City of Murfreesboro | Murfreesboro TOC |

| Traveling Public | User Personal Computing Devices |

| Williamson County | Williamson County Emergency Management System |

| Nashville MPO | Regional Planning System |

| These tasks may be performed in parallel. |

|

|---|---|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

| PROCESS Key Activities |

Looking for Champion(s)

|

|

INPUT Sources of Information |

|

|

OUTPUT Results from Process |

|

In this step, the champion(s) that will lead the regional ITS architecture development effort are identified. The champion(s) drive the process that must occur in order to develop a regional ITS architecture and build consensus at each step of the development. Without strong leadership, consistent meetings and a plan for completion of tasks, many of the participants will quickly become busy with other daily responsibilities.

Many regions have already developed a team of ITS stakeholders that meet on a regular basis. Chances are that the champion(s) have already been identified by the fact that they are leading the regional efforts through an ITS Task Force, Technical Advisory Committee or the fact that they are already leading a major ITS project in the region. Adding regional ITS architecture consensus building to whatever "hat " these people are already wearing will be a natural transition. The process of identifying a champion or champion(s), and developing a task force to put the regional ITS architecture together should be woven into the existing regional planning process for ITS if one is already underway.

Champions are usually not voted-in; they are selected "on the job " in the course of working together. In many regions, a single champion will be identified. If there are several people who rise to the occasion, several champions can be identified that take turns leading the meetings or agree upon some shared responsibilities that will keep everyone engaged. A champion's skills include:

The skill level that is needed in each area will vary depending on the technical and institutional maturity of the region. A more technically mature region may have many people with existing knowledge of the National ITS Architecture, but require increased skills in consensus building to pull various interests together. In institutionally mature areas that are growing in ITS technology, it may be a strong vision that guides the process. All of the identified skills are important for a strong successful champion along with the knowledge of when to use them.

No one individual is likely to possess all the knowledge and skills required to develop a regional ITS architecture. To be successful, the champion(s) must draw on the knowledge and skills of a diverse set of stakeholders. The champion is primarily a facilitator and manager and is not normally the one that actually defines the architecture – the stakeholders are.

A Champion must be a Stakeholder. It would be very difficult, if not impossible, for someone who did not have a vested interest in the outcome to be the champion for a regional ITS architecture development effort. A stakeholder who is already recognized in the region will best be able to take ownership and invest the time necessary to manage the regional ITS architecture development. FHWA, FTA, consultants, vendors and others are great participants, consultants may even do a lot of the detailed analysis and legwork in a regional ITS architecture effort, but for regional long-term benefit, they should not be champions.

Identifying more than one Champion from varying backgrounds and disciplines (e.g., public safety, transit, state DOT, city and/or county traffic engineering) can be a benefit. A small group of people with diverse backgrounds and contacts can strengthen the regional ITS architecture product by improving stakeholder participation, encouraging agency buy-in, and facilitating access to the information and resources necessary to support architecture development. Where several champions are identified, they may form a steering committee (which could also include representation from others such as FHWA/FTA) that manages by consensus or advises and supports a leader who actually manages the development and maintenance effort.

Identifying more than one Champion from varying backgrounds and disciplines (e.g., public safety, transit, state DOT, city and/or county traffic engineering) can be a benefit. A small group of people with diverse backgrounds and contacts can strengthen the regional ITS architecture product by improving stakeholder participation, encouraging agency buy-in, and facilitating access to the information and resources necessary to support architecture development. Where several champions are identified, they may form a steering committee (which could also include representation from others such as FHWA/FTA) that manages by consensus or advises and supports a leader who actually manages the development and maintenance effort.

Section 0 introduced the idea of a core stakeholder group that would be involved throughout the architecture development effort. This group might be the small group of "champions " described in the previous paragraph, or it could be a larger group. No one model will encompass all regional ITS architecture development efforts. Each region must decide how they wish to organize their efforts. The key is that there is a group of stakeholders who plays a key role throughout the architecture development effort.

Champions will probably come and go over the evolution of developing and maintaining the regional ITS architecture, and certainly will change over the life of regional ITS system implementation and expansion. The task of the Champion, like other leadership responsibilities, takes significant time. Dividing the work among a few champions will limit the turnover and ease the transition when one person leaves. It is important that good meeting minutes and records of action items are kept so that new champions will have some guidance regarding when, where, and why decisions were made.

Champions will probably come and go over the evolution of developing and maintaining the regional ITS architecture, and certainly will change over the life of regional ITS system implementation and expansion. The task of the Champion, like other leadership responsibilities, takes significant time. Dividing the work among a few champions will limit the turnover and ease the transition when one person leaves. It is important that good meeting minutes and records of action items are kept so that new champions will have some guidance regarding when, where, and why decisions were made.

Champions are identified based on the people involved, the priorities of the participating agencies, and a range of other factors that are unique to each region. Because the factors involved are so specific to a region, it is unlikely that information on past champions will influence the selection of future champions in other regions. Nevertheless, it is interesting to look at the agency affiliation and titles of champions that have been identified. Table 3 shows some of the champions that have supported regional ITS architecture efforts in recent years. The table shows that a significant majority of champions have worked for either the state DOT or MPO.

Table 3: Regional ITS Architecture Champions

| Region | Champion |

|---|---|

| Albany, NY | Assistant Regional Traffic Engineer – NYSDOT |

| Atlanta, GA | Senior Planner – Atlanta Regional Commission |

| Austin, TX | Traffic Engineer – TXDOT Austin |

| Chicago, IL | ITS Program Manager – IDOT |

| Cleveland, OH | Work Zone & Traffic Control Engineer – Ohio DOT |

| Detroit, MI | Senior Engineer – SEMCOG |

| Hartford, CT | Supervising Engineer – ConnDOT |

| Honolulu, HI | Executive Director – Oahu Metropolitan Planning Organization |

| Indianapolis, IN | INDOT |

| Kansas City, KS | Manager, Transportation Programs – Mid-America Regional Council |

| Little Rock, AR | Engineer – Metroplan |

| Long Island, NY | Inform ODS Director – NYSDOT R-10 |

| Milwaukee, WI | TOC Assistant Manager, WisDOT |

| Oklahoma City, OK | Associate Planner, ACOG |

| Omaha, NE | Transportation Technology Engineer – Nebraska Department of Roads |

| Pittsburgh, PA | Transportation Planner, Southwestern Pennsylvania Regional Planning Commission |

| Portland, OR | Regional Traffic Engineer – ODOT |

| Providence, RI | TMC Manager – RIDOT |

| Rochester, NY | ITS Coordinator – NYSDOT |

| Sacramento, CA | Senior Analyst – Sacramento Council of Governments |

| St. Louis, MO | TIC Manager – MoDOT |

| State College, PA | Risk Management/ITS Administrator – PennDOT 2-0 |