The Regional Concept for Transportation Operations: A Practitioner's Guide

3. Developing an RCTO – Key Insights for Success

The demonstration site leaders embarked on developing an RCTO in collaboration with others in their region with little guidance on the process. They were forced to experiment with techniques to maintain participation among their partners and reach consensus. Throughout the demonstration initiative, development activities such as meetings and workshops were observed for lessons on what worked effectively and what did not. In addition, the RCTO leaders participated in regular conversations on their efforts and reported on their experiences, including both challenges and successes.

This chapter contains several insights conveyed by the RCTO demonstration site leaders or drawn from observations. It is intended to provide assistance to regions looking to develop an RCTO in the form of ideas or approaches to consider. The insights are not meant to be prescriptive. The insights discussed and examples offered in the sections relate to the following topics listed in the table below.

| Section in Chapter | RCTO Development Topic |

|---|---|

| 3.1 The Motivation Leading to an RCTO | Need for Improved Regional Operations at the Core of Motivation |

| Need to Work Collaboratively – A Necessary Element of RCTO Motivation | |

| Need for a Strategic Approach – A Necessary Element of RCTO Motivation | |

| 3.2 Collaborative Forum for Developing an RCTO | Organizing a Collaborative Forum |

| Establishing Champions and Leaders | |

| Engaging Participants | |

| Maintaining Participant Involvement | |

| Gathering Support From Elected or Appointed Officials and Agency Leadership | |

| Establishing a Process for Gathering Ideas and Making Decisions | |

| 3.3 Linking the RCTO and the Planning Process | Linking the RCTO and the Planning Process |

| 3.4 The "What" and "How" of the RCTO | Establishing Clear Operations Objectives |

| Creating an Approach | |

| Defining Supporting Elements of the Approach – Relationships and Procedures, Resource Arrangements, and Physical Improvements |

3.1 The Motivation Leading to an RCTO

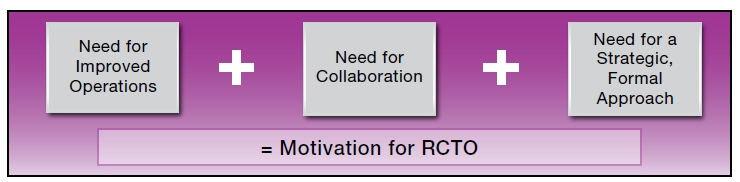

The path to an RCTO begins with a recognized need to improve regional transportation operations through collaboration using a formal, strategic approach. This recognized need referred to as the motivation for an RCTO has three crucial components: the need to improve regional transportation operations, the need to accomplish the improvements through regional collaboration, and the need to make these improvements in a sustained, formalized, and strategic manner. All three of these needs must be present for the RCTO to be considered as a tool for the region.

Figure 9. The Three Crucial Components to the Motivation

for an RCTO

Need for Improved Regional Operations at the Core of Motivation

At the core of the motivation for developing an RCTO is the need to improve regional transportation operations or some aspect of operations such as arterial delay, traffic incident management, or transit system management. This need determines the functional scope of the RCTO. As mentioned previously, the functional scope of an RCTO can be a single operations area such as traffic signal management, a collection of related areas, or a capability that cuts across multiple areas such as coordinated communications. The need to improve regional operations can come to the forefront in the region in several ways.

Frequently, the need is elevated from the "grass roots" through operating and planning agency staff or set as a priority from the "grass tops" through local elected officials or other high-level decisionmakers.

Motivation to Improve Regional Operations May Come from High-Level Decisionmakers

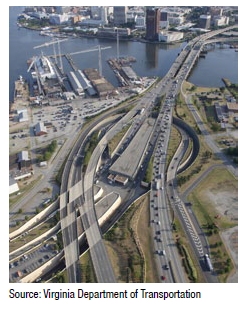

In both Hampton Roads and Portland, the development of the RCTO was set in motion by local elected officials who demanded improvements in the delay caused by traffic incidents. In Portland, a high-ranking elected official called for improvements in traffic incident management after witnessing extensive delay caused by a minor incident. The elected official brought together transportation executives in the City of Portland and other stakeholders to make changes to the way traffic incidents are handled. Based on this strong need to improve incident management, the RCTO was selected as the tool to make strategic and coordinated improvements in traffic incident management.

In Hampton Roads, traffic incident management is a hot button issue because of the bottlenecks created by the numerous bridges and tunnels that give the Hampton Roads region its unique transportation system. When an accident occurs near a bridge or tunnel, it is easy for traffic to become backed up quickly. The Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization's board of elected leaders called for regional planners and VDOT to organize and improve incident management throughout the region following a major traffic incident on a bridge in the region. The MPO board told them to come back and give regular updates on their progress. This provided the motivation to improve operations that led Hampton Roads to develop an RCTO for guiding their work towards better traffic incident management in the region.

Motivation May Arise from the Grassroots

In contrast, the motivation for operations improvements in the Tucson metropolitan region and Southeast Michigan were established through a grassroots effort where the needs for operations improvements for the region were identified through meetings between engineers and other senior staff from operating agencies in the region and interviews with key staff members conducted by RCTO development leaders. In the Tucson region, the lack of staff time and/or staff expertise to retime, coordinate, and manage traffic signals regularly within each individual agency's jurisdiction was a common issue that arose out of discussions with operating agencies in the region. Given that arterial roads in the Tucson region were becoming even more vital due to the major reconstruction effort just beginning on Interstate 10 through Tucson, the Tucson RCTO working group decided to use arterial management as one of their focus areas in their RCTO.

The Tucson RCTO working group was motivated to focus on work zone coordination as well in their RCTO because of a combination of needs expressed by operating agency staff in the RCTO meetings and interviews as well as a new policy by the area's Regional Transportation Authority Board:

to (1) encourage construction planning and phasing which limits the impacts of construction on parallel routes, and (2) encourage planning and phasing of safety, intersection, ITS and other program improvements so that they may be in place in advance of major construction on a nearby parallel corridor so as to facilitate traffic flow that may be impacted by construction of the corridor.29

The motivation for a third focus area of the Tucson area RCTO came out of the previous development of the Pima Association of Governments Intelligent Transportation System Strategic Deployment Plan. During the ITS Plan development, PAG's Transportation Systems Subcommittee developed a vision for the ideal traveler information system in the Tucson metropolitan region. The RCTO working group used that vision to set the direction for the RCTO element on improving traveler information.

In Southeast Michigan, the specific motivation to improve regional transportation operations that motivated the development of the RCTO also grew out of common needs and priorities identified by operating agency staff. The Southeast Michigan RCTO Planning Group with the support of its consultants facilitated meetings with groups of operations practitioners from at least nine agencies in the region to elicit the operations needs and priorities of the staff. The planning group found several common themes emerging for improvements such as establishing a common communications system among operating agencies, improving safety and efficiency of incident clearance, retiming traffic signals, and identifying priority corridors for operations investments.

Need to Work Collaboratively – A Necessary Element of RCTO Motivation

The motivation for an RCTO also includes the recognition that the desired improvements to operations in the region require a collaborative approach involving multiple agencies, jurisdictions, or modes. The interconnected nature of the regional transportation system requires collaboration between the operators of each element in order to get the best performance from the system. Operators who work with the public on a regular basis know that travelers do not care about the jurisdictional divides among the roads and rails they use. Travelers expect a seamless experience and operators must work together to provide that. The primary purpose of an RCTO is to focus the efforts of multiple agencies in the region so that travelers can access a safe and efficient transportation system regardless of jurisdiction or mode. An RCTO helps guide operators and planners toward a common objective through an agreed-upon approach.

Each of the RCTO demonstration sites viewed collaboration as necessary to improve regional transportation operations. The sites each had a history of successful collaboration and through these collaborative efforts came to recognize the value of working together as a region to address operations issues. In the Portland area, the Transportation Portland Technical Advisory Committee (TransPort TAC) is the primary forum for collaboration on regional transportation operations. Members of this group served as advisors for the RCTO demonstration initiative.

In Tucson, the primary forum for regional operations collaboration is the Pima Association of Governments Transportation Systems Subcommittee, first known as the ITS Working Group. This group formed the basis of the PAG RCTO working group.

Much of the regional operations collaborative work in the Southeast Michigan region centers on incident management. The region's incident management committee has evolved over the past decade into a forum for discussion concerning many aspects of regional operations.

In Hampton Roads, regional collaboration on transportation operations dates back to the formation of the Hampton Roads ITS Committee in the early 1990s under the guidance of HRTPO. The committee has expanded in scope and membership over the years, now includes public safety participants, and is named the Hampton Roads Transportation Operations Subcommittee.

Need for a Strategic Approach – A Necessary Element of RCTO Motivation

The third crucial component in the motivation to use an RCTO is the need for a strategic, formal approach to improving operations through collaboration. Through developing an RCTO, the participants define an operations objective and an approach for achieving that objective including relationships and procedures, resource arrangements, and physical improvements. While this model could be used for developing a strategic plan for a variety of transportation needs, the issue addressed by an RCTO should be complex enough to justify the effort needed to develop the elements of an RCTO. For example, retiming one signal near a jurisdictional boundary may not require a formal, strategic approach. An operations need that required developing an ongoing traffic signal retiming program for several jurisdictions, however, would be a prime candidate for an RCTO.

The RCTO leaders in Portland saw the RCTO as a way to harness the energy and momentum begun by the elected official to make improvements in traffic incident management. The motivation to develop an RCTO for traffic incident management in Portland arose from the need to collaboratively make strategic, deliberate decisions regarding a complex operations area: traffic incident management. Without a formal approach, Portland risked a piecemeal approach that would not fully resolve the issue.

RCTO Developers Motivated to Provide Continuity in the Event of Staff Changes

At the outset of the RCTO demonstration initiative, the Portland RCTO leaders were motivated in part to develop an RCTO to provide continuity to their collaborative efforts despite staff changes. Much of the operations collaboration in Portland is based on personal relationships among the various agencies' staff, and the operations leaders in the area wanted to provide for their successors an idea of how they work together, what their priorities are, and what they want to accomplish.

RCTO Developers Motivated to Raise Visibility of Operations in Planning Community

Additionally, Portland was motivated to develop an RCTO in order to raise the visibility of operations at the metropolitan planning table. The RCTO initiative in Portland was very much an effort to give operations more of a formal role in the planning and project review process at the metropolitan level. The Portland area succeeded in this effort on several accounts that will be described in later sections of this guide.

3.2 Collaborative Forum for Developing an RCTO

The foundation for developing an RCTO is the people working together within a collaborative structure that offers a forum to share ideas, make decisions, and commit to improving operations on a regional level. Because of the inherent differences among contexts for regional operations across the United States, there is no single collaborative structure that is recommended for developing an RCTO. The individuals and agencies that need to be involved differ depending on the focus of the operations improvement in both functional and geographic scope. The host or convener for the collaborative forum may be the MPO, the State DOT, or another entity within the region. Even though a one-size-fits-all solution cannot be proposed, there are approaches to organizing to build an RCTO that worked for the demonstration sites because of their individual circumstances and visions for the RCTO. Those approaches are detailed below to provide possible models for other regions.

Organizing a Collaborative Forum

Build on an Existing Collaborative Group

Each demonstration site had a strong history of regional collaboration for operations and each site built off the foundation of existing relationships to advance an RCTO. Tucson and Hampton Roads used their existing collaborative forums for regional operations for developing their RCTOs.

In the Tucson region, the regional operations stakeholders found it unnecessary and undesirable to add another layer of organization to their efforts. The individuals participating in the existing Transportation Systems Subcommittee at the Pima Association of Governments were often the same individuals who were needed to support the development of the RCTO. Therefore, the RCTO leaders essentially extended the meeting of that group by another hour during the RCTO development phase and handled the RCTO work during that hour. Most of the TSS members participated in both the Transportation Systems Subcommittee meeting and the RCTO development meeting afterwards. The leader of the RCTO was also the convener and host of the Transportation Systems Subcommittee. Although Tucson struggled for participation in the RCTO meetings during the early phases of the RCTO development process, the technique of piggy-backing onto an existing group that had the desired members worked well for the development as well as implementation. During the implementation of the RCTO, the operations initiatives begun with the RCTO were successfully integrated into the agenda of the Transportation Systems Subcommittee.

In the Hampton Roads region, the RCTO leaders developed a working group by drawing from an existing subcommittee of the Hampton Roads Transportation Technical Advisory Committee (Hampton Roads Transportation Operations Subcommittee) and one external committee established by local incident management leaders (Hampton Roads Highway Incident Management (HRHIM) Committee). Historically, the membership of the Hampton Roads Transportation Operations Subcommittee had been traffic engineers and planners, whereas the HRHIM Committee consisted primarily of public safety representatives. In recent years, both committees experienced "cross-pollination" of participants as each saw the need to work with the other field. The call to improve traffic incident management strategically using an RCTO provided the impetus to form a common forum where both public safety and transportation engineers and planners were committed to meeting regularly and working together.

Form a Tiered Collaborative Structure with a Strong Mandate

The Portland region received a strong mandate from an elected official, the city transportation commissioner, to improve traffic incident management. The commissioner brought together City of Portland agency leaders to form the Portland Operations Steering Team (POST). Members in turn charged their respective staffs to work together to come up with a menu of solutions that the POST would select from to address traffic incident management. The staff-level working group used the RCTO as the tool to guide them in developing a collaborative strategy containing the needed menu of actions.

Lesson LearnedThe two-tiered organizational structure for making transportation improvements on a regional basis was highly efficient and effective in Portland. The combination of agency leaders and technical staff proved important to making major strides towards operations improvements on a regional level. |

In many ways, the two-tiered organizational structure for making transportation improvements on a regional basis was highly efficient and effective. Both the POST and the staff-level working group were directed by someone with authority over them to work together and develop a solution. The commitment of those involved was clear: operations efforts had become part of these staff members' jobs. The structure used by Portland was also effective because it relied on individuals within participating agencies to perform the functions that they were best suited for: agency leaders provided guidance and made high-level decisions while senior technical staff shaped the technical approaches needed to deliver on the leaders' vision. This combination was effective in making strides towards operations improvements in Portland.

Establishing Champions and Leaders

Ensure at Least One Committed Champion

As common sense would dictate, when multiple players are working together, the effort needs at least one person to serve as the champion for the group, someone who feels strongly that the effort is deeply needed and is willing to make sure it is successful. Often the champion has a clear vision of the desired outcome, brings together the needed parties, ensures that they are engaged, and works to get the support needed for achieving the desired outcomes. Prior to the RCTO effort focused on TIM in Portland, the demonstration project staff attempted to initiate an RCTO around traveler information. This was a need identified by members of the TransPort TAC, the inter-agency ITS staff committee, but the RCTO never came to fruition, in part due to the lack of a committed champion.Engaging Participants

The progress that can be made on improving regional operations through an RCTO is limited by the participants that can be brought into the collaboration. For example, a group cannot coordinate its traffic signals with a neighboring jurisdiction if the signal owners for that jurisdiction are not at the table. This also applies to operations function. If transit agencies are not participating in a collaborative effort to provide a comprehensive traveler information service to the public, the service will only be able to include the travel modes at the table.

All of the demonstration sites had to make concerted efforts to reach out and engage the participating agencies, stakeholder groups, and individuals within those agencies or groups that were deemed necessary for reaching the desired outcomes of the RCTO. In Hampton Roads, the RCTO leaders at the MPO and State DOT were able to get the participation and commitment of public safety groups in the region for the RCTO on traffic incident management because they had done the work of reaching out to police, fire/EMS, and other first responders approximately 5 years prior during the update of the region's ITS strategic plan. One of the six working group sessions during the update process was devoted to issues of emergency management, and one of the six program areas in the ITS strategic plan focused on incident and emergency management.

The Tucson RCTO participants did not have an existing regular collaborative forum with first responders, so during an initial phase of the RCTO work in Tucson, the RCTO leader from PAG and the supporting consultants went to the Pima County Sheriff's Office and the City of Tucson's Police Department to determine the existing conditions for regional transportation operations in terms of who performs what function, where collaboration currently exists, and where improvements are desired from a regional operations standpoint. Because of the broad distribution of fire departments across the region, the Tucson RCTO leaders struggled to determine how best to reach out to them for their input. RCTO leaders found that the best way to reach the fire community was to access the regional structure for fire departments in the area, the Pima Fire Chief's Association. Although the participation of public safety stakeholders during the RCTO development in Tucson was not substantial enough to make traffic incident management one of the focus areas for the RCTO, the outreach created the foundation for a collaborative effort to improve incident management during major freeway construction 2 years later.

Educate Potential Participants on the RCTO with Simple, Clear Communication

A common challenge for the RCTO demonstration site leaders was presenting the RCTO tool in a way that potential RCTO development participants in their regions could understand and buy into. In Southeast Michigan, a mission statement, RCTO vision, and overall goals for the RCTO were enunciated so that as RCTO leaders reached out to stakeholder agencies in the region, those stakeholders had a better understanding of what the RCTO covered and what it did not. This is important in helping potential participants understand how the RCTO relates to their work and whether this is something they want to participate in. Lesson LearnedBecause of the broad dispersion of fire departments across the region, the Tucson RCTO leaders struggled to determine how to best outreach to them and get their input. They found that the best way to reach the fire community was to access the regional structure for fire departments in the area, the Pima Fire Chief's Association. |

In Tucson, the RCTO leaders developed a two-page handout on the vision for the Tucson area RCTO. The handout answered questions such as "What do we mean by a Regional Concept for Transportation Operations?" and "How will the RCTO affect the way my agency is operating?"

In Portland, the RCTO leader used the term RCTO as sparingly as possible because he felt that the title could be an impediment to understanding the very basic nature of what the RCTO developers were doing: specifying what they wanted to accomplish and how it would be accomplished. To audiences concerned with Federal and State policy, he explained that the RCTO is a way to "ride a wave of mandates" to plan for operations and better operate and manage the system. He observed that although the RCTO may be a difficult concept to convey, everyone can understand getting "more bang for your buck" by operating better and it is easy to demonstrate the need to talk about how to do this. This is where the RCTO can come into the discussion.

While reaching out to stakeholder agencies, the Southeast Michigan RCTO Planning Group found that it needed to reassure operating agencies in local jurisdictions that the RCTO would not take over their operations. The group also found it important to clarify the term "operations" in the context of the RCTO.

Ensure that the Individuals Necessary for Taking Action on the RCTO are at the Table

One of the greatest challenges faced by the RCTO demonstration sites was establishing a sense of ownership for the RCTO among the individuals or organizations that were required for implementation. This was particularly an issue when staff members from the MPO who were not operators served as the champions and facilitators of the RCTO. In the situations where those individuals with implementation authority were involved in making decisions on the objectives and approach for the RCTO, more progress was made initially in implementing the RCTO. In Tucson, engineers responsible for traffic signal operations participated in making decisions on how to approach a collaborative venture in signal improvements. Subsequently, there has been significant progress made on implementing a joint signal program for the area under the guidance of these individuals. In Southeast Michigan, the RCTO development team faced challenges as they worked to designate current committees in the region as champions and leaders for the four RCTO objectives and approaches that they had developed. Those who had not participated in making decisions on what was going to be done seemed less inclined to adopt the RCTO as part of their agenda or upcoming activities.

In Tucson, the RCTO participants had identified work zone coordination as one of the top three areas that they wanted to make progress on in the region, but the RCTO leader recognized that the staff members currently in the RCTO working group were not the individuals with the authority or knowledge to make improvements to work zone and construction scheduling. The RCTO leader reached out to the participating agencies and was able to bring the right individuals together to form a new working group on work zone coordination. The members recognized the need to coordinate and have made progress toward that end.

Host a Regional Transportation Operations Partnering Workshop

Early on in the RCTO development process, the operations stakeholders of the Metro Detroit area held the Detroit Area Operations Partnering Workshop, hosted by the Michigan DOT. The workshop highlighted the benefits of collaboration in the region and provided an opportunity for individuals from different agencies across the region to develop or strengthen their connections. Speakers briefly highlighted best practices for coordination and informed attendees of opportunities to collaborate and access regional resources. This workshop helped to raise the awareness of regional operations collaboration and provided the foundation for building a community that would support regional operations efforts. A year following the partnering workshop, the RCTO leaders in Southeast Michigan held a second workshop to give stakeholders a chance to provide input into the RCTO.

Gain the Participation of the State Department of Transportation, a Critical Operations Stakeholder

Each of the four RCTO demonstration sites found that it was imperative to have the buy-in and commitment from the State DOT for the RCTO. The State DOT owns and operates a major portion of the regional transportation system and frequently has resources, expertise, and the authority to make it a significant partner in any regional transportation operations effort. In Southeast Michigan, Michigan DOT was one of the leaders of the RCTO, and its contributions were critical in making progress, especially toward the RCTO objectives in information sharing and retiming traffic signals. Some local traffic signal operating agencies lacked the time to carry out traffic signal retiming, even if funding for the retiming could be provided with CMAQ or other Federal funds. Michigan DOT stepped up to offer assistance in managing the contractors that the local agency could use to retime their signals. Without such assistance, the local agency would not have even applied for the CMAQ funding in the metropolitan planning process. In support of increased information sharing between transportation stakeholders in the region, Michigan DOT created a utility to share video from their freeway cameras with other agencies over the Internet.

Maintaining Participant Involvement

Maintain Participation in the RCTO by Showing Participants the Near-Term BenefitsThe key to establishing and maintaining the participation of operators in the RCTO development process is to clearly identify the benefits that the operators can gain from the collaborative effort and work to deliver those benefits as soon as possible. Operating agencies are traditionally under-staffed, leaving staff with many competing responsibilities. Additionally, operations personnel are accustomed to performing operations-related duties and typically do not focus on planning activities. This is why is it important to show short-term benefits to operators and demonstrate that the RCTO effort addresses operators' issues and concerns.

Lesson LearnedTucson found it effective to show the collaborating operations staff that working together on an RCTO was not just a planning exercise, but a way to improve their ability to carry out their responsibilities successfully and efficiently. |

The RCTO leader in Tucson made this a high priority in the development process after finding trouble engaging the operations staff in developing a vision and goals for the RCTO. To keep the RCTO participants engaged, the leader capitalized on objectives and actions that would help the operators handle their responsibilities more effectively and efficiently, such as funding and staff assistance in signal timing. As an example, during one RCTO meeting the RCTO leader invited the Arizona DOT to highlight the opportunities for local operating agencies to participate in joint procurements with the Arizona DOT to save money on needed equipment and software. Tucson found it effective to show the collaborating operations participants that working together on an RCTO was not just a planning exercise, but a way to improve their ability to carry out their responsibilities successfully and efficiently.

Gain the Attention of Operations Participants by Focusing on Actions and Resulting Projects

Both Southeast Michigan and Tucson have learned that it is easier to gain the attention of operations participants by focusing on actions and projects that could come out of the RCTO. When conducting stakeholder interviews, the Southeast Michigan team learned that operators were more interested in discussing action rather than abstract goals and visions. Going a step further and translating the RCTO actions into specific projects that can be used to gain agency support and commitment and obtain the resources necessary for implementation helped to make the RCTO tangible and meaningful to operators in Tucson.

Bring Participants to the Table for Only Pertinent Discussions

Tucson found it hard to get the attention and participation of the first responder stakeholders, transit stakeholders, and the Native American tribal stakeholders. The Tucson RCTO leader found that the best way to involve participant groups not central to the focus of the RCTO is by only inviting them to the meetings that were pertinent to them. This demonstrates to the stakeholders that their input is necessary and that their time will not be wasted.

Formalize Agreements

An RCTO is a "living document" in the sense that it is not intended to be a report, project, or program. It is an agreement-a commitment-among participating agencies and jurisdictions to one or more agreed-upon objectives and a set of actions, institutional relationships, and resource allocation decisions that address regionally significant needs and opportunities.

Regional value accrues when all of the participating agencies and jurisdictions work together to improve regional transportation system performance through operational objectives established in the RCTO.

The institutional mechanisms for "acting together" can vary from informal arrangement between operating agencies in neighboring jurisdictions to formal memoranda of understanding (or "Memoranda of Regional Cooperation"—MORCs—as are used in some jurisdictions) to legal entities or authorities that receive funding from participating jurisdictions and are established to carry out many of the activities described in the RCTO. However participating entities choose to institutionalize their relationship, what is important is that they maintain their commitment to the operational objectives that were agreed to and that drive the RCTO.

As an initial step for implementation of the Southeast Michigan RCTO, the leading organizations supporting the RCTO signed a memorandum for regional cooperation. The memorandum was signed by the Michigan DOT Metro Region Engineer, a Captain and District Headquarters Commander of the Department of Michigan State Police, and the Executive Director of SEMCOG. It affirms that commitment of the participating agencies to supporting work in toward the objectives defined in the RCTO. Through the memorandum, SEMCOG indicated its commitment to serve as the RCTO facilitator and to coordinate activities such as monitoring and updating the RCTO. Additionally, the RCTO development group for Southeast Michigan has established ongoing meetings on a quarterly basis to provide oversight and support to the existing committees that have taken on implementing the RCTO.

Gathering Support From Elected Or Appointed Officials And Agency Leadership

Gaining the support of elected or appointed officials, agency leadership, and other senior decisionmakers within the region for the collaborative operations improvements in an RCTO is crucial to successful implementation. An RCTO requires resources to develop and to implement such as staff time, equipment, policy commitments, new operating procedures, or funding. Obtaining buy-in and commitment from those leaders that decide how resources are used is vital to an RCTO. RCTO demonstration site leaders observed that gathering that support early on in the development of the RCTO is highly important.

Identify an Advocate for the Effort at the Executive Leadership Level

The operations area being addressed in an RCTO needs someone who can advocate for the effort at the executive leadership level. This is often best accomplished by someone at the executive level in the region since a peer can have more influence than someone at a less senior level. Although having a champion in a high-level position-as in the case of Portland, where the city transportation commissioner served as the champion for the TIM effort-is a highly effective approach to making changes within a region, the improvements made at the other RCTO demonstration sites show that this does not always need to be the case.

In the Tucson region, a program manager within the MPO with a history of facilitating operations efforts served as the RCTO champion. He led the group, worked to motivate the necessary players, and took the ideas for transportation operations programs that came out of the group to his management and the MPO board to get support and resources. The Tucson RCTO champion also used regular meetings among the MPO Transportation Director and the local DOT directors to keep agency leaders informed regarding key issues and gain support for RCTO initiatives.

In Hampton Roads, the championship was shared between two senior staff at HRTPO and the Virginia DOT who had a long history of working together for coordinated operations. These senior staff members provided the vision and leadership to help give the group direction and maintain its trajectory and worked to get data and personnel resource commitments from the MPO and the State DOT.

Create Awareness of the RCTO Effort and its Benefits by Asking Participants to Educate their Management

The Portland and Tucson RCTO leaders recommended that the staff members participating in the development of the RCTO ensure that agency leadership is aware and supportive of the effort. The Portland RCTO leader noted that representatives of each primary stakeholder agency were involved in the oversight committee, but they were not the decisionmakers. From that experience, the Portland RCTO leader recommended that when forming the RCTO advisory or development committee, it is important to try and climb the institutional ladder to make sure that the senior level management has a solid awareness of what is going on. This is likely to pay off as representatives need resources and commitment from their agencies to implement the RCTO.

In Tucson, the staff members that participated in the RCTO working group were encouraged to take the options for operational improvements back to their agency management to get feedback. This was important because most of the agency personnel participating in the group were not authorized to make commitments or decisions for the agencies they represented.

Develop a Monthly Regional Operations Newsletter

As part of the RCTO demonstration initiative in Portland, the RCTO leader hired to work at Metro developed a transportation operations program within the MPO to increase the coordination between planning and operations in the region. To raise the visibility of operations and gather support from MPO committee members, the RCTO leader in Portland produced and distributed monthly transportation operations program updates in the form of a quick, one-page newsletter. The newsletter was distributed to Metro's technical committee. The newsletter grabs the attention of the reader with a snapshot of a mobility performance measure such as the change in percent of congested travel from July of 2005 to July of 2006. A description and the benefits of a newly implemented operations strategy are given. This is followed by a list of operations program activities in the past month and upcoming opportunities for participation.

Make Presentations on the RCTO Effort to the MPO Technical Committee or Board

Even in the cases of Portland and Hampton Roads, where elected leaders were directing planning and operations agencies to work together to make operational improvements, the outreach had been conducted by the staff to raise the visibility and relevance of operations solutions. In Hampton Roads, the leaders of the early ITS Working Group in the 1990s conducted an educational campaign on the need for ITS by giving presentations to boards and committees across the region. This helped to set the tone and support for ITS and operations among leaders in the region.

In Portland, staff members who had been working together across agency lines for operations realized that they did not have the attention from elected officials on the use of ITS and operations so they began a concerted marketing effort during the start up of the RCTO. As one of the initial outreach steps, the RCTO leader in Portland made presentations to the technical committee of the MPO board to inform them of the objectives and strategies being proposed for improving operations.

Develop a Region-Specific Brochure on the Tangible Benefits of Regional Operations

TransPort TAC, which coordinates ITS across the region, developed a report and companion brochure titled: Metropolitan Mobility The Smart Way in October of 2006. The goals of this report and brochure were two-fold:

- To increase awareness and understanding among the region's decisionmakers regarding ITS and the ways in which it can help transportation agencies in the Portland metropolitan area manage congestion and improve safety in a cost-effective manner.

- To focus attention on the benefits of collaboratively implementing system management strategies and intelligent transportation systems.30

|

Figure 10. Metropolitan Mobility The Smart Way

Executive Summary by Metro and ITS Oregon |

The report and brochure highlight the tangible benefits that the Portland region has already gained from ITS and operations solutions. These materials helped to make the case to public officials for operations solutions that came out of the RCTO.

Host an Executive-Level Panel Discussion on the Need for Improved Transportation Operations

The leader of the Portland RCTO helped to organize an executive-level panel discussion sponsored by ITS Oregon for the release of the Metropolitan Mobility Smart Way report. Nearly 100 elected officials, legislators, and executive-level transportation professionals in Portland and throughout Oregon attended this breakfast meeting to hear the Oregon Transportation Commissioner, the Federal Highway Administrator, and other top officials speak about the need for improved mobility through ITS and operations. The meeting was successful in gaining agreement among senior decisionmakers on the need for operations improvements.

Publicize the Cost of Congestion and Other Mobility Issues

One of the reasons for the elected official's support for improved operations in the Portland region was the increased awareness of the true costs to congestion. In December 2005, the Portland Business Alliance, Metro, and the Port of Portland published a report entitled "Cost of Congestion." This report brought to light the enormous price that is being paid by travelers and businesses for the time and fuel wasted by congestion. By putting a price on transportation performance issues, stakeholders can gain the attention and support of elected and appointed officials for operations improvements recommended by an RCTO.

Gather Traffic Reporters for a Briefing on Operations

Another technique used to bring awareness to the issue of congestion and operations improvements in Portland was gathering together traffic reporters for a briefing on operations. The Portland RCTO leader called together traffic reporters in the region for donuts and a talk about ITS. From that meeting, the RCTO leader got editorials and front page stories on the ITS improvements being used in Portland and the need to make more improvements. From this experience, the RCTO leader found that reporters are interested in this subject and want to talk to transportation professionals, but it may require reaching out to them...and perhaps providing donuts.

Establishing a Process for Gathering ideas and Making Decisions

At the heart of developing an RCTO is decisionmaking. An RCTO provides a framework to guide collaborating participants on what decisions will need to be made in order to move forward together to improve transportation operations. Those decisions are essentially about answering the questions "what do we want to accomplish" and "how are we going to get there." A well thought-out process for generating ideas and making decisions is necessary for developing an RCTO that can be successfully implemented.

Each RCTO demonstration site had to invent its own process for gathering ideas and making decisions. In Tucson and Southeast Michigan, ideas for the RCTO objectives and approach came from the grassroots through interviews with managers and senior staff at stakeholder agencies and workshops. The RCTO leaders and consultants conducted these interviews and combined the results to identify themes for operations improvements common to multiple stakeholder agencies. In Tucson, the interviews also involved documenting the current operations policies, practices, procedures, and existing institutional relationships in the region.

These interviews helped to identify potential new members for collaborative regional transportation operations efforts and identify opportunities for regional operations improvements. Through the interviews, the RCTO leader in Southeast Michigan, with the support of the consultants, identified the operations objectives for the RCTO. While there was interest among operating agencies for the operations objectives identified in the interviews in Southeast Michigan, one barrier that the RCTO team later encountered was a lack of a champion willing to lead the achievement of the objective.

The RCTO leaders and consultants in Tucson and Southeast Michigan helped to shape the information gathered from the stakeholders and brainstorming meetings with the RCTO development group. This information was then presented to the development group to discuss, modify, and either accept or reject.

Enable Senior Staff to Develop Options for Leadership to Select

During the development of the RCTO on traffic incident management in Portland, ideas for potential approaches to bring about the objective set by the commissioner were generated by senior agency staff members who met regularly. They made decisions on which approaches were feasible and could bring about the desired objective. The agency leaders then decided by reaching consensus on which of the actions to improve TIM should be pursued.

Conduct RCTO Meetings On-Site at Participating Agencies

Several of the RCTO demonstration sites conducted RCTO development group meetings on-site at participating agencies. They would rotate the location of the meeting so as to get a greater diversity of participation in the process. They recognized that where one or two stakeholders from a particular agency might attend a meeting at another location, more than a dozen might attend a meeting at their own agency.

Use Smaller, Less Formal Meetings to Talk Over Recommendations in Detail

The RCTO leader in Tucson discovered that some of the most productive RCTO development meetings occurred when there were a small number of individuals in a less formal setting. This seemed to encourage the participants to talk more freely and delve into the details of the RCTO. While small meetings were more productive, participants from each primary collaborative agency had to be present.

Ensure Consultants Support the Forum Rather Than Lead It

In each demonstration site, additional support was brought in to assist in the development of the RCTO. Southeast Michigan, Tucson, and Hampton Roads hired consultants who were familiar with the agencies' and regions' institutional dynamics, and in Portland a temporary full-time employee was brought in to Metro, the MPO, and funded through the City of Portland. The consultants served as facilitators of the regular RCTO development meetings, documented decisions, organized workshops, and helped to draft the RCTO document.

While outside support may be required to make developing an RCTO possible in some areas where agency staff has little available time or facilitation expertise, it is necessary to ensure that the outside support does not take the place of the leadership and decisionmaking that must come from those in the region. The danger faced by regions that have consultants lead instead of support the development of the RCTO is that the RCTO becomes a document that sits on a shelf once the consultants leave. The ownership of the RCTO must reside with the organizational representatives that have the enthusiasm and capability of putting the RCTO into action.

3.3 Linking the RCTO and the Planning Process

Connecting the RCTO to the transportation planning process offers benefits for planners who are interested in advancing cost-effective strategies to improve regional transportation system performance and operations-oriented partners who are seeking regional support for their joint efforts. An RCTO is one opportunity among several to link transportation planning and investment decisionmaking to management and operations.

By linking to the planning process, partners can gain recognition within the region for operations and increase credibility with elected leaders whose support may be crucial in advancing operations. RCTO partners can ground their work in formally established regional needs, goals, and objectives. Additionally, they can increase the stability of their partnership by selecting the MPO to be an impartial and long-term host for the collaborative development and implementation of their RCTOs. RCTO partners may also be able to influence the selection of performance measures and data collection procedures used during regional planning to better track the progress toward the RCTO operations objective.

Use an MPO to Provide a Neutral Table and Convene Agencies from the Region

One of the keys to a successful collaborative effort like the development and implementation of an RCTO is finding an appropriate host or convener for the collaborative forum. Two qualities that were important to the demonstration site representatives were neutrality and coordination experience with the necessary participants. Although the MPO need not be the host for developing an RCTO, in three of the four RCTO demonstration sites, the MPO served as the host and convener. In the fourth site, HRTPO and the Virginia DOT shared the responsibilities. In some cases, operating agencies desired the MPO to take on an even greater role in facilitating the implementation of operations strategies than the MPO saw as part of its mission. The Tucson RCTO site leader noted that the MPO was able to be an effective host because it was viewed as having a regional perspective and being a "safe place" to develop the RCTO in that it does not have operating turf. The MPO, PAG, also had the most experience among the participating agencies of coordinating among each of the operators in the region.

Demonstrating that the MPO was valued in the Tucson region as the host for regional operations forums, transportation operating agencies sought out PAG to coordinate a multi-agency effort to increase traffic incident management following the development of the RCTO. As part of this effort, PAG held an incident management workshop and has hosted weekly meetings among transportation, police, fire, and others to identify issues, resolve concerns, and conduct workshop planning.

Portland RCTO Demonstration Grant Led to Permanent Linkages between Planning and OperationsThe Portland, Oregon RCTO demonstration site participants viewed the demonstration grant as an opportunity to make great strides in linking planning and operations. They saw this as an opportunity to raise the visibility of operations throughout the region and with executive leadership and transportation planners in particular. The RCTO was also a way to encourage more strategic thinking about operations in the region. The demonstration site grant in Portland was used to fund a principal planner for 2 years at the area's MPO, Metro. This staff person was to lead the development of the RCTO as well as build a transportation operations program at Metro. The RCTO development occurred concurrently with the update of the region's metropolitan transportation plan. The RCTO process enhanced the attention given to operations during the plan update and led to policy language that set out a strong commitment to including operations solutions in the plan. Metro also revised the TIP project ranking and selection criteria to include ITS architecture consistency and travel time reliability and promoted the inclusion of ITS elements within conventional projects. Additionally, a programmatic allocation in the TIP for ITS projects was created because ITS projects traditionally struggled to compete against other projects. Metro approved $3 million in 2010-2011 for ITS projects. Metro, in collaboration with operations stakeholders, then developed an operations refinement plan to determine which operations needs to address through the new ITS program. During the period of the RCTO demonstration grant, the temporary staff person at Metro brought on to lead the RCTO development was able to demonstrate the need for an operations program manager at Metro and the value of operations expertise in an MPO. A new permanent staff position at Metro was formed for a principal planner to head up the operations program. Contact: Deena Platman, Metro at deena.platman@oregonmetro.gov. |

Similarly, HRTPO had been the organization frequently called on by operators in the region to connect them to other operators on a case by case basis in the early 1990s. The MPO recognized the need for regional operators to coordinate with each other directly, and so it formed an ITS working group, an active group of transportation engineers, planners, and public safety representatives that meets regularly as a subcommittee of the MPO.

As the host of the RCTO effort, MPO staff at the demonstration sites also helped to advocate for the operations projects identified during the RCTO development within the plan and assist them in applying for funding through the TIP. At PAG and SEMCOG, the MPO work program funds were even used to support RCTO implementation activities such as improving the region's traveler information website and conducting a study to measure the performance of signalized intersections to identify priorities for signal improvements.

Revise Operations Objectives Requiring Regional Funds to Account for Programming Cycle

The Tucson RCTO team chose to extend the timeframe for some of their objectives because they were unable to get the necessary funding to accomplish those objectives within the 3-5 year timeframe. Due to the timing of the 5-year TIP cycle at PAG, the time available to the RCTO team was not sufficient to apply for, receive, and use the funding within the original timeframe. Instead of throwing out those objectives, however, the RCTO team compromised and extended the timeframe of the objectives to 5-10 years. The group applied for funding to support those objectives and the planners at PAG worked to establish an operations program that would facilitate funding availability in future years. Alternatively, the Portland RCTO group faced a similar challenge and chose to focus on objectives that could be accomplished with fewer resources, such as TIM training, improved procedures, and legislative changes.

Establish a Regional Funding Program for an Operations Area

Opening funding avenues for operations from sources such as the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) Improvement Program, Surface Transportation Program, and State, regional, or local tax programs is another compelling reason to link regional operations activities to the planning process. The ability of RCTO partners to apply and receive funding in the near term depends on the flexibility of the planning organization to allocate funding for management and operations projects. All projects need to be part of the metropolitan transportation plan (MTP) in order to be eligible for funding through the metropolitan planning process. In many regions, obtaining funding within one to two years is very difficult because all available funding is designated for specific projects many years in advance. In those cases, partners may choose to work to establish funding options for future management and operations projects while implementing an RCTO in the near term that relies on available resources and technology.

In Southeast Michigan during workshops with stakeholder agencies, the RCTO development group found that while there were significant needs from local agencies to retime traffic signals the agencies often did not have the staff or budget to do so. Because of these needs, part of the Southeast Michigan RCTO focuses on improving signal operations. Through this RCTO, a traffic signal retiming program has been incorporated into SEMCOG's 2030 metropolitan transportation plan and local agencies have applied for CMAQ funding to retime traffic signals.

Likewise the PAG RCTO included a regional traffic signal optimization program and applied for funding from the TIP to cover the signal program. Because the RCTO participants were unable to receive any funding through the TIP within 5 years, the RCTO participants extended the timeline of their RCTO and also looked for low-cost activities to support their operations objectives. During the development of the PAG RCTO, a transportation sales tax was passed and the RCTO developers were able to incorporate some of their traffic signal recommendations into the sales tax package.

3.4 The "What" and the "How" of the RCTO

The operations objective provides direction for the RCTO and the collaborative effort. Through developing one or more operations objectives, the RCTO participants answer the question "what will we work to achieve?" As mentioned previously, a highly effective operations objective is one that is specific, measurable, agreed-upon, realistic, and time-bound. In developing their operations objectives, the RCTO demonstration site participants had to find the middle ground between operations objectives that embodied the large impacts they wanted to make and selecting objectives that could realistically be accomplished within 3 to 5 years.

Operations objectives typically fall into two categories: outcome-based and activity-based. Ideally, an RCTO is built around a desired system performance outcome as experienced by the system users or travelers. This is the difference that the RCTO participants would like to make in their transportation system. In situations where an outcome-based objective is not feasible, an activity-based objective may be developed to guide improvements in system manager and operator activities. The operations objectives developed by the RCTO demonstration sites included both outcome- and activity-based objectives.

Identify Desired Objectives before Moving on to Solutions

One of the potential pitfalls in developing an RCTO is to begin developing solutions or projects before fully specifying and reaching agreement on an operations objective. This can lead to a collection of disparate activities and projects that are not strategically focused on reaching the outcome desired by the participants. Operators are typically more accustomed to taking action than to strategic planning and may have a tendency to jump to new technologies or operations strategies before reaching consensus on the desired outcome. Early on in the Portland demonstration initiative, the group struggled with creating an RCTO with a focus on traveler information. The RCTO leader in Portland realized that this was particularly difficult because they were focusing on how best to use traveler information rather than identifying the desired outcome for the traveler and then selecting the best strategies to reach that outcome.

Try Identifying an Operations Objective in Terms of Risk Management

The choice of whether to pursue an operations objective or not involves managing risk. Although this terminology is more common in fields such as asset management, the leader of the Portland area RCTO strongly recommended thinking of operations objectives in these terms. When embarking on developing an RCTO, the Portland RCTO group worked to frame the outcomes in terms of "where we are going" and "why it is worth getting there." It was helpful to examine the selection of objectives in terms of "how things turn out if we do not make this coordinated improvement to operations." Additionally, the leader found it helpful for the RCTO group to consider what the difference is to the citizen if the group pursued this regionally or not. By getting a sense of the risk involved in deciding not to pursue a given operations objective, the RCTO participants are able to focus on the outcomes that will have the greatest impact.

Identify Activity-Oriented Objectives to Support Outcome-Oriented Objectives

RCTO developers may find it effective to develop activity-based objectives that define improvements in operator performance that are believed to lead to the desired system outcomes. The Tucson region's RCTO provided a combination of system outcome objectives such as "Reduce traveler delay..." and activity-based objectives such as "Improve multi-agency coordination for large-scale work zones."31 Many of the objectives that described a desired system outcome had supporting activity-based objectives that helped to direct the participants in the specific activities that would help to accomplish the outcome. An example from the PAG Regional Concept for Transportation Operations is shown below:

Outcome-Oriented Operations Objective: "Reduce traveler delay due to incidents on major arterials and freeways within Tucson metropolitan areas."

Supporting Activity-Based Operations Objective: "Reduce incident response, duration and investigation times."32

While the desired outcome experienced by the user is stated, the operator activities that they will focus on improving to reach this outcome are also specified. This process of expanding an objective into a set of more specific objectives repeatedly until reaching tangible action items is a common practice in systems engineering and can be an effective and logical way to translate desired outcomes into actions. In the case of the RCTO, developing activity-based operations objectives begins a process of developing the RCTO approach.

Divide the Operations Area of Focus into Smaller Elements and Identify Any Needed Improvements in Each Element

Several operations focus areas can be broken down into smaller components. For example, traffic incident management can be divided into the detect, verify, response, clear, and recover phases. The RCTO participants in Portland looked at improvements that could be made in each phase to support the overall goal of reducing delay due to incidents. The ability to break the area down into its component parts was an effective method for facilitating a discussion of objectives and approaches to address a large and complex area.

Keep Scope of Operations Objectives Manageable

A common recommendation coming from the RCTO demonstration site leaders was to develop operations objectives that had a manageable scope and did not overextend the capabilities of the participants. The Tucson RCTO participants began with a large scope incorporating a number of operations areas and then narrowed down the areas and objectives they would pursue initially as they began evaluating how realistic each objective was. The Tucson and Southeast Michigan RCTO leaders both expressed that the operations objectives selected for the initial RCTO should focus on low-hanging fruit. This would allow for an "early win" that could garner additional support and momentum for the RCTO effort.

Create Performance Targets for Objectives using Baseline Data

Hampton Roads created a set of operations objectives that included both outcome-based objectives and activity-based objectives. The RCTO working group developed specific performance targets for many of the objectives. For example, the Hampton Roads objective "Decrease Incident Clearance Time" has an associated target of "Annually Reduce Incident Clearance Time by 5.5 Percent or 1.5 Minutes." This required a significant effort by VDOT to collect and analyze relevant data over time so that the RCTO development team could establish a reasonable target number for its traffic incident management objectives. To continue tracking system performance, VDOT brought in a full-time analyst to support the effort.

The operations objectives of the Portland RCTO were developed to support the overall goal that was articulated early on in the RCTO process: "Reduce unnecessary (excess) delay associated with minor (non-injury) incidents that occur on freeways within the City of Portland, Oregon." The details in the goal helped the RCTO developers to clarify their objectives, given in Section 2.1 of this guide. The Portland objectives are primarily outcome-oriented, but include one activity-based objective: "Reduce tow truck arrival and on-scene times." Due to a lack of baseline data and associated resources, the Portland RCTO objectives show the direction but not the magnitude of the improvements desired.

Identify Performance Measures to Track Progress toward Operations Objectives

Tracking progress toward operations objectives through performance measures is vital to supporting the successful implementation of an RCTO. Regular performance measurement gives the RCTO participants important feedback on the effectiveness of their activities so that they can change their approach if they determine that progress is not being made. Performance measures also allow RCTO participants to publicize their successes in quantifiable terms to garner additional support from decisionmakers and the public.

In Tucson, performance measures were identified once operations objectives were established. This provided them a check to make sure that their operations objectives were specific and measurable. Because the performance measures the Tucson participants identified were so data intensive, the RCTO members chose to simplify their measures in order to be practical given the data they could access.

Do Not Limit Operations Objectives Because of Performance Measurement Capabilities - Find Surrogate Measures While Working to Improve Capabilities

The ability to measure aspects of transportation system performance is growing in many regions across the country as transportation professionals incorporate new sources of data from roadside instruments and new performance measures are defined. While measurement capabilities are increasing, many regions are still limited in this area.

The Hampton Roads RCTO group created performance targets and measures for several of their operations objectives, but they faced challenges with others. They were unable to produce a specific performance target for their objective to "Improve Inter-Agency Communication During Incidents" because the region had not yet assessed the current state of communications through either qualitative or quantitative measures. To handle their lack of data regarding this objective, the RCTO team decided to develop a method of assessing communication by starting an annual survey of stakeholder agencies as part of their RCTO effort. This survey would ask responder agencies to identify progress made over the past year and steps for future improvement.

Additionally, the Hampton Roads working group was challenged to integrate their concerns about secondary incidents into this RCTO so that such incidents can be measured and tracked over time. The difficulty was due to the lack of a clear definition for secondary incidents. The RCTO working group resolved the issue by agreeing to the following definition of a secondary incident: "a visually confirmed incident within a queue that is formed by an earlier incident, or an incident that occurs while traveling in the opposite direction of an incident derived queue."33 The RCTO working group is also still refining the process of collecting data on secondary incidents. Furthermore, the Hampton Roads RCTO work resulted in a research study on secondary incidents conducted by the Old Dominion University Transportation Program faculty.

The inclusion of the objective on secondary incidents indicates an operations philosophy that the Hampton Roads RCTO developers had with regard to strategic improvements. The developers valued reducing secondary incident occurrences to such an extent that they believed it was necessary to begin to work toward this objective even though the performance data was not yet in place. This is typical of the difficult decisions that the other RCTO demonstration site participants had to grapple with as well.

Creating an Approach

Upon reaching agreement on the RCTO operations objectives, the demonstration site RCTO development teams began to define how the objectives would be achieved. The approach and the elements of relationships/procedures, physical improvements, and resource arrangements specify how the collaborating participants will reach their desired operations objectives. The demonstration sites faced additional challenges as they worked to decide on the most effective operations strategies to employ, obtain commitment for specific actions, and identify available resources. Below are recommendations stemming from the experiences of the demonstration sites in building their approaches to an RCTO.

Gather Expert Practitioners in the Operations Area to Discuss and Recommend Actions

After developing a draft set of operations objectives around traffic incident management within a defined scope, the Hampton Roads RCTO development group hosted a one-day workshop to obtain a comprehensive picture of what actions were most needed by the traffic incident management practitioners to address the objectives. The workshop drew approximately 80 expert practitioners from police, fire, transportation, EMS, medical examiner, environmental quality, department of motor vehicles, tunnel and bridge authorities, emergency dispatch, towing, and other fields. The operations objectives were presented along with the idea of the RCTO, and then the practitioners were divided into breakout groups where they were led by facilitators to discuss where the deficiencies are in TIM and what needs to improve to reach the objectives. The RCTO development group gathered a variety of perspectives and got input on the most important improvements from the TIM stakeholders. With so many TIM players at the table, the stakeholders had the opportunity to determine how they could be better coordinated in the field and discuss this with their counterparts in the other agencies. The workshop resulted in a series of action items to be selected from for the RCTO. This included items such as "develop regional MOU template for communications between the TMC and fire operations" and "research method of having cell phone calls from Interstates route to Virginia State Police dispatchers."34

Provide a Menu of Options for Senior Decisionmakers to Select From

The approach for the Portland RCTO was formed using a menu of options that a team of agency leaders selected from. The staff-level RCTO development group members compiled a set of recommended options for their agency leaders to choose from to form the activities to be pursued for improved traffic incident management. The Portland RCTO led the staff group in organizing ideas for reaching the operations objectives by the phases of traffic incident management (detect, verify, respond, clear, recover) and a revised RCTO framework including procedures/protocol, policy/legal, and physical/capital improvements. The ideas were put into a table and the group engaged in a thorough discussion of which strategies would be most effective in the short, medium, and long term. During these discussions, the group worked to decide what aspects of the complex incident management issue should be tackled first. The menu was then given to the senior-level, multi-agency operations steering team to select from and direct their staff to pursue.

Do Not Develop a Wish List – Make Your Approach Realistic Based on Likely Commitment and Resources

With all of the ideas that practitioners may have for reaching the operations objectives, it is tempting to include more to be done in the RCTO approach than can be realistically accomplished given the commitment and resources available. For example, during the Hampton Roads RCTO one-day workshop with expert practitioners, multiple actions such as "keep oversized loads off of the roadways during rush hours" were proposed. While this was thought likely to help relieve traffic delays given the experience of the individuals in the group, it was not included in the RCTO because they did not have a commitment from the necessary parties to make those changes.

In Portland, the RCTO team developed an RCTO with an early emphasis on improving towing to work toward the incident management objectives. Towing held a prominent role because it was seen as an element of incident management where improvements could have a significant impact on the ability to reach the overall goal of reducing unnecessary delay associated with minor incidents. Portland also had political support to focus on this topic, the ability to collect data and measure performance related to towing, and it appeared to be an area ripe for early success. Additionally, the team had the participation of area towing officials and industry representatives.

Develop an Approach Sensitive to Participating Agencies' Needs to Maintain Control over their Operations

One of the most common challenges among regional transportation operations efforts is balancing agency control with a collaborative effort. The approach developed for reaching the operations objectives should reflect the participating agencies' desires to maintain control over their operations. In regions where a strong sense of trust has developed over time between agencies, the participating agencies may choose to allow consolidated operations, equipment sharing, and other joint management of transportation systems by establishing the necessary agreements.

The Tucson RCTO development group worked to develop an approach for improving regional traffic signal operations that would take advantage of the cooperative spirit among signal operators in the region while still maintaining the control desired by the individual agencies. The RCTO development group formulated two options to select from for a new regional traffic signal operations program. One option created a jointly funded regional traffic signal operations consortium with an oversight committee comprising representatives from the participating signal operations agencies. The consortium would have staff members dedicated to controlling, monitoring, and optimizing the traffic signals in the region, although signal maintenance would still be covered by the signal owning agency. The second alternative developed by the RCTO group proposed to retain consultant services to support the local jurisdictions in actively operating and managing their respective traffic signal systems. The second option for the regional traffic signal operations program was selected to reflect the preference of local agencies to have a greater degree of control over their systems. Creating options that incorporated the preferences and needs of local agencies for more jurisdictional control helped to advance a program with regional operations benefits.

Defining the Supporting Elements of the Approach – Relationships and Procedures, Resource Arrangement, and Physical Improvements

Build a Structure of Champions

Within each of Tucson's action plans, where feasible, a structure of champions was identified to guide the implementation of the plan. As an example, the PAG Transportation Systems Subcommittee was identified to champion the Regional Traffic Signal Operations Program with oversight on the program's focus areas, implementation, and funding. The subcommittee will be guided by PAG staff and will seek to establish a working group to guide program activities and make recommendations on the direction for consultant services and project selection. The existing PAG Transportation Planning Committee, comprising agency department heads in the region, would approve policies for the signal program and facilitate any necessary intergovernmental agreements. While actual signal timing plans will not be developed by PAG staff nor the subcommittee, staff and the working group will be responsible for overseeing the administration of the program and working both to elevate the issue within the regional transportation community and to facilitate the allocation of resources to develop and update signal timing plans. PAG staff or an identified individual from the working group will update the Transportation Systems Subcommittee, perhaps on a bi-monthly basis, concerning recent activities relating to the action plan.

Gain Commitment from Participants for Actions and Specify Roles and Responsibilities

The successful implementation of an RCTO depends on the commitment of participants to fill specific roles and take on well-defined responsibilities. Through developing an RCTO, the roles and responsibilities are documented as part of the RCTO. This represented a significant challenge for many of the RCTO demonstration sites. In an area where the political will for making improvements was high, such as Portland, agencies took on additional responsibilities, such as helping to draft new policies and develop multi-disciplinary training videos. Tucson was particularly effective in defining roles and responsibilities among collaborative partners and the existing PAG Transportation Systems Subcommittee. The RCTO from Tucson shows a table with specific action items to reach their operations objectives and an associated agency or organization responsible for championing that item.

| Action Item | Comments | Responsibility | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Update Tucson region maps on AZ511.com | Improve the Tucson area maps within HCRS to be commensurate with the ½ mile grid system. | ADOT | |

| Display Tucson region data on AZ511.com | Completion of this task is contingent upon import of TransView events into AZ511 (in IEEE1512 format). | ADOT in cooperation with TransView | |

| Import TransView events into AZ511. | TransView has the Tucson Police Department (TPD) and Pima County Sheriff's Department (PCSD) incident dataset available in XML but not in IEEE 1512 format. Convert XML data set into IEEE 1512 format (portion of the standard) for import to AZ511. |

TransView |

Estimate Resource Needs and Identify Realistic Options for Meeting those Needs

Most of the activities identified in an RCTO will require some kind of resource to accomplish whether it is staff time, equipment, or funding. Estimating the resource needs for the RCTO approach and identifying likely sources is a crucial element for building an RCTO that can be successfully implemented. During the development of the PAG RCTO, the developers identified the required resources and estimated costs for each of their RCTO actions. The example below shows the projects, capital improvements, and human resources/staff needed for putting in place a regional arterial dynamic message sign program. The PAG RCTO developers use the term "capital improvements" to indicate the physical improvements needed for the RCTO.