1. Introduction to Desk ReferenceTravel Demand Management (TDM) has been included in many transportation plans over the past three decades as a means to address key policy objectives, including: energy conservation, environmental protection, and congestion reduction. For the purpose of this desk reference, TDM is synonymous and used interchangeably with the terms "Transportation Demand Management" or simply "demand management," and is defined a set of strategies aimed at maximizing traveler choices. Many recent transportation plans appropriately place TDM very high in policy-level discussions. TDM is seen as a vital part of an approach to plan, design, and operate "smarter" and "more efficient" transportation systems in a region. For example, the Washington State Department of Transportation (DOT) plan for fighting congestion, Moving Washington, includes managing demand as one of three equal pillars of their approach.

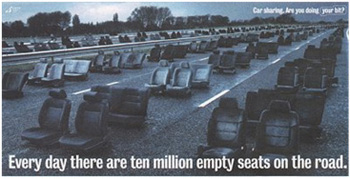

In addition to policy objectives, TDM strategies are usually listed within the set of projects that are found toward the end of most transportation plans or as part of the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP). Here, in many of the transportation plans, these projects are often concentrated on traditional commuter ridesharing concepts, such as the funding of ridesharing programs, vanpool subsidies, or telecommuting assistance, which primarily strive toward long-term trip reductions for air quality goals. However, the broader concept of demand management often gets lost in the middle, between high-level policy statements at the beginning of the planning process and specific projects that conclude most plans. In the heart of most transportation plans, TDM is not viewed as a vital, day-to-day operational philosophy on how to manage and operate a transportation system to address a wide variety of transportation issues such as mobility, accessibility, land-use, and livability. While traditional TDM strategies such as ridesharing, vanpool, and telecommuting programs are still vital and serve large sections of the population, new opportunities to manage travel demand have emerged in recent years with the advent of technology (and more importantly connectivity) to the transportation arena. Personal technology and communication advances show promise in making personal travel decisions more dynamic and fluid. In parallel, transportation systems management is progressing toward a more "active" management of the system, recognizing the role of influencing the traveler early in the trip making process on a day-to-day basis. Together, these developments create new opportunities for demand management. In fact, currently, our day-to-day efforts to manage and operate the transportation system are all about managing demand, since we cannot expand capacity in the very short run. For example, advanced traveler information is fundamentally a demand management strategy to help travelers learn of bottlenecks, slowdowns, and incidents so that they might avoid them by traveling a different route or at a different time. Acknowledging that most of what we do to operate our transportation system today is demand management goes a long way toward understanding the need to better integrate TDM into the transportation planning process. Many federal, state, and local initiatives are seeking to better integrate TDM into transportation projects and overall solutions to congestion, environmental and energy concerns, and livability issues. For example, the U.S. DOT is supporting the concept of Integrated Corridor Management (ICM), which includes mode shift as a primary measure of improving the efficiency and person throughput of congested corridors.1 The premise of ICM is that transportation corridors often contain unused capacity in the form of parallel routes, the non-peak direction on freeways and arterials, single-occupant vehicles, and transit services that could be managed through information to the travelers to help reduce congestion. By "load balancing" across facilities and managing the corridor as an asset, travel times and travel time reliability are improved (or maintained) for the individual traveler while the overall corridor throughput increases. Early deployments and demonstrations in Dallas and San Diego provide real-world case studies of demand management at a corridor level.  Source: DfT and the Highway Agency Another major DOT program that highlights the role of demand management is the Urban Partnership Agreements/Congestion Reduction Demonstration Program. Demand management through pricing, traditional TDM, and transit improvements are three of the four pillars of this program. Cities involved in the program include Seattle, Minneapolis, Miami, Atlanta, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Each of the cities is implementing a package of solutions aimed at managing demand across key facilities in their region. Similarly, TDM planning processes around the country are evolving as well. New approaches to planning for operations try to move away from "project-based" decision making to focus on "outcomes-based" planning. Under this approach, regional performance outcomes—operations objectives—are developed. Planning and investment decisions are made utilizing performance measures, and relying on data to determine the most effective strategies for meeting operations objectives. A performance-based, objectives-driven approach to planning for operations is based on the concept that "what gets measured gets managed." Investments are made with a focus on their contribution to meeting regionally agreed-upon objectives. By implementing this approach, resources are allocated more effectively to meet performance objectives, resulting in improved transportation system performance. With these programs and others, demand management is clearly evolving to encompass policy objectives other than just air quality conformity, including congestion, livability, and even goods movement. It is important that TDM be considered early, often, and effectively in the planning process. This document has been developed to serve as a desk reference on integrating this new, broader vision of TDM into the transportation planning process. The purpose of the desk reference is to provide the reader with a better understanding of where, how, and when to integrate TDM into the evolving performance-based transportation planning process. The importance of the planning process in helping provide a clear vision, goals and objectives, approach, and funding for demand management (as well as other transportation improvements) cannot be overstated. As such, this report complements and supports several other important Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) guidance documents on the transportation planning process, including guidance that discusses the role of TDM in the planning process. Table 1.1 provides bibliographic information on each FHWA reference. The web address for each report can be found at the end of this chapter. These documents provide guidance on how the planning process can be adapted for operations using an objective-driven approach at state and metropolitan levels.

While this report provides ample examples and illustrations, and discusses the known effectiveness of TDM strategies, the desk reference is not intended as a technical resource on TDM effectiveness or implementation for a given strategy or set of strategies. The desk reference does point the user to other resources and reports that are better suited to that purpose. Key resources are provided at the end of each section. 1.1 Organization of the Desk ReferenceThe desk reference is fundamentally organized around two aspects of transportation planning - policy objectives and scope of the planning effort. The report discusses how TDM relates to seven key policy objectives that are often included in transportation plans, such as congestion and air quality. It then discusses how TDM might be integrated into four levels of transportation planning from the state down to the local level. Acknowledging that readers will have differing levels of experience and skills when it comes to TDM and the planning process, the desk reference includes discussion of various levels of capabilities to help the reader determine the most targeted guidance for their situation. The report also includes information on tools available for evaluating TDM measures and on the known effectiveness of these measures. Figure 1.1 provides a cross-walk of the major sections in the document.

Figure 1.1: Desk Reference Structure Integration into the planning process implies consideration of TDM at various steps starting with the highest level of strategy and visioning to more specific goal setting all the way to the incorporation into specific plans and conducting performance evaluations. It is important to recognize that agencies are currently integrating TDM to the best of their abilities in their plans. The organization and the content of the desk reference are driven by the principle that there is no "one size fits all" solution to integrating TDM. In essence, integrating TDM into the planning process is about capability maturity across the various planning activities that occur at an agency. Leveraging existing research into the capability maturity model developed for The American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO),2 the desk reference strives to provide agencies a model to self-identify/assess their capability and identify the desired actions to improve their processes. The premise behind the model is that any process goes through evolutions as it is improved. By utilizing the same model and the same assessment approach, organizations can benchmark how their process rates against their peers and identify specific steps that they can take to move along the capability continuum. For each of the planning levels, three levels of capability are identified:

Figure 1.2: Capability Levels and Actions Inform the Structure of the Desk Reference Topically, this desk reference is organized as follows:

The desk reference includes examples, case studies, and best practices to support the information in each section. These are presented in colored text boxes throughout the reference. Selected resources are also identified at the end of each section. 1.2 Use of the Desk ReferenceThe intended users of this desk reference are transportation planning professionals who are seeking information on the role of TDM in meeting specific needs they face in their planning efforts. Users can pick and choose the sections that are most related to their issue at hand (see Table 1.2 below). The report was purposely organized in a manner that would allow for this targeted use. This does imply a certain degree of repetition of terms and references in each section. Table 1.2 provides some directions on use of this document.

1 USDOT/RITA, Joint ITS Program Office, Integrated Corridor Management, http://www.its.dot.gov/icms/index.htm. PDF files can be viewed with the Acrobat® Reader®. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||