Shared Mobility: Current Practices and Guiding Principles

Chapter 2. Overview of Shared Mobility Services

Introduction

Shared mobility is having a transformative impact on many cities by enhancing transportation accessibility, increasing multimodality, reducing vehicle ownership and vehicle miles traveled (VMT) in some cases, and providing new ways to access goods and services. Several trends are impacting the growth and mainstreaming of shared mobility, as highlighted below.

Labor and Consumer Trends

Source: Thinkstock Photo

Changing labor trends are impacting the transportation and mobility. In recent years, a growing number of part-time workers are working increasingly varying schedules, making traditional morning and afternoon peak commutes less predictable (McClatchy Tribune Services , 2013). Additionally, direct changes in travel behavior, such as a greater number of workers telecommuting, more consumers shopping online, and growth in telemedicine may represent some of the most notable shifts. Advances in information technology, such as video conferencing, instant messaging (IM), virtual private networks (VPNs), collaborative scheduling, screen sharing, and cloud computing, are increasing the frequency and extent of telecommuting. Similarly, online commerce is growing rapidly and comprising an increasing percentage of total retail activity. The U.S. Census reported quarterly e-commerce retail sales for the first quarter of 2015 were $80.26 billion, representing 7 percent of all retail sales. New food and grocery delivery services, such as those offered by Safeway, Instacart, AmazonFresh, and UberEATS, may reduce inner city grocery and food travel. According to the market research firm Packaged Facts, approximately three in 10 consumers have ordered items for same-day delivery in the past 12 months, excluding food ordered for immediate consumption (Packaged Facts, 2015). Telemedicine is one emerging trend that may also alter non-work travel, particularly for non-discretionary trips. Telemedicine may reduce the need for some trips through tools, such as video conferencing of doctor visits with patients, e-transmission of diagnostic images, remote monitoring of patient vital signs, online continued medical education, nursing call centers, and web-based applications.

Additionally, the increased use of for-hire vehicle services (e.g., taxis, ridesourcing, and microtransit) and a greater reliance on just-in-time delivery platforms, such as CNS and direct business to consumer (B2C) delivery (e.g., Amazon and Ebay), are also impacting travel behavior. Together these services-coupled with real-time information and mobile technologies-continue to encourage last-minute planning and on-demand or instant modal and delivery selections.

Technological Trends

Source: Thinkstock Photo

Increasing use of smartphone and Internet-based technologies, the prevalence of intelligent transportation systems (ITS) technologies, and the mass marketing of connected vehicles can help to improve efficiency.1 In recent years, there has been a growing use of smartphone and Internet-based platforms to facilitate shared mobility and multimodal transportation options more broadly. A Pew Research study found that as of January 2014, 90 percent of American adults had a mobile phone, and 58 percent had a smartphone. As of May 2013, 63 percent of American adult mobile phone owners used their phone to go online, and 34 percent predominantly use their mobile phone for Internet access (Pew Research Center, 2014). According to this research study, 74 percent of adults used their phones to get directions or other location-based services. Sixty-five percent of smartphone users indicated that they had received turn-by-turn navigation or directions while driving from their phones, and 15 percent did so regularly. As of April 2012, the Pew survey found that 20 percent of mobile phone users had received real-time traffic or public transit information using their devices within the past 30 days. The increasing availability, capability, and affordability of ITS, GPS, wireless, and cloud technologies?coupled with the growth of data availability and data sharing?are causing people to increasingly use smartphone transportation apps to meet their mobility needs. New developments in contactless payment (such as nearfield communication, Bluetooth low energy, Visa payWave, and Apple Pay), in addition to a growing number of application programming interfaces (APIs) will facilitate a growth in "digital purses" and digital wallets (enabled through paperless and joint payment options), as well as multi-modal aggregators, trip planners, and booking systems. Additionally, the use of incentivization (e.g., offering points, discounts, or lotteries) and gamification (e.g., use of game design elements in a non-game context) are other key factors driving end-user growth of smartphone transportation applications. The increasing availability of real-time information (e.g., congestion, parking, and public transportation) will continue to impact both mobility choices and routing. Collectively, these tools are leading to the advent of "smart mobility consumers"- travelers who can combine information from multiple sources and make smarter, more informed travel decisions.emerging trend that may also alter non-work travel, particularly for non-discretionary trips. Telemedicine may reduce the need for some trips through tools, such as video conferencing of doctor visits with patients, e-transmission of diagnostic images, remote monitoring of patient vital signs, online continued medical education, nursing call centers, and web-based applications.

These technologies are coming at a time when the existing infrastructure is often at or beyond its capacity. Congestion, parking shortages, and frustration with existing for-hire vehicle services are causing travelers to search for innovative technologies and services to address these mobility challenges. Many of these technologies are being used both independently and in conjunction with ITS to achieve travel time savings (e.g., by using high occupancy vehicle lanes) and financial savings (e.g., by providing real-time information about low-cost transportation options).

Shared Mobility Service Options

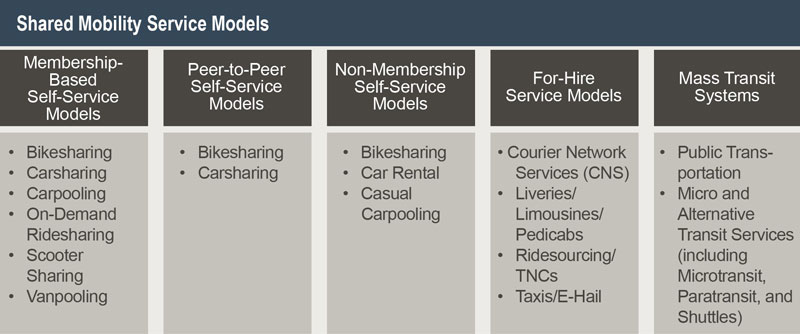

Shared mobility has become a ubiquitous part of the urban transportation network, encompassing a variety of modes ranging from public transportation, taxis, and shuttles to carsharing, bikesharing, and on-demand ride and delivery services. Fundamentally, these services can be categorized into five groupings: 1) membership-based self-service models, 2) P2P self-service models, 3) non-membership self-service models, 4) for-hire service models, and 5) mass transit systems. Some distinguish among the shared services between sequential (use by one user and then another, e.g., bikesharing and carsharing) and concurrent models (shared by many at one time, e.g., microtransit, carpooling, ridesplitting) (Transportation Research Board, 2015). This chapter synthesizes existing literature on the definitions and types of shared mobility services available, as of December 2015.

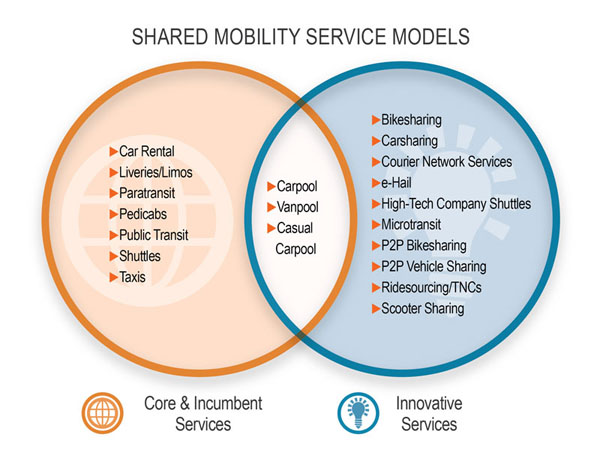

Shared mobility includes various service models and transportation modes to meet the diverse needs of users. This section shows incumbent and innovative services (Figure 1) and defines the five service models and the modes offered within each (Figure 2). Broadly, there are two ways to view shared mobility in the larger ecosystem of surface transportation modal options. Shared mobility can be viewed as emerging or innovative in contrast to existing core and incumbent services (see Figure 1). It can also be understood in the context of their underlying service models (see Figure 2). For example, shared mobility services may be membership-based, non-membership-based, P2P, or for-hire. Figure 1 and Figure 2 provide a list of incumbent and innovative services and a typology of these categories and their included modes, respectively.

FIGURE 1. Core, Incumbent, and Innovative Services

FIGURE 2. Shared Mobility Service Models

Membership-Based Self-Service Models

Membership-based self-service models contain five common characteristics: 1) an organized group of participants; 2) one or more shared vehicles, bicycles, scooters, or other low-speed mode; 3) either a decentralized network of pods or stations used for departure and arrival for roundtrip or station-based one-way services or a free-floating decentralized vehicle network with flexible departure and arrival locations typically within the confines of a fixed geographic boundary; 4) short-term access typically in increments of one hour or less; and 5) self-service access.

These models can include roundtrip services (motor vehicle, bicycle, or other low-speed mode is returned to its origin); one-way stationed-based (vehicle, bicycle, or low-speed mode is returned to different designated station location); and one-way free-floating (motor vehicle, bicycle, or low-speed mode can be returned anywhere within a geographic area). In addition to one-way and roundtrip service models, membership-based self-service models can be deployed as either "open systems" available to the public or "closed community systems" with limited access to predefined groups, such as members of a university community, residents of an apartment complex, or employees of a particular employer or office park. See descriptions of the range of innovative shared modes included in membership-based self-service models below.

|

Bikesharing

|

- IT-based public bikesharing first launched in North America in 2007 in Tulsa, OK. This was followed by the launch of SmartBike in Washington, DC, in 2008 and numerous other systems shortly thereafter throughout Canada and the United States. Bikesharing experienced near exponential growth in North America in 2011.

- Bikesharing users access bicycles on an as-needed basis. Trips can be point-to-point, roundtrip, or both, allowing the bikes to be used for one-way transport and for multimodal connectivity (first-and-last mile trips, many-mile trips, or both). Station-based bikesharing kiosks are typically unattended, concentrated in urban settings, and offer one-way station-based services (bicycles can be returned to any docking location). Free-floating bikesharing offers users the ability to check out a bicycle and return it to any location within a predefined geographic region. Bikesharing provides a variety of pickup and drop-off locations, enabling an on-demand, very low emission form of mobility.

- The majority of bikesharing operators cover the costs of bicycle maintenance, storage, and parking. Generally, trips of less than 30 minutes are included within the membership fees. Users can access bikesharing as members (e.g., typically on an annual, seasonal, or monthly basis) or as casual users (e.g., generally daily or per-trip basis). Bikesharing users can pick up a bike at any dock by using their credit card, membership card, key, and/or mobile phone (a new feature with BCycle and RideScout added in October 2015). They can return the bike to any dock (or the same dock in a roundtrip service) where there is room and end their session.

- In addition to the public bikesharing systems that are available to the public at large, closed-campus systems are increasingly being deployed at university and office campuses. These closed-campus systems are available only to the particular campus community they serve.

- In addition to these innovations, electric bikesharing (also known as e-bikesharing) is emerging. Electric bicycles (e-bikes) have an electric motor that reduces the effort required by the rider. Such bicycles can enable individuals to use the system who may otherwise have physical difficulties pedaling traditional bicycles or others who may be in dress clothing and want to avoid perspiring. E-bikes can also extend travel distances and enable bikesharing in areas of steep terrain and varied topography.

- In June 2015, the City of Seattle applied for a multi-million dollar grant to expand the city's Pronto bikesharing program to include some e-bikes. Similarly, in September 2015, Canadian-based Bewegen launched e-bikesharing in Birmingham, Alabama. The system includes an estimated 400 bikes and 100 e-bikes across 40 docking stations (Staff, 2015).

- A 2012 survey of 20 U.S. public bikesharing programs found the average cost of daily passes was $7.77, with all programs offering the first 30 minutes free of charge. Twelve programs offered monthly memberships, averaging $28.09 per month. Eighteen of the programs offered annual or seasonal memberships, costing an average of $62.46 (Shaheen S. , Martin, Chan, Cohen, & Pogodzinski, 2014).

|

|

Carsharing

|

- Carsharing launched in Canada in 1994, and this was followed by numerous programs throughout the United States starting in 1998. Individuals gain the benefits of private vehicle use without the costs and responsibilities of ownership.

- Individuals typically access vehicles by joining an organization that maintains a fleet of cars and light trucks deployed in lots located within neighborhoods, public transit stations, employment centers, and colleges/universities and sometimes also using on-street parking. Typically, the carsharing operator provides insurance, gasoline, parking, and maintenance. Generally, participants pay a fee each time they use a vehicle.

- Service models can include roundtrip carsharing (vehicle returned to its origin), one-way stationed-based (vehicle returned to different designated carsharing location), and one-way free-floating (vehicle returned anywhere within a geo-fenced area).

- A 2005 survey of American roundtrip carsharing operators found that the average cost to drive 50 miles for two hours in a carsharing vehicle was about $24, which rose to about $28 for four hours, $31 for six hours, and $34 for eight hours (Shaheen, Cohen, & Roberts, 2006).

|

|

Scooter Sharing

|

- As of September 2015, there were two scooter sharing systems in the United States: Scoot Networks in San Francisco, California and Scootaway in Columbia, South Carolina. Both of these systems offer one-way and roundtrip short-term scooter sharing, which includes insurance and helmets. Scootaway scooters run on gasoline, which is included within the price of the rental.

- Scooter users have two pricing options: 1) $4 per every half-hour of use with no monthly fee; or 2) $19 per month and usage billed at $2 per hour. Scoot has also recently introduced 10 four-wheeled, two-seater "Twizy" vehicles into its fleet from Renault (branded as Nissan in the U.S.), priced at $8 per half-hour of use (Scoot, unpublished data, 2015). Scootaway, located in South Carolina, bills at a flat rate of $3 per half-hour of use (Scootaway, unpublished data).

|

|

Vanpooling

|

- Vanpools are typically comprised of 7 to 15 people commuting on a regular basis using a van or similarly-sized vehicle. Vanpools normally have a coordinator and an alternative coordinator.

- Vanpool participants share the cost of the van and operating expenses and may share the responsibility of driving. A vanpool could cost between $100 and $300 per person per month, although this varies considerably depending on gas prices, local market conditions, and government subsidies (Martin, unpublished data).

|

Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Service Models

Carsharing and bikesharing have also given rise to peer-to-peer (P2P) systems that enable vehicle and bicycle owners to rent their vehicles and bicycles when they are not in use. In P2P service models, companies broker transactions among car, bicycle, or other mobility owners and renters by providing the organizational resources needed to make the exchange possible (i.e., online platform, customer support, driver and motor vehicle safety certification, auto insurance, and technology). P2P services differ from membership-based self-service carsharing or bikesharing in that the operator owns the private vehicles or bicycles being shared.

Similar to carsharing and bikesharing, P2P services also have their own niche markets. Spinlister (previously known as Liquid) is one P2P bicycle sharing system in North America. Another company, Bitlock, sells keyless Bluetooth bicycle locks that can be used for personal use or for P2P sharing. Getaround and Turo (formerly RelayRides) are examples of P2P carsharing operators providing service in metropolitan markets. Another service, FlightCar, provides vehicle owners with free parking at major airports in exchange for renting their vehicles to inbound visitors. In return, the vehicle owner receives a commission based on the number of miles the vehicle is driven.

As of January 2015, there were three common deployments of P2P mobility sharing: 1) P2P carsharing in urban neighborhoods (where privately owned vehicles are made available for carsharing in urban settings); 2) P2P airport-based carsharing (where outbound airport travelers can park and make their vehicles available for inbound airport passenger short-term rental); and 3) P2P bikesharing in urban neighborhoods (where privately-owned bicycles are made available for bikesharing use). There are four types of personal vehicle sharing ownership models: 1) Fractional Ownership Models; 2) Hybrid P2P-Traditional Models; 3) P2P Access Model (typically called P2P carsharing); and 4) P2P Marketplace.

|

Fractional Ownership

|

- Individuals sub-lease or subscribe to access a motor vehicle or low-speed mode owned by a third party. These individuals have "rights" to the shared service in exchange for taking on a portion of the expense. This could be facilitated through a dealership and a partnership with a carsharing operator, where the car is purchased and managed by the carsharing operator. This enables access to vehicles that individuals might otherwise be unable to afford (e.g., higher-end models) and results in income sharing when the vehicle is rented to non-owners.

- At present, fractional ownership companies in the United States include Curvy Road, Gotham Dream Cars, and CoachShare. In December 2014, Audi launched its "Audi Unite" fractional ownership model in Stockholm, Sweden. Audi Unite offers multi-party leases with pricing based on the model, yearly mileage (2,000 or 3,000 km or ~1,240 to 1,860 miles), and the number of drivers sharing the vehicle that ranges from two to five. For example, an Audi Unite A3 sedan can be leased among five drivers for approximately 1,800 kronors per month (~$208 USD per driver per month) for 2,000 annual km (~1,240 miles) on a 24-month lease. Each Audi Unite user is given a Bluetooth key fob and a smartphone app that allows co-owners to schedule vehicle use.

|

|

Hybrid Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Traditional Model

|

- Individuals access vehicles or low-speed modes by joining an organization that maintains its own fleet, but it also includes private autos or low-speed modes throughout a network of locations. Insurance is typically provided by the organization during the access period for both roundtrip carsharing and P2P vehicles.

- Members access vehicles or the other low-speed modes through a direct key exchange or a combination transfer from the owner or via operator-installed technology that enables "unattended access." Pricing in this model works similar to roundtrip carsharing.

- This model is frequently called P2P carsharing. It employs privately-owned vehicles or low-speed modes made temporarily available for shared use by an individual or members of a P2P company. Insurance is generally provided by the P2P organization during the access period. In exchange for providing the service, operators keep a portion of the usage fee.

- Members can access vehicles or low-speed modes through a direct key exchange or a combination transfer from the owner or via operator-installed technology that enables "unattended access."

- The P2P carsharing operator generally takes a portion of the rental amount in return for facilitating the exchange and providing third-party insurance. For example, Turo (formerly RelayRides) takes a 25 percent commission from the owner along with 10 percent from the renter. Getaround takes 40 percent from the owner for its services. With FlightCar, the car owner is paid $.05 to $.20 per mile, with an average payment of $20 to $30. There are no parking fees at the airport, and the vehicle is washed and vacuumed when the owner picks it up upon return. There also is a flat-rate monthly program in which the driver can net a total of $250 or greater.

- As of May 2015, there were eight active P2P operators in North America, with two more planned to start in the near future.

- P2P marketplace enables direct exchanges among individuals via the Internet. Terms are generally decided among parties of a transaction, and disputes are subject to private resolution.

|

Non-Membership Self-Service Models

Non-membership self-service models include rental cars and carpooling. See below for a description of these services.

| Bikesharing |

- As previously mentioned, users can access bikesharing as members (e.g., typically on an annual, seasonal, or monthly basis) or as casual users or non-members (e.g., generally daily or a per-trip basis). Casual users do not have bikesharing accounts, and typically the bikesharing operator does not retain information on casual users after billing for their usage is complete. As of the 2012 season, casual users accounted for 85.5 percent of all bikesharing users (Shaheen S. , Martin, Chan, Cohen, & Pogodzinski, 2014).

- A 2012 survey of 20 U.S. public bikesharing programs found the average cost for a daily pass was $7.77, and all the programs offered the first 30 minutes of riding free (Shaheen S. , Martin, Chan, Cohen, & Pogodzinski, 2014).

|

| Car Rental |

- This is a non-membership-based service or company that rents cars or light trucks typically by the day or week. Traditional rental car services include storefronts requiring an in-person transaction with a rental car attendant. However, rental cars are increasingly employing "virtual storefronts," allowing unattended vehicle access similar to carsharing.

- Historically, rental cars have focused on three different service models: 1) airport-based rental services located at air terminals (e.g., Hertz, Avis, National, and others); 2) neighborhood-based rental services (e.g., Enterprise); and 3) truck-based rental services (e.g., U-Haul, Ryder, and Penske).

- Car rentals are generally priced on a daily or weekly basis, often with differing rate structures for leisure and commercial use. In addition to base rental rates, most car rental companies offer ancillary and a la carte charges for a variety of products and services, such as car seat and GPS rentals and increased insurance coverage.

|

| Carpooling |

- This is a formal or informal arrangement where commuters share a vehicle for trips from either a common origin, destination, or both, reducing the number of vehicles on the road. Over the years, carpooling has expanded to include a number of other forms. Casual carpooling or "slugging" is a term used to describe informal carpooling among strangers, which has often been referred to as a hybrid between commuter carpooling and hitchhiking. With slugging, passengers generally line up in "slug lines" and are picked up by unfamiliar drivers who are commonly motivated to pick up passengers to take advantage of high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes, lower tolls, and similar benefits.

- In addition, the growth of the Internet and mobile technology has enabled online ridesharing marketplaces, such as Carma Carpooling, where users can arrange ad hoc rides typically on-demand or with minimal advance notice through a personal mobile device. Carpooling can include a small donation to the driver to reimburse costs (e.g., gas, tolls, parking), but it cannot result in financial gain without bringing about insurance and other regulatory challenges (Chan & Shaheen, 2011).

- Many public agencies distinguish carpooling from for-hire service models by permitting carpool passengers to reimburse carpool drivers up to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) standard mileage rate. In 2015, the IRS standard mileage rate was $0.57 per mile for business purposes, which is often used as a metric for suggesting carpooling cost sharing caps. Because the driver is not making a wage, carpool drivers are not required to carry commercial insurance coverage.

|

For-Hire Service Models

For-hire service models include pedicabs (a for-hire tricycle with a passenger compartment), ridesourcing, taxis, limousines, or liveries that carry passengers for a fare (either predetermined by distance or time traveled or dynamically priced based on a meter or similar technology). The fundamental basis of for-hire vehicle services involves a passenger hiring a driver for either a one-way or a roundtrip ride. For-hire vehicle services can be pre-arranged through a reservation or booked on-demand through street-hail, phone dispatch, or e-Hail using the Internet or a smartphone application. See below for a description of these models. For-hire service models include pedicabs (a for-hire tricycle with a passenger compartment), ridesourcing, taxis, limousines, or liveries that carry passengers for a fare (either predetermined by distance or time traveled or dynamically priced based on a meter or similar technology). The fundamental basis of for-hire vehicle services involves a passenger hiring a driver for either a one-way or a roundtrip ride. For-hire vehicle services can be pre-arranged through a reservation or booked on-demand through street-hail, phone dispatch, or e-Hail using the Internet or a smartphone application. See below for a description of these models.

| Courier Network Services (CNS) |

- CNS (also referred to as flexible goods delivery) provide for-hire delivery services for compensation using an online-enabled application or platform (such as a website or smartphone app) to connect delivery drivers using their personal vehicles with freight. These services can include: 1) P2P delivery services and 2) paired on-demand passenger ride and courier services.

- For example, Postmates and Instacart are two P2P delivery services. Postmates couriers operate on bikes, scooters, or cars delivering groceries, takeout, or goods from any restaurant or store in a city. Postmates charges a delivery fee in addition to a 9 percent service fee based on the cost of the goods being delivered. Instacart offers a similar service, but it is limited to grocery delivery and charges a delivery fee of between $4 and $10, depending on the time given to complete the delivery.

|

| Pedicabs |

- A pedicab is a for-hire service with a peddler that transports passengers on a cycle containing three or more wheels with a passenger compartment.

- Pedicab pricing can vary widely based on the pricing model and market served. For example, New York City Pedicab Company charges between $3 and $7, per minute, per pedicab (New York City Pedicab Company, 2015). In Charleston, Bike Taxi charges $5 per person per every 10 minutes (Bike Taxi, 2015).

|

| Ridesourcing |

- Ridesourcing services launched in San Francisco, CA, in the summer of 2012 and have rapidly spread across the United States and globe since then, meeting both support and resistance. They provide prearranged and on-demand transportation services for compensation, connecting drivers of personal vehicles with passengers. Smartphone mobile applications are used for booking, ratings (drivers and passengers), and electronic payment.

- In the San Francisco Bay area, uberX charges $3.20 as a base fare (including a "Safe Rides fee"), $0.26 per minute, and $1.30 per mile during non-surge times. In the same area, Lyft charges a base fare of $3.80 (including a "Trust and Safety fee"), $0.27 per minute, and $1.35 per mile. The prices mentioned are during non-peak times; prices usually go up during periods of high demand to incentivize more drivers to take ride requests (surge pricing).

- Recently, ridesourcing companies have released new apps that enable riders to share and split the costs of a fare (or what we call "ridesplitting"). Lyft Line and uberPOOL (launched [as beta] in August 2014) attempt to group passengers with coinciding routes into carpools. Recently, UberPOOL has been testing "Smart Routes," where users can get a discounted fare starting at $1 off the normal UberPOOL price in return for walking to a major arterial street, allowing drivers to make fewer turns and complete ride requests faster (de Looper, 2015). Furthermore, in November 2014, Lyft released Driver Destination, which enables drivers to pick up passengers along their personal trip routes, for instance, when they are traveling to and from work. This product can facilitate more carpooling, higher vehicle occupancies, and reduced travel costs and provide first-mile and last-mile connectivity to public transit along those routes.

|

| Taxis |

- This is a type of for-hire vehicle service with a driver used by a single passenger or multiple passengers. Taxi services may be either pre-arranged or on-demand. Taxis can be reserved or dispatched through street hailing, a phone operator, or an "e-Hail" Internet or phone application maintained either by the taxi company or a third-party provider.

- Since late-2014, there has been a rise in the application of e-Hail services in taxi fleets, particularly in major metropolitan areas using predominantly third-party dispatch apps, such as Flywheel and iTaxi. Increasingly, taxi and limousine regulatory agencies are developing e-Hail pilot programs and mandating e-Hail services.

- In late 2012, the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission approved an e-Hail pilot program permitting app developers to test their mobile taxi booking, dispatch, and payment systems in the city. In Washington, DC, the DC Taxicab Commission has mandated that all district taxicabs use the Universal DC TaxiApp. In Los Angeles, the Board of Taxicab Commissioners approved a mandate that required that the city's taxis use e-Hail mobile apps by August 20, 2015 or pay a $200 daily fine. Similar policies are under consideration in New York and Chicago.

|

| Limousines and Liveries |

- This is a limousine or luxury sedan offering pre-arranged transportation services driven by a for-hire driver or chauffeur.

- Similar to other for-hire vehicle service models, pricing for limousines and liveries can also vary widely. Generally, in most markets, these services are charged by the hour, starting around $50 per hour (and up). Additional service charges may apply.

|

Mass Transit Services

Mass transit systems include public transportation and alternative transit services. A description of these services is provided below. Mass transit systems include public transportation and alternative transit services. A description of these services is provided below.

| Public Transportation |

- Public transportation includes any mass transportation vehicle that charges set fares, operates on fixed routes, and is available to the public. Common public transportation systems include buses, subways, ferries, light and heavy rail, and high speed rail.

|

| Alternative Transit Services |

- Alternative transit services comprise a broad category encompassing shuttles (shared vehicles that connect passengers to public transit or employment centers), paratransit, and private sector transit solutions commonly referred to as microtransit. Shuttles can include classic first-and-last-mile connections between public transit and employment centers as well as high-tech company shuttles (often, but not necessarily, free to company employees and offering WiFi connection).

- Many alternative transit services can include fixed route or flexible route services, as well as fixed schedules or on-demand service. These services can include free shuttles (generally subsidized by transportation demand management agencies or private employers) and paid services, such as microtransit costs, which typically range between $3 and $7 per ride.

- In its most agile form (flexible routing, scheduling, or both), microtransit and paratransit can be bundled under the category "flexible transit services." Flexible transit services include one or more of the following characteristics: 1) route deviation (vehicles can deviate within a zone to serve demand-responsive requests); 2) point deviation (vehicles providing demand-responsive service serve a limited number of stops without a fixed route between spots); 3) demand-responsive connections (vehicles operate in a demand-responsive geographic zone with one or more fixed-route connections); 4) request stops (passengers can request unscheduled stops along a predefined route); 5) flexible-route segments (demand-responsive service is available within segments of a fixed route); and 6) zone route (vehicles operate in a demand-responsive mode along a route corridor with departure and arrival times at one or more end points) (Koffman, 2004).

|

References

Bike Taxi. (2015, December 7). Retrieved from Bike Taxi: http://www.biketaxi.net/

Chan, N., & Shaheen, S. (2011). Ridesharing in North America: Past, Present, and Future. Transport Reviews, 1-20.

de Looper, C. (2015, August 24). Uber Testing Bus-Like "Smart Routes. Retrieved from Tech Times: http://www.techtimes.com/articles/79084/20150824/uber-testing-bus-smart-routes.htm

Koffman, D. (2004). TCRP Synthesis 53: Operational Experiences with Flexible Transit Services. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board of the National Academies

McClatchy Tribune Services. (2013, September 10). Part-time job growth rapidly outpacing full-time opportunities, statistics show. Retrieved from The Times-Picayune: http://www.nola.com/business/index.ssf/2013/09/part-time_job_growth_rapidly_o.html

NYC Pedicab Co. (2016, March 7). Central Park Pedicab Tours FAQs. Retrieved from NYC Pedicab Co.: http://www.centralparkpedicabs.com/p/faqs.html

Packaged Facts. (2015, September 21). Packaged Facts: 30% of U.S. Consumers Order Online for Same Day Delivery. Retrieved from PRN Newswire: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/packaged-facts-30-of-us-consumers-order-online-for-same-day-delivery-300145756.html

Pew Research Center. (2014, October). Mobile Technology Fact Sheet. Retrieved from Pew Research Center: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/mobile-technology-fact-sheet/

Shaheen, S. A., Cohen, A. P., & Roberts, J. D. (2006). Carsharing in North America: Market Growth, Current Developments, and Future Potential. In Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board (pp. 116-124). Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board of the National Academies.

Shaheen, S., Martin, E., Chan, N., Cohen, A., & Pogodzinski, M. (2014). Public Bikesharing in North America During A Period of Rapid Expansion: Understanding Business Models, Industry Trends and User Impacts. San Jose: Mineta Transportation Institute.

Staff, B. (2015, April 20). Birmingham, Alabama, planning e-bike share system. Retrieved from Bicycle Retailer: http://www.bicycleretailer.com/north-america/2015/04/20/birmingham-alabama-planning-e-bike-share-system#.VdTpWJedpn0

Transportation Research Board. (2015). Between Public and Private Mobility Examining the Rise of Technology-Enabled Transportation Services. Retrieved from the Transportation Research Board: http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/sr/sr319.pdf

|