| Skip to Content |

|

Bridging the Communications Gap in Understanding Road Usage ChargesChapter 5. Communication MediaStates used a variety of different communication media to interact with the public, participants, and other target audiences. Several of these media can take multiple forms. For example, depending on the intended audience, in-person contact can include focus groups, town hall meetings, or one-on one contact with elected officials. Table 3 shows which State pilots used the different communications media. The letter "Y" indicates yes, to the question and the letter "N" indicates, no. Figure 2 graphs the different communications media showing by frequency of use by each State pilot.

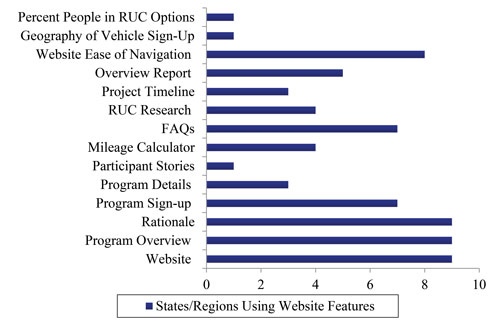

Figure 2. Chart. Total number of State pilots using each communication medium. Web PageThe majority of the State pilots chose to develop a Web page uses as the primary source for disseminating information. Of the 11 State pilots, 9 have Web pages. Web pages ranged from relatively simple to more sophisticated. However, most pilot sponsors appear to strive for a balance between providing enough information about road usage charges (RUC), pilot rationale, program sign-up, and frequently asked questions (FAQ) and providing too much information which might confuse the public (table 4 and figure 3). Oregon DOT provided the best explanation of the role of a Web page. According to the DOT, the Web page, "was the front door for the public, providing information that is most relevant to the public and potential users." Some States used the Web page to provide reference information to the public. For example, Colorado included all the pilot material from their first phase on the Web page. Other States used the Web page to promote other communications and outreach methods. For example, Hawaii posted notices of town halls on the Web page. Table 4 shows which States used each Web pages feature. The letter "Y" indicates yes, to the question and the red letter "N" indicates, no. Figure 3 shows how frequently each Web page feature was used by the State pilots.

1 Oregon is the only State with an operating program. [Return to note 1]

Figure 3. Chart. Number of Surface Transportation System Funding Alternatives funded pilot States using each of the 13 Web page features. Web Page Features Used by Surface Transportation System Funding Alternative Grant Pilot States/RegionsFrom the State with the most experience with RUCs, Myorego, Oregon DOT's Web page, is an example of a comprehensive Web page. The page explains RUCs work and why a new funding mechanism is needed. The learn tab has seven sub-sections that include information on the program (per mile charge, mileage reporting options and program size), another link to enroll in the program, the six-step sign up and monitoring details, stories of pilot participants explaining the value of RUCs, a calculator that compares how much a driver would pay in gas tax compared to RUCs, program FAQs, and research Oregon has conducted on RUCs. The connect tab includes a DOT blog, an email list-serve to find more information about the program, and customer service links for Oregon DOT as well as private technology providers. The press room tab has videos, news releases and media information about the program. The Web page also has a search feature. Washington State has a similar website with the homepage focusing on justification of the pilot and explanation of RUCs on its Web page. Other States developed less extensive Web pages. Currently, Hawaii's Web page has a program overview, a rationale for the RUC pilot, an RUC calculator, FAQs, and a project timeline. As it expands and develops its program, Hawaii may include additional information including program details, participant interest responses, and additional research. Two States currently do not use Web pages. For them, as they are developing their RUC pilots and focusing on legislative approval, a public Web page was perceived as a distraction which could provide misleading or out of date information to the public. Social MediaStates identified problems with relying on social media to communicate with stakeholders. California and Colorado, who had large social media presences, indicated that users responding to DOT social media threads were strongly opposed to RUCs. The pilot managers did not think this was representative of broader public opinion. Project participants largely support RUCs while the public has a mixed opinion of the concept. For example, one Facebook Live presentation generated a wave of red angry face emojis. Paid AdvertisingMost States did little or no general paid advertising. Washington, however, had a comprehensive advertising campaign that included messages on radio, newspapers, social media, and State Web platforms. Generally, print advertisements were limited to 100 words or less and radio commercials were limited to 15-30 seconds. Advertisements provided an overview of RUCs and a phone number, email, or link to members of the public wanting more information. News MediaMany States performed targeted outreach to the media. State DOT would share key facts with newspaper, TV, and radio reporters such as the amount most people pay for transportation annually, the difference paid between the gas tax and an RUC, privacy concerns, and program details. Most DOT expressed a willingness to define the narrative instead of having those opposed to RUCs define the narrative first. Many increased their news media outreach due to social media coverage or inaccurate news coverage of the pilots. Utah DOT opened its weekly internal meetings to members of the press to increase knowledge of RUCs. Personal ContactStates discovered that personal contact was a valuable medium for answering questions and providing detailed data. Like with communications outreach, there were five in-person contact methods used:

Lessons LearnedGenerally, States with more comprehensive communications and outreach campaigns with multiple communication media have had more ways to reach public audiences. Web pages are well suited to comprehensive strategies and are the most popular. Further, Web pages with more of the features and personalized content had higher participant support. Detailed information seems to be accepted when the pilot program features are limited and targeted (see appendix B). Various communication techniques that take advantage of personal interactions with the target audiences were perceived as most effective by the pilot sponsors. These include one-on-ones with elected officials and providing talking points to spokespeople. At least six States reached out to the news media and formed an advisory group. Both were important in educating the public about the program and framing the relevant questions. Being proactive in these communications messages increased success of the pilot programs. Advertising, focus groups, and town halls also were successful. Due to limited resources, many States did not take advantage of these options. But each plays a crucial role. Focus groups allowed DOTs to target messages to certain audiences and to understand concerns of those audiences. Town halls provided an in-person communication option that many elderly and rural residents valued. Communication that relied on social media was generally perceived by pilot sponsors as unsuccessful. This may have been because the responses received through this medium were negative and believed to represent a small fraction of public opinion. Further, responding to negative comments required significant time resources. None of the States who communicated via social media suggested that they would do so again. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||