Report On The Value Pricing Pilot Program Through May 2009Printable Version (PDF 688KB) September 17, 2009U.S. Department of Transportation

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Project Type | Projects Implemented | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Pricing Involving Tolls | ||

| HOT Lanes (Partial Facility Pricing) | Seven HOT lane projects have been implemented under the VPPP since 1995 and are operating successfully in six States. They include on I-15 in San Diego, on I-25 in Denver, on I-95 in Miami, on I-394 in Minnesota, on I-10 and US 290 in Houston, and on SR 167 in Seattle. (Note: Only one other HOT lane project is operational, on I-15 in Salt Lake City.) | The VPPP has funded over two dozen studies involving HOT lanes or express toll lanes, including pre-implementation and outreach efforts. |

| Express Toll Lanes (Partial Facility Pricing) | One project, on SR 91, is operating successfully in Orange County, California. Denver/ 2006 | The VPPP has funded an evaluation study of the SR 91 express lanes and over two dozen studies involving HOT lanes or express toll lanes, including pre-implementation and outreach efforts. |

| Pricing on Entire Roadway Facilities | Four projects are operating in three States. These include higher peak period tolls on the San Joaquin Hills Toll Road in Orange County, California; on two bridges in Lee County, Florida; on the New Jersey Turnpike in New Jersey; and on the Interstate toll crossings between New York and New Jersey operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. | A dozen studies have been funded by the VPPP, including pre-implementation studies and evaluation studies of operating facilities. |

| Zone-Based Pricing | None | Only one study has been funded. |

| Regionwide Pricing | None | The VPPP has funded a dozen studies by States and metropolitan planning organizations. |

| Pricing Not Involving Tolls | ||

| Making Vehicle Use Costs Variable | One carsharing project is operating in San Francisco. | Half a dozen studies have been funded. |

| Parking Pricing and Other Market-Based Strategies | Two projects have been implemented in Seattle: a parking cash-out project and a "cash-out of cars" project. | Half a dozen studies have been funded. |

In order to encourage broader and bolder applications of value pricing, in December 2006, the Department solicited applications for the VPPP under a joint solicitation with the ITS Program and a new "Urban Partnership Agreements" (UPA) program established by the Department. The solicitation encouraged applications with a short-term time frame for implementation of broad-scale congestion pricing. The grants included VPPP grants as well as other discretionary grants, and were awarded under the Department's UPA program and its successor Congestion Reduction Demonstration (CRD) program. Appendix 6 provides a brief description of the UPA/CRD projects underway in six cities. By far, the largest research effort underway in support of the VPPP is a comprehensive evaluation of the impacts of congestion pricing projects in the six cities awarded discretionary grants for the purpose of demonstrating synergistic combinations of congestion pricing with supporting strategies involving transit, technology and travel demand management.

A second solicitation was issued for the VPPP in September 2008 for grants using FY 2009 funds. The solicitation focused on studies of regionwide congestion pricing and implementation of projects not involving tolls.

In March and April 2007, the Department conducted a national Webcast and regional workshops in Washington, DC, Denver, and Atlanta to promote congestion pricing and encourage applications through the UPA solicitation. Additional outreach activities were conducted through participation in Road Pricing Workshops sponsored by the Transportation Research Board; through congestion pricing webinars sponsored by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA); and through DOT participation in workshops and meetings sponsored by other stakeholder organizations.

A series of Congestion Pricing Primers and one-page briefs have been developed and widely disseminated, including posting on FHWA's and DOT's Web sites. The FHWA web site additionally provides links to publications on congestion pricing produced by the Department, VPPP grant recipients, the Congressional Budget Office, the General Accountability Office, the Transportation Research Board, universities, and other research organizations. A suite of analytical tools is also available on FHWA's web site to assist in estimating the impacts and assessing costs and benefits of pricing strategies. Several research projects on congestion pricing have been completed or are underway by the Office of the Secretary, FHWA and the Research and Innovative Technology Administration, and are listed in Appendix 7.

In this section we summarize the impacts from a sampling of the various types of pricing projects that have become operational in the U.S. Appendix 8 presents similar information for international projects. This section draws on findings from an FHWA research report prepared to support the program, "Value Pricing Pilot Program: Lessons Learned" (K.T. Analytics and Cambridge Systematics Inc. 2008). Appendix 8 draws from a companion FHWA report, "Lessons Learned from International Experience in Congestion Pricing" (K.T. Analytics. 2008).

HOT Lanes: On San Diego's I-15 reversible HOT lanes, the total number of vehicles using the previously underutilized lanes increased by 54 percent over the first 3 years of the HOT lane program. The time advantage of the express lanes has been maintained, in keeping with the requirement that free-flowing traffic conditions (i.e., Level of Service C) be maintained.

Express Lanes: The SR-91 Express Lanes provide congestion free, high speed travel at 60-65 mph to paying customers during peak periods, while the traffic on adjacent free lanes crawls under heavily congested stop-and-go conditions averaging no more than 15-20 mph. The use of the Express Lanes has continued to grow over time, without reducing traffic speeds.

Pricing on Toll Facilities: In 2001, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) initiated a variable toll program at the two tunnels and four bridges connecting New York City and New Jersey. Surveys of auto users and truck dispatchers indicate that 7.4 percent of passenger trips and 20.2 percent of truck trips changed in some way in response to time-of-day pricing. About 20 percent of auto users who changed their travel behavior in some way shifted to transit.

Making Vehicle Use Costs Variable: Pilot field tests of this approach have been carried out and evaluated in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Atlanta, Oregon, and Seattle. These experimental projects have shown that driver behavior changes significantly when drivers are made fully aware of the real costs of driving and given an opportunity to avoid some of these costs by changing their travel behavior.

Parking Pricing and Other Market-Based Strategies: King County, Washington, implemented a small parking cash-out demonstration project in downtown Seattle under the VPPP, where participating employers that offered their employees free parking also offered the option to receive cash in lieu of the parking space. Slightly over 10 percent of the employees offered cash-out, who previously drove to work, opted to accept the cash and leave their cars at home. A large-scale, on-street parking pricing project is being implemented in San Francisco involving on-street parking meter rates that vary to ensure some availability at all times, and early results will be available in 2010.

Most experience with priced lanes in the U.S. has been with underutilized HOV facilities being converted to HOT lanes. Such conversions allow some vehicles to shift from congested lanes, using the toll price to limit the degree of shifting and preserving the incentives for carpool and transit use. However, this form of pricing does not encourage increased transit use in and of itself through increasing the costs of auto use or improving transit operating conditions. One exception, on San Diego's I-15, transit ridership increased by 9 percent during the evaluation period, likely due to new bus service that was introduced in the corridor at the same time.

Experimental "making vehicle use costs variable" projects have shown some increases in transit use. In Portland, Oregon, 14 percent of households in a pilot test of rush-hour fees reported that a household member began using public transit to save money. In Seattle, findings from a pilot test of regionwide pricing using a sample of households indicated that nearly 80 percent of households drove less and/or shifted travel modes.

None of the projects implemented have measured any significant impact on air quality to date.

Since implemented variable toll projects have involved partial facility pricing or relatively small increases in peak period tolls, there have not been significant equity impacts. With an eye toward addressing equity issues that arise with broader pricing approaches, studies funded under the VPPP have explored innovative approaches to address equity issues:

Since most implemented U.S. projects to date have focused on partial facility pricing (primarily HOV to HOT conversions), they have generated limited revenues, sufficient only to cover costs for operation of the pricing program on existing lanes. However, the objective has been to manage demand on the priced lanes; generation of revenue has not been a goal. In San Diego, the FasTrak program on I-15 HOT lanes is fully funded with toll revenues, including operating and enforcement costs. Since 1998, the FasTrak program has generated over $7 million in surplus revenue, which has been used to fund express bus service in the I-15 corridor.

In Orange County, California, the 10-mile express toll facility in the median of SR 91 generates gross annual toll revenues of over $40 million. This amounts to about $1 million per lane mile annually. Revenues are used to pay for operations and maintenance, and for debt service for the facility. Excess revenues are proposed to be used for highway improvements in the corridor extending into Riverside County.

In 2006, the VPPP partnered with the Department's UPA program in order to encourage broader applications of congestion pricing. However, despite the over three-quarters of a billion dollars in grants offered by the Department through the competitive UPA program and its successor CRD program, only one project will implement performance-based pricing on all lanes of a highway facility. The rest are "partial" pricing projects involving priced lanes and one pricing project not involving tolls. While these approaches will be helpful in demonstrating innovative technical and policy approaches to facilitate and accelerate HOV to HOT conversions, they are not the more comprehensive pricing strategies initially contemplated either by the UPA/CRD programs or the VPPP. The Department is conducting a major evaluation effort involving all funded UPA and CRD projects. Early results from this effort will be available in 2010.

Underutilized HOV lanes are prime candidates for conversion to HOT lanes. However, there are limits to the number of underutilized HOV facilities, and some of these present operational challenges. The UPA competitive process demonstrated that there are ways to expand the opportunities for HOT lane implementation even when there might be physical capacity constraints. In Miami, new physical capacity has been created by re-striping the lanes on I-95. By making the lanes narrower and taking a portion of the shoulders, an additional lane has been created, to be priced along with the existing HOV lane which had been overutilized. Minneapolis will create a new HOT lane on a segment of I-35W by using a shoulder as a travel lane during peak hours. Los Angeles is creating an additional lane on I-10 by re-striping it and using a portion of the wide buffer between the existing HOV lane and the regular lanes. Both the new lane and the HOV lane will serve as HOT lanes. In Atlanta and Miami, additional capacity for use by priced single-occupant and HOV-2 vehicles is being "created" by increasing occupancy requirements for free service from 2+ persons per vehicle to 3+ persons per vehicle.

The only project proposing to toll all lanes on an existing toll-free facility is the SR 520 floating bridge in Seattle. This project has gained acceptance not because of its performance-based congestion pricing feature, but rather because the public and elected officials saw tolling as the only way to obtain the revenue needed to reconstruct the bridge. The variable tolling feature of the project resulted from Seattle's interest in securing a UPA award.

It is noted that Seattle's public and elected officials are far ahead of the rest of the country when it comes to understanding the benefits of variable tolls. Surveys have shown significant understanding and strong public support for variable tolls. To a large measure, this is due to a long history of public outreach and public involvement in the planning process, supported in part by VPPP grants to the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) as well as the Washington State DOT.

Like Seattle, many jurisdictions see congestion pricing first and foremost as a way to generate significant revenues. However, this support can be short-lived if congestion reduction is not part of the rationale for implementation of a pricing strategy.

The UPA program did learn important lessons from one UPA proposal that did not move forward to implementation – the proposal from New York City to introduce cordon pricing in Manhattan.

Mayor Bloomberg recognized that if New York City wanted to seriously address congestion, a major contributor to air pollution, congestion pricing was the only strategy that would have a significant impact. Prior to his announcement to move forward with congestion pricing on Earth Day in April 2007, Partnership for New York City, a business-led organization, had taken up the cause of congestion pricing and joined with a coalition of interest groups to build support for an UPA program proposal. An important aspect of Mayor Bloomberg's proposal was to dedicate net revenues from the congestion pricing program to fund capital improvements to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's transit system. A strong firewall was proposed in State legislation to ensure that net revenues were protected from diversions to other uses.

On March 31, 2008, the New York City Council, an elected body, voted to charge new fees for use of existing free roads for general use. While the project did not go forward as scheduled due to failure to obtain approval from the State's legislature, this vote broke new ground in the U.S. Up to this time, elected bodies in the U.S. had only supported new road use charges on motorists on new roads, new lanes, or existing lanes previously restricted to high-occupancy vehicles.

The proposal's success in the City Council was bolstered by the combination of a strong political champion (Mayor Bloomberg), significant congestion, support by a coalition of diverse interest groups, and an appealing plan for use of net revenues. A key factor was also the DOT funding incentive.

While there was much done right in New York, factors that could have contributed to its failure were:

The proposal from New York City demonstrated that bold and broad pricing approaches can be spurred by collaboration among multiple local agencies when the Department uses an integrated funding approach involving different modal administrations.

The purpose of the VPPP is to demonstrate to what extent roadway congestion may be reduced through application of congestion pricing strategies. However, as discussed previously, the projects implemented so far have not had significant impacts on congestion due to their limited scope, involving "partial" pricing of highway facilities.

There is no doubt broad congestion pricing could have more significant impacts on congestion with performance-based tolling of all lanes of entire highway facilities, entire zones or entire networks (see "Types of Congestion Pricing" in section II). However, such broad applications raise several issues, chiefly: fairness, equity for low-income individuals, traffic diversion, administrative costs and privacy.

Fairness: A primary reason for the success of partial facility pricing is that motorists want the choice of whether or not they pay for their use of roads. With a full facility or comprehensive congestion pricing scenario, some feel they would not have such a choice and would be forced off the roads they have always used for free. When congestion-free service is promised in exchange for the extra costs, many simply cannot conceive that highways could be free of congestion, despite admission by many that they would consider changing their schedule, mode, or route if this type of pricing were implemented.

When proposals are made to increase peak period toll rates on tollways, motorists worry that the system could be a financial burden that they can ill afford on top of current taxes. For example, a new peak period toll or toll increase of just 15 cents per mile amounts to an extra $3.00 for a 20-mile trip to work, $6.00 per day, and $1,500 per year.

There is some indication that the public might accept pricing on existing toll-free facilities if there is a credible and concurrent reduction in other taxes, or if the revenues will be dedicated to pay for transportation improvements that they are convinced are needed, as in the case of the New York City proposal and SR 520 in Seattle.

Focus group studies conducted under the VPPP have shown that the public does not understand how transportation is funded today. To gain public acceptance for pricing on existing roads, it will be important to explain to the public how transportation is currently funded, how any new system will affect households, how much more (or less) they will pay as a result, and what benefits will accrue to them in return.

Equity: With broad congestion pricing proposals, concerns about equity for low-income individuals relate to the ability of low-income motorists to pay the new charges.

Before use of revenues is considered, the benefits of broad-scale congestion pricing are not distributed equally among all users. High income users are more likely to remain on priced highways, paying the congestion fee and benefiting from a faster trip. Low-income users are worse off if they choose other less expensive times, routes or modes. If they stay on the priced highway, the value that they place on the faster trip may be less than the out-of-pocket cost to them. Some note that pricing is particularly unfair to commuters with less flexible work schedules, since they are unable to shift their time of travel. Low-income workers tend to have jobs with fixed schedules.

Another equity concern is that congestion pricing may make it too difficult or too expensive for low-skilled workers to get to their jobs. Entry-level and unskilled jobs are often not well-served by public transit. Even if transit routes provide service to jobs of this type, the work hours for such jobs often require travel during off-peak service times, when public transit is less frequent and less appealing as an option. Thus many low-skilled workers need to drive to hold on to their jobs. Note, however, that tolls would normally not be charged during off-peak periods with a congestion pricing approach that sets toll rates based on demand.

Despite the above concerns, a well-designed broad congestion pricing strategy can be less burdensome to low-income citizens with appropriate use of toll revenue. For example, when a portion of the toll revenue is dedicated to transit, low-income transit riders can benefit significantly from toll-financed transit improvements. Additionally, pricing schemes can include protections for low-income individuals, such as "life-line" credits or toll discounts with the amount of discount scaled based on income. In the case of the New York City cordon pricing proposal, the State legislature included tax rebates for low-income individuals for any fees paid that exceed the fare for a transit trip.

Traffic Diversion: With full facility pricing, if new or higher charges are established on only some roads (e.g., limited-access highways), some traffic is likely to divert to free routes, increasing congestion in neighborhoods.

The key to reducing diversion to alternative free routes is making improvements to quality, convenience and price of alternative modes. For example, bus service can be made more attractive through improvements in travel time, frequency of service (which reduces wait time), reductions in fares, improved parking availability at park-and-ride lots, and more comfortable rides. However, while this will increase the proportion of "tolled off" drivers who opt for transit, it will not completely eliminate diversion to alternative toll-free routes. Net diversion to free routes can only be avoided if the total cost of travel on the priced highway, comprising out-of-pocket cost as well as travel time and other non-monetary cost, is no higher than the total cost on the highway prior to introduction of pricing 2.

Studies completed for FHWA (The Louis Berger Group 2009, Noblis Inc. 2008) as well as the United Kingdom's Department for Transport (Department for Transport 2004) suggest that a relatively small reduction in existing traffic (of about 10 percent) can restore free-flowing traffic conditions on the highway system. This may be observed on Columbus Day, when a relatively small percentage of commuters are off work, or in August in Washington, DC, when Congress is not in session. This suggests that about 10 percent of solo-drivers on a newly priced highway would need to be "tolled off" a priced highway in conjunction with a congestion pricing strategy designed to significantly reduce highway congestion.

Handling a significant portion of former highway drivers may be possible on downtown-oriented transit systems, but is more difficult in corridors oriented to suburban employment centers. Paratransit could perhaps play a larger role. For example, private shuttle services operate successfully without public subsidy for travel to airport destinations not served by transit, because of the high costs to park at airports. High costs to drive on suburban highways during peak periods could potentially spur development of such private services oriented to employment centers. Vanpool services are also likely to increase ridership. Government support and encouragement of telework arrangements and flexible work schedules could provide additional options to commuters to avoid peak period travel altogether. Of the 10 percent of solo-drivers that would be tolled off a priced suburban highway, perhaps as much as 2 to 4 percent might opt for transit, paratransit, vanpooling, carpooling, telework, or flexible work schedules in order to avoid peak period charges. The remaining 6 to 8 percent (calculated by subtracting the 2 to 4 percent who might opt for alternatives from the 10 percent that would be tolled off) might choose to drive on alternative free routes.

Some increase in the capacity of the priced highway will be needed to accommodate these 6 to 8 percent of drivers (and keep congestion toll rates relatively low) if traffic diversion to free routes is to be avoided. Small increases in peak period highway capacity could potentially be achieved at relatively low cost by converting highway shoulders into "dynamic" travel lanes that could be used during peak periods in combination with active traffic management strategies (DeCorla-Souza 2009). Induced demand would be curbed using congestion pricing on all lanes of the actively managed facility. Pricing projects that incorporate active traffic management will begin operating in 2010 in Minneapolis and Seattle. They will provide valuable lessons about the feasibility and desirability of such approaches.

Administrative and Other Costs: Implementing and operating a congestion pricing scheme is expensive relative to other ways of generating revenue from highway users. Operating costs for congestion pricing are estimated to range from 10 to 20 cents per electronic transaction. If the average toll is 15 cents per mile, and the average length of tolled highway used per trip is 5 miles, the toll operator must spend about 20 percent of the revenue (i.e., 10 to 20 cents out of 75 cents) to collect the toll. By comparison, collection of fuel taxes costs about 1 percent of revenue.

Moreover, the above costs do not include enforcement costs. Revenues from penalties are generally sufficient to pay for these costs, but enforcement costs are an economic cost to society, paid by toll violators.

Congestion pricing is justified only if the value of benefits, such as those discussed in the next section, exceed the incremental costs for implementation and operation. Before a decision to proceed is made, synergistic combinations of congestion pricing and supporting strategies should be subjected to a comparative benefit-cost or cost-effectiveness evaluation along with other alternatives. The long-range transportation planning process could be used to educate the public about costs and benefits of alternative pricing approaches, and to begin the discussion about the trade-offs between conventional transportation investment approaches and approaches involving congestion pricing. For example, the five alternatives analyzed and presented for consideration by the public for the Year 2040 regional transportation plan for the Seattle area all involve substantial increases in road user fees beyond present practice (Puget Sound Regional Council 2009). The alternatives are compared to a base case that does not include pricing. One alternative essentially implements full pricing for all vehicles on all expressways and arterials, similar to PSRC's GPS-based charging trial funded under the VPPP.

Note that administrative costs will not be the only additional public costs for implementation of a comprehensive congestion pricing approach. In addition to making improvements to quality of transit service, its physical capacity will also need to be enhanced. Handling 10 percent of former highway drivers may be possible on downtown-oriented transit systems, and may not require a level of expansion of transit capacity that is impossible over a short time-frame. Yet, there would be high public cost burdens, both for new capital equipment as well as for operations. For example, a transit system that currently serves 20 percent of downtown workers may need to serve an additional 8 percent, requiring a 40 percent increase in transit service. A transit system that currently serves one percent of suburban workers may need to serve an additional 2 percent, requiring a 200 percent increase in transit service. Fortunately, future streams of congestion pricing revenues could be leveraged to pay up-front costs for new capital needs for transit rolling stock and park-and-ride facilities. Also, some of the transit operating cost burdens could be funded from the continuing stream of toll revenues.

Privacy: Some members of the public are concerned about the privacy impacts of the technology used to monitor road use and collect toll payments. With partial facility pricing, this has not been a major concern. Toll facility operators have reported that even when anonymous accounts have been offered to the public, there have been very few who have signed up. Singapore has alleviated privacy concerns by collecting tolls using smart cards with stored value that may be inserted into the in-vehicle equipment supporting the transponder. These "electronic purses" are replenishable at Automated Teller Machines (ATMs), and may also be used for other purchases unrelated to tolling.

Privacy does not appear to be a major concern with full pricing of only the limited access highway network using transponder-based toll collection technology. In a focus group study on such a strategy conducted by DOT (Volpe 2008), privacy was not an issue that resonated strongly or generated much discussion with most participants, perhaps because vehicle identification technology would be restricted to limited access highways only, and information on trip origins and destinations off the tolled system would not be collected.

However, privacy has been consistently raised as a concern when pricing has been proposed for implementation with use of in-vehicle units that would collect information on travel using GPS technology. Even when it has been made clear that information on the location of travel will never leave the vehicle, and only the total amount of toll charges will be sent to a "back-office" for billing and payment, some motorists have expressed concerns. They are uncomfortable with such information being available in their vehicles, and worry that it may be accessible to others at any time. Research currently underway through the National Cooperative Highway Research Program is exploring non-GPS technology that could potentially be used to collect ubiquitous user charges. These technologies may have fewer privacy concerns since specific location data would not be collected.

Despite the issues noted above, transportation policymakers are showing increasing interest in broad congestion pricing as a policy tool, because of the potential to achieve public goals more effectively than other conventional means. The benefits derived from congestion pricing include more efficient use of resources, generation of revenue for transportation investment, and support of economic productivity, environmental sustainability and livable communities.

Using Resources More Efficiently and Generating Revenue for Transportation Investment: The benefits that accrue to transportation system users and to society as a whole from the adoption of congestion pricing ultimately stem from the fact that it encourages people to use available resources more efficiently. In the absence of such mechanisms, the "market" for the use of the transportation system becomes distorted, leading to overuse of some portions of that system and underutilization of other elements. This inefficiency of use can in turn send distorted signals about where investment in transportation system capacity is particularly needed.

By its very nature, congestion pricing is also a means of generating revenue from highway users. The decision to implement congestion pricing is thus also a decision about the mix of funding sources (from both users and non-users) that are used to support the development and operation of the transportation system. By raising the out-of-pocket costs of highway travel to users, highway user charges tend to reduce the demand for use of the system. While user charges levied on a fixed rate per-mile or per-gallon basis do have an impact on traveler behavior, variable rate user charges with rates tied to the time of day or real-time congestion levels have the potential to have much larger impacts on peak-period travel.

Different forms of congestion pricing affect the efficiency of the transportation system in different ways. Implementing tolls on highways that vary by time of day or by the level of congestion on the facility encourage people to shift their time, route, or mode of travel to one that is less congested (or to forgo particularly low-valued trips altogether), thereby reducing congestion on the system as a whole. Pricing can also be used on new, express facilities to ensure that such facilities operate at maximum efficiency, providing a premium service for especially high-valued road trips (such as urgent travel or transit vehicles carrying large numbers of patrons).

Road pricing can also reduce congestion, significantly reducing the level of capital investment required to achieve a given level of operational performance on the highway system in a growing economy. Reduced traffic levels can also reduce the amount of wear and tear on our roads and thus the investment required to keep them in a state of good repair. This effect is particularly strong in large, heavily congested urban areas, where efficient pricing may obviate the need for some extremely expensive highway capacity improvements. For example, the average cost of construction to add a lane to an urban freeway is estimated at almost $15 million per lane mile. Weekday peak period use of this lane addition amounts to about 10,000 vehicles per weekday, translating to a cost of about 40 cents per mile driven by each peak period vehicle using the lane, or $8.00 for a 20-mile trip made on an added urban freeway lane during peak periods.

On the other hand, fuel taxes generated from a 20-mile trip amount to a total of only about 32 cents, assuming a vehicle fuel efficiency rating of 25 mpg. The reduced need for such expensive highway improvements can reduce the demand on scarce tax-based resources and free up resources to be used for investing in other forms of transportation or in other sectors of the economy. Under the investment scenarios analyzed in DOT's 2006 Status of the Nation's Highways, Bridges, and Transit: Investment and Performance report to Congress, the universal adoption of congestion pricing was projected to reduce annual highway investment requirements by 16 to 27 percent.

Congestion pricing also assists in keeping pace with growing travel demand over time, something that has been a constant challenge in recent decades. As congestion tolls increase in corridors with growing demand, this can provide a clear signal that transportation investment is needed in such locations. It can also provide a source of revenues to support such investment that is closely tied to the system users who will benefit from that investment. By pricing road use properly, the amount of additional travel that may be induced by capacity improvements can also be limited.

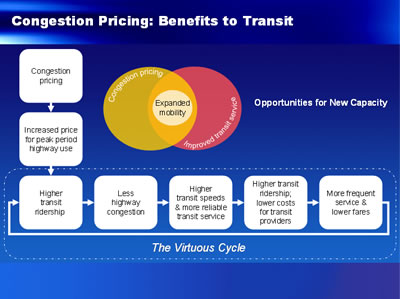

Congestion pricing and public transportation in particular can convey mutual benefits, with each supporting and reinforcing the effectiveness of the other. Congestion pricing reduces travel times for buses that currently operate on congested roadways. It can also provide a potential source of revenue to support transit. By supporting the development and operation of premium express transit facilities and services, pricing can also help improve the operating frequency, quality and reliability of public transportation, leading to increased public transportation ridership.

A high-quality public transportation system enhances congestion pricing by providing a viable alternative for serving commuters who decide to shift their mode of travel in light of higher charges for highway use in peak periods. This is particularly beneficial for commuters or others who may find it difficult to shift the timing of their trips, and can help limit the extent to which newly priced travelers may simply decide to divert their trips to other toll-free routes. A high-quality transit alternative can also address equity concerns by providing mobility to low-income travelers and by reducing the toll levels that would be necessary to reduce highway use by a certain amount. This relationship between road pricing and transit is sometimes referred to as "the virtuous cycle" (see the graphic below).

Economic Productivity: By addressing congestion through pricing, the overall productivity of the economy can be improved. Growing congestion and unreliability of travel times affects truck transportation productivity and ultimately the ability of sellers to deliver products to market. Additionally, when deliveries cannot be relied on to arrive on time, firms must keep additional "buffer stock" inventory on hand, increasing their cost of doing business and potentially affecting their competitiveness in international markets. While the business community would see some increased monetary costs as a result of a pricing scheme, there would be net savings in the total cost of doing business because the value of time and vehicle operating cost savings, and savings in costs for maintaining buffer stock would be significantly greater than the out-of-pocket cost for tolls.

Congestion also affects labor markets. Just as improvements in transportation technology over the last two centuries have allowed our urban centers of commerce to grow, increasing congestion has the opposite impact. This effectively reduces the size of the labor pool that firms are able to draw from, limiting their ability to attract employees with the best qualifications or most suitable skills. As a result, congestion can limit the productivity of these firms. By reducing congestion with broad-scale congestion pricing, business productivity can be increased.

Environmental Sustainability: Congestion pricing can reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions by encouraging use of alternative travel modes and by improving the flow of traffic.

Congestion pricing can also work in concert with other, more targeted measures aimed at reducing fuel consumption. Efficient pricing can help reduce the so-called "rebound effect" that can occur when vehicle owners respond to improved fuel economy by driving more. Congestion pricing can also enhance the effectiveness of pricing mechanisms aimed directly at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, such as carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems.

Livability: Congestion pricing can promote more livable communities by reducing traffic, noise and emissions of pollutants, encouraging development and use of transit, biking and walking as alternatives to driving, and reducing the need for additional highway capacity investment. For example, when congestion pricing reduced traffic in Central London, some freed-up roadway space was utilized to create bike lanes and bus-only lanes, further improving transportation alternatives.

Two of the most comprehensive and successful international examples of zone-based pricing have been in London and Stockholm. Their experiences demonstrate that properly structured zone-based charging schemes can reduce urban congestion, improve the environment, and increase public transportation ridership. More importantly, these examples demonstrate the significant relationship between the success of broad-scale congestion pricing and the provision of public transportation. In both cases, the government introduced major increases in transit service in advance of implementation of congestion pricing. In London, a significant portion of the revenue is used for continuing support of transit services. However, many States have constitutional or other legal provisions that would prevent money raised from tolling from going to non-road projects. Unless addressed, these prohibitions would limit the effectiveness of congestion pricing.

Based on project experience and three comprehensive reviews of public opinion studies on congestion pricing [Higgins (1997); Berg (2003); Zmud (2007)], some important summary lessons about the role of public opinion in project development emerge. These lessons have been learned from the more limited U.S. pricing projects, as well as from international projects, and are applicable to "partial" pricing as well as broad-scale congestion pricing.

Congestion Must Be Seen as a Major Problem. When a congestion pricing proposal is presented to the public, the conversation should begin with review of the problem being addressed—traffic congestion and its economic and social costs. Only when a sufficient number of people view congestion as a major problem that congestion pricing will have a chance of public acceptance. The public is not likely to accept congestion pricing if it appears that the primary purpose of the new charges is simply to generate revenue.

Other Project Goals are Important. Congestion relief is the primary rationale for congestion pricing, but other project goals can also garner support. Of particular importance are clear statements about planned use of toll revenues for investments with a high level of public support such as transit improvements that were part of New York City's cordon pricing proposal.

Familiarity Breeds Support. Where the opportunity already exists to use tolled facilities, the likelihood of acceptance of variable tolling is higher than where people are unfamiliar with tolling in general. Further experience with congestion pricing is an important factor in explaining variations in people's views on this approach to dealing with traffic congestion. This has been observed with partial pricing projects in the U.S., where many initial opponents of proposals for priced lanes have been converted to supporters after seeing them in operation. This has been observed as well as with broader pricing approaches abroad. Many initial opponents of broad-scale congestion pricing express the view that pricing will not work because people cannot or will not change their mode or time of travel. What this view ignores is that "most" people do not have to change their travel patterns for congestion pricing to be effective in reducing congestion. If some do on some days, this can be enough to appreciably reduce congestion. Experience has borne this out and has often convinced one-time opponents that congestion pricing can work.

Presenting Congestion Pricing as Offering New Choices is Important. The chances for gaining support for congestion pricing are enhanced when pricing is presented as offering new and better travel choices such as improved alternative transportation modes, along with flextime and telework opportunities. People make travel choices every day by choosing a time to travel, a mode of travel, or whether or not to make the trip. A new way of charging for road use can affect all these choices and present travel opportunities with reduced congestion and perhaps a broader array of travel choices.

Public Involvement is an Essential Part of Project Development. One clear lesson emerging from experience with congestion pricing to date is that, if project implementation is to be successful, affected citizens need to be given full information about the proposed pricing project and its goals, and need to be given the opportunity to see and evaluate the trade-offs involved with different ways of dealing with traffic congestion. Local stakeholders need to be given the opportunity to be involved in project design and development and to provide project planners with continuing advice and feedback on project options.

The VPPP has begun to open the door to public acceptance for pricing. This is a significant accomplishment. However, as noted, the implemented VPPP projects have primarily been HOV to HOT conversions. Clearly, HOT lanes will continue to provide congestion relief and will further public acceptance of pricing as a viable solution for congestion management and reduction. Nevertheless, it appears that there may be a window of opportunity opening to spur implementation of broader, more aggressive pricing strategies such as cordon or expressway system pricing. Many are debating the best course to pursue: the more incremental approach where HOT/Express lanes are seen as necessary precursors to bold congestion pricing versus an approach that encourages bold transformational changes. It may be that these two approaches should be pursued concurrently. Some ideas for consideration along each path are offered below.

Incremental Progress: Congress can choose to continue the VPPP's current defacto focus on an incremental approach whereby HOT lanes provide the path forward to more aggressive pricing strategies. This approach provides a vehicle for demonstrating the value and feasibility of pricing, while providing the option of a reliable trip to travelers willing to pay. In locations where HOT lanes are operational, travelers have valued this choice. However, opportunities for conversions from HOV to HOT are limited because there are not many existing HOV lanes that are underutilized, and others present operational challenges. Creating newly constructed HOT lanes is a relatively slow and costly process. And as a "partial" pricing approach, HOT lanes have a modest impact on national goals such as more efficient use of resources, generation of revenue for transportation investment, and support of economic productivity, environmental sustainability and livable communities.

Some areas are increasing HOV occupancy requirements on overutilized HOV lanes to facilitate conversion from HOV to HOT. Spare capacity to be priced is "created" on existing HOV lanes by causing some HOV-2 vehicles to shift to free lanes or form larger carpools to avoid the new tolls. Data from evaluation of such a strategy being implemented in Miami and in Atlanta should provide more information on the overall effects on vehicle volumes and congestion in adjacent free lanes, and the desirability of this approach. Another option might involve simply pricing HOV-2 vehicles to restore free-flowing conditions on HOV-2 lanes, while keeping service on the lanes free for HOV-3 vehicles, and refraining from opening the HOV lanes to priced single-occupant vehicles. This strategy is used with the QuickRide program in Houston on US 290. Such policy options could be explored further, and may facilitate conversions from HOV to HOT lanes. They would have a modest impact on national goals, since they are partial pricing approaches, but they could demonstrate to the public the value and feasibility of pricing, while providing the option of a reliable trip to travelers willing to pay.

Another approach might be to focus on existing toll roads. Toll roads generally do not need Federal authority to employ congestion pricing. Also, since they are already tolled, the public is less likely to oppose pricing them for the purpose of achieving improved performance. A key hurdle in this approach is the limited ability and willingness of most toll authorities to share toll revenue with transit agencies. Further, many State constitutions or other State laws prohibit the use of highway trust fund revenues (which might include revenue from tolls) for non-road projects. As we discussed in Section VI, a key factor to ensure success of congestion pricing and public acceptance is the concurrent provision of improved transit services, which will need financial support.

Many large metropolitan areas are considering longer-term strategies involving development of networks of HOT or express lanes, and one metropolitan area (the San Francisco Bay Area) has already adopted such an approach for its long-range transportation plan. What this approach can provide is a reliable trip for rush hour travelers willing to pay the price and generation of some surplus revenue (after paying for operating costs) where existing HOV lanes are converted to HOT lanes. These surplus revenues could be used to pay for new transit services, as in the case of San Diego's HOV to HOT conversion on I-15, or in the case of existing HOV lanes that are proposed to be converted to HOT lanes on I-95/395 in Northern Virginia.

However, some studies have concluded that where networks involving new HOT lanes are proposed to be constructed, these networks will not be financially self-supporting, because of the high cost of adding new lanes in urban areas, as discussed earlier, as well as high costs of direct connectors between intersecting HOT lanes at freeway interchanges. Tax support will therefore be needed for these networks. What this approach could provide is a reliable trip for rush hour travelers willing to pay the price, and a more complete express network for carpools and buses. Since some congestion remains on the free lanes, freight mobility and business productivity will continue to degrade, albeit more slowly. There would be a very limited impact on long-term issues such as environmental sustainability and creation of livable communities. Nonetheless, HOT lane networks can show the public how pricing works on a much broader scale, and familiarize them with pricing. This familiarity could perhaps lead to public acceptance of more aggressive forms of pricing with higher levels of impact. Congress may therefore want to consider ways to support this strategy.

Broad-Scale Pilot Approach: To date, the VPPP has not spurred pilot implementation of broad congestion pricing projects on the scale of those operating in London, Stockholm, and Singapore. To make significant progress on congestion pricing strategies more aggressive than partial facility pricing, the Federal Government will need to demonstrate to its citizens the far-reaching benefits from broad-scale congestion pricing. Approaches that could be demonstrated are not simply the type of zone-based pricing approaches that have been implemented internationally and considered in New York, but could also involve pricing of entire travel corridors, all roads in a network of limited-access highways to create a high-performance highway system (DeCorla-Souza 2007) or all roads in a network of major roadways including arterials, such as the concept pilot-tested by the PSRC. If Congress chooses this route, it will need to provide for tolling authority for such a pilot or pilots in reauthorization of Federal legislation. However, a broad-scale implementation project is not likely to move forward without significant Federal funding support, on the scale that moved Mayor Bloomberg to champion the New York City proposal. Federal funding would need to be available for a long enough period to allow for effective public and political outreach to gain the needed local and State legislative approvals. As with the Stockholm project, it may also be helpful to propose pilot project(s) as a "trial" with an opportunity for an up or down referendum vote after the trial period.

Berg, J.T. (2003) "Listening to the Public: Assessing Public Opinion about Value Pricing," Minneapolis, Minnesota, State and Local Policy Program, Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs

DeCorla-Souza, Patrick (2005). FAIR Highway Networks: A New Approach to Eliminate Congestion on Metropolitan Freeways. Public Works Management and Policy, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2005, pp. 196-205. Available at: http://pwm.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/9/3/196

DeCorla-Souza, Patrick (2006). Improving Metropolitan Transportation Efficiency With FAST Miles. Journal of Public Transportation, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2006. Available at: http://www.nctr.usf.edu/jpt/pdf/JPT%209-1%20Decorla-souza.pdf

DeCorla-Souza, Patrick (2007). "High-Performance Highways." Public Roads. May/June 2007. Available at: https://highways.dot.gov/public-roads/mayjun-2007

DeCorla-Souza, Patrick (2009). Congestion Pricing With Lane Reconfigurations to Add Highway Capacity. Public Roads. Federal Highway Administration. Mach/April 2009. Available at: https://highways.dot.gov/public-roads/home

Department for Transport (2004). Feasibility Study of Road Pricing in the U.K. Available at: http://www.dft.gov.uk/pgr/roads/introtoroads/roadcongestion/feasibilitystudy/studyreport/

K.T Analytics and Cambridge Systematics Inc. (2008). Value Pricing Pilot Program: Lessons Learned. Prepared for the Federal Highway Administration. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop08023/vppp_lessonslearned.pdf

K.T Analytics (2008). Lessons Learned From International Experience in Congestion Pricing. Prepared for the Federal Highway Administration. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop08047/Intl_CPLessons.pdf

Higgins, T.J. (1997) "Congestion Pricing: the Public Polling Perspective," Washington, D.C., Transportation Research Board.

National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board (2008). Evaluating Alternative Scenarios for a Network of Variably Priced Highway Lanes in the Metropolitan Washington Region. Available at: http://www.mwcog.org/uploads/committee-documents/aF5fWVlW20080314161420.pdf

Noblis, Inc. (2008) Roadway Network Productivity Assessment: System-Wide Analysis Under Variant Travel Demand. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop09019/fhwahop09019.pdf

Puget Sound Regional Council (2009). Transportation 2040: Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Available at: http://psrc.org/projects/trans2040/deis/index.htm

The Louis Berger Group, Inc. (2009) Examining the Speed-Flow-Delay Paradox in the Washington, DC Region: Potential Impacts of Reduced Traffic on Congestion Delay and Potential for Reductions in Discretionary Travel during Peak Periods. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop09017/fhwahop09017.pdf

Volpe National Transportation Systems Center: Margaret Petrella, Lee Biernbaum, and Jane Lappin (2008). Exploring a New Congestion Pricing Concept: Focus Group Findings from Northern Virginia and Philadelphia. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/tolling_pricing/resources/report/cpcfocusgrp/congestion_focus_grp.pdf

Zmud, Johanna and Carlos Arce "Compilation of Public Opinion Data on Tolls and Road Pricing," NCHRP Synthesis 377. Transportation Research Board, 2008. Available at: http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_syn_377.pdf

| State | Number of projects funded by the VPP Program* |

|---|---|

| CA | 16 |

| CO | 2 |

| FL | 11 |

| GA | 5 |

| IL | 2 |

| MD | 3 |

| MN | 8 |

| NJ | 4 |

| NY | 2 |

| NC | 1 |

| OR | 2 |

| PA | 1 |

| TX | 10 |

| VA | 3 |

| WA | 9 |

*Includes projects granted no funding but only tolling authority, as well as funded projects that may have been terminated or withdrawn, or are currently under development, have been completed and/or are currently operational

| State | Locality | Project |

|---|---|---|

| California | Riverside | Assessment of PierPass, Off-Peak Truck Discounts |

| San Diego | SANDAG Smart Parking-Pricing | |

| San Francisco | Car Sharing Pricing Innovations | |

| Santa Clara | Investigation of Pricing Strategies in Santa Clara | |

| Santa Clara | HOT lane on connector ramp | |

| San Francisco | SF Park Parking Management Program | |

| Florida | Tampa | Dynamically Priced Car Sharing with Zipcar |

| Miami | HOT Lanes on I-95 (Toll Authority only) | |

| Illinois | Chicago | Comprehensive Pricing In Northeast Illinois |

| Minnesota | Twin Cities | Parking Pricing Demo in the Twin Cities |

| Twin Cities | Mileage Based User Fee Regional Outreach | |

| Twin Cities | FAST Miles in the Twin Cities | |

| Twin Cities | Tolling on Dynamically Priced Shoulder Lanes on I-35W | |

| Twin Cities | Tolling on Dynamically Priced Shoulder Lanes on I-94 | |

| Twin Cities | Tolling on Dynamically Priced Reversible Median Lane on Rte 77 | |

| New Jersey | New York metro area | All Electronic Toll Collection |

| New York | New York City | On-Street Parking Pricing |

| New York State | Pilot test of Truck VMT fees | |

| Washington | King County | Pay as you Drive Insurance |

| Seattle | Open Road Tolling on SR-520 | |

| Puget Sound region | Outreach for Puget Sound Tolling Strategies | |

| Seattle | Express lanes system concept study |

| State | Locality/ Year Implemented | Project |

|---|---|---|

| HOT Lanes | ||

| California | San Diego/ 1996 (low tech) 1998 (electronic tolls) |

HOT lanes on I-15: Toll varies dynamically from depending on traffic demand. In 2008 and 2009, the lanes were extended. |

| Colorado | Denver/2006 | HOT lanes on I-25: Tolls vary according to a fixed rate from 50 cents to $3.25 depending upon traffic demand. Buses and 2 person and larger carpools are free. |

| Florida | Miami/2008 | HOT lanes on I-95: Tolls vary dynamically from 25 cents up to $6.20 (i.e., $1.00 per mile) depending on traffic demand. Buses and 3-person carpools are free. Tolls in effect 24 hours a day. |

| Minnesota | Minneapolis/2005 | HOT lanes on I-394: Tolls vary dynamically from 25 cents to $8.00 depending on traffic demand. Buses and two-person and larger carpools are free. |

| Texas | Houston/1998 | HOT lanes on Katy Freeway (I-10): Up to 2008, $2 toll charged to two-person carpools in the peak hour of the peak period; three-person and larger carpools were free. In 2008, facility was expanded. Two-person carpools are now free. Tolls vary from 60 cents to $1.80. |

| Texas | Houston/2000 | HOT lanes on US 290: Toll policy same as for I-10, but applies only to morning peak period. |

| Utah | Salt Lake City/2006 | HOT lanes on I-15: Offers a limited number of flat rate monthly stickers priced at $50.00 to allow single-occupant vehicle access; value priced electronic tolling planned for implementation by 2009. |

| Washington | King County/Seattle 2008 | HOT Lanes on SR 167: Tolls vary dynamically from 50 cents - $9.00 depending upon traffic demand. Buses and two-person and larger carpools are free. Tolls in effect between 5 a.m. and 7 p.m. |

| Pricing on New Lanes | ||

| California | Orange County/1995 | Express Lanes on SR91: Toll varies from $1.20 to $10.00 depending on traffic demand. |

| Pricing on Toll Roads | ||

| California | Orange County/2002 | Peak pricing on the San Joaquin Hills mainline: Toll surcharge of 75 cents during the peak period at the mainline toll plaza; tolls are $3.50 in off-peak and to $4.25 in peak. |

| Florida | Lee County/1998 | Variable pricing of two bridges: 50 percent toll discount (amounting to 25 cents) offered in shoulders of the peak periods (westbound direction only). |

| New Jersey | New York metropolitan area/2001 | Variable tolls on interstate crossings: Off-peak tolls discounted by 25 percent relative to peak period tolls, i.e., $6 vs. $8. |

| New Jersey | Statewide/2000 | Variable Tolls on New Jersey Turnpike: Peak period toll exceeds off-peak toll by 24.8 percent for the entire 148 mile (238 km) length, off-peak toll is $4.85 vs. peak toll of $6.45. |

| Projects Not Involving Tolls | ||

| California | San Francisco/2001 | Car sharing: Charges are $5 per hour (12 p.m. - 8 a.m.) plus 40 cents per mile, and $1 per hour (other times) plus 40 cents per mile. |

| Washington | Seattle/2002 | Parking cash-out: Monthly average parking cost in downtown Seattle is about $175. This is the amount those cashing out might expect to receive. |

| Washington | Seattle/2000 | Cash out of cars: Weekly average cost for owning a car was estimated at $326.00. This is the amount those "cashing out" their cars might expect to save. |

(Including projects that have not received grant awards or tolling authority from the VPPP)

| State | Locality | Project |

|---|---|---|

| California | Alameda Co. | I-880/I-680 |

| Alameda Co. | Highway pricing with dynamic ridesharing | |

| Alameda Co. | I-680 SMART Carpool Lanes | |

| Los Angeles Co. | HOT lanes on I-10 and I-110 (Toll authority planned from Section 166) | |

| Orange County | SR 91 evaluation | |

| Orange County | Implementation of peak pricing on the San Joaquin Hills Toll Road | |

| Orange County | Implementation of Dynamic Pricing on SR 91 | |

| Riverside | Assessment of PierPass, Off-Peak Truck Discounts | |

| Santa Clara | Investigation of Pricing Strategies in Santa Clara | |

| Santa Clara | Implementation of pricing on HOV connector ramp | |

| Santa Cruz | HOT lanes on median of Route 1 | |

| San Diego | Extension of I-15 HOT lanes | |

| San Diego | Violation Enforcement System on I-15 HOT Lanes | |

| San Diego | Smart Parking-Pricing | |

| San Francisco | Car Sharing Pricing Innovations | |

| San Francisco | Area Road Charging and Parking Pricing | |

| San Francisco | Comprehensive Smart Parking | |

| Colorado | Denver | I-25 HOT Lanes (Toll authority provided from Section 166) |

| Denver | C-470 New Priced Lanes | |

| Florida | Broward County | Variable Tolls on the Sawgrass Expressway |

| Broward County | I-595 Express Lanes (Toll authority planned from VPPP) | |

| Fort Myers Beach | Cordon Pricing Study | |

| Statewide | Sharing of Technology on Pricing | |

| Lee County | Pricing on Bridges | |

| Lee County | Priced Queue Jumps | |

| Lee County | Variable Tolls for Heavy Vehicles | |

| Lee County | Pricing on Sanibel Bridge and Causeway | |

| Miami-Dade | Pricing Options on the Florida Turnpike | |

| Miami-Dade | HOT Lanes on I-95 (Research and Outreach) | |

| Miami | HOT Lanes on I-95 (provided toll authority from VPPP) | |

| Tampa | Dynamically Priced Car Sharing with Zipcar | |

| Georgia | Atlanta | Simulation of Pricing on Atlanta's Interstate System |

| Atlanta | Express Toll Lanes on I-75 | |

| Atlanta | I-75 South HOT/Truck Toll Only Study | |

| Atlanta | Variable Pricing Institutional Study for GA-400 | |

| Atlanta | HOT lanes on I-85 (Toll authority planned from Section 166) | |

| Savannah | Northwest Truck Tollway | |

| Illinois | Chicago | Variable Tolls on the Northwest Tollway |

| Chicago | Comprehensive Pricing In Northeast Illinois | |

| Maryland | Statewide | Feasibility of Pricing at Ten Locations |

| Baltimore | Express Toll Lanes on Section 100 of I-95/JFK Expressway (Toll authority provided from VPPP) | |

| Baltimore | Express Toll Lanes on Section 200 of I-95/JFK Expressway (Toll authority provided from VPPP) | |

| Minnesota | Statewide | Variabilization of Fixed Auto Costs |

| Twin Cities | Project Development Outreach | |

| Twin Cities | Parking Pricing Demo in the Twin Cities | |

| Twin Cities | Mileage Based User Fee Regional Outreach | |

| Twin Cities | FAST Miles in the Twin Cities | |

| Twin Cities | Tolling on Dynamically Priced Shoulder Lanes on I-35W | |

| Twin Cities | Tolling on Dynamically Priced Shoulder Lanes on I-94 | |

| Twin Cities | Tolling on Dynamically Priced Reversible Median Lane on Rte 77 | |

| New Jersey | New Jersey | Variable Tolls on the New Jersey Turnpike |

| NY Metro Area | Variable Tolls on Water Crossings | |

| NY Metro Area | Express Bus/HOT Lane for the Lincoln Tunnel | |

| NY Metro Area | All Electronic Toll Collection | |

| New York | New York City | Parking Pricing in Manhattan |

| New York State | Pilot test of Truck VMT fees | |

| North Carolina | Raleigh/Piedmont | HOT Lanes on I-40 |

| Oregon | Statewide | Mileage Based User Fee Evaluation |

| Portland | Express Toll Lanes on Highway 217 | |

| Pennsylvania | Philadelphia | Variable Tolls on the PA Turnpike |

| Texas | Austin | HOT Lane Enforcement and Operations on Loop 1 |

| Austin | Truck Traffic Diversion Using Variable Tolls | |

| Dallas | Regional Value Pricing Feasibility Study | |

| Dallas | Managed lanes on I-635 (Toll authority provided from Express Lanes Demo Program) | |

| Dallas | Express Toll Lanes on I-30/Tom Landry Freeway | |

| Ft. Worth | North Tarrant Express Lanes (Toll authority from Express Lanes Demo Program) | |

| Houston | HOT Lanes on I-10 and US 290 | |

| Houston | HOT Lanes on Katy Freeway (expansion) | |

| Houston | Houston HOT Network | |

| Utah | Salt Lake City | HOT lanes on I-15 (Toll authority provided from Section 166) |

| Virginia | Hampton Roads | Variable Pricing in the Hampton Roads Region |

| DC Metro Area | HOT lanes on the Capital Beltway (Toll authority planned from Section 166) | |

| DC Metro Area | Regional Network of Value Priced Lanes | |

| Washington | King County | Parking Cash Out |

| King County | Cash Out of Cars | |

| King County | Pay as you Drive Insurance | |

| Seattle area | GPS Based Pricing | |

| Seattle area | Outreach for Puget Sound Tolling Strategies | |

| Seattle area | HOT Lanes on SR 167 | |

| Seattle area | Open Road Tolling on SR-520 | |

| Seattle area | Express lanes system concept study |

Five projects have been implemented since April 2006. More details on projects implemented prior to April 2006 have been provided in previous reports to Congress.

The I-25 Bus/HOV lanes, also known as Downtown Express lanes, are a two-lane barrier-separated reversible facility in the median of I-25 between downtown Denver and 70th Avenue, a distance of 6.6 miles. The facility opened as a HOT facility on June 2, 2006. In March of 2009, 88,114 vehicles paid a toll to travel in the I-25 Express Lanes. A total of $164,007 in toll revenue was collected. More than 1,800 toll-paying vehicles are using the lanes in the morning peak period and more than 1,400 toll-paying vehicles are using the lanes in the afternoon peak period. Carpools, buses and motorcycles continue to use the lanes toll-free as long as they are in the lane marked "HOV" when they pass through the toll collection point near 58th Avenue. That is the only time there is a designated lane for HOVs and for toll paying vehicles. Toll rates for the I-25 Express Lanes vary by time of day to ensure the lanes remain free-flowing. HOT lane traffic consistently flows freely during all hours of the day. Toll collection is electronic only. No cash is accepted. The use of the previously underutilized HOV lanes is now being maximized, giving motorists another option to escape traffic congestion.

On May 3, 2008, HOV lanes on State Route (SR) 167 in King County/Seattle were converted to HOT lanes. The project extends from Southwest 15th Street in Auburn to I-405 in Renton. This 4-year pilot project will evaluate the ability of the HOT lane concept to manage congestion and generate revenue. Preliminary results indicate that the number of daily tolled trips has continued to increase, although the average toll paid by customers has fallen slightly below $1.00 per trip. The revenue generated by the tolls has climbed to just under $30,000 per month in March 2009. HOT lane traffic consistently flows freely during all hours of the day. During the 4-year pilot, the performance, socio-economic impacts, and public acceptance of the facility will be assessed on an annual basis.

The Miami-Ft. Lauderdale region is creating a 21-mile managed-lane facility on I-95, between I-395 and I-595, with a longer term goal of providing a network of managed lanes throughout the congested region. The express facility is being created by converting a single HOV lane in each direction into two HOT lanes in each direction by narrowing the travel lanes from 12 ft. to 11 ft. and narrowing the shoulders. The first segment, the southern half of the northbound I-95 HOT lanes, opened in December 2008. This is the second project in the Nation (after the Houston QuickRide project) to increase the occupancy requirement on HOV lanes, in this case from HOV 2+ to HOV 3+. The new occupancy requirement will ensure that the lanes remain free-flowing as HOV demand increases in the future, and will create some excess capacity for priced vehicles. The Express lanes generated monthly toll revenue of about $386,300 in March 2009 bringing the total revenue to date to approximately $1.01 million. Tolls ranged from $0.25 to the highest toll for the month of $3.00. The average off-peak toll was only $0.50. Approximately 88 percent of the customers were charged $1.75 or less. The facility operates at 15 mph above the adjacent toll-free lanes during the p.m. peak period (4 p.m. to 7 p.m.) and operates above 45 mph 100 percent of the time.

The I-15 HOT lanes are being extended to create a 20-mile "Managed Lanes" facility in the median of Interstate 15 (I-15) between State Route 163 and State Route 78. When completed, there will be a 4-lane facility in the median with a moveable barrier, multiple access points from the regular highway lanes, and direct access ramps for buses from five transit centers. A high frequency bus rapid transit system is under development and will replace the existing express buses that serve the corridor. The first 4.5 miles of new HOT lanes opened to traffic on September 22, 2008. Another 3.5 miles were opened to traffic on March 16, 2009. Latter stages will include four additional miles of new Managed Lanes by 2011, and the widening of the original 8-mile reversible section by 2012. When complete, the new State-of-the-art system will collect tolls from over 30 locations covering 84 "tolled lanes."

Katy Freeway (I-10), in the western portion of Houston, is a heavily congested urban interstate facility. The existing freeway is 23 miles long and consists of six general-purpose main lanes (three in each direction), with two-lane continuous one-way frontage roads in each direction for most of its length. Additionally, the freeway has a one-lane reversible HOV lane between I-610 and State Highway 6, and one HOV lane in each direction between State Highway 6 and the Grand Parkway (State Highway 99). The freeway is being expanded to eight general-purpose lanes, four in each direction, with continuous three-lane frontage roads in each direction. In addition, in the center of the facility from I-610 west to State Highway 6, four HOT lanes were constructed, two in each direction. From State Highway 6 to the Grand Parkway, two HOT lanes were constructed, one in each direction. The first segments of the HOT lanes opened in April 2009.

In mid-August 2007, the DOT announced the designation of five metropolitan areas (Miami, Minneapolis-St. Paul, New York City, San Francisco, and Seattle) as "Urban Partners," based on the results of a comprehensive review and competitive selection process. Each Urban Partner agreed to implement a comprehensive policy response to urban congestion that includes what DOT referred to as the "4 Ts": (1) a tolling (congestion pricing) demonstration, (b) enhanced transit services, (c) increased emphasis on teleworking and flex scheduling, and (d) the deployment of advanced technology. The approaches taken vary between Partner jurisdictions (e.g., HOV-to-HOT lane conversion in Miami vs. full facility pricing in Seattle), but in each case the projects represent innovative solutions.

UPA Project Summaries:

The Congestion Reduction Demonstration (CRD) Program:

Chicago, Los Angeles, and Atlanta were selected to partner with DOT on this program

On-going Research:

Completed Research:

On-going Research:

On-going Research:

Large road pricing projects have been implemented in the U.K., France, Norway, Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, Singapore, and Australia over the past three decades. Additionally, congestion pricing has been analyzed and evaluated through numerous studies in nearly all European Union member countries, in Southeast Asia, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

To further understanding of international pricing, the FHWA report "Lessons Learned from International Experience in Congestion Pricing" (K.T. Analytics, Inc. 2008) provides a summary of selected operational area-wide congestion pricing projects outside of the U.S. The report draws lessons from a sample of projects with the richest and most relevant experience, focusing on three comprehensive area wide projects: Singapore, London, and Stockholm.

Congestion pricing has been a major component of traffic management and emissions reduction in Singapore. The Area Licensing Scheme was established in 1975 when a charge of S$3.0 (US$1.30) was introduced for vehicles entering the 2.0 square-mile central business area ("Restricted Zone" - RZ) between 7:30 and 9:30 in the morning. Buses, motorcycles, police vehicles and four-person carpools were excluded from charges. Introduction of congestion pricing was accompanied by provision of new Park-and-Ride lots with shuttle service into the RZ and expanded bus service (33 percent increase).

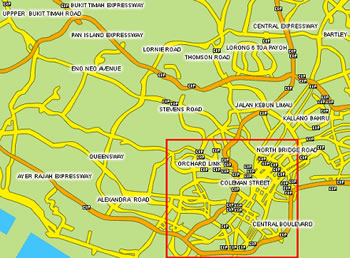

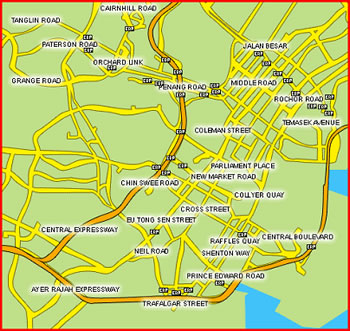

Since introduction, the Singapore congestion pricing program has gone through several modifications and expansion. Electronic Road Pricing (ERP), with charges varying by time of day, location and type of vehicle was introduced in 1998 for vehicles entering the central priced zone and at three points along three motorways. Subsequently, pricing has been extended to many more points on all motorways. The ERP program has been fully automated and charges are now collected electronically at more than 50 charge points spread across the city, as shown in Figure 1.

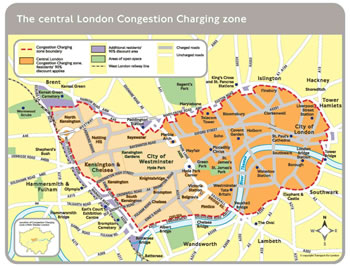

The Congestion Charging program commenced in London in February 2003. It covered the 8.0 square mile, heavily congested central business district shown in Figure 2. The eastern zone shown with darker shading was designed as the "charging zone." The charging zone represented less than 1.5 percent of the total area of Greater London. Subsequently, the charging zone was extended to the west to cover an additional 8.0 square miles (shown in lighter shading in Figure 2). The overall program package included 40 percent increases in capacity of buses and trains over an 8-year period, starting immediately with expansion of bus service.

The program entails a flat weekday fee. Initially set at £5, the fee was raised to �8 in 2005. The fee is charged to vehicles crossing into, leaving, or traveling within the charging zone. The charging is effective between 7:00 a.m. and 6:30 p.m. (modified in 2007 to 7:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m.).

Figure 1a: Singapore Electronic Road Pricing (2005)

[CBD Priced Zone (Inset) and Expressways (Red)]

Figure 1b: Singapore CBD Priced Zone (2005)

Source: K.T. Analytics, Inc (2008)

Figure 2: THE CENTRAL LONDON CONGESTION CHARGING ZONE

2003 Original Charging Zone - Eastern Dark Shaded Area

2005 Expansion Zone Added - Western Light Shaded Area

(Excludes North-South Edgware/Park/Vauxhall Roads)

(Inset: Charge Zone Within Greater London Area)

Source: K.T. Analytics, Inc (2008)

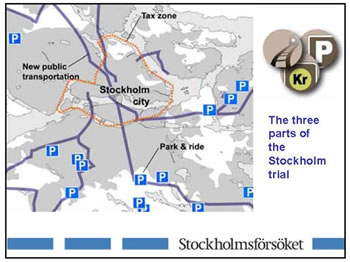

The central city area of approximately 20 square miles is designated as the priced zone. It covers the central city and constitutes a small part of the urbanized county area. The three elements of the program are shown in Figure 3 - Charging Cordon, Expanded Transit Routes and New Park-and-Ride Lots.

The charges are in effect weekdays from 6:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. and the price is set at 10, 15 and 20 SEK (US$1.33, 2.00 and 2.67 at 2006 rates) for off-peak, shoulder and peak period, respectively. The charges are collected when entering or exiting the zone at 18 barrier free "control points" encircling the city center. The daily maximum charge for multiple crossings is set at 60 SEK (US$8.00).

Figure 3: Stockholm Priced Zone Shown Within The Inner County

(Expanded Transit Routes and PAR Facilities Also Shown)

Source: K.T. Analytics, Inc (2008)

Mobility: Without exception, broad-scale pricing strategies implemented abroad have met their principal objective of reducing congestion and sustaining relief. Broad-scale pricing in Singapore, London, and Stockholm has resulted in 10 to 30 percent or greater reduction in traffic in the priced zone and has sustained the reductions over time. The speeds increased significantly within the zone as well as outside along approach roads. Ten to 30 percent increase in speed has been realized. Buses in Singapore and London have particularly benefited from speed increases. In the three broad-scale pricing programs, up to 50 percent of those foregoing car travel to the priced zone shifted to public transportation. In London and Stockholm, the greatest shift was to public transportation while in Singapore it was to 4+ carpools and to car travel during the shoulder time just before the start of pricing. The traffic reductions in priced zones have been sustained over 30 years in Singapore and 5 years in London.

Revenues/Costs: The significant revenues generated by pricing have been seen as an important source of benefits in all three projects. Project revenues in London and Stockholm (as well as in toll cordon projects in Norwegian cities) have been used to cover operating and enforcement costs first and remaining revenues have funded improvements to bus and rail services. In London and Stockholm, the desire and ability to use pricing program revenues for public transportation was a major objective and "selling" point. In Singapore, while the revenues are not directly dedicated for public transportation, the availability of these funds probably has allowed the government to more easily to pursue ambitious public transportation programs. Also, broad-scale pricing projects are generating revenues far in excess of costs. In Singapore's Area Licensing Program, revenues were nearly 10 times the operating costs. The revenues under the central area cordon pricing program are nearly 14 times the operating costs. If capital costs are included, the revenues are still 2.5 times the costs. For the London charging program, the revenues have been a little over twice the operating costs. Inclusion of capital costs brings this ratio down only marginally.

Economy and Business: Broad-scale congestion pricing applications appear to have realized societal economic benefits in excess of costs. Singapore's 1975 program is estimated to have achieved a rate of return on investment of at least 15 percent, even without inclusion of realized savings other than the value of time savings. The London scheme is estimated to have generated a B/C ratio of 1.4: 1. Regarding business impacts, in Singapore, surveys suggested that the pricing program did not change business conditions or location patterns. Overall, the business community responded positively to the program. Analysis indicates pricing in London has neutral regional economic impacts, though annual surveys suggest businesses in the priced zone have outperformed those outside. A majority of businesses continue to support the charging scheme, provided investment in public transportation is continued. In Stockholm surveys, albeit over a very short time span of trial, no identifiable impacts on retail business or household purchasing power were identified. The long-term study of overseas congestion pricing conduced by CURACAO, (i.e., Coordination of Urban Road-user Charging Organisational Issues (CURACAO 2007)) finds "generally low level of measured impact" on regional economies. While the result may be partly attributable to the unique economic vitality and strength of the cities in which pricing occurs, there is no evidence of economic damage.