Advancing TSMO: Making the Business Case for Institutional, Organizational, and Procedural Changes

Part III. Agency Leadership Support for Key Institutional, Organizational, and Procedural Changes

The Role of Leadership

Most Departments of Transportation (DOT) have made many improvements in their Transportation Systems Management and Operations (TSMO) activities that can be carried out by TSMO staff (i.e., activities not requiring Institutional, Organizational, and Procedural (IOP) changes beyond TSMO staff span of control) without the need for preparing and communicating a formal business case. However, as described above, the nature of IOP changes is that they often involve actions requiring top management support or initiative; therefore, many require making the business case in terms related to concerns of top management.

Even in the few cases where formal business cases have been prepared (as part of formal TSMO Program Plans), TSMO IOP changes may still have difficulty gaining traction. This is especially true if the case to advance TSMO has not been developed in terms sufficiently compelling to overcome a DOT Chief Executive Officer's (CEO) reluctance to expend their in-demand time and attention that is required to understand the needs of TSMO, to support the necessary changes in policy, and to authorize and support specific actions needed to facilitate certain IOP changes.

Given the limited tenure of the CEO position at most DOTs and the accompanying effort to address a wide range of agency-related priorities over a short amount of time, it is not surprising that TSMO must compete with other agency activities for CEO attention and support. Leaders may question if the efforts, disruptions, and associated risks of departing from long-standing conventions are worthwhile, especially given the often less visible nature of TSMO projects and limited awareness of the potential payoffs. This section addresses these challenges, providing insights into how to tailor a business case for IOP in terms related to the leadership audience.

Tailoring the Business Case to Leadership

Insights for Working with Leaders to Make IOP Changes to Advance TSMO

A DOT director's timeline should be considered as a sequence of actions that build on one another. Generally they may have four years to accomplish what they set out to do, so taking preparations to get TSMO on their radar early on, and capturing the initial energy of their term, may be very beneficial in building progress. Strategies for exposing directors to TSMO include: using case studies of or peer exchanges with high achieving TSMO States to learn from and apply what those States are doing (this could also infuse the TSMO discussion with some extra energy), or to frame TSMO as a strategy for pursuing low-cost, easy, and early (quick turnaround) wins for their term (i.e., fix a bottleneck). From there, the focus should turn to institutionalizing the easy fixes by establishing performance monitoring to show how the easy fix has long term impacts on safety and travel time. A third step is then to protect the program or staff from CEO changes by not associating the program as something owned by the CEO, but rather the right thing to do for the DOT. This step reinforces the institutionalization of the approach and TSMO.

The changes in DOT institutional orientation, culture, and arrangements required to develop and support more efficient and effective TSMO necessarily involve top management—those agency leaders with the authority to make the types of key adjustments as noted in part II, section 7.

Increasingly, agency directors or CEOs include both highway agency career professionals who have risen up in the organization, as well as externally-appointed officials coming from outside the agency and, in many cases, from outside transportation. In both cases, there are challenges in making the business case for the needed top-down changes.

- For career CEOs, it is likely that their success has been built on their effectiveness in managing the legacy agency programs (project development, construction, and maintenance) and fully understanding every aspect of agency structure and management.

- For externally-appointed CEOs, their appointment typically reflects management experience and understanding of overall State government which may or may not have included experience with the State DOT program—much less TSMO.

In either case, many CEOs may lack a clear understanding of TSMO—its importance, the justification for it, and the substance of TSMO programs and approaches. The business case therefore must serve the roles of supporting increased familiarization, understanding, and commitment on the part of leaders as the basis for top management-led change towards implementing more effective TSMO—by justifying the proposed changes to both elected officials and agency senior management in terms relevant to their interests and priorities.

It should be noted that the lack of familiarity with, or commitment to, TSMO is not a reflection on a CEO's capabilities. Agency leadership must grapple with a wide range of both immediate and long-term policy, funding, management, and political priorities that can consume available CEO time and attention Any given set of top management priorities reflects the reality of finite leadership time and relative perceived risks and benefits. In many cases, TSMO is, or will be, perceived as an unfamiliar new enterprise with a limited track record that provides modest payoffs with low public and political visibility and the risk associated with introducing changes that may not be justified. In addition, given that (on average) State DOT CEO turnover is between two and three years, it is not surprising that there is a tendency for leadership to focus on issues that maintain continuity and reflect well-accepted priorities. TSMO champions may, therefore, need to explain the benefits of TSMO and how it helps a DOT manage risks and mitigate congestion and safety challenges. The business case is an opportunity to do that.

Understanding "Leadership Capital"

Making the business case to top management involves special challenges. By definition, senior decisionmakers, such as DOT chief executives, have responsibility for broad policy and program issues. TSMO is only one of many concerns and one that may not initially appear to be significant to the agency mission and credibility. In addition, the type of IOP changes essential to more effective TSMO may require a special focus not easy to obtain. It is important to understand top management orientation and tailor the business case to it.

Public administration literature sometimes uses the concept of "political capital" to define, as a scarce resource, the credibility that is either accumulated from seniority or endowed by position and is an important component of their authority. Similarly, "leadership capital" can be used to understand the store of time, attention, and capability that can be brought to bear by a leader on any particular issue to foster change. For DOTs, leadership capital can be usefully subdivided into "reputational" and "representative" capital. In addition, "intellectual" capital can be considered. For each type, a range of payoffs, risks, and rewards is involved:

- Leader Reputational Capital. Agency leaders achieve and maintain their institutional positions and authority (both formal and informal) by maintaining the overall external image of an agency in terms of reliable and stable execution of the agency's understood mission. This reputation is based, in part, on the legacy and promise of institutional achievement within the context of political and stakeholder support. These two aspects are important to both supporting a leaders' career success and in maintaining agency external support. It is, therefore, natural that the time and attention of a leader is focused on activities and investments that support the agency's reputation with minimal risk.

- Leader Representative Capital. Agency leaders establish and maintain their authority (formal and informal) and credibility within the agency based not just on experience and seniority, but also on supporting a stable and effective organization in terms of its structure of hierarchy and authority. This authority is based, in part, on respect for the established positions and roles of the other key players within the organization and the tacit support of key managers (and their direct reports), within the organization. It is natural that leaders are extremely cautious about making changes that may suggest instability and or disturb existing relationships.

- Leader Intellectual Capital. DOTs are professional organizations built around a legacy culture of technical expertise—typically, expertise in civil engineering. The introduction of new technology and concepts, such as TSMO, may involve the challenge of the unfamiliar. The inherent degree of uncertainty surrounding these new technologies and concepts, as well as the effort required to collect reliable information and gain confidence for informed decisionmaking, may cause top management to hesitate in making the needed IOP changes.

Each of the above forms of leadership capital is a scarce resource. In making the business case to leadership it is important to understand how the payoffs and risks may be perceived from a top management point of view and what type of leadership capital expenditure is involved as a framework for targeting supportive arguments as appropriate.

Leadership Actions to Support Institutional, Organizational Change

In light of top leaders' orientation as described above, it is important to focus on key IOP changes that may be dependent on supportive leadership, or, in other words, that are in the span of control of leadership. This section provides some general considerations for leadership actions in each of the three IOP areas. Procedural changes, many of which are within the span of control of middle management, require only modest support from top management. Organizational changes, which may disrupt other agency units, suggest the importance of leadership persuasiveness in the ability to build a top management consensus supportive of TSMO. Institutional changes make the greatest demand on leadership capital, as it involves being able to articulate the payoffs from some significant changes in policies and programs, both internally and externally. A general discussion is followed by a table describing key leadership actions and the nature and level of leadership capital involved to advance TSMO IOP.

Institutional: Building a Culture that Values and Supports TSMO

Leadership Levels

The importance of leadership—CEOs, chief engineers, division heads—relates to the reality that IOP changes involve the fundamental rethinking of the agency's mission and objectives, and together changes how TSMO gets done on day-to-day basis. Some of these may seem at odds with the agency's legacy culture with its civil engineering and capacity project focus, even though TSMO can contribute to more effective targeting of new capacity and more efficient maintenance procedures.

Leading and managing changes usually requires a combination of staff champions and top management support. The CMM workshops indicated the range of levels in leadership and its importance as a key ingredient in making the important IOP changes:

Level 1: Individual staff champions promote TSMO.

Level 2: Jurisdiction's senior management understands the TSMO business case and educates decisionmakers/the public.

Level 3: Jurisdiction's mission identifies TSMO and its benefits with a formal program and achieves wide public visibility/understanding.

Level 4: Customer mobility, reliability, and safety services accepted as a formal, top level core program of all jurisdictions with agency commitment and accountability.

A key challenge is that both champions and leaders turn over. Therefore integrating TSMO into policy as well as related procedures and organizational changes can formalize these changes to institutionalize TSMO into the agency.

The needed organizational and procedural adjustments (as discussed in part II, section 5) may require adjustments in institutional orientation that require strong and informed leadership. In this the business case can play a critical role. This is especially important as a unique role of top management is to develop an internal consensus and external support for the changes and resources required for effective TSMO.

Top-down change management support, to be effective, must be rooted in a clear understanding on the part of leadership of the TSMO mission and objectives as being an agency priority. This is further emphasized in today's safety and reliability challenges and in the opportunities for new combinations of technology and processes to deal with them. Key focus areas for leadership include:

- Explicitly including TSMO in the Agency's Mission—Fundamental to ensuring a long-term commitment to, and the continuing improvement of TSMO is embedding it in agency policy, along with appropriate objectives and performance measures. Agency strategies and resource allocations are presumed to be policy responsive, and effective TSMO must be part of explicitly stated agency priorities, along with development and maintenance of the infrastructure, if it is to play its appropriate cost effective role. Changes in policy must be sponsored by top management and include extensive buy-in by leadership throughout the agency.

- Marketing TSMO, both internally and externally,is an important use of the unique influence and leverage of top management. It also clearly demonstrates that the commitment to TSMO is truly at the agency level.

- Facilitating Collaboration often requires top management support through heading up inter-agency collaboration initiatives, at the agency head peer-to peer level, to align transportation-related public agencies (law enforcement, emergency response, etc.) with the DOT TSMO objectives.

- Public-private partnerships, which are in some cases needed to access key technical resources, also involve clear policy decisions regarding outsourcing and the level of external dependence.

Organizational: Reorganizing and Staffing to Support the Needed Transportation Systems Management and Operations Business and Technical Processes

The organizational and staff adjustments required to effectively execute may require important organizational structure and staffing changes as detailed in part II. Advancing TSMO as a program requires a clear allocation of responsibility to ensure that there is effective coordination, responsibility, and accountability. Thereby a chain of command that silos engineering from operations is a considerable handicap to continuous and coordinated improvement of a TSMO program that promotes technology development as the basis for operational management.

Key focus areas for leadership include:

- Revising Organizational Structure—The development of the appropriate organizational structure may require adjustments in roles, responsibilities, allocations of resources, and even policy priorities that cut across all agency programs. There are alternative models for allocating responsibility, but they have a common need for continuous coordination in both program development and program operations. The identification of the single point of responsibility and chain of command at the overall agency (or district/region) level of who has been endowed with the appropriate mix of responsibility and authority is needed to clearly place TSMO in the organization. The nature of these changes requires initiative and support at the top management level.

- Allocating Needed Staff Resources—"Staffing up" for TSMO may require reallocation of existing positions, an increase in Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs), or a redefinition of certain positions, especially where specific technical capabilities are required. In addition, top management attention may also be important to develop or expand existing training programs with the appropriate resource allocation. Top management attention may also be important in making adjustments regarding existing position descriptions and job classifications or adding new ones, to support hiring and retaining the necessary skillsets for advancing TSMO.

- Supporting TSMO Champions—Experience indicates that staff champions play a key role in promoting TSMO, raising the profile of TSMO in the agency and with leadership, identifying issues and opportunities, and facilitating and maintaining formal and informal collaboration. This is especially critical in the earlier stages of TSMO program development where IOP changes are important. Effective TSMO programs are often dependent on middle management leadership that have been identified, authorized, encouraged, and supported by leadership.

Insights from Interviews with State DOT CEOs on IOP Arrangements for TSMO

The following insights for increasing the traction of TSMO among agency executives were collected during discussions with current and former DOT executives.

- The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) New CEO program offers a potential point of intervention. This program uses presentations/discussions with existing CEO veterans as a device to sensitize new CEOs to key perspective to increase their prospects for success.

- Consider branding issues related both to how TSMO is described and the confusing jargon that seems disconnected to typical CEO priorities.

- Have tools "on the ready" for incoming CEOs—most likely provided by AASHTO at the new CEOs orientation. Ideas include:

- TSMO needs to be rebranded, not necessarily a shiny new abbr or advertising campaign, more so a core definition and understanding of what TSMO is. "We don't build the system out anymore, we operate and manage it."

- Present TSMO in terms of an operational management evolution—this should address from what to what to show evolution.

- Have a very short handout for new CEOs to explain what TSMO is and how it will make a CEO a "hero," by effective response to transportation events such as major incidents and storms and through deployment of low cost, quickly implemented, strategies with proven benefits, and working with your essential partners in unison.

- Recognize the discussion of key IOP changes is not the leading point—and is appropriate as it may emerge from peer discussions/examples and follow-up activities that show it is needed.

- Package TSMO for what it is for the forward thinking CEO: big data, as a predecessor to connected and autonomous vehicles requiring many of the same policy and program commitments, and capabilities, etc.

Procedural: Changes to Business and Technical Processes

Business and technical processes associated with TSMO are substantially different than those developed to support capital construction and maintenance, and are often not a natural fit with traditional agency IOP arrangements. Some changes to traditional processes, or development of some new processes, are often needed to support effective TSMO. Oversight from leadership is typically an important component to making these adjustments to legacy processes where TSMO involves real-time management of operational strategies. Since TSMO strategies often address causes of congestion and delay that are not addressed by capacity improvements, they need to be considered in both the planning and project development processes to ensure simultaneous consideration for the most cost effective combined application of both capacity and operational measures.

Developing, maintaining, and updating TSMO strategies requires the development of concepts of operation and ITS architectures based on systems engineering that must be understood and applied by staff experts to ensure system interoperability and appropriate technology.

Other processes, especially situational awareness and performance measurement, are critical to TSMO to determine its effectiveness at any given point in time, and over time. The function of transportation management centers (TMC) that operate the network in real-time symbolizes the distinct features of TSMO, compared to a project development-oriented engineering organization. Unlike conventional capacity improvements, effective TSMO strategies require "tuning up" in real-time and periodic check-ups to ensure that the various procedures and protocols are being combined and applied at their greatest effectiveness in response to changing conditions.

Many of these IOP interdependencies are not intuitively obvious, and an important role of the business case—from a senior leadership perspective—is to clarify the need for the appropriate directions of managed change.

Key Leadership Actions related to IOP Changes

Tables 9 to 11 identify key leadership actions in each of the IOP dimensions together with the demands they place on the expenditure of leadership capital. The action items on this table are consistent with the table of actions by CMM dimension (part II, tables 1 through 6).

The columns in the tables below are organized by the principal categories of needed top leadership action. They present the potential payoffs from each as well as the leadership commitment level (the requirements on top management attention and authority) and the likely time frame for accomplishment. Finally, the table summarizes what kind of leadership "capital" expenditure may be involved in the action.

A Case Study of TSMO Leadership: Colorado Department of Transportation

In 2012 the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) began taking serious actions to reassess and improve how it approaches TSMO. These actions were in large part spurred by TSMO champions at the executive level—in particular CDOT's executive director—from 2011-2015. To jump start its formal TSMO program, CDOT established the Division of TSMO in 2013 with a new TSMO Director position on par with legacy division directors. The new TSMO Director was then charged with defining CDOT's TSMO goals, evaluating its current TSMO activities, and recommending the organizational changes, investments, and immediate actions needed to improve TSMO.

While there are many potential motivations and justifications for improving TSMO activities, CDOT created a TSMO business case that reflected the unique context of its agency, its customers, and the State of Colorado. For CDOT, a key selling point was that the state can no longer build its way out of pressing congestion and safety issues due to time and cost constraints. By investing in TSMO, CDOT is therefore "buying the most mobility at the lowest possible cost" and offering real solutions in the near term, rather than years to decades down the road. For CDOT it was also important to communicate that approximately 55 percent of urban congestion and virtually all rural congestion is due to nonrecurring congestion—and that TSMO solutions are ideally suited to solve exactly this type of congestion.

A key element in CDOT's initial transition was the visible and active support of the executive director. At the first Steering Committee meeting, the actions of CDOT's then Executive Director were described as follows in a CDOT report:

"[The Executive Director] opened the workshop by reiterating his support for improved operations and the benefits that can be gained by operating the transportation system more efficiently and effectively. He stated that CDOT created the Division of TSMO in order to provide the organizational structure and support to strategically deliver operations in a more integrated and effective manner and that the Transportation Commission strongly supports this goal and has allocated $75 million over the next five years to support the program. He stated that the Chief Engineer also supports this project. Finally, he extended his appreciation to the Steering Committee for taking time to be involved in this very important project."

The Steering Committee established by the executive director undertook a systematic stepwise program to install the essential IOP elements. To focus the planning and recommendations of the new TSMO Division, CDOT first created its own definition of TSMO and delineated the 12 most important "core operational areas" for Colorado: (1) Freeway Management, (2) Arterial Management, (3) Travel Demand Management, (4) Maintenance Management, (5) Work Zone Management, (6) Law Enforcement Coordination, (7) Traffic Incident Management, (8) Commercial Vehicle Operations, (9) Communications Infrastructure Management, (10) Data Management, (11) Asset Management, and (12) Transportation Planning Coordination. To establish a baseline, CDOT graded the current activities within each of the core operational areas. All areas received a grade in the "C" or "D" range, with the exception of Maintenance Management and Traffic Incident Management, which both received a B-minus. From here, CDOT found it necessary to either implement new responsibilities within the Division of TSMO or implement changes within the larger CDOT organizational structure in order to improve their grade in each core operational area. (No change in organizational structure was also considered, but ultimately dismissed, for each core operational area.)

This led to the creation of detailed recommendations for each core operational area at the individual program level—as well as a list of recommended investments and intermediate goals for the near future (Fiscal Year 2014).

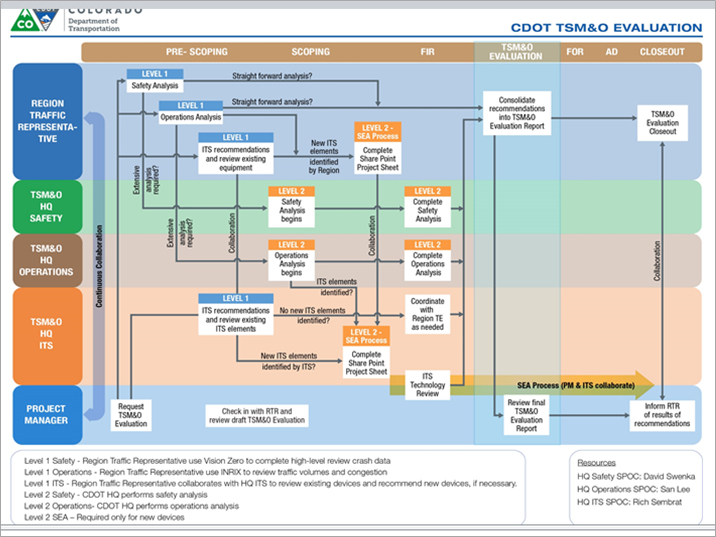

A key feature supporting these TSMO-supportive improvements was the formal incorporation of TSMO evaluation into the agency's formal project development process. The purpose of the directive from the executive director was to ensure that:

- The TSMO Evaluation consists of three parts; Safety, Operations, and ITS analyses.

- The TSMO Evaluation Process is aligned with the CDOT Project Development Process and will be included in the manual.

- The TSMO Evaluation will evaluate the project area and make recommendations to the project team for improvements related to Safety, Operations, and ITS.

Beginning January 1, 2016 all projects with a Design Scoping Review on or after February 1, 2016 will require a TSMO Evaluation.

Figure 8. Graph. Schematic of the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) Transportation Systems Management and Operations (TSMO) Evaluation.

(Source: CDOT, https://www.codot.gov/business/designsupport/bulletins_manuals/adg/tsmo.)

As early as fall 2015, CDOT was already seeing the fruits of its labor. In this time, the reorganization helped the amount of dedicated TSMO funding surge from around $8 million/year to over $60 million/year. This early success has been attributed to both the executive level champions and newly offered TSMO training programs, which created a culture much more conducive to effective TSMO activities. In the following years, CDOT continued to build on this success. The agency has found that its IOP changes to support TSMO have helped facilitate the implementation of a series of high return-on-investment TSMO projects, with benefit-cost ratios typically around 10:1 and as high was 40:1. Overall, CDOT's reorganization and associated IOP changes have helped—and continue to help—the department make great strides in advancing TSMO as an integrated, systematic part of transportation planning in Colorado.