Active Traffic Management (ATM) Implementation and Operations Guide

CHAPTER 4. IMPLEMENTATION AND DEPLOYMENT

This chapter provides a review of the approach to implementing and deploying active traffic management (ATM) strategies in a region. Particular topics include legal issues, stakeholder engagement, and public outreach and involvement. This chapter presents the following sections:

- Construction and Scheduling. This section describes construction strategies associated with ATM, including how an agency may build the ATM solution.

- Legal Issues. This section reviews any circumstances under which a regional agency may face legal limitations that will need to be addressed prior to implementation and deployment.

- Stakeholder Engagement, Public Outreach, and Involvement. This section discusses the importance of stakeholder engagement throughout the implementation and deployment process for ATM strategies.

4.1 CONSTRUCTION AND SCHEDULING

Once a project is at the implementation stage, construction and scheduling play a key role in a successful rollout. The following subsections provide an overview of various project-related topics associated with construction and scheduling.

Project Delivery

Agencies continue to adopt alternate delivery vehicles for ATM deployments and, in some cases, alternate finance and funding methods. Table 14 provides examples of different project delivery methods that could be used for ATM projects, though the examples may not necessarily be specific ATM projects.(66) Additional consideration for project delivery includes involving ATM with existing reconstruction or maintenance projects. ATM could be used as a tool to assist with directing traffic on, off, and along a freeway during construction. A number of strategies as well as devices could be implemented depending on the need of the contractor and the length of the project. The devices implemented could consequently remain after the reconstruction/maintenance project has been completed and then utilized for operational needs. Implementing during this stage may reduce the overall total costs for an ATM system since it would not be a full build. Additional phases could be implemented at a later stage once additional funding is available.

|

A software or system deployment procurement using federal-aid funds may be an engineering or service contract rather than a traditional construction contract. Engineering is defined as professional services of an engineering nature as defined by state law. For engineering contracts, qualifications-based selection (QBS) procedures in compliance with the Brooks Act must be followed. Service contracts (non-construction, non-engineering in nature) are to be procured in accordance with the Common Rule (49 CFR Part 18) (https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2009-title49-vol1/pdf/CFR-2009-title49-vol1-part18.pdf). |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design-Build (DB) |

|

|

Virginia, Washington (system minus gantries) |

| Design-Bid-Build (DBB) |

|

|

Washington (gantry only), Minnesota |

| Design-Build-Operate-Maintain (DBOM) |

|

|

Virginia |

| Construction Management at Risk (CMAR) |

|

|

Arizona (Phoenix Downtown Traffic Management System) |

| Public-Private Partnership (P3) |

|

|

Denmark, England, Germany |

In a design-build (DB) context, the DB solution provider will participate earlier in the project development. Depending on the scope of services defined, the role of the DB team can range from supporting to leading any of the individual elements of the project development. While most of the operations and specific ATM strategy coordination—such as law enforcement agencies, first responders, and tow recovery services—typically would be handled by the agency (or on behalf of the agency by consultants or contractors), it is expected that the DB team would play a large role upon appointment. Alternatively, the selected delivery method could be a design-build-operate-maintain (DBOM) solution where the scope would include operations and maintenance responsibilities. The DBOM team would be involved with the development of SOPs and the integration of maintenance activities for ATM components in coordination with current ITS and roadway operations and maintenance.

While DB and DBOM represent options for project delivery, the agency remains the ultimate owner of the facility (as with the traditional design-bid-build approach). In the concessionaire model, which could part of a DBOM or P3, a third-party concessionaire typically operates the facility under a long-term lease. In such an arrangement, the concessionaire takes on many of the obligations and liabilities as the owner. As such, the concessionaire will have an even greater stakeholder responsibility. This includes a larger public outreach and marketing role, especially if there is the option of revenue generation through toll collection as a component of the facility. Additionally, the concessionaire becomes responsible for the establishment of formal memorandums of understanding with local transportation agencies and local law enforcement and public safety agencies.

|

Information on the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Major Project Delivery Process for some innovative delivery methods is available on FHWA's website (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/majorprojects/defined.cfm, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/alternative_project_delivery/defined/). |

These delivery methods involving a concessionaire may be appropriate for projects that involve tolling, such as the I-4 Ultimate project in Orlando, Florida that includes express toll lanes, (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/project_profiles/fl_i4ultimate.aspx) or the Capital Beltway High Occupancy/Toll (HOT) Lanes on I-495 (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/project_profiles/va_capital_beltway.aspx), which could also incorporate ATM strategies as part of the deployment. To support success of the ATM implementation, the relationship between the concessionaire and the ultimate end owner must be well codified in the concessionaire agreement. Additionally, the relationships between the two must be cultivated during the design and build phases of the project to prepare for operations on day one. The agreement should include conditions that mitigate the likelihood of the concessionaire to operate with certain financial motives (e.g., to generate revenue sufficient to finance borrowing costs and/or to generate an operating profit).

CMAR contracts provide benefits when transportation improvements are needed immediately, and when the design is complex, difficult to define, or subject to change and/or has several design options.(67) They are also beneficial when a high level of coordination is needed with external agencies, which may be applicable to ATM projects.

Coordination

During implementation, a crucial partner to involve in all facets of the project implementation will be the contractor. The contractor should be a leader in facilitating the stakeholder coordination effort. Many of the attributes of a good contractor are self-evident and follow well-known project management practices. These include:

- Ability to prepare and maintain a proper resource-weighted schedule with a clearly delineated critical path.

- Establishment of proactive, frequent, transparent communications with clear and unambiguous progress reporting.

- Development and maintenance of thorough documentation through delivery of as-built plans.

- Understanding of systems integration and systems testing and access to systems integration and network specialist resources throughout the life of the project.

- Strong and ongoing relationship with software provider throughout life of project.

- Establishment of proactive risk management and risk mitigation program.

- Proactive engagement with third parties that may impact project critical path, such as resolution of utility conflicts and acquisition/coordination of power connections.

- Proactive coordination with other projects in study area and incorporation of those activities into project schedule and risk management plan.

- Proactive approach to permitting that mitigates schedule risks.

- Willingness to consider value engineering approaches when technology changes lead to potentially improved processes or other changed conditions lead to mutually beneficial modifications.

- Establishment of in-place standard operating procedures and the management structure to support the implementation of those SOPs effectively throughout the contractor team.

- Establishment of a well-defined, strong, documented, and enforced safety program.

The effectiveness of the contractor team will have a direct impact on the progress of the project implementation. All coordination efforts should be reflected within the overall project schedule and managed through a partnership between the owner agency project manager and the contractor. This coordination will be especially critical for elements such as software integration, training, and maintenance.

For agencies with mature freeway management systems and incident management programs, it is likely that there are forums, processes, and communication channels in place to facilitate stakeholder interaction—including regional incident management committees, ITS and technical reference manual committees, and regional ITS and transportation demand management committees. When available, these existing stakeholder coordination mechanisms should be leveraged and modified when necessary to support implementation of the ATM corridor. This may include additional coordination meetings, working sessions focused on the ATM corridor, and expanded membership to include partners not previously involved. In locations where such forums or processes do not exist, it is suggested that one or more standing committees be established to maintain scheduled information sharing, information dissemination, risk management, and issue resolution around the operations, maintenance, and outreach for ATM corridor construction.

|

Existing forums, processes, communication channels, committees, and coordination structures can be leveraged and modified to support implementation of ATM strategies on facilities in region with mature freeway management systems. If these efforts do not exist, their formation can help facilitate the effective implementation of ATM in a region. |

Schedule

Schedules are critical on any project, but ATM projects involve a complexity of coordination that increases the criticality of the schedule for an effective delivery. A traditional freeway-focused intelligent transportation systems (ITS) project can experience a delay with minimal or no impact to the day-to-day operations of the facility. A delay in delivery of the ITS solution would only extend the time frame at which the public begins to receive traveler information or when an agency can more effectively manage incidents. The benefits of the project are real and valuable to the public, but the direct impacts on the operation of the facility are not as easily felt.

In a typical ATM deployment, the technology component is an integrated portion of the operation of the facility. Similar to a traffic signal for an arterial roadway, the ATM components—whether they are variable speed limit signs, lane control signals, or adaptive ramp meters—are an integrated part of the facility. In addition, ATM implementations often involve civil components such as shoulder lane improvements, ramp improvements, and gantry and sign structure installations. Delays associated with these civil components easily can impact the daily operation of the facility. Last, the culmination of all subsystems including the civil elements, field equipment, and central software must align to deliver a complete solution.

|

The complexity of ATM projects increases the need for coordination. ATM technology components must be integrated into existing operations , which be significantly impacted by schedule slippage on civil components. Schedule adherence and close risk monitoring can help facilitate on time ATM project delivery. It is also essential to maintain operations during construction, and ATM can reduce the impacts of construction if operational throughout. |

Thus, schedule adherence and schedule risk monitoring are critical to the success of an ATM project and require a coordinated schedule that addresses the field construction; central office construction and integration; operations and maintenance training and SOP development; formal partnership agreement codification; education and outreach campaign launch and continuation; and software integration into operations, which includes testing, debugging, and training.

Coordinating civil elements within the corridor is crucial to maintaining operations of the facility during construction(68) and includes a large structural engineering and foundation footprint that must be coordinated with existing structures and overhead signing. Roadbed construction must be phased to maintain traffic during tasks such as shoulder enhancements, ramp enhancements, and accident investigation. Last, the frequency of structures along the corridor must be coordinated to ensure signing consistency as new ATM dynamic and static signage is integrated with existing dynamic and static signage. It also is important that construction of these civil elements occur in coordination with other projects in the vicinity of the corridor.

Component-level subsystem and system testing and training are critical elements that should be integrated within the project schedule as well. Often, these soft elements are programmed for the end of the project delivery life cycle and receive less emphasis than the more tangible elements. However, for a successful first day of operations, it is crucial that system testing be completed in a timely manner and that all operations, procedures, and protocols be aligned with the defined system and associated software.

Schedule is a critical component for any project, and most agencies and contractors use extensive tools and methods for monitoring schedule adherence. When compared to a traditional ITS project, ATM projects typically involve a larger civil component, the introduction of new subsystems and technologies to support traffic management, and a more intense software component to support the corridor. Managing these additional complexities warrants an enhanced risk management regime. In such a regime, all project risks are quantified and rated by probability of occurrence and impact of occurrence. Risks can be noted as either a threat or an opportunity for the project. Once identified and rated, a risk response plan should be developed, including the assignment of an appropriate mitigation response. Risk management, analysis, prioritization, and mitigation strategies should be ongoing parts of project management throughout the development and implementation of the project. The frequency of revisiting and updating the risk management plan should be commensurate with the size and pace of the project.

4.2 LEGAL ISSUES

ATM deployments may have legal implications. An agency should review laws, regulations, and policies at the local, State, and Federal levels that are relevant to ATM to determine whether the planned ATM strategies fit within the existing legal and policy framework for the local area if changes or additional policies are needed.(69,70) For example, dynamic speed limit (DSpL) and potential automated enforcement, use of shoulders as a travel lane, and ramp metering may all have legal implications. Thus, an agency should assess the legal authority to enforce ATM strategies as well as whether law enforcement and legislative parties are willing to support the enforcement of the ATM strategies.(70) In cases where supporting laws and policies are not in place, it may be necessary to gain the buy-in of higher-level agency stakeholders and elected officials before an ATM strategy can be deployed.

Agencies have taken various approaches to address the legal aspects of ATM. For example, a number of States allow some form of dynamic shoulder use during congested periods, including bus-on-shoulder operations.(71,72) However, policies vary by State and facility regarding the vehicle types, allowable design exceptions, and other restrictions imposed on the use of shoulders as a travel lane.(71,72) In some areas, policies regarding a minimum posted speed limit may restrict the enforceable variable speed limits that can be posted.(73) In Missouri, the variable speed limit signs were blank when speeds were below 40 mph (before the system was deactivated), while in Minnesota and Washington, the ATM signs may also post variable speeds of 35 or 30 mph.(73) Pennsylvania provides an example of policy that supports variable speed limits to improve safety, with code 212.108 (Speed Limits) stating, "Speed limits may be changed as a function of traffic speeds or densities, weather or roadway conditions or other factors."(70) The Pennsylvania code also states that "variable speed limit sign shall be placed … at intervals not greater than 1/2 mile throughout the area with the speed limit."(70)

|

ATM deployments may have legal implications that an agency should ensure are addressed prior to implementation. Strategies such as dynamic shoulder lanes and variable speed limits, along with enforcement approaches, can present operational challenges of legal authority or appropriate policies are not in place. |

Some ATM strategies may require operational changes within the agency that require modifying existing agency operating policies. While some ATM strategies may use automated systems, others may require operator verification or validation, particularly those related to ATM signage or dynamic shoulder use operations. Because it is very apparent to drivers when ATM signage is not accurate, agencies have an increased responsibility to ensure that appropriate, timely, and updated information is presented to retain motorist confidence.(61) To mitigate this concern, Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) employed additional transportation management center (TMC) staff, and Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) cross-trained additional TMC staff to ensure 24/7 coverage.(61)

Agencies may need additional staffing and/or equipment to facilitate operational changes. For example, dynamic shoulder use operations might need additional freeway service patrols and law enforcement to ensure rapid incident response since the shoulder may not be available as a refuge area.(71,73) For truly dynamic shoulder use operations that allow 24/7 use of the shoulder during congested periods, an operator, enforcement, or freeway service patrol personnel will likely need to be available at all times to verify, either in person or using closed circuit television (CCTV) cameras, that the shoulder lane is cleared of debris and stalled vehicles prior to opening it to traffic. ATM deployments may also require additional staff for maintenance of the system.(73) Snow maintenance operations may be impacted by dynamic shoulder use operations due to the need to plow more pavement area and less area to place the snow.(73)

4.3 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT, PUBLIC OUTREACH, AND INVOLVEMENT

Regional stakeholders are a critical contributor to the success of ATM strategies. Because ATM strategies will likely be new to most stakeholders and the public, an outreach program to provide information on the purposes, benefits, operation, and performance outcomes of ATM strategies will help build trust in the investments.(13) This engagement and outreach can take on many forms, and various aspects of this activity can help garner stakeholder and public support and thus ensure a successful ATM deployment.

Identifying Stakeholders

As an ATM project deployment moves forward, agencies need to reach out to various stakeholder groups to help ensure a successful deployment. These groups should be engaged early and often in the project planning process to ensure understanding, support, and successful deployment.(73) Stakeholders should include policy makers and staff from transportation agency divisions that will be responsible for deploying, operating, and maintaining the ATM system. Outside of the deploying agency, stakeholders include any agency or group that may be affected by the ATM deployment, including the public at large. Potential stakeholders may include but are not limited to:

- State, county, and city transportation agencies.

- Metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs).

- FHWA Division Office.

- Highway service patrol/contractors.

- State and local law enforcement.

- Fire departments and emergency medical services.

- Transit agencies and operators.

- Other incident management agencies.

- Elected and appointed officials.

- Media.

- Traveling public.

The role and level of involvement of individual stakeholder groups will certainly vary from project to project, but all may be able to offer valuable insight and help generate support for a project. Many stakeholder groups will have already been identified if the area has a regional intelligent transportation systems (ITS) architecture, which might be a good starting point for establishing a core team to further define the ATM strategy.(74)

As an agency works to identify stakeholders, a project champion who can serve as a de facto spokesperson for the project and work to engage others to generate support within and beyond the deploying agency may emerge. The project champion might play various roles, including initiating a feasibility study, establishing a dialogue with other stakeholders, and helping establish support for the project across a broad range of audiences. Implementers of ATM strategies in California, Minnesota, and Washington have all attributed their successes to a strong project champion who built working relationships and teamwork among various agencies to implement these strategies.(74)

|

ATM project stakeholders can come from a variety of agencies and entities throughout a region. Project champions often emerge from these stakeholders, and can play a key role in advancing the dialogue associated with a project and contribute to a successful deployment. |

Establishing a Stakeholder Team

An agency may want to consider formally organizing an agency stakeholder team to establish collaborative support for a project. Initial efforts may include a peer exchange workshop or webinar with other agencies that have successfully deployed similar ATM strategies. Such events can be useful for an exchange of ideas, lessons learned, and best practices. The collaborative support of multiple agencies will be useful for gaining support of elected and appointed officials, media, and the public.

Smaller working groups may be developed and convened regularly to keep stakeholders informed about the progress of the deployment. These working groups can facilitate keeping agency stakeholders informed, creating opportunities for input and participation, providing feedback, creating an informed consensus, and identifying the need for system adjustments during deployment.(74)

Engagement, Outreach, and Involvement

Buy-in from multiple levels of staff at stakeholder agencies can provide a basis for outreach to the public, media, and elected and appointed officials. Outreach to both the public and broader agency stakeholders is elemental to building the needed trust and gaining general acceptance of ATM strategies.(75) Gaining the support of agency decision makers and policy makers helps make the ATM project easier to move forward, particularly if there is a collaborative agency group willing to advocate for the ATM strategy with elected and appointed officials.(74) Outreach to elected and appointed public officials is important in various settings and helps these individuals understand the benefits of the ATM strategy. Their support will be needed to provide funding or to promote changes to legislation or new policies that will allow ATM strategies, such as dynamic shoulder use, variable speed limits, and nonstandard language for dynamic lane control signage.(74)

Various avenues of communication can facilitate this outreach and understanding, including one-on-one meetings, presentations, newsletters, and emails. Table 15 provides examples of outreach and engagement efforts that agencies across the country have undertaken to advance ATM projects in their region. The overall intent of all of these approaches is to ensure that all stakeholders have a common understanding of the purpose and objectives of a proposed ATM project prior to informing the public.

|

Outreach videos for various projects are available online from WSDOT (https://youtu.be/mIpPJrOeZyg), VDOT (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zO_wNNkZOTg&feature=youtu.be), Wyoming (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ywrLjvEYyk), and Highways England (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_C5oDYA6hkY&feature=youtu.be). |

| Agency | Project(s) | Sample Outreach Approaches/Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Highways Agency (UK) |

|

|

| MnDOT |

|

|

| Queensland Government (Australia) |

|

|

| VDOT |

|

|

| WSDOT |

|

|

| WYDOT |

|

|

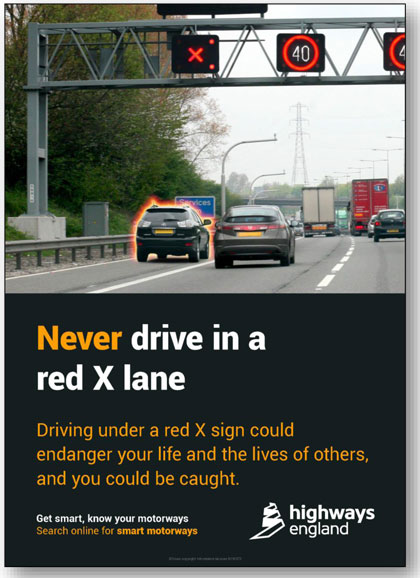

An example of the WSDOT ATDM website is shown in Figure 26, while the YouTube channel hosted by Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) for the I-66 visualization videos is shown in Figure 27. A brochure prepared by Highways England to educate the public on the use of the red X is depicted in Figure 28.

Figure 26. Illustration. WSDOT ATDM website.(76)

Figure 27. Photo. VDOT YouTube channel with ATM visualization videos.(77)

Figure 28. Illustration. Highways England brochure for red X.(78)

ATM strategies are likely to be new to most stakeholders and the public, which presents challenges when agencies want to communicate with stakeholders to gain support.(61) Implementing agencies need to educate stakeholders and the public so that they understand the potential benefits of an ATM system and do not make negative assumptions. To facilitate communication about an unfamiliar concept, many agencies create special branding for the new initiatives, which may involve hiring a communications specialist to work with the agency and community to develop appropriate messages and marketing materials to use for outreach, education, and public awareness.

A deploying agency must also determine the amount and type of public outreach to pursue to inform the public about ATM. The level of public outreach will depend on the scale, complexity, and potential level of controversy of the ATM deployment. For example, ATM deployments involving new and unfamiliar dynamic signage, such as dynamic lane use control (DLUC), dynamic shoulder lane (DShL), dynamic lane reversal (DLR), dynamic junction control (DJC), and variable speed limits, require a public education focus. Conversely, ATM strategies such as adaptive signal control, queue warning (QW), or adaptive ramp metering (ARM) will likely not require any public outreach because they are either transparent to the system user or easily understandable.

Lessons Learned

In recent years, various agencies with experience implementing ATM have undertaken a variety of outreach efforts and have had varying experiences worth noting. In general, ATM public outreach efforts have two thrusts: to promote the ATM strategy that can offer benefits, and to educate travelers on proper usage of an ATM strategy. It is important for agencies to plan for public interaction in both the planning and deployment stages to keep the public informed and receive feedback. Agency outreach efforts should:

- Concentrate on providing information on whether a project is worthwhile.

- Consider travelers as allies and advocates for ATM and not just roadway users.

- Use a broad range of mechanisms and tools for information dissemination.

- Share the successes of completed ATM projects.

- Ensure effective communications via the delivery of consistent messages by all levels of the organization.

- Include policy- or legislative-related changes that might impact enforcement procedures.

WSDOT and MnDOT both used a wide variety of outreach approaches for their respective ATM projects—including workshops, forums, one-on-one meetings, group presentations, media advertising and outreach, newsletters, and emails—to provide information to the public, commuters, and policy makers about their new ATM strategies, in conjunction with new tolling initiatives..(79,80) WSDOT had a very positive experience with local media stations to broadcast coverage on why ATM signage technology is good but found it hard to maintain that message.(61) Additionally, WSDOT quickly realized that it was important to focus on safety benefits to be gained from ATM signage as opposed to other, less clear objectives such as speed harmonization.(61) WSDOT noted that while outreach advocates for specific projects, it can also lay the groundwork for future projects and concepts.(73)

Agencies deploying ATM strategies also emphasize the importance of maintaining consistent terminology and messaging, which should be determined early in the project planning stages.(73) For example, Missouri DOT (MoDOT) found success in outreach by targeting three key areas: expectations, enforcement, and media relations.(73) Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) found value in educating law enforcement and other emergency responders early in the planning process and then having them accompany agency staff when meeting with the media.(73)

|

ATM Application: VDOT developed a comprehensive outreach package to share information about the I-66 project in suburban Washington, DC. As part of this outreach campaign, VDOT prepared the following:

|

You may need the Adobe® Reader® to view the PDFs on this page.