Bridging the Communications Gap in Understanding Road Usage Charges

Chapter 4. Message Content

In studying the messages that comprise the most prevalent portion of communication activities, there was commonality across the topics that were addressed. This indicates that messaging components among States share many similarities. These commonalities have been distilled in the following short list (table 2):

- Message Component 1: Why are we conducting this pilot?

- Message Component 2: How does the pilot align with the long-term funding strategy?

- Message Component 3: Currently, how do we pay for transportation and how much do we pay? Would we pay more if road usage charges (RUC) were implemented?

- Message Component 4: How does the pilot maintain privacy?

- Message Component 5: How does the pilot mechanism protect security?

- Message Component 6: Explain the transition from gas taxes to this mechanism.

- Message Component 7: What are the costs of using this mechanism as opposed to fuel excise taxes?

- Message Component 8: Would rural residents pay more?

- Message Component 9: Are other State/Federal Governments conducting pilots?

- Message Component 10: Do pilots offer choices, and are they mandatory?

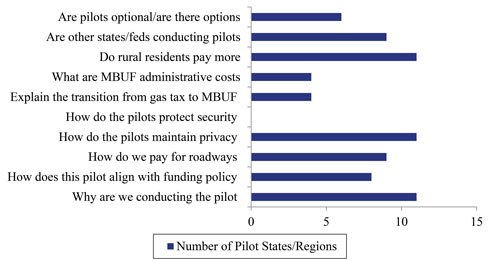

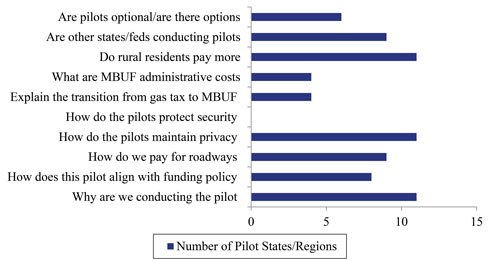

These questions and whether they were addressed by individual States in their pilots are shown in table 2 . The letter "Y" indicates yes, to the question and the letter "N" indicates no. Figure 1 shows how many States addressed each question.

Table 2. Ten common questions about road usage charges and whether they were addressed in Surface Transportation System Funding Alternatives funded State pilots.

| Messaging Component |

CA |

CO |

HA |

I-95 |

MN |

MO |

NH |

OR |

UT |

WA |

RUC West |

| 1. Why are we Conducting the Pilot? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 2. How Does the Pilot Align with Long-term Strategy? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 3. How Do We Pay for Transportation; Would We Pay More under RUC? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 4. How Does the Pilot Maintain Privacy? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 5. How Does the Pilot Protect Security? |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

| 6. Explain the Transition to This Mechanism? |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

| 7. What are the Costs of Using this Mechanism? |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

| 8. Would Rural Residents Pay More? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 9. Other States are also Conducting Pilots? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 10. Do the Pilots Offer Technology Choices? |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Figure 1. Chart. Number of State pilots addressing each of the ten road usage charge questions as part of their communications message.

(Source: Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).)

(Note: Number of States that Used/Adopted Message Components in Pilots are counted based on the number of States that adopted each message component. Each State is classified on whether they adopted the message component, not the degree to which they used the message component.)

Message Components Addressed in Pilots

The study concluded that message content of State pilot communications plans generally fell into one of ten components:

- Transportation Funding Challenges—Some States explained the long-term problem with the gas tax, the primary transportation funding mechanism, and provided limited information on other funding methods. Both California's and Oregon's Web page detail how the growth in the number of hybrid/electric vehicles and the failure of the gas tax to be linked to inflation are creating a significant gap in transportation revenue. States with more focused programs, such as Utah, reflect the change in their law that has recognized that electric vehicles do not contribute to infrastructure through a fuel tax. Several States detail the rationale for their pilot by explaining that an RUC is a potential solution that needs real-world testing. Others present an RUC as one of a range of solutions that is being explored. Oregon details several different RUC alternatives and suggests the importance of offering choice to different groups.

- Pilot Purpose—States participating in the Surface Transportation System Funding Alternatives (STSFA) program presented RUCs as a different way to finance the maintenance and/or construction of highways or transportation infrastructure. They emphasize that if the pilot is successful, RUCs may become a permanent option. Some States present RUCs as an alternative to the gas tax while others present it as an option to supplement it. Most States explain how over time RUCs could replace the gas tax. New Hampshire and Utah present pilots targeted to certain vehicle types as the first step in that process. Other States—such as Oregon (the only State operating a permanent RUC program)—detail how an increase in the number of RUC participants will allow a transition. Washington presents RUCs as a replacement for gas taxes, but at a level that produces slightly more revenue. For States that see RUCs as a substitute, such fees are couched as an option for those who pay the gas tax or a method to charge road users who are not paying their fair share (electric vehicle owners) to contribute. The I-95 Corridor Coalition presents the pilot as a simulation meant to educate consumers about alternative funding mechanisms designed to fund transportation.

- Transportation Funding Basics—Surveys have shown that American's have limited knowledge of what they pay to finance maintenance and construction of transportation infrastructure. While the average American pays approximately $22 per month in transportation taxes and fees, in surveys, many Americans believe they pay $100 or more (Agrawal and Nixon 2019). In studies, less than half of Americans knew that the gas tax was the primary roadway revenue source. Many respondents believed sales or property taxes are the main revenue source (Agrawal and Nixon 2019). State pilots concluded that because many Americans do not know that gas taxes fund transportation, they do not realize that improvements in fuel efficiency standards and the amount taxed not being indexed based on the rate of inflation has led to a decrease in revenue generated to fund highway projects.

Oregon explained that application of an RUC represents a continuation of the users-pay/users-benefit rationale that underlies the gas tax. Other States did not explicitly mention the users-pay rationale. Many States went beyond the cost of transportation programs to present—in Web pages, public meetings, and town hall meetings—the importance of well-performing systems on their Web page. The I-95 Corridor Coalition included this information on its Web page with detailed information on what each American pays and how much it costs to build and maintain roadways at a state of good repair.

- Privacy—States described how their pilot attempted to address privacy concerns. States who used a vehicle registry approach detailed how the registry approach could protect privacy. States with location-enabled global positioning system (GPS) options explained how it is technically designed so that program operators do not have access to the data collected. Some States stressed the anonymization of the data in which all personal information is protected and program administrators do not have access to sensitive information such as social security numbers or birthdates. States with private account managers explained that the private company collects the data and anonymizes it, not the public sector. Oregon explained that pilot participants who elect location-enabled services must choose a commercial account manager rather than a State account manager.

- Security—Some States discovered, as they conducted their pilots, that security was perceived as an issue. Given the security vulnerabilities in online systems and the sensitivity around personal data, States may wish to devote more time and resources, potentially in future pilots, to addressing security vulnerabilities.

Communications Program: Minnesota

Minnesota's current RUC program is focused on collecting RUCs on shared mobility fleets. The Web page is the main communication medium. The State has not engaged in any social media or advertising. There is no formal steering committee, but an informal group of Minnesota Department of Transportation (DOT) officials has circulated information within the department on the shared vehicle pilot. Minnesota DOT has made extensive use of a focus group with stakeholders, legislators, policy leaders and interest groups to explain the program and receive feedback. A technical advisory committee will be formed from focus group members. There have been no town halls or media outreach, however, legislators have been involved with the focus group and have briefed their colleagues on the program.

- Transition from Current Revenue Mechanism to RUC—Public interest in the transition from existing revenue mechanisms to RUC system varied by State. Oregon participants were unaware how the fuel tax is used and have not considered the need to transition to an alternative revenue mechanism. However, up to 1/3 of the Hawaii residents surveyed were concerned about a potential transition, indicating that they wanted a gradual approach. Hawaii used nuanced messaging that the project is only a simulation of replacement of the gas tax and that any true replacement will take 10-15 years.

- Administrative Costs—All of the State pilots recognized that most of the public is unaware of administrative costs related to collected gas taxes. Some States, however, found administrative costs were an important communication issue. Oregon participants were unaware of how much it costs to collect the gas tax and other revenue mechanisms and the State chose not to highlight this issue in the pilot. In Hawaii, implementation costs were discussed in 2/3 of town hall meetings. Hawaii residents were aware of the low gas tax collection costs. Hawaii DOT explained that collection costs in the test would be higher due to the limited sample size and current technologies. There was some thought that administrative costs of a statewide permanent program using smartphones as the technology would be cheaper.

- Rural/Urban Costs—Many of the pilots found the issue of rural versus urban fairness to be important. One of the public's major concerns about an RUC is that they are unfair to rural drivers (Atkinson 2019). Some rural residents mistakenly believed that because they drive further, they would pay more RUCs. However, results from pilots in a number of States have determined that this belief is unsubstantiated. One Oregon study showed that rural drivers would pay less in RUCs than gas taxes because the rural vehicle fleet is less fuel efficient. There are fewer electric and hybrid vehicles and a greater number of older vehicles. Oregon cited the study and used the anecdote that one rural Oregonian said, "so eastern Oregon motorists no longer need to support Portland electric vehicle (EV) drivers." Utah tasked its rural focus group members, such as the American Farm Bureau, with explaining why it would provide a savings to rural drivers. California found that sharing fact sheets showing how much each driver would pay was an effective educational tool. The I-95 Corridor Coalition included a calculator to compare how much rural drivers would pay with a gas tax compared to an RUC.

- Other State's Pilots—Lessons learned from early RUC deployments have contributed to successful pilots by new State participants because they are avoiding mistakes made by early implementers. Missouri, New Hampshire, and Utah all reference Oregon's pilot technical success including feasibility for its offset of RUC payments against gas tax charges with refunds at the pump. California included details of the Oregon and Washington pilots on its Web page and its legislator outreach. The I-95 Corridor Coalition used supportive statements from public officials and American Automobile Association (AAA) members in phases 1 and 2 of the pilots to build support for RUCs in other coalition States.

Communications Program: Delaware (I-95 Corridor Coalition)

The I-95 Corridor Coalition (the Coalition) had a multi-faceted pilot. As a Coalition representing 16 States and a wider geography, the message content was more general.

The Coalition identified the challenge with increased fuel efficiency and electric vehicles but also framed the pilot, "To ensure the voices of citizens along the I-95 corridor are heard because the Northeast is comprised of many small States with people and goods frequently traversing across versus the longer distances and bigger States in the West. The coalition did not address the long-term approach to communications.

The group showed how the gas tax is the primary funding method for transportation and how its purchasing power has declined due to inflation, the impact of improved fuel efficiency across the fleet and the increasing number of vehicles using no fuel. The coalition built on lessons learned from previous pilots including the need to provide a choice of mileage reporting and enabling drivers to opt out of data sharing. The coalition work also focused on the potential desirability of "value added services" that may result in an increased public acceptance of mileage-based user fees (MBUF). The coalition discussed the current low collection costs of fuel taxes but argued economies of scale will decrease MBUF costs. Given the diverse nature of Eastern States, future Coalition work will dive into rural versus urban perceptions of MBUF (e.g., Maine is the most rural State in the U.S. while other State members of the Coalition have some of the Nation's densely populated metropolitan areas). The Coalition did highlight work that other States were doing with links to California's program, RUC West, and impressions of individual States (Delaware, Pennsylvania) in the pilot. The coalition also focused on the voluntary nature of the pilots.

- Choice—Multiple States emphasized choices in their pilots. States that offered multiple RUC options detailed those options on Web pages, to legislators, and in polling. Oregon detailed the three different collection mechanisms (pre-pay into wallet with out-of-State mileage credited and value-added services; post-pay quarterly with out-of-State mileage credited and value-added services; and post-pay without out-of-State mileage credited and value-added services.) Many participants in States where non-GPS options were offered were unaware of non-GPS options. Utah explained that residents could pay the electric vehicle fee or an RUC and highlighted that the RUC option would be cheaper for those who drive less than 8,000 miles. All States explained to participants that the pilots were voluntary and that participation was not required.

Lessons Learned Based on Interviews with Surface Transportation System Funding Alternatives Pilot Partner States

For pilot rationale, States with comprehensive programs that explained the revenue challenges with the gas tax (electric vehicles, hybrids, declining purchasing power due to inflation) had higher levels of overall support than States that presented RUCs as supplemental revenue. States with more limited programs such as Utah benefited from a simpler message—that RUCs are an effective way to charge electric vehicle drivers for road usage (see appendix B).

For RUC as a policy change, States with a revenue-neutral approach or no formal communication on increased revenue fared better than States that describe RUC as new revenue. All pilots represent RUC as a potential alternative and something that needs to be studied. Pilot participants were sympathetic to these arguments. However, the pilots have a self-selection bias. While there were exceptions, participants opposed to RUC tended not to enroll.

For educating the public about revenue options, States that provided more detailed information about the amount drivers pay in revenue, such as California and Oregon, had better public acceptance than States who provided less detailed information. As discussed above, most Americans have no idea how much they pay for revenue, with the majority overestimating payment.

For privacy, security, transition, and administrative costs, States that detailed their privacy protections and explained the anonymized data collection process with the limited information collected on drivers had higher levels of user satisfaction and support. For security, no State had a systematic approach. Security measures were outlined in multiple pilots and States are working to add detailed encryption metrics. For transition, States that explained the details of the transition, including timeline and costs, fared the best. States that detailed how RUC collection costs were high today but would likely decrease over time with improved technology and economies of scale had the highest stakeholder support.

Among the equity and fairness issues of RUCs, the one of greatest interest among pilots was the misconception that rural drivers would pay more in RUC fees. Pilot results determined that on average rural vehicles would pay less under an RUC system than under a gas tax system. This is not to say that other equity issues, like income, may not be important for the future. States that highlighted how variable pricing would result in urban areas paying more, received higher levels of rural support. However, many States were hesitant to mention variable-pricing because it might reduce public support for RUCs.

States (Oregon and Hawaii) that mentioned the possibility of a Federal RUC pilot, multi-State partnerships (including RUC West and the I-95 Corridor Coalition) and the need for a State or Federal clearinghouse to process out-of-State RUC transactions had the highest stakeholder support. States that offered and promoted multiple RUC options, as well as those that noted program participation was voluntary, had the highest support.