National Inventory of Specialty Lanes and Highways: Technical ReportChapter 1. Overview of Specialty Lanes and HighwaysTransportation agencies across the country have long grappled with the challenge of providing mobility options for travelers in high-demand, congested, or constrained travel corridors. Agencies at the Federal, State, metropolitan, and local levels have responded with a variety of techniques and approaches to improve traffic flow, enhance mobility, and provide travel options. The methods go beyond traditional roads and freeways and involve the implementation of specialty lanes and highways—facilities with unique operational rules or tolling (e.g., congestion pricing) that provide access for select user groups who meet the qualifications. These targeted user groups usually consist of carpools, vanpools, transit buses, alternatively fueled vehicles (e.g., biofuels, ethanol, solar, and electric), single-occupant vehicles, and trucks. The types of specialty lanes and highways can consist of managed lanes, toll roads, turnpikes, and facilities with active traffic and demand management (ATDM). Some of these special lanes receive oversight or permissions granted to facilities on the Federal highway system, and others are managed by States, counties, and private concessioners. This document’s only purpose is to compile a one-stop listing of ten types of specialty lanes that supplement our Nation’s general purpose highways, including even some privately-owned facilities not under Federal oversight, for the purpose of creating, in effect, a utility desk reference. The project team compiled and aggregated raw statistics of highways containing lanes that are not effectively general-purpose (GP) lanes. The main questions this report seeks to answer are:

Managed lanes are described and defined in FHWA’s “Managed Lanes: A Primer” (FHWA-HOP-05-031) as “highway facilities or a set of lanes where operational strategies are proactively implemented and managed in response to changing conditions.” For purposes of this document, specialty lanes or managed lanes are lanes that are not GP lanes on America’s highways, or informally, “everything else,” exclusive of ramps, auxiliary lanes, and common shoulders. Specialty lane characteristics include access control via price (e.g., tolls), vehicle eligibility (e.g., occupancy or permits), or time of day (e.g., peak-hour reversible lanes). The project team primarily considered free-flowing facilities on freeway corridors, and not arterials. For the purposes of providing the reader with a starting list of peer experts, we identify California, Washington, Virginia, Texas, Florida, Minnesota, and Georgia, as states that have placed significant focus on research and deployment of managed facilities, i.e., not inclusive of toll roads. Not coincidentally, these States have the most number of managed facilities. A few types of facilities were not included in this list, primarily because those roads were effectively static in their purpose and not proactively dynamic in managing traffic. Specifically, the following types of roads did not make the list:

Project Scope and ObjectivesThe objectives of this project were to research, compile, and aggregate a national clearinghouse inventory (lists) of specialty lanes and highways that are not merely general in purpose, and any known planned facilities, as of the target publish date of this document. The inventory is not intended to provide any subjective commentary or synopsis of the merits, challenges, controversies, or any other discourse on the effectiveness of specialty lanes and highways. This document aims to serve as a reference-only for transportation agencies and practitioners who work with specialty lanes. Need for an Inventory of Specialty Lanes and HighwaysThe last inventory by the FHWA occurred in 2007, as part of the FHWA HOV Pooled Fund Study, so an updated inventory is needed. This latest effort compiles more data elements and facility information to be useful to a wide array of audiences, including facility users, practitioners, and state and regional highway authorities. Structure of ReportThe report consists of four chapters followed by an appendix that details inventory information for each State.

Types of Managed Lane FacilitiesThe inventory divides the facilities based on their operational attributes, such as pricing, vehicle eligibility, and passenger occupancy eligibility permissions. Specialty Lanes Included in This ReportManaged Lanes. These lanes (or facilities) usually run adjacent to, or sometimes down the middle of, common highways. The facilities are auxiliary or supplemental to trunk GP lanes. A fundamental precept is that optional use is not prescribed. Examples of this group are high-occupancy vehicle (HOV), high-occupancy toll (HOT), express, part-time shoulder, and bus and truck-only lanes. These lanes run parallel to the GP lanes and often share a common right of way. Eligible vehicles can enter and exit the lanes based on desired destinations, vehicle qualifications, and willingness to pay a toll. Toll Roads or Turnpikes. The second group is also optional, in the sense that drivers choose to pay to use the facility. However, a different incentive and legacy exists for these toll roads which are inviting and convenient. For the most part, States fully own tolled turnpikes. Many are legacy roads that were funded and constructed without Federal-aid highway funds, although some may have been adopted into the Federal system afterward. For example, in 1957 the then-Bureau of Public Roads (forerunner to the Federal Highway Administration) incorporated 2,100 miles of toll roads in 15 States (fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/tollroad.cfm). Many toll roads were/are often built on their own rights of way leaving them “off” of the Federal system. Common examples of these are the Pennsylvania Turnpike, New Jersey Turnpike, Ohio Turnpike, Indiana Toll Road, Chicago Skyway, and much of the Florida Turnpike system. Table 2 indicates whether the facility type has tolling. The following sections describe the facilities in more detail.

Note: There may be singular exceptions to these general criteria. High-Occupancy Vehicle (HOV)An HOV lane or facility is one of the earliest and most common types of managed lane facilities; in fact, HOV lanes may be called the forerunners of all managed lanes. The first one was the Shirley Highway busway in Northern Virginia in 1969, which was later expanded to include carpools in 1973 (Chang, et al, 2008). HOV facilities provide access for carpools, vanpools, transit, and other eligible vehicles, such as, special-permit allowances like electric vehicles. The important distinction between HOV lanes and other specialty lanes is that vehicles are not assessed tolls to enter the specialty lanes from the general-purpose lanes. Two HOV lanes, however, do operate on toll roads: the Dulles Toll Road in Northern Virginia and the SR 520 Bridge in Washington State. For these two facilities, drivers pay a toll to enter the limited access corridor, but they do not pay an extra toll to enter the HOV lanes. For carpools, the eligibility conditions vary depending on the corridor. Some facilities allow vehicles for two or more occupants (HOV 2+). Other facilities require three or more occupants (HOV 3+). A large proportion of these facilities are single lanes and are situated parallel to the GP lanes. These lanes have separation from the GP lanes by a buffer or a permanent barrier and have access at the endpoints or intermediate access points along the corridor. Figure 1 shows an example of a sign for an HOV facility.

Source: Texas A&M Transportation Institute A freeway in Nashville, Tennessee with an overhead sign bridge. A sign on the bridge has the following text: 'HOV2+ Only, 2 or more persons per vehicle, 4 pm – 6 pm, Monday – Friday.'

High-Occupancy Toll (HOT)A high-occupancy toll (HOT) facility can be understood as an HOV “plus” facility; at its core, it is an HOV facility, but it also allows lesser-occupant vehicles (e.g., single-occupant vehicle or two-person carpools, depending on the eligibility) to use the facility by paying a toll. The first HOT lanes were developed in 1995 and 1996 in California, on SR-91 in Orange County, and on I-15 in San Diego, respectively. Many HOT facilities were built with federal congestion mitigation and air quality (CMAQ) funding, which mandates that the carpools continue to use the facility toll-free. However, some facilities, perhaps under differing legislation, may provide discounted toll rates to HOVs during peak periods. For carpools, the eligibility conditions vary by every HOT facility. Most facilities allow HOV 2+ or HOV 3+. Many agencies converted former HOV lanes into HOT lanes, usually to take advantage of any excess capacity, but as mentioned, they must abide by CMAQ tenets. Figure 2 shows an example of a HOT lane.

Source: Texas A&M Transportation Institute Overhead of a two-lane, bi-directional managed lane that operates in the median of I-25 in Denver, Colorado. The left lane has the word 'Toll' in white striping and the right lane has the letters 'HOV' in white striping. An overhead sign bridge is visible with the text 'Toll Lane Only' on the left and 'HOV2+ Only' on the right.

Express Toll Lane (ETL)An express toll lane (ETL) is a specialty lane that regulates access using all-electronic tolling. Generally speaking, all vehicles receive a toll charge as they enter the facility and/or pass toll gantries; the amount of toll is tied to the length of the trip. These facilities are not mandated to exempt HOVs from paying a toll, but a small portion of them may allow HOV discounts or may allow registered vanpools and transit vehicles to travel toll-free, as an incentive or reward to those community programs. Figure 3 shows an example of an entry point to an ETL. Figure 4 shows an example of a buffer-separated ETL and GP lanes.

Source: Texas A&M Transportation Institute

Source: Orange County Transportation Authority Non-toll Express Lane (NTEL)A non-toll express lane (NTEL) is a specialty lane that provides a long distance bypass without charging a toll. The distinction here is that there are no tolls, but drivers might choose this lane as a means of bypassing clogged local exits; i.e., a non-tolled fast lane as it were. Generally, these facilities provide some type of physical separation, whether through the use of a striped buffer, barrier, or physical separation from the GP lanes. An example is the I-80 Express lane in New Jersey. It provides an NTEL that limits access to only a select few exits. Travelers who want to use midpoint exits have to leave the express lanes and use the local lanes to access mid-point exits. In summary, such facilities allow drivers to bypass local traffic. The benefit in time is gained by avoiding the congestion created by the weaving and confluence of locally travelling vehicles. Toll RoadA toll road may also be known as a turnpike, or commonly, a “for pay” highway. The distinction here is that, generally speaking, these roads do not parallel a general-purpose highway as an HOV or HOT lane would, which is to say, they do not offer a motorist a managed lane option-trip of a same-numbered adjacent highway. Many toll roads/turnpikes were built prior to the establishment of the Federal highway system and they are operated by states or turnpike commissions; for example, the Pennsylvania Turnpike is operated by the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission. Toll roads have different types of payment mechanisms:

For tolled bridge facilities, drivers are required to pay a toll at the entry of the facility. This report includes both toll roads and toll bridges in the toll category. Figure 5 shows an example of a tollbooth facility. A toll booth. On top of the toll booth structure is a set of three signs over a set of lanes. The text on the three signs read as: (1) Exact Change, Cars Only, No Trailers, (2) Full Service, and (3) EZ Tag Only, Narrow Lane, Cars Only.

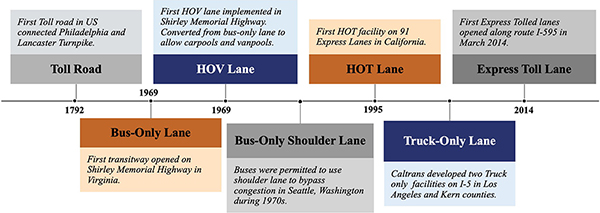

Private agencies and companies also own and operate tolled facilities in the United States, beyond the number of State departments of transportation and other governmental entities. Truck-Only Lane (TL)A truck-only lane (TL) herein is a truck-only dedicated facility, and not merely a truck “passing” lane or slow(er) lane on a regular highway, nor is it a climbing lane or a downgrade lane positioned on a steep grade. A truck-only facility intends to separate heavy freight-carrying trucks from passenger vehicles on level-graded facilities, reducing safety conflicts by eliminating mixed flow operation between those vehicle classes. Presently, California has the only five known operational truck-only lane facilities in the U.S.; two I-5 truck-only lanes in Los Angeles County, the I-15 truck-only lanes in San Bernardino County, the SR-60 truck-only lane in Riverside County, and the I-5 truck-only lanes in Kern County. As a point of reference, after constructing the new I-5 alignment in L.A. County over 30 years ago, the original alignment was kept for the truck-only lanes. Green guide signs encourage passenger vehicles to continue travelling in the main travel lanes and to not use the truck-only lanes. However, since green guide signs are not enforceable, passenger cars are not entirely prohibited from using the truck-only lanes. All facilities are owned and operated by the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans). At the time of this report, the Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) is planning a truck-only facility with an expected construction start date of 2025. The “I-75 Commercial Lanes” is proposed to be a 38-mile facility that will run northbound-only in parallel to the existing I-75 highway from approximately Macon to McDonough, near the southeast portion of the Atlanta metropolitan region. The purpose of the facility is to separate the heavy vehicle freight traffic to Atlanta that generally originates from the Georgia ports of Brunswick and Savannah. The facility will have a few local exits, but GDOT anticipates a very high percentage of freight traffic will make the entire 38-mile trip. The Georgia I-75 Commercial Lanes are not included in the National Inventory, because only operational facilities are listed in these data. Bus-Only Lane, Busway, or Transitway (BL)A bus-only lane (BL), busway, or transitway is dedicated for use by buses and transit vehicles only. This facility is designed to improve bus speeds and travel time reliability in congested areas. Many cities have bus-only lanes on arterials, but the inventory only lists facilities that are present on freeway and limited-access corridors. For example, New Jersey has an exclusive BL facility along I-495, connecting the New Jersey Turnpike to the Lincoln Tunnel. Bus-on-Shoulder (BOS)A bus-on-shoulder (BOS) facility permits buses to use the shoulders to avoid congestion along the roadway. Generally, buses may use the shoulder lane only when the mainline traffic speed goes below a specific threshold. This facility type promotes transit ridership by increasing reliability for bus routes in congested corridors. Shoulders are improved to handle the conditions and signage displays the rules. As an example of how BOS operates, in Minnesota, congestion (defined by speeds) must pre-exist, so almost by rote, BOS occurs during recurring congestion periods. The maximum speed of the buses on the shoulder is 35 mph and buses are not allowed to exceed traffic by more than 15 mph, except for special circumstances. Buses may “dead-head” (operate empty) and must yield to vehicles exiting and entering at interchanges. Motorists have a duty to obey some rules too, and can be ticketed, but the professional bus drivers are deemed to have the best advantage to avoid conflicts and accidents. The decades-long existence of BOS in Europe and in 12 U.S. States attests to their efficacy. Figure 6 presents an example of a BOS lane. Dynamic Part-Time Shoulder Use (D-PTSU)Dynamic part-time shoulder use (D-PTSU) allows vehicles to temporarily use the shoulder lanes, as indicated by highway operators. The opening of the part-time shoulder usually occurs when the mainlines (or general purpose, i.e., GP lanes) experience traffic congestion and an operator in a traffic management center opens the shoulder for use. Typically, dynamic signs at the entry of the shoulder display open/closed status for informing users when the lanes are open. Static Part-Time Shoulder Use (S-PTSU)Static part-time shoulder use (S-PTSU) allows vehicles to use shoulder lanes during a pre-established schedule. Generally, a S-PTSU facility opens during typical recurrent weekday morning and afternoon peak periods, usually when traffic congestion is present on the adjoining lanes. History of Specialty LanesThe rate of vehicular growth has been increasing, but the highway infrastructure to serve the desired capacity has not kept pace with traffic growth. Different operational and management strategies have been tried to accommodate peak-hour traffic. Outside of toll roads (e.g., early cross-state wagon-and carriage trails, and later, state-financed turnpikes) the introduction of the concept of managed lanes began in the 1970s as a means to increase freeway efficiency. Figure 7 shows the introduction of various managed lane facilities over time, and the following sections describe them in more detail.

Source: Texas A&M Transportation Institute A timeline that shows the progression of key milestone during the history of managed lane development. A set of seven rectangles describe the key events along the timeline. From the left to the right, the text in the individual rectangles reads as: (1) Toll Road, First Toll Road in US Connected Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, 1792; (2) Bus-Only Lane, First Transitway opened on Shirley Highway in Virginia, 1969; (3) HOV Lane, First HOV lane implemented on Shirley Memorial Highway. Converted from bus-only lane to allow carpools and vanpools, 1969; (4) Bus-Only Shoulder Lane, Buses were permitted to use the shoulder lane to bypass congestion in Seattle, Washington during the 1970s, (5) HOT Lane, First HOT facility on 91 Express Lanes in California, 1995; (6) Truck-Only Lane, Caltrans developed two truck-only facilities on I-5 in Los Angeles and Kern Counties; (7) Express Toll Lane, First Express Tolled Lanes opened along route I-595 in March 2014.

Toll RoadHistorically, toll road facilities were an early form of specialty roadway facilities. A toll road is a publicly or privately managed facility that collects tolls from users. Tolls can either be collected manually at toll booths or electronically using a transponder; it depends on the evolution of each particular facility. The first engineered and compacted road in the United States was built in 1795 and was designed for horse-drawn wagons. The “Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike” in Pennsylvania had ten “toll houses” thereby concurrently denoting it as the first toll road. Over time, many states and/or private developers built their own toll roads or turnpikes. Some of these agencies were eventually absorbed by the states; others continue today as any number of turnpike commissions, state tolling authorities, quasi-governmental agencies, or interstate compacts. (Source: U.S. DOT/FHWA, search: “Highway History.) Bus-Only LaneThe first application of managed lanes consisted of a bus-only lane outside of Washington, DC, in Northern Virginia; the Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway in 1969 (Chang et al., 2008). The ridership on the buses increased steadily, but the bus capacity remained underutilized. In December 1973, transportation planners opened the lanes to carpools and vanpools (Turnbull, 1990). High-Occupancy Vehicle LaneDuring the 1970s, HOV facilities became a significant alternative to fulfill the peak demand needs and were increasingly considered by planners in highway improvement projects. Turnbull (1990) performed an overall assessment of six HOV facilities and found various factors that led to the development of HOV projects. The study categorized the HOV projects based on features such as planning, decision making, and institutional arrangements, and examined the reasons behind the development of these projects. In another study, Dahlgren (1994) studied the benefits of adding an HOV lane instead of a GP lane. His study assumed that car users select HOV lanes only when there is a time differential between an HOV and GP lane. The study found the addition of the HOV lane to be efficient if the proportion of HOVs reached 20 percent. Part-Time Shoulder Use LaneDuring peak traffic periods, existing road infrastructure may be unable to serve the excess demand. The FHWA, in coordination with State and local departments of transportation (DOTs), works to maximize the efficiency of existing infrastructure through various strategies. Transportation systems management and operations (TSMO) plans strategize ways to restore and maintain the existing transportation system during peak demand. Part-time shoulder use (PTSU) is one of the TSMO strategies that involve the temporary use of shoulder lanes during certain hours of the day. It is one form of active traffic management and a very cost-effective solution to congestion problems. State DOTs and various local agencies have implemented part-time shoulder use to address peak demand and improve transportation performance. This strategy is modified based on requirements such as the location of the shoulder (left or right), vehicle use (bus or HOV), and schedule (FHWA 15-23, 2016). Except for temporary use during peak time, these shoulder lanes, of course, serve as refuge/emergency purposes. A great deal of concern initially arose over the efficacy of using “breakdown” lanes for active traffic. In the right context, PTSU facilities can be operated safely (FHWA 15-23, 2016). One example of a recently opened PTSU facility is the I-670 ‘SmartLane’ in the Columbus, Ohio metropolitan region that started operating in October 2019. During the first couple of months of operation, the Ohio Department of Transportation observed a significant reduction in mainline crashes that were previously the result of stop and go traffic. High-Occupancy Toll LaneFielding and Klein (1993) first introduced the concept of HOT lanes. In this type of priced lane, typically single occupant vehicles (SOVs) that do not meet HOV2+ or greater requirements pay a toll, and higher-occupancy vehicles (usually either two or more occupants or three or more occupants) remain exempted from paying the toll. These lanes can use underutilized HOV lane capacity and may also serve as a revenue source for meeting other regional transport needs (Varaiya, 2007). HOT lane facilities are signed as “Express” lanes per mandate by the Manual of Uniform Control Devices (MUTCD 2G.16.05). There can be confusion, as many highway engineers and the public use the coloquial “expresslanes” as a wide, catch-all term, but technically “Express Lanes,” for example, are not HOT lanes. The first HOT lane facility opened as the “91 Express Lanes” (thus, perhaps, establishing the signing precedent) in California in 1995. This facility has two primary lanes in each direction and is separated from the main lines with plastic lane markers. As noted above, the functionality of “Express Lanes” is different from that of HOT lanes. Thus, the reader is cautioned not to confuse the purpose with the vernacular. HOT lane facilities follow open road tolling to reduce time delay. In this system, users are charged a toll by the electronic toll system. In practice, each vehicle installs a toll tag, which is read by the overhead antenna, and the system deducts the toll amount from the user’s account. Users who do not have a tag can pay the toll via mail within a specified time period. Most of the HOT facilities have static or fixed toll rates throughout the day. A few HOT lanes, such as the I-66 Express Lanes in Virginia, have dynamic rates where toll rates change based on the time of day and traffic flow through the section. Usually, during morning and evening peak periods, toll rates increase with a rise in road traffic users, and rates are set according to a dynamic pricing formula. Express Lane“Express Lanes” are intended to provide a more reliable trip than congested general-purpose lanes. This type of facility targets, and benefits, longer trips. They have fewer entry and exit points as a means to bypass the confluence of local traffic lanes. Users can access or exit the facility at predetermined locations only. Express lane facilities can be tolled or non-tolled lanes, described as ETL and NTEL, respectively. In ETL facilities, all users pay the toll, and no exemption is given to any user, excepting perhaps reduced tolls as incentives to HOVs, for example. The 595 Express Lanes in Florida is a good example of an ETL facility. These lanes are parallel to the GP lanes and are generally located on the leftmost section in each direction. The GP lanes are separated by a concrete barrier to allow vehicles to move quickly and safely on the express lanes. The 595 ETLs offer a commuter incentive program by pre-registration, which rewards local HOVs with reduced tolls. Occasional HOVs pay the full toll. The Bergen-Passaic Expressway, is an example of an NTEL facility; it was constructed to alleviate (remove, via bypass of local exits) congested traffic on NJ 4 (State Road in New Jersey). Why Do We Need These Specialty Lanes beyond the Public Streets and Highways?A common argument from road users is, “I already pay taxes; I shouldn’t have to pay more to build or use these roads.” It’s true that many of these specialty roads have a public financing element, but some are funded in partnership with private-sector companies that seek a return on investment. Another part of the answer exists in local, State, and Federal governments’ endorsement and promotion of transit, commuter, and parking benefits that come from these specialty lanes. Other answers may lie in that any benefit accorded to qualified vehicles to use these managed lanes indirectly benefits the public by better managing use of all public facilities through sharing and/or providing options to the same goal, namely getting more people to more places and in less time than might otherwise exist absent these managed systems. A key point is that any facility that purports to provide a more reliable trip (i.e., faster) than adjacent congested highways, needs to achieve that objective, or travelers would use alternate routes; therefore, it is in the operator’s interest to meet that objective. Some of the earliest managed lanes were bus-only lanes and commuter carpool lanes devised to provide a more reliable trip for those users. The first freeway specialty lane in the United States was the Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway in Northern Virginia, between Washington, DC, and the Capital Beltway, and was opened in 1969 as a bus-only lane. In December 1973, because excess capacity was evident, it was opened to four-person carpools to promote carpooling into Washington, DC. Over time, many more iterations of special use lanes or facilities came to be around the country, all of which had some variation of theme on how to provide an improved trip reliability or safety segregation that would benefit the motoring public. In summary, some of those reasons are:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||