Comprehensive Truck Size and Weight Limits Study - Highway Safety and Truck Crash Comparative Analysis Technical Report

Chapter 1: Introduction

Provisions in MAP-21, the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (P.L. 112-141), require the Secretary of Transportation, in consultation with each relevant State and other applicable Federal agencies, to commence a comprehensive truck size and weight limits study. Per the legislation:

The study shall—

(1) provide data on accident frequency and evaluate factors related to accident risk of vehicles that operate with size and weight limits that are in excess of the Federal law and regulations in each State that allows vehicles to operate with size and weight limits that are in excess of the Federal law and regulations, or to operate under a Federal exemption or grandfather right, in comparison to vehicles that do not operate in excess of Federal law and regulations (other than vehicles with exemptions or grandfather rights);[1]

(2) evaluate the impacts to the infrastructure in each State that allows a vehicle to operate with size and weight limits that are in excess of the Federal law and regulations, or to operate under a Federal exemption or grandfather right, in comparison to vehicles that do not operate in excess of Federal law and regulations (other than vehicles with exemptions or grandfather rights), including—

(A) The cost and benefits of the impacts in dollars;

(B) the percentage of trucks operating in excess of the Federal size and weight limits; and

(C) the ability of each State to recover the cost for the impacts, or the benefits incurred;

(3) evaluate the frequency of violations in excess of the Federal size and weight law and regulations, the cost of the enforcement of the law and regulations, and the effectiveness of the enforcement methods;

(4) assess the impacts that vehicles that operate with size and weight limits in excess of the Federal law and regulations, or that operate under a Federal exemption or grandfather right, in comparison to vehicles that do not operate in excess of Federal law and regulations (other than vehicles with exemptions or grandfather rights), have on bridges, including the impacts resulting from the number of bridge loadings;

(5) compare and contrast the potential safety and infrastructure impacts of the current Federal law and regulations regarding truck size and weight limits in relation to—

(A) six-axle and other alternative configurations of tractor-trailers; and

(B) where available, safety records of foreign nations with truck size and weight limits and tractor-trailer configurations that differ from the Federal law and regulations; and

(6) estimate—

(A) the extent to which freight would likely be diverted from other surface transportation modes to principal arterial routes and National Highway System intermodal connectors if alternative truck configuration is allowed to operate and the effect that any such diversion would have on other modes of transportation;

(B) the effect that any such diversion would have on public safety, infrastructure, cost responsibilities, fuel efficiency, freight transportation costs, and the environment;

(C) the effect on the transportation network of the United States that allowing alternative truck configuration to operate would have; and

(D) whether allowing alternative truck configuration to operate would result in an increase or decrease in the total number of trucks operating on principal arterial routes and National Highway System intermodal connectors; and

(7) identify all Federal rules and regulations impacted by changes in truck size and weight limits.

The key words in this legislation as they relate to safety in this directive are "differences in safety risks" and "potential safety …impacts" of "alternative (truck) configurations." The comparisons to be made are between trucks legally operating within and those operating in excess of Federal limits.

1.1 Goals of the Safety and Truck Crash Comparative Analysis

The US Department of Transportation (USDOT) study team responded to this directive by using three different methods for examining the safety of these alternative truck configurations –

- Crash-based comparative analyses,

- Analysis of vehicle stability and control, and

- Analysis of safety inspection and violations data.

These multiple approaches were designed to provide an understanding of the safety performance of the alternative truck configurations of interest, particularly when faced with uncertainties associated with the crash data. From the outset, it must be understood that the lack of vehicle weight information on crash reports inhibits a robust comparative analysis of the crash implications associated with the alternative configurations assessed in this Study. Further, limitations on the availability of Weigh-in-Motion (WIM) data, primarily to Interstate System roadways, inhibited the construction of adequate exposure data sets needed to assess the crash situations involving heavy trucks. For these reasons, the three method approach was designed and followed to complete a crash assessment for inclusion in the Study.

Each of the three approaches that are listed has its own advantages and limitations, but the overall intent was to design a framework that provides a broad picture of the potential safety implications of the scenarios assessed in this Study.

Concerning crash analysis in particular, Table 1 reveals examples of the broad range of gross vehicle weight (GVW) limits currently in place among the States. From a safety analysis point of view, this diversity in existing fleets is an advantageous situation. Conducting crash-based and violation-based analyses of different configurations requires these configurations to have operated on the Nation’s highways for a sufficient number of years to accumulate adequate exposure and adequate crash samples. The goal of the safety and truck crash comparative analysis is to take advantage of this diversity by developing measures of differences in safety for configurations that may be allowed to operate on more of the nation’s highways in the future.

An approach was constructed and followed to perform the assessment using, as much as possible, crash data reflecting actual operations on U.S. roads. The crash-based analyses were based on both police-reported crash data in State crash files, on crash information collected by trucking companies, and on truck exposure data developed from different sources. Significant emphasis was placed on analyzing crash data because they are “real-world data,” and thus the most valid in nature. Acknowledged leaders in the transportation safety discipline have stated in several publications on the topic that analyzing data on injuries and fatalities is, in fact, the definition of “safety analysis” (AASHTO, 2010; TRB, 2011).

Note: Vehicles are allowed on at least some Interstate roadways.

Source: Information collected through State interviews with commercial vehicle safety program personnel.

Truck safety studies that depend on crash analyses present several specific challenges. Problems exist in defining specific truck configurations based on data available on police crash report forms. Because of limited VMT, and thus low exposure, there are small samples of crashes for some truck configuration of interest (specifically for triple-trailer configurations). The development of accurate truck travel estimates by configuration type and roadway type is difficult. Representative crash analysis results for the nation could not be developed for this Study due to these data limitations. Vehicle stability and control software allows a user to analyze specific maneuvers at specific weights and speeds for specific truck configurations; however, there is difficulty in determining the prevalence of these specific combinations of maneuver, weight, and speed by configuration in actual operations. Truck safety inspections and violation data does enable researchers to explore differences in safety-related violations between specific alternative and control configurations, and differences found in violation rates cannot be readily converted into predicted differences in crash rates. However, even with their limitations, each method provides important information on truck safety, and the combination of findings from all three, particularly to the extent that they are in alignment, provides even more validity to the results.

1.2 Current Truck Size and Weight Limits in the United States

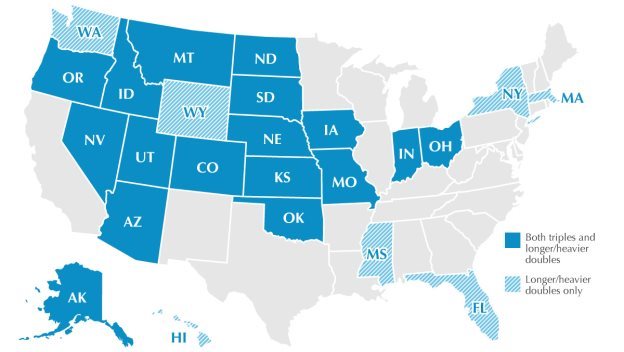

The MAP-21 directive notes that safety comparisons are to be made between trucks legally operating within and those operating in excess of current Federal limits. At first glance, this would imply that the comparisons are between “legal trucks” (including those operating with a valid State-issued overweight permit) and “illegal trucks” (i.e., overweight and oversize trucks operating without a valid permit). The current Federal gross vehicle weight (GVW) limit for five-axle tractors semitrailers and for five-axle tractors with twin semitrailers is 80,000 lbs. on the Interstate system. Current restrictions on trailer length allow a tractor to pull a 48-ft. semitrailer while travelling on the National Network, although a number of States allow the operation of tractor pulling a 53-ft semitrailer, which is considered the industry standard length. A twin-trailer configuration (i.e., a tractor and two 28.5-ft. “pups”) with a gross weight of 80,000 lb. or less is allowed on the National Network. However, there are numerous highways where trucks that are in excess of these Federal limits are legally operating due to exemptions found in Federal regulations and grandfathered State limits. Table 1 above provides examples of States allowing a tractor/semitrailer to operate above the 80,000-lb. limit. Longer combination vehicles (LCV), including triple-trailer configurations and double-trailer configurations heavier and longer than twins, operate in 17 States, mostly in the mid-western and western parts of the country (see Figure 1). The maximum GVW limits for these LCVs vary by State, but all exceed the 80,000-lb. Federal limit.

Figure 1: States Allowing the Operation of Longer Combination Vehicles (LCVs) on Some Portion of their Interstate System

Source: Title 23 Code of Federal Regulations, Part 658, Appendix C

Given the large diversity of configurations operating now, one question that had to be addressed was how to assess the impacts of trucks operating at and below current Federal size and weight limits compared to trucks operating above those limits. Another question that had to be addressed was how to assess the impacts that national operation of vehicles at sizes and weights above the current limits would have on highway safety, crash rates, highway infrastructure, the delivery of truck size and weight enforcement, the operation of other modes in the movement of freight.

Another important question was which configurations to use in the study. The MAP-21 language does not specify study configurations specifically, only referring to “six-axle and other configurations.” As a result, using inputs from the public, trucking companies, truck experts, advocacy groups and a variety of other stakeholders, USDOT defined six alternative truck study scenarios as shown in Table 2. Each scenario includes an alternative truck configuration with the network it will operate on and the access assumptions off of that network.

| Scenario | Configuration | Depiction of Vehicle | # Trailers or Semi-trailers | # Axles | Gross Vehicle Weight (pounds) |

Roadway Networks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Single | 5-axle vehicle tractor,53 foot semitrailer (3-S2) | 1 | 5 | 80,000 | STAA 1 vehicle; has broad mobility rights on entire Interstate System and National Network including a significant portion of the NHS | |

| 1 | 5-axle vehicle tractor, 53 foot semitrailer (3-S2) | 1 | 5 | 88,000 | Same as Above | |

| 2 | 6-axle vehicle tractor, 53 foot semitrailer (3-S3) | 1 | 6 | 91,000 | Same as Above | |

| 3 | 6-axle vehicle tractor, 53 foot semitrailer (3-S3) | 1 | 6 | 97,000 | Same as Above | |

| Control Double | Tractor plus two 28 or 28 ½ foot trailers (2-S1-2) | 2 | 5 | 80,000 maximum allowable weight 71,700 actual weight used for analysis 2 | Same as Above | |

| 4 | Tractor plus twin 33 foot trailers (2-S1-2) | 2 | 5 | 80,000 | Same as Above | |

| 5 | Tractor plus three 28 or 28 ½ foot trailers (2-S1-2-2) | 3 | 7 | 105,500 | 74,500 mile roadway system made up of the Interstate System, approved routes in 17 Western States allowing triples under ISTEA Freeze and certain four-lane PAS roads on East Coast 3 | |

| 6 | Tractor plus three 28 or 28 ½ foot trailers (3-S2-2-2) | 3 | 9 | 129,000 | Same as Scenario 5 3 |

1 The STAA network is the National Network (NN) for the 3S-2 semitrailer (53 feet) with an 80,000-lb. maximum GVW and the 2-S1-2 semitrailer/trailer (28.5 feet) also with an 80,000 lbs. maximum GVW vehicles. The alternative truck configurations have the same access off the network as its control vehicle. Return to Footnote 1 Table 2

2 The 80,000 pound weight reflects the applicable Federal gross vehicle weight limit; a 71,700 gross vehicle weight was used in the study based on empirical findings generated through an inspection of the weigh-in-motion data used in the study. Return to Footnote 2 Table 2

3 The triple network is 74,454 miles, which includes the Interstate System, current Western States' triple network, and some four-lane highways (non-Interstate System) in the East. This network starts with the 2000 CTSW Study Triple Network and overlays the 2004 Western Uniformity Scenario Analysis, Triple Network in the Western States. There had been substantial stakeholder input on networks used in these previous USDOT studies and use of those provides a degree of consistency with the earlier studies. The triple configurations would have very limited access off this 74,454 mile network to reach terminals that are immediately adjacent to the triple network. It is assumed that the triple configurations would be used in LTL line-haul operations (terminal to terminal). The triple configurations would not have the same off network access as its control vehicle–2S-1-2, semitrailer/trailer (28.5 feet), 80,000 lbs. GVW. The 74,454 mile triple network includes: 23,993 mile network in the Western States (per the 2004 Western Uniformity Scenario Analysis, Triple Network), 50,461 miles in the Eastern States, and mileage in Western States that was not on the 2004 Western Uniformity Scenario Analysis, Triple Network but was in the 2000 CTSW Study, Triple Network (per the 2000 CTSW Study, Triple Network). Return to Footnote 3 Table 2

In general, each scenario's alternative truck configuration uses its respective control vehicle’s nationwide network and access rules with the exception of the triple truck configuration, which has a restricted network and access rules (see Table 2). The numbers and letter combinations for each configuration refer to the number of axles on the tractor followed by the number on the semitrailer, followed by the number of axles on each additional trailer. So the “triple” configuration in Scenario 6 (3-S2-2-2) has three axles on the tractor, two axles on the semitrailer and two axles on each of the two additional trailers.

Notice that the desired alternative vehicle weights in Table 2 do not match precisely to the weight limits currently operating in the United States, as shown in Table 1. This is one indication of the practical difficulties the study team faced in categorizing crash involvements with respect to weight limits. The configurations determined by USDOT and outlined in Table 2 imply a desired level of precision in comparisons of crash involvements by truck configuration and weight that could not be met solely by using available crash data. In order to address this, the study team found it necessary to develop computer simulations of vehicle stability and control descriptors and to analyze violations and citations from roadside truck inspections.

Table 2, column 3 identifies the control or reference vehicle to which each alternative truck configuration is compared. There are two control vehicles that do not exceed current limits (i.e., 3-S2, 80,000 lb. and Twin 28.5, 80,000 lb.). Alternative tractor/semitrailer configurations in Scenarios 1-3 are to be compared to the 3-S2, 80,000 lb. tractor/semitrailer and the alternative double trailer and triple-trailer configurations in Scenarios 4-6 are to be compared to the 2-S1-2, tractor/semitrailer/trailer (28.5’), 80,000 lb. “twins” configuration. Each of these configurations realize broad mobility privileges for travel on the National Network as defined in 23 CFR Part 658 Appendix A.

Analyses using crash and violation data cannot be conducted at all for two of the scenarios. Scenario 1 crash analyses cannot be conducted because there is no truck weight information in State crash data that would allow the separation of the five-axle, 88,000-lb. alternative configuration from the five-axle, 80,000-lb. control vehicle. In addition, the analysis of the Scenario 4 five-axle, 80,000-lb. configuration could not be conducted using crash or violations data since this configuration is not currently operating in the United States. However, both of these alternative truck configurations (and all four other alternative truck configurations) were analyzed in the vehicle stability and control analyses.

The remainder of this report provides details and findings of the three major safety analysis methods – (1) crash-based analyses, (2) analysis of vehicle stability and control through computer simulation, and (3) analysis of safety inspection and violations data.

[1] The Federal government began regulating truck size and weight in 1956 when the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act (Public Law 84-627), establishing the Interstate Highway System, was enacted. A state wishing to allow trucks with sizes and weights greater than the Federal limits was permitted to establish “grandfather” rights by submitting requests for exemption to the FHWA. During the 1960s and 1970s, most grandfather issues related to interpreting State laws in effect in 1956 were addressed, and so most grandfather rights have been in place for many decades. See USDOT Comprehensive Truck Size and Weight Study, Volume 2, “Chapter 2: Truck Size and Weight Limits – Evolution and Context,” FHWA-PL-00-029 (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2000), p. II-9. Return to Footnote 1