Planned Special Events: Cost Management and Cost Recovery Primer

Chapter 2: Basic Principles of Cost Management and Recovery

Cost management is the effective, overarching control of an organization's finances across multiple stages (add citation). Such financial control is only possible with a comprehensive understanding of an organization's service provisions:

- What services are provided?

- Who benefits from these services?

- What is the cost to the organization of providing these services?

Cost management is an organizational responsibility and an integral element of general management; good management implies good cost management. Cost management may include a policy of full cost recovery, partial cost recovery, or none at all. Whether or not an organization engages in cost recovery for a particular service is dependent upon many considerations, including the organization's mission, its traditional role, its legal responsibilities, and whether the service benefits the entire community.

Cost Management

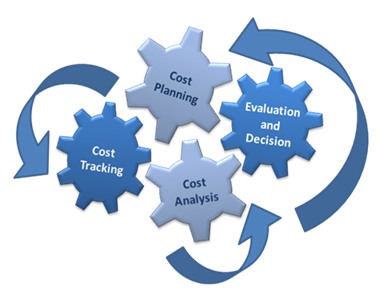

Cost management allows us to view the cost-benefit relationship of various activities, setting the stage for more informed decisions. Cost management generally begins with an initial planning of costs, continues through cost tracking and analysis of the information collected, and includes evaluations and decisions based on information from the previous stages. There is no set blueprint for a cost management system, and these stages may be organized differently to meet different organizational needs.

The four distinct stages described above are depicted in Exhibit 2.1. All of the stages are interdependent and decisions in any stage will affect the system as a whole. The system is a closed loop, so the last stage leads back to the first stage. The four stages are:

Cost Planning: Includes activities such as cost estimating, forecasting, and budgeting.

Cost Tracking: Includes discrete coding of activities and their associated costs, such as personnel time sheets, expense accumulation, and the use of financial systems.

Cost Analysis: Includes reporting on actual costs incurred and an analysis of these costs.

Evaluation and Decision: Includes evaluation of the costs with process changes implemented as necessary, regular consideration of shifting funding sources and options, assessment of current asset management and resource utilization, and decision-making regarding cost recovery.

Exhibit 2.1 A Cost Management System

The Elements of a Cost Management System

Cost estimating, forecasting, and budgeting are a part of cost planning. Cost planning is the projection of future costs. Cost tracking is backward-looking: it is accounting for what has already occurred. Cost tracking refers to following the cost of various activities through the cost management system and is accomplished through the use of discrete coding of activities and their associated costs. "Discrete coding" refers to tracking time and expenses related to specific activities. It includes methods such as time collection (the use of personnel time sheets) and expense accumulation. This type of data collection associates costs and activities for the various services being performed, enabling accurate analysis and optimal decision-making. While every stage of the cost management system is important, cost tracking is one of the most critical stages, because weaknesses in data collection will have the most detrimental effect on the other stages. Inaccurate data will lead to poor decisions and poor planning.

While different cost management systems may include different components, the indispensable element is an overall understanding of the interrelationship between activities and costs as well as the ability to manage these cost relationships to an organization's advantage. |

The analysis stage considers individual costs and related activities, while the decision stage evaluates the entire cost management system and provides an opportunity to make appropriate changes and institutionalize best practices. This comprehensive evaluation offers an opportunity to improve the system as a whole.

Evaluation and process changes (if necessary) should occur after every major event. Research conducted by the Federal Highway Administration in 2006 found that while some dialogue did occur following large special events, there was rarely a formal review process in place: "Even agencies that regularly conduct an after action assessment after major events do not use them as a source of reference for programmatic improvements." The author of that research noted that "after action assessment is critical for effective cost management. It also is important when justifying costs and revenues and demonstrating the value of a department's services to customers and the public."1

Asset management is central to the idea of cost management and includes the ability to show how, when, and why resources were committed. Through a comprehensive review of the entire portfolio of resources available, asset management leads to an improved understanding of how investment can effectively be used in achieving system-wide agency goals at optimal cost benefit. The Asset Management Primer published in December 1999 by the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration's Office of Asset Management is an excellent resource for additional information about this topic.2

The related concept of resource utilization is especially applicable to planned special events, because many changes can be implemented with relative ease. The City of Seattle found several methods of reducing costs through optimal resource utilization. The city relocated fun runs from city streets to city parks and chose to use alternate or shorter routes for parades. Both of these changes significantly reduced the cost of DOT and police traffic and crowd control services, reducing Police Department overtime expenses by 40 percent over two years. The Seattle DOT further reduced overtime expenses by varying the setup and tear-down times for certain events to coincide with regular work hours and by requiring event organizers to provide the labor and materials for signage along roadways. These methods are detailed in a 2008 study from the City Auditor.3

Keeping a cost management system effective is an ongoing process that requires continuous review and improvement of each of the elements of the system. Similarly, a cost management policy can only be as effective as its reach: it must be disseminated throughout the organization. Cost management is therefore a part of everyone's job. Public officials need to understand what cost management means, what their role is in practicing cost management, and how to implement their organization's policies.

While different cost management systems may include different components, the indispensable element is an overall understanding of the interrelationship between activities and costs as well as the ability to manage these cost relationships to an organization's advantage.

Identifying Costs

Identification of costs is a critical element throughout the cost management process. Identifying costs begins with understanding some the various types of costs, such as: fixed costs, variable costs, mixed costs, direct costs, and indirect costs.

Fixed costs are costs that typically do not change (in total) in response to changes in volume of activity. Examples include depreciation, supervisory salaries, and maintenance expenses. Variable costs are costs that change (in total) in response to the changes in the volume of activity. It is generally assumed that the relationship between variable costs and activity is proportional. For example, if the volume of activity increases by 10%, then variable costs in total will rise by 10%. Examples include the consumption of direct labor, direct materials, and direct expenses. Mixed costs are costs that contain both a variable cost element and a fixed cost element. These costs are sometimes referred to as semi-variable costs. One example is a vehicle rental that is billed at a base rate plus a per-mile charge. Direct costs are costs that easily can be linked to a specific service, activity, or department. Indirect costs are costs that cannot easily be linked to a single specific service, activity, or department.

Costs can also be broken down among labor, material, and overhead, each of which may be either a direct or indirect cost as well as a fixed, variable, or mixed cost. Labor, material, and direct overhead costs account for the majority of costs in many organizations. These costs are often easily traceable to specific activities and provide reasonably accurate cost information for cost management systems.

The allocation of indirect overhead is often more complex, since overhead costs can be used by many activities and costs can be driven by the sub-activities that support many final activities. For example, the cost of maintaining traffic barriers (painting, storing, etc.) is not directly related to a specific event. Maintenance costs are incurred regardless of whether or not the barriers are used in any specific event, and in fact the barriers themselves may be utilized for other activities, such as normal traffic control. The cost associated with this maintenance should be allocated against all barriers as an overhead allocation in such a fashion as to ensure that all users receive their fair and equitable share of the cost of this activity. Thus the first allocation would be to assign the cost of maintenance of the barriers and then allocate the cost of the barriers to the event using them. If, as an example, the barriers were required to be painted a specific color for a specific event, then the cost of painting them and consequently repainting them to their original color would appropriately be a cost of the special event requesting them and not part of the general allocation of maintenance costs.

Since the potential for cost recovery is an important element of cost management, it is helpful to follow a consistent and reliable approach which will ensure maximum cost recoverability. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget Circular A-87 establishes clear standards for distinguishing between various types of costs.4 While these principles are designed for use with federal awards (such as grants or cost reimbursement contracts), they can be incorporated into any cost management system. Adopting the principles of Circular A-87 will create a uniform cost management approach that is useful in all instances of cost recovery, since recoverability under this thorough approach will recover costs under almost any circumstance.

The circular defines direct costs as "those that can be identified specifically with a particular final cost objective" and provides the following examples of direct costs:

- Compensation of employees for the time identified and devoted specifically to the performance of those awards.

- Cost of materials acquired, consumed, or expended specifically for the purpose of those awards.

- Equipment and other approved capital expenditures.

- Travel expenses incurred specifically to carry out the award.

- Minor items. Any direct cost of a minor amount may be treated as an indirect cost for reasons of practicality where such accounting treatment for that item of cost is consistently applied to all cost objectives.

|

Exhibit 2.2

One best practice for allocating indirect costs is the concept of activity-based costing. In activity-based costing, resources consumed are allocated to the relevant cost objective based upon the activities being performed. Here is a simple, step-by-step approach to applying the activity-based costing concept:

|

Circular A-87 defines indirect costs as "those: (a) incurred for a common or joint purpose benefiting more than one cost objective, and (b) not readily assignable to the cost objectives specifically benefited, without effort disproportionate to the results achieved... [It] applies to costs of this type originating in the grantee department, as well as those incurred by other departments in supplying goods, services, and facilities." Examples of typical indirect costs that can be assigned to planned special events include certain central service costs of the organization, such as personal computers, accounting and personnel services, purchasing services, depreciation or use allowances on buildings and equipment, and the costs of maintaining facilities and equipment. The allocation of these indirect costs on a pro rata basis to all activities performed within the grantee department will provide for a more reasonable and equitable costing of the planned special event.

Establishing a number of pools of indirect costs within a department may facilitate equitable distribution of indirect expenses. These indirect cost pools are distributed to benefited cost objectives on bases that will produce an equitable result in consideration of relative benefits derived.

Understanding the cost driver, the key activity that drives the cost, is necessary for both cost management and cost recovery purposes. The cost driver is the activity that has the greatest correlation with actual cost. It is the best indicator of cost, although it most likely will not account for the total cost of a service. For example, for a street closure requiring the placement of barriers, the cost driver may be the number of miles along which barriers need to be placed, the number of personnel needed to install the barriers, the number of barriers used, or another related activity.

Since a cost management system derives its information from the overall financial accounting system, the maintenance of a highly reliable, accurate, and timely financial accounting system is important. The financial accounting system should be easily understood, well maintained, and documented. Properly trained personnel who understand and adhere to the requirement for discrete coding of activities and costs will help ensure the integrity of the process. Practicing such a continuous improvement approach will not only keep the cost management system effective, but will require considerably less effort than large-scale but less frequent updates.

Cost Recovery

Cost recovery activities are optional: an organization may choose to absorb all costs associated with planned special events. However, regardless of the extent to which an organization engages in cost recovery, it is beneficial for each organization to have a well-defined cost recovery policy. Having such a policy will facilitate financial control, ensure an equitable fee structure, and distinguish an organization's core programs and services from additional offerings.5

Cost recovery decisions begin with a mission statement that provides a clear definition of a department's organizational values and purpose. |

Some departments may consider it part of their mission to provide special event services to the general public at no charge. Other departments may not wish to achieve 100 percent cost recovery. Cost recovery decisions begin with a mission statement that provides a clear definition of a department's organizational values and purpose.

Deciding What Costs to Recover

There are many issues to consider when determining what percentage of expenses should be recovered. One consideration is whether the services provided for the special event will benefit the community as a whole or provide individual benefit to a small or specialized group. The distribution of benefits from a public service can be viewed as a continuum stretching in two directions, as pictured in Exhibit 2.3.

Exhibit 2.3

In general, the organization may choose not to recover costs for activities that are seen as benefiting the community as a whole and fulfilling the organization's mission. These services and programs may "increase property values, provide safety, address social needs, and enhance quality of life for residents" (Greenplay LLC, 2003). These are usually covered by taxes -they benefit the entire community and therefore the entire community pays for them. For events of this nature, a minimal fee, rather than partial or full cost recovery, may be appropriate.

Those activities that are considered highly individual are those which fall outside the core mission and may be priced to recover full cost plus a designated profit percentage.

In deciding a level of cost recovery, the organization may also wish to consider to whom they provide services and whether this constituency targets certain populations, such as children and families, local residents, county residents, regional residents, or non residents of the community. Additional questions to consider include:

- What is the effect of the event on the resources generally offered by the organization? What is the effect to others? Events may be classified as Low Effect to Resources or Other People, High Effect to Resources or Other People, or Exceed Dept/Personnel Capacity.

- Is it the organization's role to provide such services? Are such services legally mandated? The answer to this can range from a legal obligation to provide (such as to comply with ADA legislation), something the organization is traditionally expected to do, something the organization chooses to undertake because there is no other way to provide it, or something the organization should consider not providing as it is already being provided.

- Does the event provide marketing opportunities for the department or a chance to highlight the department's work and the ways in which it serves the community?

- Is cost recovery politically palatable? Some decisions may be based in part on politics, with the department having little input.6

In considering the appropriateness of cost recovery, a few special considerations pertaining to planned special events should be thought through:

- Treatment of events relating to free speech and the right of freedom to assemble

- Treatment of events held by non-profit organizations

- Treatment of events held by small organizations

- Indirect benefits and increased city revenue

For demonstrations and other time-sensitive assemblies that may occur in response to current events, a permitting process that requires applications to be submitted far in advance would not be appropriate. Departments must consider how to facilitate ease and speed in the permitting process for such events. Departments also may not wish to cost recover for these events, as that could cause an equity concern and limit the right of freedom to assemble for groups that may not be able to afford the fees.

Events held by small organizations lacking funding pose a similar equity dilemma. However, good cost management, can mitigate this issue as cost recovery will reflect the small share of resources used, and small groups will likely be able to afford the amount of resources they have used. Departments may nonetheless wish to waive or reduce fees based on the organization's budget or operating expenses and ability to pay applicable fees. Historically, many departments waive or reduce fees for events organized by non-profit groups. These events may bring the city positive publicity or help a certain segment of the city population.

Departments may choose not to engage in cost recovery if indirect benefits associated with the event are realized. The city often benefits from large events due to positive publicity and revenue from consumer demand associated with the event: taxes on merchandise, tickets, and hotel rooms. These events provide a draw for area residents and may make the city a more attractive place to live and work. In fact, cities often compete to stage large events. Charging full price for such events may cause events to relocate or scale-down, and thus may not be an appropriate choice for the city.

The basic principles for engaging in successful, equitable cost recovery efforts are summarized in Exhibit 2.4. These important best practices suggest the need to: implement cost recovery only where it is cost-effective, employ activity-based costing whenever it is appropriate, and conduct frequent process reviews.

|

Exhibit 2.4 Cost Recovery Best Practices

|

Conclusions

Good cost management is an integral part of good management and an organizational and individual responsibility. Cost management is an ongoing and interrelated process that requires frequent review to continue functioning successfully. Organizations should develop cost recovery policies, but may choose when and if to engage in cost recovery activities.

1 Kuehn, D. (2006). Managing Costs for Planned Special Events. Prepared for the 2nd National Conference on Managing Travel for Planned Special Events. Federal Highway Administration.

2 U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Office of Asset Management. (1999). Asset Management Primer. Available at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/asstmgmt/amprimer.pdf

3 Office of City Auditor, City of Seattle . (2008). Seattle's Special Events Permitting Process: Successes and Opportunities. Available at: http://www.seattle.gov/audit/docs/Special%20Events%20Report%20FINAL1-31-08.pdf

4 U.S. Office of Management and Budget. (2004). Circular A-87. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars/a087/a87_2004.html

5 The ideas regarding cost recovery and individual vs. community benefit contained herein were developed by Greenplay LLC and are copyright 2003. Their report, "Cost Recovery Pyramid Methodology" is available at www.GreenPlayLLC.com. Information in this section specifically relevant to planned special events is, however, the sole work of the author.

6 The ideas regarding cost recovery and 'additional questions to consider' were developed by Greenplay LLC and are copyright 2003. Their report, "Cost Recovery Pyramid Methodology" is available at www.GreenPlayLLC.com. Information in this section specifically relevant to planned special events is, however, the sole work of the author.

You will need the Adobe Acrobat Reader to view the PDFs on this page.

You will need the Adobe Acrobat Reader to view the PDFs on this page.