The Value of a Business Case in Mainstreaming TSMO

6. Business Cases and Findings from Other Industries

The business case for public-sector investments is often different from the private sector, including regulated industries. In the private sector, the primary beneficiary is often the owner, shareholder, investor, or lender who realizes gains from improved operations, which lead to growth in market share, revenue, and profitability. The business case is often made by showing a rate of return on the investment that justifies making the investment.

In the public sector, including most transportation agencies, the primary beneficiary of investments is the system user, including other public-sector entities (e.g., local agencies and first responders benefit from mobility improvements); however, investments are typically made by agencies that must compete with other agencies and community needs for investment funds. Competition also exists within an individual agency because of internal priorities.

There are similarities, however. Public- and private-sector entities must identify and quantify, to the extent possible, the needs or opportunities associated with investment alternatives. They must also demonstrate how these investments benefit the population served (i.e., the use case) or the investors, owners, and shareholders who make the investments.

This section discusses how select industries similar to transportation agencies make the business case for improving management and operations. Three industries are discussed: health care, electric utilities, and power generation. Each industry provides services instead of tangible products that are typically offered on demand rather than stored for later use or consumption. The transportation system has similarities and differences with these industries. Electric utilities and power distribution systems require continuous service along a fixed path of distribution lines. They cannot tolerate frequent interruptions or delays, so the capacity must be designed to accommodate the maximum demand and continue to do so under varying conditions. Transportation is also a vital need, but there is more flexibility in routes, modes, and schedules for some portion of users. Health care delivery shares common features of transportation, in that it deals with immediate demands (e.g., emergency departments), elective demand (i.e., scheduled to match the availability of services), and urgent but less critical demand.

Health Care

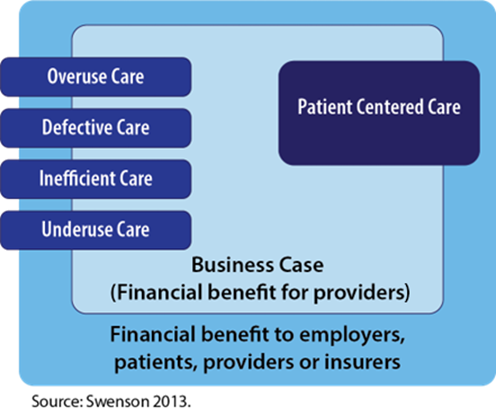

The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, developed a business case for multiple investments designed to reduce waste, improve efficiency, and improve the effectiveness of the care provided. (Swenson 2013) Figure 4 illustrates the framework used to develop the business case, focusing on the areas where benefits accrue to providers and patients. The focus areas include inappropriate use of resources (overuse, defective, and inefficient) and underuse of care, which results in subsequent health care needs that are more costly and complex.

Source: Federal Highway Administration.

Figure 4. Diagram. Quality improvement beneficiaries associated with health care business case.

In this diagram, undesirable care types include overuse care, defective care, inefficient care, and underuse care. By applying patient-centered care model, the business case is based on financial benefits for providers, employers, patients, and providers or insurers.

The study team at the Mayo Clinic developed solid business cases for improvements in orthopedic surgery and the cardiovascular outpatient clinic, which resulted in reduced waste. The business case was developed primarily through incremental implementation of proposed actions that were likely to reduce costs and improve patient outcomes. The results were then carefully monitored and compared to the baseline metrics. While one might hope to establish a solid business case prior to implementation, it is difficult to make reliable estimates prior to implementation. Ultimately, standardizing care processes resulted in $2.6 million annual savings in orthopedic surgery compared to the baseline metrics. Beyond reductions in cost, meaningful quality improvements included a 40-percent reduction in blood product utilization and reduced infection rates. In the 1-year period during which changes were implemented, the average length of stay decreased from 3.8 to 2.7 days, with a decline in hospital readmissions from an average of 3 percent to 2.6 percent. Staff satisfaction improved with no negative effect on patient satisfaction.

Similarly, improvements in the cardiovascular outpatient clinic resulted in increased physician fill rates from 70 to 92 percent, decreased cancellations and no-shows from 30 to 10 percent, reduced wait time to access appointments by 91 percent (from 33 to 3 days), and increased face time with providers from 240 to 285 minutes. The resources devoted to developing and implementing these improvements yielded a 5:1 return on investment.

Mayo Clinic’s Department of Finance developed guidelines for identifying the financial impact of investments and organized them into hard and soft impacts.

Hard impact has these general attributes:

- Effect on cash flow is definite.

- Effect on cash flow is readily quantifiable.

- Timing tends to be near term (i.e., months; maybe even 1–2 years, depending on project scope and duration).

- Items tend to have transaction-based evidence.

Soft impact has these general attributes:

- Effect on operations is identifiable; however, cash flow is indirectly impacted.

- Effect on cash flow is indefinite or not quantifiable.

- Timing tends to be long term (i.e., may require 1–2 years, or more, before cash flow impact is realized).

- Long-term impact is likely realizable.

The business case was made for each improvement based on the positive financial impact of identifiable and measurable improvements in patient care. The financial impact came largely from reducing waste and from avoiding adverse events to patients (e.g., falls and infections) that might extend their length of stay.

The primary takeaway for TSMO is that major improvements were achieved though incremental improvements in the way services were delivered, rather than through added capacity. These improvements required engaging stakeholders to gain a deep understanding of current procedures and looking for opportunities to standardize procedures to reduce waste and improve efficiency. The business case for TSMO often includes showing how TSMO strategies make more effective use of available capacity, and also how these strategies can improve the movement of goods and people through reduced delays and fewer incidents.

Electric Utilities

“Globally, the replacement and maintenance of utility infrastructure is providing the industry with an important opportunity to upgrade and modernize the electric network.” (Groark 2019) A similar statement could be made about transportation infrastructure, and many aspects of the business case for upgrading and modernizing electric utilities apply to transportation infrastructure and operations.

The business case in Groark (2019) is for a utility monitoring and diagnostic center that enables utility companies to identify current and imminent problems so that they can avoid catastrophic failures and allocate investment more efficiently. While similar to a traffic management center, in that it monitors system performance, the utility monitoring and diagnostic center is not a real-time control system that responds and adjusts to system changes. Instead, it seeks to ensure longer-term performance of the system through more effective investment strategies. The business case for the center begins with identifying the high-value use cases for the center. These use cases are the “bedrock of integrated monitoring and diagnostic centers, backed by cross functional and technical expertise and include catastrophic failure avoidance, capital spending optimization, optimizing maintenance, analyzing and scoring risk, compliance productivity and dynamic asset rating.” (Groark 2019)

The business case for investing in the monitoring and diagnostic center that can support these use cases is made based on cost avoidance and revenue enhancements in several areas, including:

- Avoided catastrophic failure costs

- Avoided asset replacement costs

- Reduced routine maintenance

- Increased revenues from operational efficiency

- Reduced inventory value carrying costs

- Deferred asset replacement costs

Power Generation

In a 2017 article, Boston Consulting Group authors assert that the power generation industry is experiencing a sweeping transformation and that, over the next decade, unprofitable power plants will be “culled from the ranks of competitors by mergers and plant shutdowns.” (Stock 2017) It believes that producers must take a much broader approach to survive and create long-term value, going “far beyond traditional cost reduction and consolidation measures, to continually improving operational efficiency over the long term.” (Stock 2017)

Their solution is to apply the principles of lean management to power generation by transitioning “to an integrated, sustainable lean production system that covers all aspects of business requirements, operational improvements, people management, and performance governance,” starting by identifying its core business requirements and objectives and then applying lean tools to improve the high-priority areas of its operation.

The key to this integrated approach is to take full advantage of what the authors call “Industry 4.0 technologies,” including big data, advanced robotics, and additive manufacturing. “Power Generation 4.0 is a set of technology levers that provides the basis for achieving a step-change in efficiency across the power-generation value chain and for promoting improvements in health, safety, and environmental protection.” (Stock 2017) For example, implementing a new monitoring center that reports both system performance and the condition of the plant at the part level enabled one power producer to reduce the number of unplanned shutdowns by 50 percent in 5 years, saving approximately $3.55 million dollars per year. The pathway to making the business case for the benefits of Power Generation 4.0 begins with answering a number of questions:

- Have we thoroughly considered the full set of levers available for improving operational efficiency that is currently at our disposal?

- To what extent have our recently applied efficiency measures enabled continuous improvements rather than one-off cost savings? How effectively are we laying the foundation for sustained productivity growth?

- Are our employees ready, willing, and able to autonomously identify and appropriately address inefficiencies in their daily work?

- Have we agreed on a technology roadmap for the next 5–10 years that would generate efficiency gains across all areas from procurement to sales?

What These Examples Tell Us about Developing an Effective Business Case for TSMO

Key takeaways for effectively developing and using a business case:

- Tell a story using scenarios, in non-technical language, of everyday transportation situations that show the personal impacts of congestion, unreliability, etc., and how TSMO can help.

- Engage a wide range of stakeholders and decisionmakers so that they understand the potential value of TSMO investments to their organizations and to system users.

- Clearly define needs and opportunities where TSMO strategies can be viewed as potential solutions.

- Quantify the measurable or predictable cost of TSMO investments, including capital requirements and operating costs.

- Identify and quantify the benefits that accrue to each category of beneficiary: agencies, system users, and society at large.

- Use appropriate discounting methods to recognize the time phasing of costs and benefits