Surface Transportation System Funding Alternatives Phase I Evaluation: Pre-Deployment Activities for a User-Based Fee Demonstration by the Minnesota Department of TransportationChapter 5. Major FindingsThis chapter presents an overview of Minnesota Department of Transportation's (MnDOT's) proposed distance-based user fee (DBUF) system and summarizes key findings and lessons learned resulting from their Phase I efforts. The findings are presented in accordance with the evaluation framework provided in chapter 4 that is based on the Surface Transportation System Funding Alternatives (STSFA) grant evaluation criteria as provided in the notice of funding opportunity.14 It is important to note that, since MnDOT's Phase I scope included pilot planning and set up activities (pilot to be implemented in Phase II), several evaluation criteria were not directly addressed within the scope of grant-funded activities. These are anticipated to be addressed with future phases of MnDOT's alternative transportation revenue explorations. As such, this chapter only discusses the attributes of the proposed system that were explored, examined, or tested in some detail during Phase I. Minnesota's Proposed System OverviewThis chapter presents the major findings of the Phase I evaluation of Minnesota's proposed DBUF concept (Figure 3). The key features of Minnesota's Phase I efforts were:

The key Phase I deliverables of Minnesota's program include the Concept of Operations (ConOps), stakeholder outreach and summary, and the 2-week proof of concept. The major findings included in this chapter are reflections of the concept developed and initial findings from the proof-of-concept demonstration. Minnesota's DBUF concept is based on leveraging inherent efficiencies of linking the road usage charge (RUC) concept with the shared mobility model, most significantly:

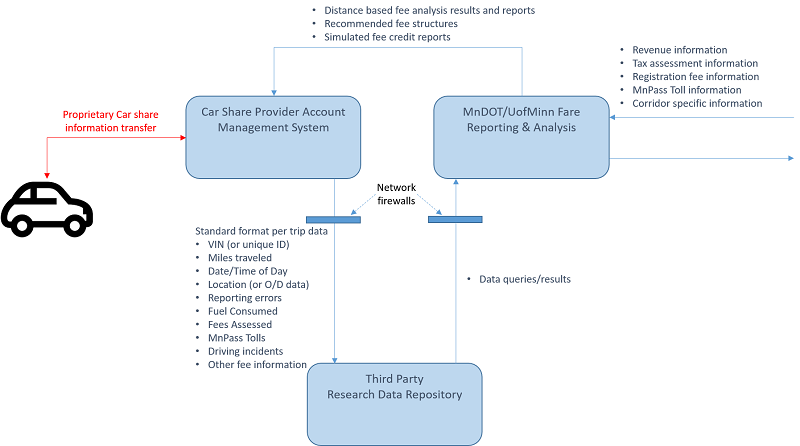

© 2016 Minnesota Department of Transportation Figure 3. Diagram. Minnesota mileage-based user fee demonstration proof of concept functional architecture. Diagram shows car shares proprietary car share information transfer with car share provider account management systems. Through a network firewall, standard format per trip data, such as VPN or unique ID, miles traveled, date/time of day, location or O/D data, reporting errors, fuel consumed, fees assessed, MnPass tolls, driving incidents, and other fee information is shared with third party research data repository. Data queries/results is shared through a network firewall with MnDOT/UofMinn Fare Reporting and analysis, who is sending and receiving revenue information, tax assessment information, registration fee information, MnPass toll information, and corridor specific information. Distance based fee analysis results and reports, recommended fee structures, and simulated fee credit reports completes the circle, being shared with the car share provider account management system.

Summary of System-Oriented ParametersThe following sections describe some of the system-oriented aspects of Minnesota's proposed DBUF model. Data SecurityData security refers to the system's data source integrity and storage as well as secure transmission and access. Collecting mileage fees directly from the shared mobility provider for the mileage driven for each vehicle does not necessitate the collection of data or information for what particular driver has made a trip. The data being collected can be based solely on the qualifying, fee-generating mileage for each specific vehicle, regardless of driver and passenger. The MnDOT system proposes to use a private third-party data repository where analysis of trip data can be used, with some data being available to MnDOT. Ultimately, the responsibility for data scrubbing will be in the hands of the mobility provider prior to turning it over to the Department of Revenue and the third-party data repository. Cybersecurity relates to the protection of information confidentiality, integrity, authenticity, non repudiation, and availability. The following proof-of-concept provisions set the basis for sound cybersecurity that will be tested with the proof-of-concept demonstration:

Charging Accuracy, Precision, and RepeatabilityThis parameter refers to the system's ability to produce a consistent assessment of fees repeatedly for identical travel. Car-sharing companies assess fees based on the time and mileage for each trip taken by a traveler. The data are already being collected using location technology that is embedded into each vehicle. In the case of a car-sharing company, the mileage and location of each trip is known and measurable. It is in the car-sharing company's best interest to collect accurate data on mileage and location. It is unknown if the location accuracy is high enough to distinguish between public and private roadways, and the accuracy may be contingent upon the sophistication of the technology being deployed by the car-share company. However, it may not matter if the fee is being defined in the same way that the fuel tax is issued, which cannot distinguish the difference between public and private roadways. Flexibility to Adapt and ExpandFlexibility refers to the ability of the technologies and systems within the proposed method to be upgraded or updated. However, the Minnesota DBUF system is not a single technology or system, but rather a series of agreements to collect mileage fees from commercial shared mobility operators. The flexibility to expand is dependent on the technology deployed by these providers. An important distinction to make is the type of mobility provider that is being incorporated into the pilot. The Minnesota project is set to use a car-sharing service, which in essence allows somebody to rent a car for a short period of time. These services typically charge users for time and mileage without regard to the location and roadways that are being used. Currently operating transportation network companies use location technologies to access additional fees for increased demand. This technology currently exists and presents an opportunity to expand how fees are assessed in different locations throughout different times of the day. While not part of Minnesota's 2016 STSFA grant activities, a fee system that applies to transportation network companies would give the opportunity to integrate demand pricing as a component of the price of the service. While the future of mobility remains uncertain, this approach allows for a high level of flexibility to adapt and expand. The DBUF system proposed is a simple mechanism for collecting fees from a limited number of commercial operators that provide a mobility service. It is neutral to the specific technologies deployed to measure the mileage driven by a vehicle. The flexibility of the system to adapt or expand is contingent on the expansion of shared mobility or mobility-as-a-service (MaaS) as a share of overall miles traveled. MnDOT's ConOps notes: By some predictions, [shared mobility] will account for 35 percent of all personal travel by 2030 and perhaps as much as 90 percent by 2040.15 Regardless of the growth of shared mobility services, the Minnesota approach is likely to develop a road map for engaging with mobility providers and other potential intermediaries such as original equipment manufacturers that will provide the direct points of mileage data collection from individual travelers. Key Finding: For the users of shared mobility services, the approach for mileage data collection and payment is likely to be flexible and adaptable. However, the adaptability of the overall approach is tied to the growth of shared mobility services.

Enforcement and ComplianceThis parameter deals with the ability of law enforcement to identify travelers that have evaded the system. MnDOT reasonably projects that the enforcement of the system would be as straightforward as the current fuel tax collection. The system's focus on commercial operators rather than individual drivers removes a significant enforcement challenge that is present with other RUC systems. The operating model of the car-sharing companies provides little opportunity for individual drivers to evade the system. The operation of the vehicle is contingent on a driver having an account set with the vehicle operator and that vehicle operator maintaining vehicle operation for each trip. To state it succinctly, these vehicles are constantly monitored by the company, and their mileage and location is always known. System CostAccording to the Congressional Research Service, one of the advantages of the Federal motor fuel tax (MFT) is that nearly all of the revenue is collected from roughly 850 registered taxpayers when the fuel is removed from the refinery or tank farm.16 In the State of Minnesota, the per gallon State fuel tax is collected from petroleum distributors.17 The total State tax rate is 28.5 cents per gallon for gasoline, diesel, and some gasoline blends. Based on the stakeholder outreach conducted by MnDOT as part of Phase I activities, the high administrative cost of a distance-based fee structure was a key concern. As such, Minnesota's approach of collaborating with and limiting points of fund collection to shared mobility providers versus a multitude of individual customers found significant support within the stakeholder community. MnDOT's ConOps states: Minnesota's approach suggests the motor fuel tax, with all its advantages and deficiencies, is likely to continue for a long time. It is challenging to design a solution for universal replacement of the motor fuel tax that begins to approach its simplicity and efficiency. The cost of collecting the motor fuel tax in Minnesota is less than 0.5 percent of the fees collected. By the most optimistic forecasts, the cost of operations and retro-fitting vehicles with technology, as well as setting up the appropriate enforcement structures for a mileage-based fee, is likely to be in the range of 5-10 percent of total fees collected. By comparison, the motor fuel tax, while imperfect, is likely to remain in place for a long time.18 Key Finding: While costs related to technology, operations, compliance, and enforcement are likely to be lower in the Minnesota approach versus some of the other pilot approaches, several categories of potential changes to administrative costs attributable to the unique nature of distance-based fee collection processes will need to be accounted for in further research and exploration.

MnDOT is currently targeting a level of cost-efficient administration between that of the State's fuel tax and the sales tax collection. If the administrative costs can be demonstrated to be lower than other RUC efforts, the Minnesota approach is likely to become more widely considered by other States, particularly those already conducting pilots. As the project moves ahead, MnDOT would need to explore categories of administrative costs or fees such as:

Summary of User-Oriented ParametersUser Privacy — Perceived and RealBoth perceived privacy and real privacy are important factors in a RUC program given the public's potential for pushback to the program based on perceptions of the program's privacy properties and the potential for actual privacy breaches. Minnesota's Phase I activities did not include a detailed examination of privacy concerns. These are planned to be detailed in the agreement with the shared mobility providers and verified through the proof-of-concept testing and future demonstrations. Privacy in a distance-based fee system pertains to:

The following inputs were collected and documented as part of stakeholder outreach (Task 5 of the Phase I program) related to stakeholders' concerns about privacy: The need for privacy during the collection and tracking of a distance-based user fee was a consistent concern of elected officials and advocacy organizations. Stakeholders recognized that tracking of individuals and their travel habits is looked upon poorly by the general public and could be a significant barrier to implementing a distance-based user fee. Several interviews discussed how using shared mobility to track distance traveled may be looked upon more favorably because tracking ride history information such as route and distance traveled are all considered features of shared mobility applications. While data tracking may be acceptable to the public when they opt into it and the information is kept by private companies, several elected officials brought up how attitudes would be different if the government tracked that information.19 The ConOps noted that public awareness and mistrust of the handling of PII is growing. The proposed demonstration model will not require government access to individual user accounts or any PII tied to individual users. Nevertheless, the MnDOT team plans to comply with industry data standards related to data protection and to perform necessary due diligence such as sanitizing PII before information is transferred from a shared mobility provider to the State. MnDOT conducted a proof-of-concept focused test of how DBUF can be collected from shared mobility and automated vehicles. In collaboration with a shared mobility provider and a research partner, MnDOT collected data from participating vehicles for the purpose of assessing whether DBUF is feasible. The data from a variety of vehicles were sanitized and aggregated and transmitted securely to a data repository. The data were then used to create simulated invoices, assessing a DBUF of miles traveled and crediting fuels tax on gallons purchased. Finally, the Department of Revenue reviewed the simulated invoices and related data to determine potential integration with existing tax collection systems and processes and to confirm auditability. According to MnDOT: The proof of concept demonstrated that it is possible to accurately capture and report travel data from a [shared mobility] provider to state agencies without impeding motorist privacy. The DBUF collection and reporting has a small footprint and does not negatively impact [shared mobility] provider operations. Existing systems and interfaces can be used to collect and report DBUF-related data. There are still open policy considerations, including how to handle federal DBUF, federal fuels tax credits, and out-of-state mileage. Ultimately, the largest takeaway from the proof of concept is that this DBUF model is viable, cost effective, and scalable for a larger implementation.20 While the approach to user privacy at this early state stage is sound, MnDOT could benefit from exploring standardized privacy policies for future demonstration. Equity — Disparate Impacts Across PopulationsMinnesota's Phase I activities did not include a detailed examination of perceived and real equity considerations. However, the following inputs were collected and documented as part of stakeholder outreach (Task 5 of the Phase I program): The issue of equity in implementing a distance-based user fee can mean different things to different people. Representatives from Transit for Livable Communities, now known as Move Minnesota, and the Association of Minnesota Counties were both concerned about the disparate impact a distance-based user fee would have on low-income individuals. Concerns about the inequity for rural versus urban users were discussed during interviews with two politicians but both thought that this issue was addressed with this project. Two politicians brought up the issue of fairness to drivers with electric vehicles and vehicles that get different gas mileage… Advocacy organizations and elected officials agreed that the issue of where any money raised is spent is important. Two politicians wished to ensure the funding is dedicated to transportation related projects and not spent elsewhere. Several interviewees brought up the need for current recipients of gas tax revenue to continue to receive funds even if a distance-based user fee is implemented.21 The MnDOT program could benefit from exploring and analyzing the following equity considerations along with preparation for deployment:

Exploring the above equity considerations would involve examining potential adverse impacts, developing mitigation approaches, and designing education and outreach initiatives to address stakeholder concerns regarding such issues. As the demonstration takes shape, Minnesota could also benefit from assessing the public's perception of equity and fairness of the RUC approach. As noted in National Cooperative Highway Research Program Synthesis 487, Public Perception of Mileage-Based User Fees (2016), equity and privacy are key concerns of the public. This synthesis, which reviewed results from 38 surveys and 12 focus groups, concluded that the public has numerous questions about the fairness and equity aspects of a RUC, including:

The evaluation team held the opinion that Minnesota may wish to use this set of questions as a starting point to design an evaluation of how residents in the State perceive the equity and fairness of a RUC. For example, these questions and related concerns could form part of a future focus group study and other forms of public feedback and input. Key Finding: The key equity issue to explore in the future phases would be evaluating the implications of the scenario in which electric vehicles continue to be widely personally owned instead of being part of the shared mobility fleet, thus eliminating the possibility of collecting any revenue from them (fuel tax or mileage fee).

Ease of Use and Public AcceptanceThe degree to which a system is straightforward, easy to use, and accepted by public has been identified as a critical user need in MnDOT's ConOps. Under the Minnesota concept, public acceptance of the proposed model has two aspects:

Acceptance by Shared Mobility Customers: For acceptance by shared mobility customers, ease-of-use measures would include:

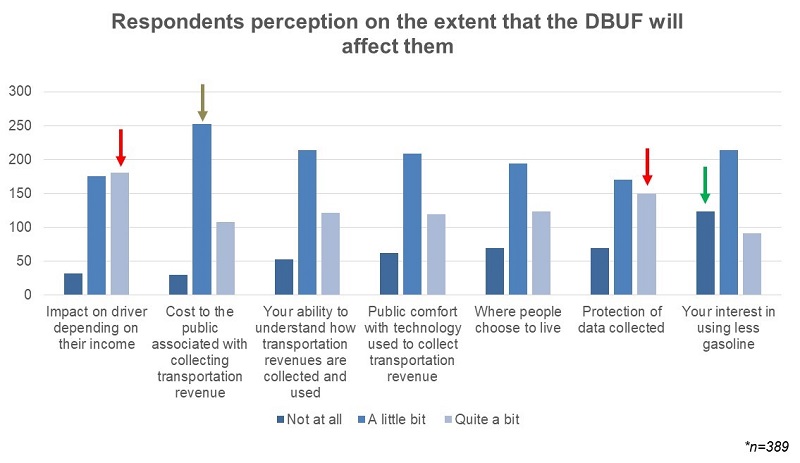

Acceptance by Shared Mobility Providers: For acceptance by shared mobility providers, ease-of-use measures would include a system with non-intrusive to regular operations that is easy to integrate with existing systems. Minnesota, in coordination with MnDOT, conducted a survey to determine perceptions of car sharing members. Of the approximately 400 survey respondents, most were either slightly knowledgeable or not knowledgeable about the funding structure of Minnesota's transportation system, and a majority had not heard about DBUF. Figure 4 shows the survey respondents' perception on the extent that a DBUF will affect them.  © 2016 University of Minnesota, Humphrey School of Public Affairs Figure 4. Chart. Survey respondents' perception on the extent that a distance-based user fee will affect them. Additionally, the survey found that 40 percent of the respondents have concerns related to DBUFs. The key concern is how their data will be protected. The respondents also shared concerns about impact on low-income communities and shared mobility services. The survey also found that, while a large number of respondents asked for more information before being able to express support for DBUF on all vehicles, the level of support for the concept increased when the question was posed about DBUF implemented through shared mobility services. Additionally, when asked about the impact of DBUFs on the use of gasoline, a good number of respondents mentioned that DBUF would not incentivize less use of gasoline. Likewise, MnDOT identified the following questions to explore further in future tasks:

14 USDOT Notice of Funding Opportunity Number DTFH6116RA00013, issued on March 22, 2016. Available at: <https://www.grants.gov/custom/viewOppDetails.jsp?oppId=282434>. [ Return to note 14. ] 15 Navigant Research. 2013. "Autonomous vehicles: self-driving vehicles, autonomous parking, and other advanced driver assistance systems: global market analysis and forecasts." [ Return to note 15. ] 16 Congressional Research Services. 2016. Mileage-Based Road Usage Charges, Washington, DC. Available at: <https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44540.pdf>, last accessed April 25, 2019. [ Return to note 16. ] 17 Minnesota House Research Department. "Highway Finance" (website). Available at: <https://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/pubs/hwyfin.pdf>, last accessed April 25, 2019. [ Return to note 17. ] 18 Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2018. Minnesota Distance-based User Fee Demonstration Plan, Concept of Operations, 90% Draft Final, St. Paul, Minnesota. p.11. [ Return to note 18. ] 19 Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2018. Distance-based User Fee, Task 5 Report, St. Paul, Minnesota. [ Return to note 19. ] 20 Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2019. Minnesota Distance-based User Fee Demonstration Plan, Proof of Concept Report, Version 1.3, St. Paul, Minnesota. [ Return to note 20. ] 21 Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2018. Distance-based User Fee, Task 5 Report, St. Paul, Minnesota. [ Return to note 21. ] 22 Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2018. Minnesota Distance-based User Fee Demonstration Project, Draft Concept of Operations, St. Paul, Minnesota. [ Return to note 22. ] 23 McKinsey & Company. 2016. Automotive Revolution — Perspective Towards 2030 How the convergence of disruptive technology driven trends could transform the auto industry. [ Return to note 23. ] 24 Shared Use Mobility Center. 2017. Twin Cities Shared Mobility Action Plan. Available at: <https://sharedusemobilitycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/SUMC_TWINCITIES_Web_Final.pdf>, last accessed April 25, 2019. [ Return to note 23. ] |

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||