Elements of Business Rules and Decision Support Systems within Integrated Corridor Management: Understanding the Intersection of These Three ComponentsChapter 3. Case Studies And Lessons Learned In Integrated Corridor Management With Emphasis On Decision Support Systems And Relevant Business RulesIntegrated corridor management (ICM) provides information that covers the entire transportation network to help commuters make better decisions about how to travel in that corridor. This section focuses on best practices in ICM deployment with respect to decision support systems (DSS) and business rules. SAN DIEGO AND DALLASAs mentioned in the previous chapter, agreements and memoranda of understanding among agencies, known as business rules, are structural and key elements of success within the context of ICM. However, few determinate examples exist. Nevertheless, even implicit rules must exist for agencies to share data, resources, and—most importantly—real-time action plans. The sections below explain how the San Diego and Dallas ICM demonstration sites operated with either documented or implicit "business rules." Business RulesDallas. The business rules for Dallas were initially based on a regional ITS cooperative agreement that was expanded to an operations and maintenance agreement, as described by Spiller et al. (2014, page 9-1): A blanket ITS cooperative agreement for the region was in-place and used as a starting point by the ICM stakeholders for this project. The ICM program was a part of the transportation improvement project to ensure regional support by the Council of Governments. An operations and maintenance (O&M) document was developed cooperatively among all the operating agencies in the corridor during the operations phase of the ICM demonstration. The ICM O&M Manual has the potential to act as a more detailed agreement. The Dallas stakeholder team included:

These agencies and stakeholders have been participating in incident management and regional training for many years (Spiller et al, 2014. Page E-2). They have established multiagency working groups and committees to promote multiagency cooperation, including an ICM steering committee, ICM operations committee, and an ICM 511 committee. Within the region, the North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG) includes a transportation committee and an ITS committee. The stakeholders' committee was also created as a multijurisdictional oversight and advisory committee. It was noted that interjurisdictional challenges included identifying ongoing capital sources, maintaining operational capacity, and funding maintenance activities. DART was initially selected as lead agency. Existing operations staff is used for the daily operation of the system. The ICM coordinator, provided by DART, leads the ICM responses. The DART high- occupancy vehicle (HOV) operations team is co-located with TxDOT at the DalTrans facility. The other operating agencies (i.e., DART bus, light rail, North Texas Tollway Authority, and cities) operate out of their normal operations center (Spiller et al, 2014. Page E-3). San Diego. In San Diego, the foundational documents were more numerous and included a project charter and MOUs: Throughout the project process several documents have been undertaken and are anticipated to be completed as they pertain to the data collection/documentation, lessons-learned experienced through the ongoing operations. Initial related documentation included the completion of a project charter, followed by the completion of individual [memoranda of understanding]. Such documents provided high-level guidance on needed coordination and cooperation. During the design and development of the [integrated corridor management system (ICMS)], the focus turned to the needed operational consensus. Such agreements were documented through agency-level memorandums, which served as the platform for an ICMS operational framework document. The operational framework establishes and sets the conditions for using the individual network assets under the ICMS environment and reflects input/agreement by all partner agencies (Spiller et al, 2014. Page E-30). The ICM implementation was also not without interjurisdictional challenges: There is no one specific challenge that stands out since all challenges experienced were generally dependent on each other. However, the observation to share is that the greatest challenge was associated with ensuring that the project partners received appropriate transportation, engineering, and operational input, which was then translated into the software design process during the [integrated corridor management system] design (Spiller et al, 2014. Page E-30). According to Spiller et al. (2014, page E-31), the San Diego ICM Team established these multiagency working groups/committees:

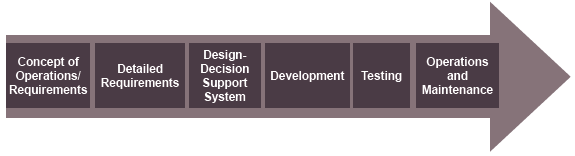

Decision Support System DevelopmentA main component of each of the U.S. Department of Transportation (U.S. DOT) ICM demonstration projects was the development of a unique DSS to facilitate decision-making activities and operations in order to minimize the impacts of their respective congestion challenges. The San Diego and Dallas ICM Pioneer Sites were the very first sites to deploy ICM systems with a combination of DSS methodologies. These methodologies included table-based, expert systems, event scenario matrices, custom rules-based systems, and systems that were model driven or data driven. These types of DSS had been implemented in different intelligent transportation systems (ITS) projects across the country. The lessons learned from these efforts as well as an assessment of which methodologies work best under certain conditions had been documented by the U.S. DOT in a report titled Assessment of Emerging Opportunities for Real-Time Multimodal Decision Support Systems in Transportation Operations: Concept Definition and Current Practice. According to this report, each site had unique conditions; therefore, it was necessary to explore the appropriate methodologies based on the regional differences. Dallas. Dallas implemented a customized, rules-based DSS that was built on an expert system approach with an event scenario matrix. The San Diego site also used a rule-based methodology with incident response parameters and knowledge-based information on roadway geometry and device locations to generate response plans. The rules were created with operator inputs. Overall, DSS uses the strategy responses developed by the stakeholders, expert systems, prediction modeling, and evaluation components to recommend plans of action associated with specific events (Table 1). Although not explicitly detailed, these approaches should incorporate business rules given the coordination needed amongst different entities. The DSS is part of the design development stage of an ICM. Figure 14 shows the Dallas ICM phases of development.  Figure 16. Diagram. Dallas integrated corridor management phases. (Source: Miller et al., 2015) The Dallas ICM developed a set of pre-approved response plans, which can be a type of business rules based on agreements between agencies. These response plans were seen as key to implementing coordinated ICM operations and responses. There were several committees tasked with developing these response plans (namely, ICM operations, decision support, and arterial monitoring systems). The group would discuss certain event types and locations that would require different response scenarios depending on the location and transportation impact. Although not explicitly stated in the Dallas ICM reports, it is implied that these response scenarios could very well involve key stakeholders, who represented different agencies, as well any agreements or protocols. The following approach was used to develop the response plans:

The report lists magnitude-of-event indicators that stakeholders used to develop appropriate strategies in response to incidents, including:

Note that several of these indicators are related to local roads, park-and-ride lots, and transit operations. Each partner would have its own magnitude-of-event protocols to incorporate information sharing and cooperation. Table 5 depicts decision strategies for minor and major incidents and delay.

NA = not applicable.

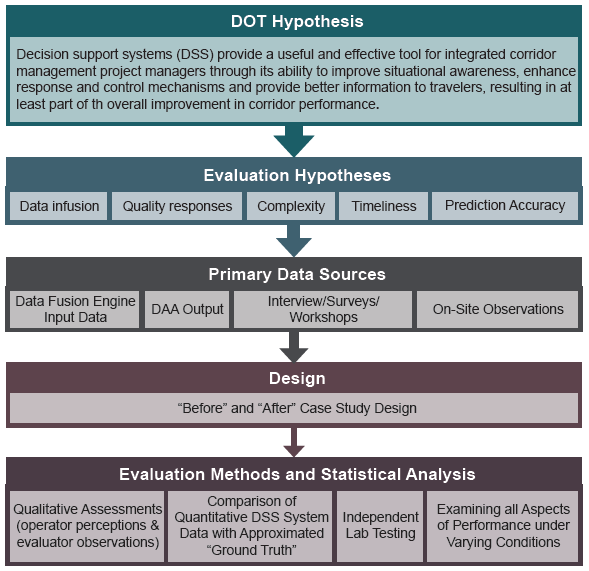

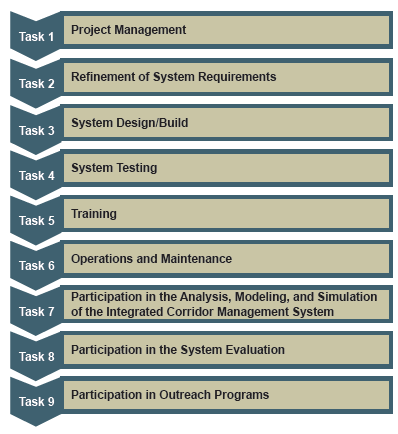

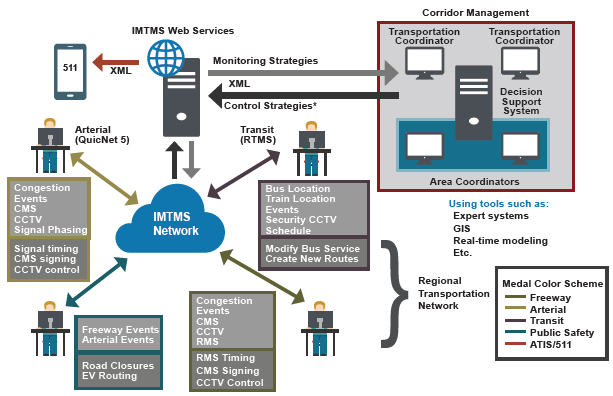

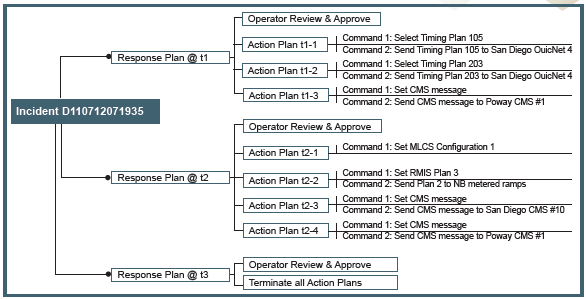

(Source: Miller et al., 2015) The Dallas DSS consists of expert rules, prediction, and evaluation. The operating agency stakeholders provide candidate response plans based on their experience and knowledge, which are then selected by the expert rules system. Note that these operating agencies would have their own protocols, and the DSS could be enhanced by including these agreements (i.e., business rules) to enact select response plans as well as implementation. At the next stage, a candidate response plan is submitted to the ICM coordinator, who decides whether or not to enact it. This would also be an area where business rules could have a significant impact on plan selection. For example, if the DSS regularly submits plans that are not realistic due to constraints based on interagency agreements, then the ICM coordinator will not be as likely to rely on it for future decisions. After selection, the response plan is then pushed to agencies for implementation. Dallas has developed and approved over 400 response plans, with more currently being written and revised as a result of experience. The ICM processes provide partner agencies with the pre-approved response plans both in real-time via the Internet during response plan implementation as well as offline for assessment and refinement. Figure 17 depicts an overview of Dallas DSS analysis from hypothesis to evaluation. For more information, please refer to the Dallas Decision Support System Analysis Test Plan.  Figure 17. Diagram. Overview of a decision support systems analysis. (Source: Lee et al., 2012) San Diego: In contrast, the San Diego ICM already had a decisionmaking system based on enabling the sharing of information across agencies. But, the application needed to integrate this information into actionable control strategies—an element which was lacking. The DSS attempted to fill this gap by providing data integration capabilities with a decision-making process for developing response plans. Unlike pre-DSS practices, this new tool incorporates coordination among corridor stakeholders, which is a significant and important development. Note the referenced actions are being coordinated and not carried out in isolation. This implies some sort of agreements need to be built into the decision-making process, either at the response development stage or at the response selection stage. Figure 18 illustrates the list of contracted tasks for the California Partners for Advanced Transportation Technology (PATH):  Figure 18. Diagram. Partners for Advanced Transportation Technology tasks One of the objectives was to develop the DSS, the network prediction system (NPS), and the real-time simulation system (RTSS). (Dion, Skabardonis, 2015) Network Prediction System (NPS) – developed as part of the ICM demonstration to support DSS operations and used to predict origin-destination flows within the I-15 corridor. Real-Time Simulation System (RTSS) – developed as part of the ICM demonstration to support DSS operations and used to manage and execute corridor simulations. Source: Dion, Skabardonis, 2015 Figure 19 depicts the underlying concept for a DSS. Dion and Skabardonis (2015) note that the diagram: ...provides an early conceptual view of the DSS. Core functions of the DSS are represented in the gray box shown in the upper right corner of the diagram. Based on information received from the various transportation systems via the IMTMS web services (shown in the blue boxes surrounding the IMTMS cloud), the DSS would use a rules engine to assess corridor operations and develop suitable response plans. These plans would then be converted into control actions that would be passed back to the relevant systems via the IMTMS web servers. Examples of control actions that may be received by each transportation system are shown in the grey boxes surrounding the IMTMS cloud.  ATIS = advanced traveler information system. CAD = computer aided dispatch. CCTV = closed-circuit television. CMS = changeable message sign. EV = emergency vehicle. GIS = geographic information system. IMTMS = intermodal transportation management system. RMS = ramp meter stations. RTMS = regional transit management system. xML = extensible markup language. Figure 19. Diagram. Decision support system concept. (Source: Dion, Skabardonis, 2015) Note that the DSS would receive information from various transportation systems, which could include protocols and procedures for interagency interactions. It is also possible that these interagency agreements and business rules were not incorporated (or incorporated inconsistently) because each agency may only be supplying the information relevant to their system. Figure 20 shows an example response plan concept from the San Diego ICM demonstration project report.  Figure 20. Diagram. Response plan concept from the San Diego integrated corridor management demonstration project report. (Source: Dion, Skabardonis, 2015) The following description is from the San Diego ICM report:

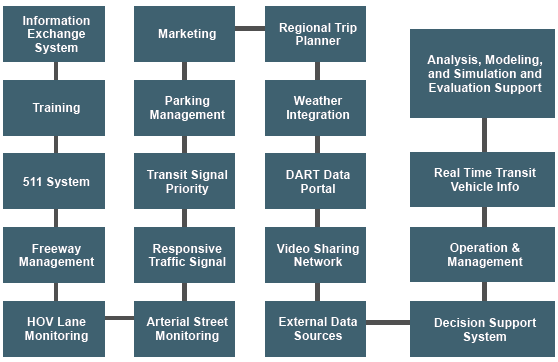

Figure 21 and Figure 22 represent elements of Dallas ICM demonstration and implementation, respectively. Figure 23 depicts multiple stage implementation of ICM.  Figure 21. Diagram. Elements of the Dallas integrated corridor management demonstration.  Figure 22. Diagram. Integrated corridor management multiple stage implementation.

Figure 23. Diagram. Elements of the Dallas integrated corridor management implementation. Expected TimeframeDallas:

OTHER GRANT SITESThis section gives a brief overview of ICM and potential business rules-related issues in several of 13 sites selected to receive ICM grants in 2015 from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). They were required to use the funding towards pre-implementation activities; e.g., development of systems engineering plans and concepts of operations, et al. Table 5 lists the 13 sites, their respective lead agencies, and their respective ICM project corridors.

Source: Federal Highway Administration, "The U.S. Department of Transportation Announces $2.6 Million in Grants to Expand Real-Time Travel Information in 13 Cities." Available at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/pressroom/fhwa1504.cfm

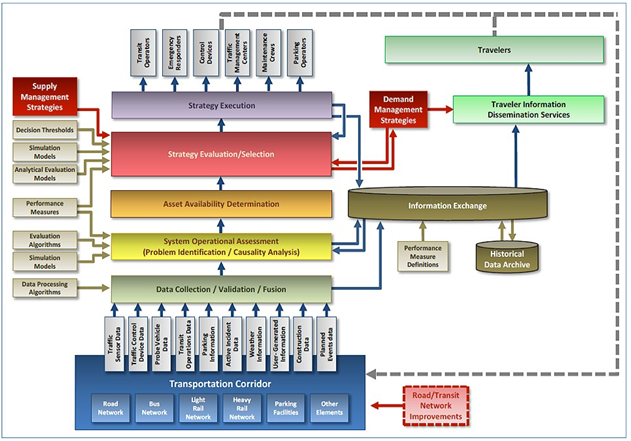

As of 2017, most of these sites have now completed or are near completion of their pre- implementation activities. In the context of this report, the Los Angeles I-210 ICM deployment is notable because the Los Angeles deployment team built on lessons learned from the Dallas and San Diego prototype demonstration projects. Future ICM deployments can also be expected to build on these earlier efforts and advance the state of the practice in DSS and business rules. Dion, Butler, and Xuan (2015) illustrate their concept of how a fully developed ICM system would work in Figure 24 and explain it as follows:

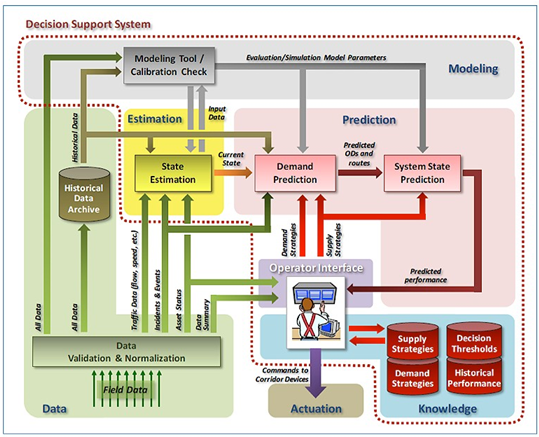

For purposes of this paper, we shall focus on the DSS element, especially the selection and evaluation of management strategies. Figure 24 indicates a variety of components that fit into the DSS, but does not note the incorporation of business rules through interagency agreements, etc.  Figure 24. Diagram. Functional view of a fully developed integrated corridor management system. (Source: Dion, Butler, Xuan, 2015) Figure 25 illustrates an operational concept for a decision support system. It contains a diagram of the decision support system which would evaluate and select appropriate management strategies for implementation. Several key functionalities were listed, including:

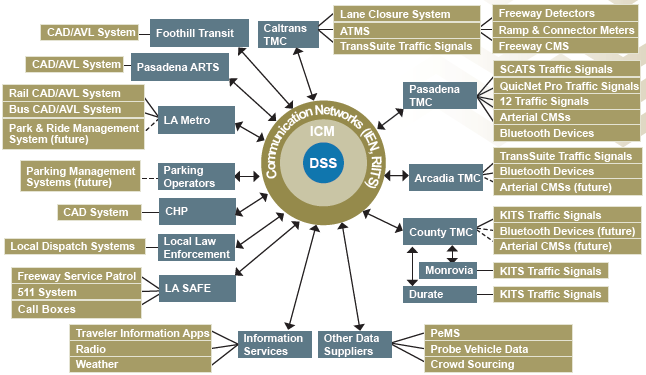

Figure 25. Diagram. Operational concept for a decision support system. (Source: Dion, Butler, Xuan, 2015) Similar to the earlier diagram, there is not a specific area showing the importance of incorporating business rules into system development. The description mentions operators making selections amongst recommended scenarios, so it is possible that this is where the incorporation of interagency agreements and business rules occurs. If so, the load on the operator could be reduced by preemptively removing conflicting recommendations that do not work efficiently in the coordinated environment. As noted in chapter 2, communication is a vital component of both proper ICM development as well as DSS implementation. Figure 26 presents a preliminary, high-level concept for an ICM deployment on I-210 Los Angeles. Note the range of partners and stakeholders, including roadway and transit operators, law enforcement and first responders, information providers, parking operators, and other data providers. Also note the vital role both communications networks and DSS support, located at the center of this diagram, play.  ARTS = area rapid transit system. ATMS = advanced transportation management system. CAD/AVL = computer-aided dispatch/automated vehicle location. CHP = California Highway Patrol. CMS = changeable message sign. KITS = Kimley-Horn Intelligent Transportation System Software. PeMS = (Caltrans) Performance Measurement System. TMC = traffic management center. Figure 26. Diagram. I-210 pilot integrated corridor management preliminary high-level architecture. (Source: Dion, Butler, Xuan, 2015)

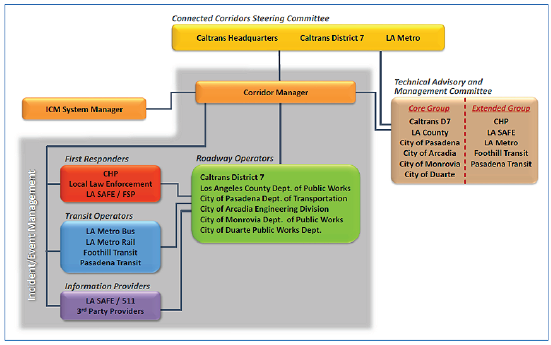

CHARACTERISTICS OF SUCCESSFUL INTEGRATED CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT IMPLEMENTATIONSEffective LeadershipA key component of any successful organizational plan is engagement among knowledgeable leadership and staff who are capable of operating and creatively applying decisions in unpredictable, complex environments. Integrated thinking about capabilities across all areas—understanding the benefits, risks, and implication of different scenarios—must become a standard practice for leaders. Engagement opportunities among transportation control centers and both public and private agencies will promote leadership skill development. Leaders need to be motivated and have the time and resources to become more familiar with all partners. Peer exchange workshops are a great way to achieve the culture shift necessary to support an integrated operation. Bringing representatives with the knowledge of ICM implementation in other regions can provide the training for staff new to the concept. Cooperative Working Relationships with Federal, State, and Local AgenciesAs noted in Gonzalez, et al., (2012), trying to manage the complexity of an ICM implementation is a serious challenge. It entails bringing together multiple agencies that use a diverse set of operations methods. Further, a range of subsystems that must be coordinated often exist within agencies. It is important to increase communication and organization to ensure that all project partners agree about expectations. A systems management approach is also useful when developing and organizing this highly complex structure. The systems engineering approach often entails the development of a plan that all stakeholders agree to early in the project process. It provides a common understanding of how work will be managed and supports tracking systems development activities from one phase to another. This same approach can be used in developing interagency agreements, which can then be incorporated into the DSS. In their evaluation of stage 3 of the ICM deployment on I-210 in Los Angeles, Dion, Butler, and Xuan (2015) identified the following key groups of individuals as part of an institutional framework:

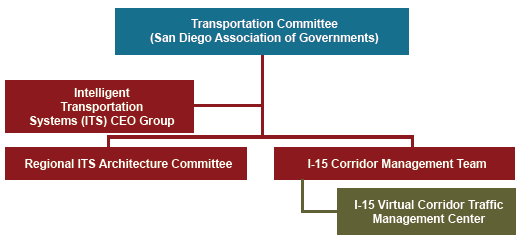

CHP = California Highway Patrol. ICM = integrated corridor management. Figure 27. Diagram. Hierarchy of the I-210 connected corridor steering committee. (Source: Dion, Butler, Xuan, 2015) Figure 28 is another example of institutional framework of the San Diego I-15 ICM system in California.  Figure 28. Diagram. Institutional framework for the I-15 integrated corridor management system. Program Enhancement StrategiesEnhancement strategies directly emanate from innovations in ideas, personnel management, and leadership development. Here are a few examples of how to improve ICM system reliability:

Performance measures are another way to evaluate the success of the ICM strategies and operation. How to select proper performance measures that are related to the ICM goals and objectives have been explained in detail in the FHWA document Concept of Operations for the I-15 Corridor in San Diego, California. Staff ExpertiseStaffing is an important consideration for any new program, and agencies have staffed ICM efforts in a variety of ways. These can include hiring new staff or adding ICM duties to existing staff. The lead coordinator is the personnel or office which serves as the daily manager of operations overseeing the status of ongoing daily ICM deployment. He or they review and inspect the resultant response plans. An ICM deployment may or may not have a lead coordinator identified as such; however, by some measure, one person or one office from one of the member agencies is probably filling this role by rote. The lead coordinator is also the person or office that one calls to inquire about the ICM operation or program. This person may or may not be the champion previously described, or necessarily an employee of the lead agency. The lead coordinator may retain prior job duties for his or her employer. It is probable, however, that those job duties (new or continuing) would naturally tailor to serve this purpose anyway, only now on behalf of the affiliated ICM agencies (Spiller et al. 2014, page 3-3). LESSONS LEARNED AND COMMON MISTAKESDue to the complex environment of an integrated, managed corridor, as well as the ever-changing technological and organizational landscape, there are a variety of lessons learned from common mistakes that agencies have encountered in their implementation sites. It is our hope that these lessons can be passed along for the benefit of an agency considering incorporating business rules into a DSS for their regional integrated corridor project. It should be noted that many of these topic areas are broad and may go beyond just the business rules and interagency agreement included in this guidance document, but are mentioned for their potential impact in the larger landscape. For example, in a final report on the Dallas ICM, the authors stated that the lessons learned focused mainly on larger institutional issues and relationships that are universal to any region considering an ICM (Miller, et al., 2015). It is important to build on existing institutional arrangements in an attempt to build consensus, developing clearly defined roles and responsibilities along with tempered expectations. Within these boundaries, establishing clear business rules as part of the decision process can facilitate operations. Figure 29 shows the recommendations to enhance DSS. 1) A decision support system (DSS) may not take into account certain jurisdictional rules about what cab be communicated to travelers (some jurisdictions do not allow for direct diversion messages with instructions to be communicated, instead favoring less specific messages). This can have a major impact on the efficiency of a traveler information dissemination strategy recommended by a DSS.

2) Many jurisdictions may restrict truck use on certain roads. A DSS that has not incorporated this information and interagency agreements regarding truck traffic would not differentiate the traveler type. A properly calibrated DSS should incorporate this into the recommendation protocol to separate out vehicle travelers from truck traffic in any diversion or messaging suggestion.

3) There could be local jurisdictional constraints on the use of traffic signals and diversions at certain times. For example, in San Diego there were safety concerns about traffic being diverted past schools around school start and end times. These concerns and restrictions are contextual constraints of the chess board that the DSS should be accounting for when providing recommendations.

4) For traveler information posted to dynamic message signs, there are often regulations regarding the structure and format of messages. This should be incorporated into the DSS recommendations. Although constraining the message content and structure to conform to local signs and protocol is likely part of the DSS development, additional rules for types of messages and phasing frequency based on traffic speed may be the type of agreed upon use that is not usually incorporated.

5) Something as simple as traffic management center (TMC) staffing is another area where not all jurisdictions operate in the same way. Recommendations should incorporate whether staff from other facilities are available to coordinate with (and if not, is thee another representative or agency that the responsibility rolls to) would enhance the need for operator review and adjustments.

Figure 29. Infographic. Recommendation to enhance a decision support system. Table 7 summarizes lessons learned from the ICM implementation pilots. The following sections draw heavily from reports, presentations, and experiences from the Dallas and San Diego ICM implementation sites (Miller et al., 2015, Dion and Skabardonis, 201,5 Gonzalez et al., 2012).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||