Role of Agency Culture in Mainstreaming TSMO2. Approaches to Organizational Improvement and Culture ChangeThis chapter presents well-known examples1 of organizational performance improvement techniques, including Lean Six Sigma, the Baldrige Performance Excellence Program, the Balanced Scorecard, and the Capability Maturity Model (CMM), that can help agencies make changes in their organization, including changes to culture. They enable an agency to understand what needs to be changed in its culture and track its changes to achieve the desired outcomes. The approaches discussed apply to changing an agency’s or organization’s culture regardless of field:

Each of the approaches highlighted in this chapter is different, but they all provide a structured framework to measure, understand, and change culture at every level. There is no right or wrong approach, but rather one should use the approach that would best fit with the goals of the agency and the inherent perspectives on measurement, systems integration, and structure. Any of these approaches is better than being purely reactive when it comes to the topic of culture change. Performance improvement techniques have a range of advantages that can be beneficial to an organization beyond just process controls and improved manufacturing, where many of these approaches were first developed. Fryer et al. (2007) found several benefits in their review of performance improvement approaches:

The research spanned across sectors and regions and found that, within the public sector, management commitment was universally cited as critical for any success. Next were customer management, process management, and employee empowerment, which were considered key in 75 percent of the cases. (Fryer et al. 2007) The public sector is prone to reorganizations and leadership changes, which impact continuing commitment to an approach for organizational improvement. Lean Six SigmaSix Sigma began in the mid-1980s at Motorola to improve engineering processes and eliminate variation. Lean is another process improvement and excellence approach that was developed from the Toyota Production System that sought to reduce waste, overburden, and inconsistency. (Antony et al. 2017b) Lean Six Sigma branched out by combining these approaches and expanding certifications to all professions/occupations. Lean Six Sigma is collaborative and aims to reduce the eight sources of waste in any profession or occupation. As noted by Summers (2011), the first letter of each source forms the acronym DOWNTIME:

Lean Six Sigma has been used as a framework for organizational culture change. (Summers 2011, Thomas et al. 2008) It could be applicable beyond the manufacturing industry to the more services-oriented public sector fields that may be most similar to transportation agencies. (Furterer 2016, Fryer et al. 2007, Antony et al. 2017a) Examples from the FieldThe government of Arizona has transformed how agency leadership and staff conduct their work using the Lean approach. In 2015, the incoming Governor of Arizona brought with him the Lean approach from his work in the private sector. He led the State in developing and implementing the Arizona Management System (AMS) through a focus on innovation and continuous improvement. As noted by the State of Arizona (2020), primary components of AMS are as follows:

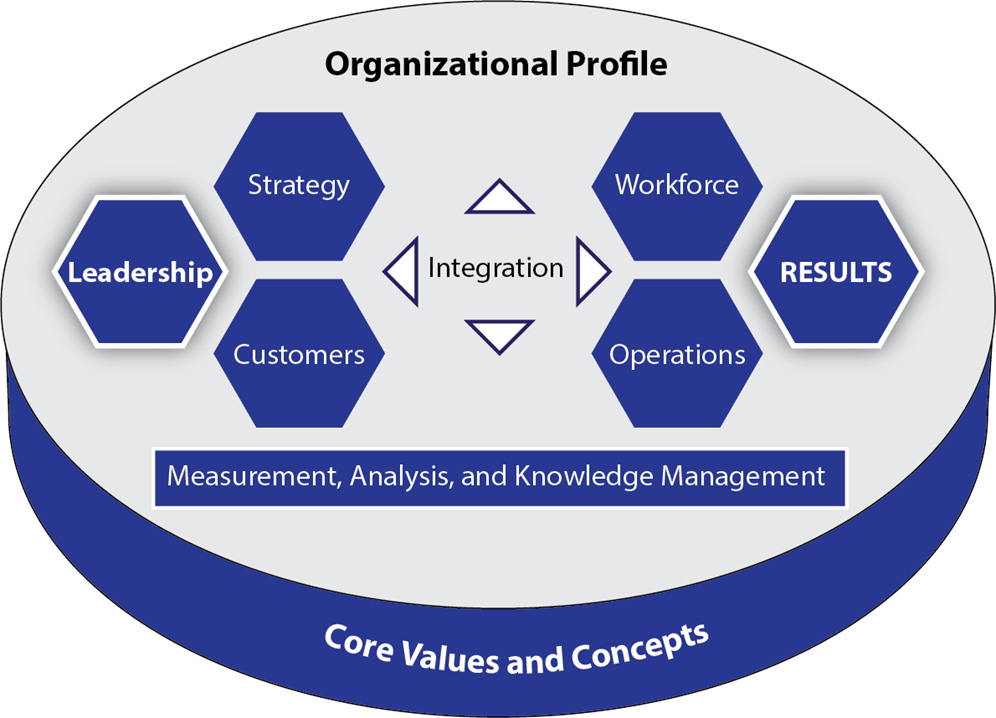

All State agencies within Arizona have adopted the system, including Arizona DOT and its TSMO Division. The TSMO Division was created around the same time as when the State adopted the AMS, which has permeated the work of the TSMO Division. According to the TSMO Division Director, the leadership and managers have been thoroughly trained in Lean management, and it has been engrained into their work. They work continually to have the Lean approach embraced by staff. Managers constantly use this system and encourage (or require) their staff to use it through huddle boards and tiered huddles to share and move issues up and down the management chain. The TSMO Division applies process mapping to remove waste in processes and structured problem-solving approaches and implements a “Plan – Do – Check – Act” approach to their functions. The TSMO Division Director reports that there have been significant positive impacts from using the AMS. For example, Arizona DOT significantly reduced wait times at the Department of Motor Vehicles by diving deep into its processes. The TSMO Division also won a national award for a restriping and signing project in the Phoenix area for a corridor that used to have vehicle crashes multiple times a day. The benefit-cost ratio of the project was very high, around 700 to 1. As part of the AMS, the TSMO Division has performance measures that feed up into the DOT cabinet level. Managers within the TSMO Division are responsible for reporting, up to the TSMO Director, three to four simple performance measures using green, yellow, and red color‑coding. Managers are encouraged to report red if there are problems and detail how they will address those issues. It is instilled into their culture, and managers are not penalized for revealing negative metrics. They focus on positive incentives, such as bonuses and weekly kudos reports, instead of penalties. They measure how well this is changing the culture of the DOT and TSMO Division using annual employee engagement surveys. The Lean approach has also been used in the Lean Everyday Ideas program as part of the Colorado DOT, wherein one person identifies a problem, comes up with an innovation, implements the plan, and then informs others so that it can be borrowed (see https://www.codot.gov/business/process-improvement). While the ideas span the range of DOT activities, they also apply to TSMO (e.g., collecting site data through applications, creating a folding icy bridge sign). Baldrige Performance Excellence ProgramThe Baldrige Performance Excellence Program represents a framework for high-performance management systems. (Evans and Jack 2003) It was originally developed by the National Institutes of Standards and Technology in the late 1980s as U.S. leaders realized that American companies needed to focus on quality to compete in a global marketplace. The goal of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Improvement Act of 19872 was to enhance the competitiveness of U.S. businesses, with its scope expanding from manufacturing to healthcare, educational, and non-profit/government organizations. (National Institute of Standards and Technology 2019) The Act created the Malcolm Baldridge National Quality Award, which was developed to identify role-model businesses, establish criteria for evaluating improvement efforts, and disseminate best practices. The award has brought recognition, resources, and improvement to a range of organizations over the years (from household names to largely unknown organizations—see https://www.nist.gov/baldrige/award-recipients). It is different from other approaches because it takes a systems approach to understand and change an organization. This is particularly relevant for the complex domains within which transportation agencies operate, and it reflects a key aspect of TSMO. The systems approach and framework are represented in figure 1. As noted in the figure 1, measurement, analysis, and knowledge management underpin the effective integration of strategy, workforce, operations, and customers to provide results.

Source: NIST 2019. Figure 1. Graphic. Baldrige Performance Excellence Program framework.

Organizational Profile is built on Core Values and Concepts. Organizational Profile includes Integration. On the left of Integration is Leadership, which includes strategy and customers, and on the right is Results, which includes workforce and operations. On the bottom is measurement, analysis, and knowledge management.

How Can Agencies Apply This to TSMO?A TSMO Division of a transportation agency could use the Baldrige framework, which entails a structure of internally facing questions and measures, to become more learning-oriented with a focus on improving results and creating value. The results and value related to TSMO may be measured in decreased average travel time, reduced incident clearance time, and increased travel-time reliability. Baldrige assessment questions ask individuals to mark whether they strongly agree to strongly disagree to statements such as: (https://www.nist.gov/baldrige/self-assessing)

Balanced ScorecardThe Balanced Scorecard is another approach to performance management that was originally conceived to manage intangible assets. (Kaplan and Norton 1992, Kaplan 2010) It is a semi‑structured report form that is used by managers to track various aspects of strategic execution activities, as well as monitor the impact of those activities. There are three critical aspects of the Balanced Scorecard: (1) focus on the strategy set forth by the organization, (2) select a small number of data items for monitoring, and (3) include a mixture of financial and non-financial data. (Kaplan 2010) As discussed in Kaplan and Norton (1992), the Balanced Scorecard focuses on four perspectives and related questions:

The Balanced Scorecard has been successfully implemented in a range of businesses; however, it should not be viewed as purely a set of performance measures. Instead, it should be incorporated into the management approach as a cornerstone of how things are done, both for ongoing performance and during the change process. (Kaplan and Norton 1993) How Can Agencies Apply This to TSMO?A transportation agency could use this approach to align strategy and performance measures, including measures related to human capital and customer satisfaction, as well as a non financially related measure of impact on the community (which are becoming more important to the evolution and operations of DOTs). Capability Maturity ModelAlthough the Capability Maturity Model is not considered a formal framework of culture change, it is derived from earlier work in the software development field, which did include a notion of changing process and performance improvement. It focuses on three tenets: (1) process matters, (2) prioritizing the right action is important, and (3) focus on the weakest link to improve performance overall. (FHWA 2016) For TSMO, the approach looks at process improvement in six capabilities (business, systems and technology, performance measurement, culture, organization and workforce, and collaboration) and across four levels (low to high). The approach was first applied to focus on overall TSMO improvement and has now been adapted for individual TSMO strategies, such as incident management, work zone management, and signal control as “capability maturity frameworks.” The TSMO Capability Maturity Model, used by many State DOTs to assess and advance their TSMO capabilities, describes the culture dimension as “technical understanding, leadership, outreach, and program authority.” (FHWA 2012) FHWA (2012) defines the four levels of the culture dimension as follows:

The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) provides a web-based tool that guides users through a customized self-evaluation based on the TSMO Capability Maturity Model. (AASHTO n.d.) It helps agencies identify their current levels of TSMO maturity and provides recommended actions to advance through the levels. For example, to move from level 1 to 2 on the culture dimension, the tool recommends “Developing a business case for TSM&O and continuous improvement of operations performance.” (AASHTO n.d.) The tool recommends “Establishing TSM&O with a formal core business program status equivalent to other major programs” to move from level 2 to 3. (AASHTO n.d.) The TSMO Capability Maturity Model is a tool that agencies can adapt to better gauge and guide the culture of mainstreaming TSMO within their organizations. 1 FHWA is not endorsing any particular approach or method, and this list is not exhaustive. [ Return to Note 1 ] 2 Pub. L. No. 100–107. [ Return to Note 2 ] |

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||