Measuring Border Delay and Crossing Times at the U.S.–Mexico Border—Part II

Guidebook for Analysis and Dissemination of Border Crossing Time and Wait Time Data

Final Report

(You will need the Adobe Acrobat Reader to view the PDFs on this page.)

INFORMATION DISSEMINATION

Key Steps for Data Dissemination

Traveler information can be disseminated using different mechanisms, which include agency Web sites, DMSs, and highway advisory radio (HAR). One scenario is that the implementing agency may have capabilities to relay traveler information through a majority of sources including field devices. Another scenario is that the implementing agency is only responsible for its RFID-based border crossing time and wait time measurement system and has to share the traveler information generated by the system with other agencies that are responsible for field devices and local media. In the second scenario, the implementing agency needs to be able to share the traveler information data using an open and non-proprietary format so that other agencies can pull the information easily.

For implementing traveler information, the following are some key questions that need to be answered:

- What is the format of the information?

- Does it need to follow industry standards?

- What is the content of the information?

- How often is the information updated?

The implementing agency also needs to put forward policies and procedures prior to relaying information through the field devices and Web sites. Such policies and procedures may cover when and how to relay the information, accuracy of the information, scope, and third-party use of the data. While implementing traveler information at the border, agencies also need to be cognizant of requirements to be compliant with the American with Disabilities Act (ADA), multilingual needs, and limited English proficient callers (especially for 511).

Careful consideration needs to be given to policies and procedures for dissemination of data to ensure stakeholders are aware of data generated and have maximum opportunities to share it.

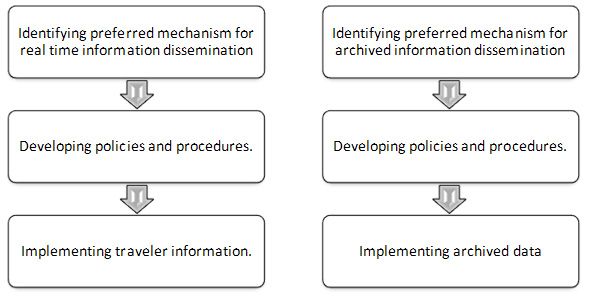

Figure 13 illustrates the key steps for disseminating real-time and archived data. These steps include identifying preferred mechanisms, developing policies and procedures, and implementing the information dissemination.

Disseminating Traveler Information

There are two broad categories by which traveler information can be relayed to users—(a) intelligent transportation system (ITS) methods such as DMS, HAR, and 511 systems, and (b) non-ITS methods such as local media and social networking sites. Traveler information provides freight carriers with capabilities to schedule and to choose between border crossings, where possible, to reduce their overall trip time. Each relay mechanism has its inherent strengths and capabilities, and while deciding which mechanism to choose from, the implementing agency needs to clearly outline strengths and capabilities of each mechanism and also resources needed. Under CBP’s Automated Commercial Environment (ACE) Program, submission of an e-manifest to CBP includes the port code where the truck is meant to cross. There are certain regions such as El Paso and Laredo where there are multiple crossings within a port code that can be accessed on the same port code, but otherwise the e-manifest must be updated if the truck is diverted to a different crossing. Traveler information can be used for scheduling as well. Providing traveler information on the U.S.–Mexico border could be a joint effort between agencies on both sides of the border. Hence, it is strongly recommended that the data exchange and information display formats (including bilingual requirement) be consistent on both sides of the border so that the freight carriers do not get confused by the messages relayed.

Identifying Preferred Mechanisms

The implementing agency needs to seek stakeholder feedback for identifying preferred mechanisms to relay traveler information. This needs to be based on goals and objectives of the system for providing such information, cost and resource constraints, and technology preference. Table 3 describes advantages and disadvantages of currently available mechanisms to relay border-related traveler information.

At a minimum, the implementing agency needs to provide an RSS feed to relay current (and predicted) crossing and wait times at the border. If an implementing agency does not have resources to deploy field devices such as DMSs or HAR, then at least it can provide a medium to share the data with other agencies. In this way, the systems have potential to integrate with existing field devices based on coordination and approval of the devices’ owners (e.g., MPO, city, State). Because an RSS feed uses open and non-proprietary extensible markup language (XML) format, external agencies, private entities, local media, and mobile application developers can obtain the information as soon as the information is updated in the feed.

| Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| RSS Feed |

|

|

| Agency Web Sites |

|

|

| Dynamic Message Signs |

|

|

| Social Networking Sites (SNSs) |

|

|

| Mobile Devices |

|

|

| In-Vehicle Navigation Devices |

|

|

| 511 Systems |

|

|

| Highway Advisory Radio |

|

|

| Local Media and Kiosks |

|

|

Developing Policies and Procedures

An implementing agency relaying/sharing crossing and wait time information needs to clearly define policies and procedures for other agencies to use shared data as traveler information. The implementing agency needs to enter into agreements with the agencies wanting to share the data. The agreement needs to describe medium of data-sharing protocol (e.g., RSS, hypertext transfer protocol [HTTP]), time of data availability, and update frequency. Two agencies agreeing to share the data need to agree on how each agency plans to use the data. An example of a TxDOT agreement for sharing ITS data is included as the Appendix. Another example, the New York City Department of Transportation’s (DOT’s) Video and Traffic Flow Data Sharing Agreement, can be accessed at http://a841-dotweb01.nyc.gov/datafeeds/video-partnership-agreement.pdf.

Numerous private entities provide traffic information to in-vehicle navigation and route guidance systems. The implementing agency needs to explore the possibilities of selling and/or bartering border crossing and wait time information with private companies for mutual benefit.

Implementing Traveler Information

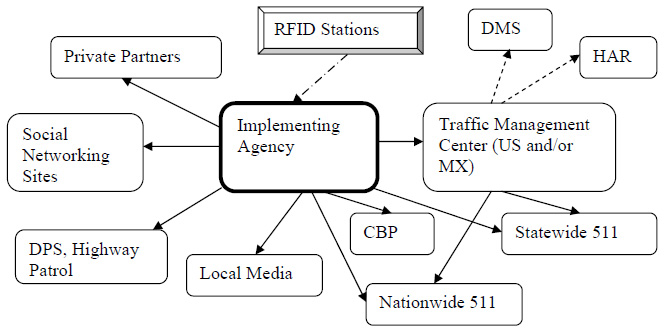

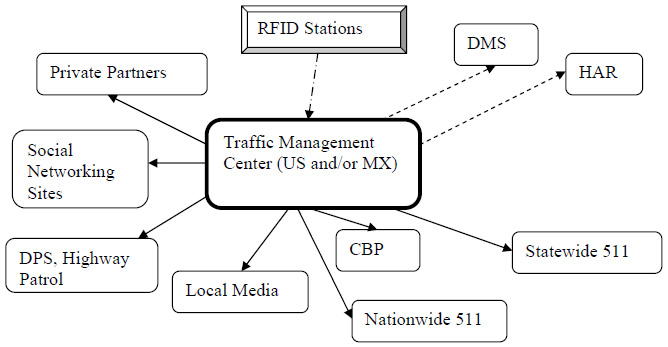

An implementing agency can relay border-related traveler information using various ITS and non-ITS mechanisms. There are two possible scenarios. The first scenario is that the implementing agency has capabilities to relay traveler information through multiple sources including field ITS devices such as DMSs and HARs through its transportation management center (TMC). RFID stations need to be directly connected to the TMCs. Agencies such as State DOTs and multiagency consortia operate and maintain a wide variety of field ITS devices through a TMC and already have the necessary infrastructure in place to relay border-related information, which then essentially becomes just added information.

Another scenario is that the implementing organization does not operate and maintain ITS field devices. These could be an MPO, private company, city agency, or non-profit agency. Hence, the implementing organization has to share the traveler information generated by the RFID-based border crossing time and wait time measurement system with other agencies (e.g., State DOTs) that operate and maintain field ITS devices. In this case, the implementing agency needs to be able to share the traveler information data using an open and non-proprietary format so that other agencies can pull the information easily.

Both implementation scenarios are illustrated in Figure 14.

| RSS feed via Internet | |

| Optical fiber or wireless | |

| Cellular modem |

RSS Feeds

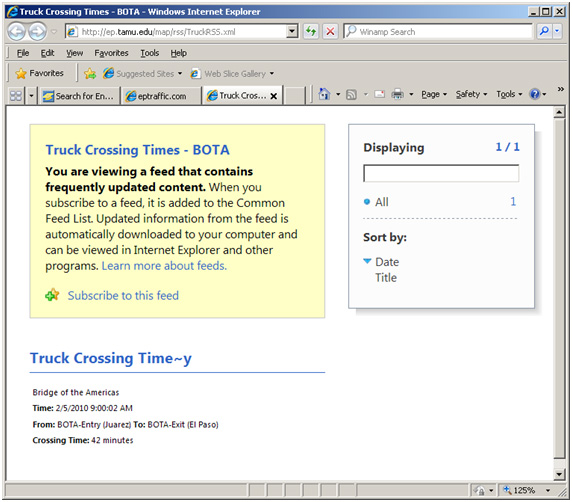

RSS has proven to be an extremely cost-effective method to share near-real-time data with external agencies, motorists, local media, and TMCs. RSS includes a standardized XML file format containing information to be published once and viewed by many different programs.

The RSS reader checks the user’s subscribed feeds regularly for new work, downloads any updates that it finds, and provides a user interface to monitor and read the feeds. RSS formats are specified using XML, a generic specification for the creation of data formats. RSS feeds can be read using software called an RSS reader, feed reader, or aggregator, or even the latest versions of commercially available Web browsers, which can be Web-based, desktop-based, or mobile-device-based.

A snapshot of an RSS feed developed to relay most recent truck crossing times at BOTA and Pharr is shown in Figure 15. The user subscribes to a feed by entering into the reader the feed’s URL or by clicking an RSS icon in a Web browser that initiates the subscription process.

Agency Web Sites

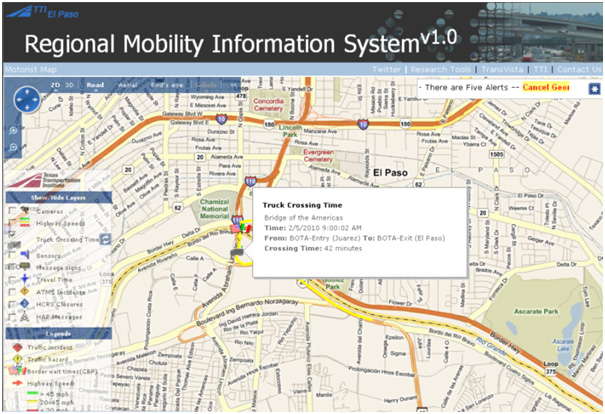

Agency Web sites can either pull information from the RSS feed or directly from a database that is part of the RFID-based border crossing time and wait time measurement system and show the crossing and wait time information in graphical, text, and map-based formats. Figure 16 shows a snapshot of a Web site that reads the RSS feed from the RFID-based border crossing time and wait time measurement system deployed at BOTA. The truck crossing time from the RSS feed is shown on the map-based Web site using color-coded line segments as well as in a text. The text format of the information also includes when the information was computed and relayed, thus providing an indication of the data timeliness. RSS feed provides only the data, while the users (data consumers and external agencies) need to design and display the data in an appropriate format.

For colorblind users, Web site displays like the one shown above can be modified using icons instead of color-coded segments. The color of the icons change based on the current value of average crossing time, and the icons could use monotone color schemes such as black, dark grey, and light grey instead of red, yellow, and green.

Dynamic Message Signs

DMSs are typically operated and maintained by organizations such as State DOTs (Federal in the case of Mexico) and multiagency consortia. For northbound traffic, DMSs can be located on the Mexico side of the border, which means Secretaria de Comunicaciones y Transportes (SCT) or some other Mexican governing body needs to develop policies and procedures to display border crossing and wait times via DMSs. State agencies in the United States usually follow internally developed operating guidelines to display messages by DMS and typically comply with the Manual for Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD). FHWA has no specific policy or position on travel time messages on DMSs but encourages following the MUTCD and has encouraged each State to develop its own standard.[3]

Some of the key items regarding display of border crossing and wait time have been derived from the best practices for displaying highway travel times on DMSs and are as follows:

- Information displayed over DMSs adds significant value during special events and incidents.[3]

- Before crossing and wait times are implemented over DMSs, raise public awareness using a message such as “Crossing time and wait time coming in X days.”

- If possible, information needs to be displayed on DMSs without the need for manual input from TMC operators.

- To save power, information can be posted during peak hours and special events only.

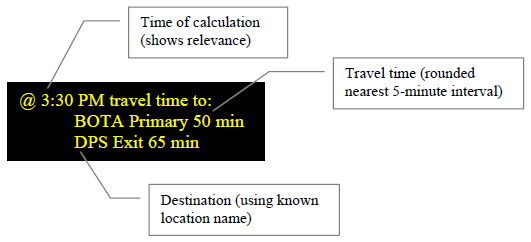

- While displaying information over DMSs, also report time of calculation (i.e., @ 4:30 PM).[4]

A recommended format for displaying multiline messages over DMSs is shown in Figure 17.

Social Networking Sites

SNSs are Web-based services that allow individuals to (a) construct a public or semipublic profile within a bounded system, (b) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (c) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system. Examples of these sites include Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and FourSquare. These Web sites are popular among the younger population, who favor the Internet over traditional forms of media such as television, radio, and newspapers for news and information. However, they are becoming increasingly popular among all users of the Internet. Government agencies, including several other State transportation departments, are using new media such as SNSs to enhance their efforts to provide information to the public.

These sites function differently than standard Web pages and feature the consolidation of different information sources onto one page, often with information pushed to them. The sites generally require individuals to register and select sources they wish to follow, with updates flowing to their social networking pages automatically.

The implementing agency wanting to publish the traveler information on its SNS page/account needs to develop a process that involves using the SNS-provided application programming interface (API) to read data from a source at the user’s end. This source could be an RSS feed or a database. The application that encapsulates the API then writes messages to its SNS page/account automatically at predefined intervals.

Mobile Applications

Dissemination of border-related traveler information through mobile devices can be implemented in various ways. The implementing agency can develop a mobile version of the agency Web site that shows current and predicted crossing and wait times in a simplified text format without the use of maps and graphics. The implementing agency can also develop a mobile-operating-system-specific application that pulls RSS information from the agency source and displays the information on the phone.

However, the implementing agency has to make a policy decision regarding promotion of mobile use while driving, since driver distraction due to use of cell phones or other electronic devices is a growing safety concern. In light of distracted driver concerns and laws, maximum use needs to be made of hands-free/eyes-free voice applications. For example, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission has launched a new iPhone and Droid application called TRIP Talk that reads audio alerts to travelers when there is a closure or delay ahead. The application senses the driver’s position and direction on the Turnpike and talks to the driver when it detects trouble spots nearby. Unlike other travel-alert tools, TRIP Talk is hands-free and eyes-free.[5] If an external agency comes forward to develop applications to relay border-related information via mobile devices and requests data from the implementing agency, then it needs to clearly state its policy regarding distribution of such data for mobile use.

In-Vehicle Navigation Devices

An in-vehicle global positioning system (GPS)-based navigation device is essentially either an in-built or an external device that provides real-time route guidance to the motorist. Commonly available navigation devices can provide information on impending traffic conditions such as location of incidents, congestions, travel time to destination, and alternate routes. Navigation devices are fed traffic information supplied by third-party information providers that collect traffic data from multiple sources.

Freight carriers can benefit from the use of navigation devices that can also provide border-related information and door-to-door travel time including crossing and wait times at the border. During a vehicle’s trip, recipients of disseminated messages need to consider distracted driver laws in effect.

The implementing agency needs to enter into a data-sharing/selling agreement with interested private entities that provide traffic information to navigation device manufacturers. The revenue can then be used to operate and maintain the RFID-based border crossing time and wait time measurement system.

511 Systems

Telephone services for travelers provide real-time information about work zones, traffic incidents, and other causes of congestion. They allow travelers to make more informed decisions about their travel routes or modes and increase safety by helping motorists avoid areas with congestion or incidents. The U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) petitioned the Federal Communications Commission in 1999 for a three-digit dialing code for travel information and was assigned 511 in 2000. Before the 511 dialing code was assigned for travel information, more than 300 different telephone numbers provided travel information in the United States. Nearly 156 million Americans, or almost 54 percent, now have access to 511 services.[6] Phone users who are hearing impaired can call 711, the national three-digit number for access to the Telecommunication Relay Services (TRS), to access 511 hearing-impaired services.

In the United States, the 511 Deployment Coalition offers 511 implementers technical advice on how to deal with callers who logically want information on transportation facilities and services outside of the area served by the local 511 system.

Mexico is deploying a nationwide system similar to 511 systems that will provide, among other services, border-related traveler information on the U.S.–Mexico border. Except for the State of Texas, all the other States on the U.S.–Mexico border have a regional or statewide 511 system.

There are two broader issues regarding relaying cross-border-related traveler information via 511 systems:

- Mexican and U.S. State 511 systems have to establish a coordination mechanism to make sure the traveler information is provided consistently to cross-border travelers. For example, travelers might be confused if the Mexican 511 system and U.S. system relay different or conflicting crossing and/or wait times for the same border crossing. This confusion can be prevented if both systems use the same data source for the border-crossing-related traveler information.

- Messages relayed by the U.S.-based 511 systems are required by law to be compliant with the ADA, multilingual needs, and limited English proficient callers [6] .

Border-crossing-related traveler information can be shared with 511 implementers using RSS feeds from the RFID-based border crossing time and wait time measurement system implementing agency. The 511 implementer then reformats the data to convert them into digital voice recordings. While providing border-related traveler information through a 511 system, callers need to be given a main menu option to say Border Crossings and then choose a specific border crossing from the menu. Most 511 systems have Web access, and online users need to be given a choice regarding which POE is of interest and that POE’s crossing and wait times. If there is crossing and wait time information available for different modes (e.g., commercial trucks, passenger vehicles) and program types (e.g., FAST, documented commuter lane [DCL]), then crossing and wait times for these specific types and modes need to be relayed. Stakeholders need to be able to recommend specific content of the message during pre-deployment studies.

Highway Advisory Radio

HAR is another means of providing travelers with information in their vehicles. Traditionally, information is relayed to highway users through the AM radio receiver in their vehicles. Upstream of the HAR signal, users are instructed via roadside or overhead signs to tune their vehicle radios to a specific frequency. Usually, the information is relayed to the users by a prerecorded message, although live messages can also be broadcast. HAR is an effective tool for providing timely traffic and travel condition information to the public.

Messages are broadcast in the field from transmitters that play stored messages. Newer HAR systems allow text-to-speech conversions. Hence, TMC operators can type in the text message or load stored text templates and modify the sentence. The text is automatically converted to digital voice and transmitted via HAR stations.

Typically, HAR stations are managed by central software within a TMC. There are no prevailing standards as to how the traveler information message needs to be relayed over HAR stations. Hence, State DOTs and TMCs develop their own operating guidelines. A typical message format includes:

- An introductory statement (agency name, location of HAR, date, and time).

- An attention statement (to address a certain group of motorists or destination).

- A problem statement.

- A location statement.

- An effect statement (e.g., lane closure, delay)..

- An action statement.

A sample message for relaying border-crossing-related traveler information through HAR could be:

ATTENTION TRUCKS TRAVELING SOUTHBOUND TO MEXICO

MAJOR DELAYS TO ENTER MEXICO THROUGH BOTA

VIA SOUTHBOUND US54 AND EASTBOUND IH10

WAIT TIME EXCEEDING TWO HOURS

USE ZARAGOZA PORT OF ENTRY

Local Media and Kiosks

Local media include radio stations and television stations that are known to relay traffic information. Local media at border cities already provide wait time information and POE closure information as part of their news broadcasts. Many radio and television stations also maintain their own Web sites that show border wait time information. An RFID-based border crossing time and wait time measurement system implementing agency needs to coordinate with local media to share crossing and wait time data, since local media is the most pervasive mechanism to relay traveler information. Studies have shown that local media still remains the number one source of traveler information for motorists. The implementing agency can provide an RSS feed to local radio and television stations, which can then use the feed as a source to relay border crossing and wait times.

Many States and cities have also deployed kiosks or video terminals at tourist information centers, airports, truck parking areas, and transit terminals. Border crossing information can be easily implemented on these kiosks. Another innovative idea is to collaborate with banks to provide traveler information on their automatic teller machines (ATMs) to take advantage of their larger deployment.

Disseminating Archived Data to Stakeholders

Archived border crossing and wait time data has broad applications for planners, decision-makers, engineers, researchers, and the trade community. Archived data presented in the form of different combinations of performance measures, described in chapters 2 and 3, are valuable in decision-making, border crossing performance comparisons, infrastructure improvements, and air quality studies.

Archived data can be released to stakeholders by using Web-based, pre-coded, interactive charts and graphs. However, in the presence of more than one source of archived data (i.e., maintained by multiple agencies), formalized data-sharing mechanisms between archives maintained by agencies in the United States and Mexico are highly desirable. To achieve an efficient data-sharing mechanism, each agency needs to maintain its metadata (e.g., time and date of creation, scope, data quality) and other data catalogues.

However, to bring all the agencies together and agree on mechanisms to share archived data is both complex and resource intensive. All agencies need to agree on such topics as the release of metadata to each other, metadata conventions, and standard data dictionaries. Hence, agencies need to agree on using industry standards for metadata and data dictionaries to reduce cost and increase efficiency of interagency access to archived data. Consortia or groups such as the United States–Mexico Joint Working Committee (JWC) and the United States–Canada Transportation Border Working Group (TBWG) can certainly play a crucial role in laying a framework for achieving interagency archived data-sharing mechanisms.

Other key considerations for disseminating archived data are necessary policies and procedures, especially for releasing large blocks of raw data, compliance with ADA, and bilingual user requirements.

Identifying Preferred Mechanisms

Unlike with traveler information, mechanisms to disseminate archived data are limited. Each mechanism has strengths and capabilities and costs associated with it. The decision to implement one or more dissemination mechanisms depends on what kind of users the archived data are being delivered to. There are two distinct categories of archived data users—regular users and power users.

Regular users typically require high-level summary charts and graphs and dashboards. They are decision makers, policymakers, and high-level planners—possibly members of the public. They have no need to perform complex data analysis on the archived data.

Power users, on the other hand, perform analysis beyond what is typically performed by regular users. They are planners, engineers, statisticians, modelers, and researchers and need to perform functions such as complex data analysis and data mining. They often require blocks of raw and aggregated data for their specific needs.

The implementing agency also needs to be cognizant of requirements for ADA compliance and bilingual users. Fortunately, most software applications provide multilingual support, meaning charts, graphs, and Web contents can be easily duplicated and implemented in a different language.

The implementing agency needs to seek stakeholder feedback for identifying preferred mechanisms to disseminate archived data. This needs to be based on factors such as goals and objectives of providing such information and cost and resource constraints. Table 4 describes advantages and disadvantages of available mechanisms to disseminate archived data to stakeholders.

| Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

Web Site Consisting of Pre-Coded Charts and Graphs |

|

|

| External Storage Devices |

|

|

Printed Reports and Summaries |

|

|

Developing Policies and Procedures

An implementing agency relaying/sharing crossing and wait time information needs to clearly define policies and procedures for other agencies to use the traveler information. An implementing agency needs to enter into agreements with other agencies wanting to share the data. The agreement needs to describe details such as medium of data-sharing protocol (e.g., RSS, HTTP), time of data availability, and update frequency.

Implementing Archived Data

Web Sites

Providing archived data via Web sites in the form of predefined performance metrics formatted into pre-coded interactive charts and graphs is perhaps the most common mechanism of disseminating archived data. One of the key requirements to accomplish this is storing the archived data in a highly structured relational database.

Also, complying with ADA requirements and providing the content in multiple languages needs to be considered, given the fact that stakeholders come from bordering countries with two different languages in common use at each border. Fortunately, newer Web content development applications have capabilities to change the language without much effort.

The content of the Web site and presentation of pre-coded charts and graphs can be obtained from the stakeholder input, and some of the groundwork is typically done during the design phase.

The content of the Web site needs to be designed based on which categories of users it serves. Regular users typically require high-level summary charts and graphs and dashboards. Simple but interactive charts and graphs of performance measures suffice for their needs. They have no need to perform complex data analysis on the archived data.

Power users, on the other hand, perform analysis beyond what is typically performed by the regular users. They need to perform complex data analysis or data mining, and they often require blocks of raw and aggregated data for their specific needs. Hence, they often resort to downloading blocks of raw data and performing the analysis offline. Another option is to provide a business intelligence platform (or middleware) that connects directly to the database and the data warehouse and performs complex analysis using functions provided by the middleware. This allows multiple power users to create and save charts and graphs to suit their individual and/or agency needs.

Mobile devices with fully capable Web browsers can also be used to access interactive charts and graphs. As an alternative, a mobile-device-compatible Web site can be created with appropriately sized charts and graphs.

External Storage Devices

Stakeholders may request blocks of raw and/or aggregated data via external storage devices such as CD-ROMs and external hard drives. Typically, implementing agencies can either provide flat files (e.g., comma-separated values [CSV], spreadsheet) or blocks of data stored in flat files without any problem. It is also efficient to maintain a file transfer protocol (FTP) site whereby users with valid credentials (username and password) can download the data with Internet access.

Agencies also have options to use virtual or online storage sites where flat files can be stored for users to download. That way, implementing agencies do not have to maintain an FTP site, and stakeholders can simply download the data from virtual storage sites.

Published Reports and Summaries

Publications in the form of semiannual and annual reports on the state of the border crossings are also an effective way of communicating with stakeholders. These reports needs to contain three key items—overall border crossing trends on the international border, border crossing and district performance comparisons, and individual border crossing performances. Two illustrative examples in circulation are the Border Barometer, which is published by the Border Policy Research Institute (BPRI) and the University of Buffalo (UB) for the U.S.–Canada border, and Northern Traffic Trends, published by the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI) for the U.S.–Mexico border. Border Barometer (available at http://www.regional-institute.buffalo.edu) is a tool that provides a U.S. perspective on northern border performance, and Northbound Freight Trends (available at http://tti.tamu.edu) provides a U.S. perspective on southern border performance. Both reports seek to provide researchers, policymakers, and other interested parties with a better understanding of economic conditions and trends along the entire border and at individual ports of entry. A snapshot of both reports is shown in Figure 18.

Neither of the reports includes crossing-time-related performance measures yet. However, with deployment of several crossing and wait time measurement projects, addition of these performance measures will significantly raise the value of these reports.

previous | next