STEP 1 – ASSESSMENT OF NEEDS

This section describes key activities or considerations that should be addressed in Step 1 of the implementation process, in which the work zone needs are established and preliminary information is gathered. The sub-steps that will be explored in Step 1 are depicted in Figure 5.

1.1 What are the user needs?

Users are those who will use and directly benefit from the outputs of the work zone ITS system. Most often, user needs are in reference to travelers, but user needs may also be identified for the agency or contractor. Each work zone presents different challenges and unique circumstances that affect user needs. Table 2 provides examples of some of the issues that may be encountered in a work zone and need to be addressed.

The first sub-step in Step 1 is to determine what issues/needs exist for the work zone. This should be performed in the context of an overall assessment of the expected impacts of the work zone, and in coordination with the transportation management plan (TMP) development process for the work zone.7 This larger perspective is important because there may be more than one TMP strategy that can address the need, and work zone ITS may not be the best alternative to mitigate these issues Determining the user needs first will help an agency better decide whether work zone ITS will adequately address the problem at hand and if it is the most suitable solution. Work zone ITS should be intentionally applied as a carefully designed solution to a well-defined problem.

| This project provides an example of the importance and value of considering user needs early in the work zone planning process. The McClugage Bridge consists of two independent spans, each serving one direction of US 24/US 150 travel through Peoria and across the Illinois River. During the rehabilitation effort, the eastbound span of the bridge was closed completely, and traffic in both directions of travel was placed on the westbound span. The Illinois DOT and the contractor elected to use both a movable barrier system and work zone ITS to try to address mobility problems expected from the bridge closure. However, officials found that the movable barrier provided sufficient peak period and peak direction capacity through the work zone that the congestion that was feared never materialized. As a result, the work zone ITS never had to be activated during the project.

Not all user needs will automatically imply that work zone ITS is required. Analysis in subsequent steps of concept development may indicate that some other approach to mitigating the problem to address the user need is more appropriate, or may verify that the work zone ITS solution is needed. In this example, greater consideration of the effect of the moveable barrier may have indicated that there was not a significant user need to warn approaching traffic about travel conditions such as stopped traffic. Satterfield, C. Moveable Barrier Solves Work Zone Dilemma. In Public Roads, Vol. 65, No. 1, July/August 2001, pp. 26-29. Accessible at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/01julaug/workzone.cfm. |

Examples of mobility issues or problems:

|

Examples of safety issues or problems:

|

Examples of productivity issues or problems:

|

When identifying and describing the user needs for a particular project, it is important to be as specific as possible. For example, the Illinois DOT identified unexpected queue formation at work zones in semi-rural areas as a concern. They specified that that these concerns existed whenever a temporary lane closure or long-term road closure was required, and whenever a vehicle stall might occur (because of a lack of emergency shoulders to move the vehicle out of travel lanes). Trying to reduce the effects of unexpected queues, coupled with the unpredictability of the events causing those queues, was the specific user need to be addressed. Similarly, the Texas DOT also had a user need to reduce the effects of unexpected queues during construction projects along I-35. However, in defining their needs they also desired to minimize the amount of equipment deployed within each of the several projects that were ongoing simultaneously along the 90+ mile corridor. They also wanted to be able to accurately detect and measure the length of queue that developed at each temporary lane closure installed so that forecasts of delay impacts from the closure could be disseminated to motorists farther upstream. Thus, their specific user needs were somewhat different from those of ILDOT, even though both were concerned about the same general issue.

Another consideration are regulatory requirements or agency policies associated with monitoring and assessing the impacts of a work zone. For example, an agencys policy may limit work zone delays to 20 minutes. Work zone ITS can be used to monitor if a work zone is meeting the agency’s target. 23 CFR Subpart C (sometimes referred to as the 1201 rule from the SAFETEA-LU Highway Authorization Act of the 109th U.S. Congress)8 establishes minimum requirements for agencies for real-time information, including work zone lane closure information for long-term construction projects. The Work Zone Safety and Mobility Rule (23 CFR 630 Subpart J) requires agencies to use work zone safety and operational data to improve projects and agency policies, processes, and procedures regarding work zone safety and mobility management. Work zone ITS is one of the possible ways to gather data for use in assessing work zone performance.

1.2 What are the system goals and objectives?

An agency must clearly articulate its goals at the outset of the project to best ensure deployment of a system that will satisfy those objectives. Although general goals or objectives for the system may be stated as agency policy, it is the responsibility of staff engineers and planners to translate general goals into specific, measurable, and, most importantly, attainable objectives for the project and the work zone ITS (e.g., no more than 20-minute delays or 2-mile queues). The goals and objectives should address user needs identified in Step 1.1 and through impacts assessment, and also support TMP development. System goals and objectives should also follow SMART criteria, meaning that they are Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-bound. The key factor in this step is to set realistic objectives for the system and avoid the creation of unrealistic expectations that result in diminished credibility in the system’s outputs. In other words, if a work zone ITS would be deployed, what would it do to address user needs?

Those engaged in the goal-setting process should periodically check to ensure that goals or objectives have corresponding means of measurement. In other words, how will success of a system be measured during and after it is deployed? It will be important to match data availability and/or processing capabilities of the system with the desired goals and objectives. For example, if a queue length threshold is established for the project, the system should be capable of providing reasonable queue length estimates. Conversely, if delay is the desired metric, a system that directly measures travel time and delays might be more appropriate.

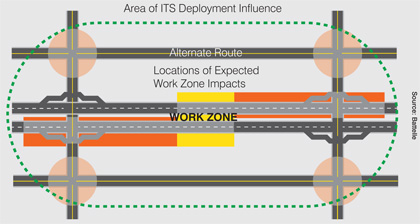

In general, the system should be adequately robust to consider the full impact of the work zone. As shown in Figure 6, for example, the area of ITS influence due to a work zone may include adjacent routes. It is likely that at least some drivers will divert, regardless of whether messages encourage taking an alternate route. This additional traffic may cause congestion on those adjacent routes and should be considered when planning for the ITS. If diversion is expected, ITS devices may be required on alternate routes as well as the mainline. These alternate routes will need to be monitored and managed in order for benefits to be achieved. While the ITS zone on the mainline may extend upstream from the work zone beyond the length of the expected queue (e.g., a queue warning system), and perhaps upstream from a diversion point (e.g., real-time travel information system with comparative travel times or suggesting alternate routes), ITS could also be considered on alternate routes that could be impacted. The FHWA report “Advancing Metropolitan Planning for Operations: The Building Blocks of a Model Transportation Plan Incorporating Operations – A Desk Reference” may serve as a useful guide for this step9.

| If goals and objectives become more manageable to achieve through a different technique, that technique should be selected instead of ITS. Other strategies may be more economical and effective in meeting goals and objectives. |

| Although some ITS applications may be promoted as a catch-all solution to safety and capacity problems, field testing has not always shown conclusive benefits. Work zone ITS should be well designed and smartly applied to scenarios in which benefits are most likely to be achieved. |

| This is particularly important for deployments that are intended to convey delay or queue length information to users. In some deployments, work zone impacts periodically extended beyond the limits of the ITS devices. When this happened, the system was unable to provide accurate information. More importantly, the motorists sat through several minutes of delay before encountering a message that there were delays and reduced speeds in the work zone. This severely limited the credibility, usefulness, and benefits of the system. |

1.3 Who are the stakeholders?

Stakeholders should be engaged early in the project development process to ensure that a full range of possibilities can be considered. Stakeholders include any person or organization that may be affected by construction, and all agencies that are directly involved with motorist assistance, law enforcement, and providing traveler information. Stakeholders are a broader group than users, and include those who are not intended to be primary users of an ITS deployment. Potential stakeholders include:

- State DOT (including those with ITS expertise)

- City transportation agencies

- Metropolitan Planning Organizations

- County transportation agencies

- FHWA Division Office

- Service patrol/contractors

- Construction contractors

- State and local police departments

- Fire departments

- Emergency medical services

- Local businesses

- Shopping centers and other major traffic generators

- Major commercial trucking companies

- Motorists

- Media

- Residents

- Public officials

- Other incident management agencies.

Stakeholders should include policy makers, as well as staff from agencies involved in the deployment, operation, and maintenance of both the work zone and the ITS application. Although not all of these groups may have a direct interest in all of the project’s objectives, they may be able to offer valuable insight that expands the original vision to achieve greater benefits.

If the project is within an area that has already developed a regional ITS architecture, many of the stakeholders would have already been identified. This would be a good place to start to establish a core team to further define the system concept. This group can also help identify other potential work zone information sharing opportunities between jurisdictions and agencies.

Stakeholders must be involved early on for a successful ITS implementation. Input from these groups can result in better deployment plans. It is unlikely, especially for smaller projects, that stakeholders will convene for a meeting solely about ITS; instead discussion regarding ITS will likely be part of a larger agenda, such as on the TMP or the project alternatives and schedule. It is important to ensure that ITS is included on this larger agenda to help stakeholders understand the possible deployment and gain their input and support. Smaller working groups should be developed and convened regularly to keep all stakeholders informed about the progress of an ITS deployment. The goals of such a working group should include keeping stakeholders informed, creating opportunities for input and participation, providing feedback, creating an informed consensus, and identifying the need for system adjustments during deployment. Working group discussions might be combined with related meetings such as those on maintenance of traffic.

Stakeholders need to have input in developing the goals and objectives of the implementation and should review strategies and plans to make sure their needs are being met to the fullest extent possible. Ideally, this input will be gathered as part of the project impacts assessment and TMP development process to support an efficient and coordinated process for work zone management. Stakeholders should review critical steps in system development and should be influential when decisions are being made.

| Coordination with other agencies is a primary issue that should be considered both in developing and implementing an ITS work zone. This will be important for determining how the system can work within each agency’s existing procedures. |

| Utah DOT traffic operations personnel were incorporated early in the project planning process and strived to be proactive in addressing the various mobility concerns that could develop. During the planning process, it became apparent that it would be extremely beneficial to upgrade the arterial signal systems in Provo and Orem to become compatible with the Utah DOT centralized signal system. Utah DOT approached the cities of Provo and Orem and established cooperative agreements to convert their systems to the statewide signal control system in order to better manage travel on the arterial streets adjacent to the freeway. |

1.4 Who should be on the project team?

The next step is to assemble the project team. The project team is the actual working group whose members are drawn from the stakeholder organizations identified in the previous step. It is recommended that the number of people on this team be small because this team will be conceptualizing and planning the project. While it is important to involve a wide range of stakeholders from the very beginning of the project, it is also important to keep working groups small so that these groups can actually get things done. Thus, not all stakeholders will have a representative on the project team. Instead, the project team will be responsible for interfacing with stakeholders that are not on the project team to keep them informed and receive their input. In addition, it is also important not to expect that all stakeholders will be fully “sold” on the project at first. Instead, the lead agency must have patience with “non-believers,” allowing them time to develop trust in the system, as well as trust in other groups involved in the project.

1.5 What, if any, existing ITS resources are available?

Taking an inventory of existing ITS resources in the corridor or region that can be applied to help manage the work zone can help to control system acquisition and deployment costs. For example, there may be a permanent traffic detector within or adjacent to the work zone that can provide archived or real-time data to help predict and/or monitor traffic conditions leading up to and throughout the work zone. There may be permanent CMS upstream of the work zone that can display warnings of stopped or slow traffic ahead or encourage diversion to alternate routes, as presented in Figure 7. Closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras in the area might also be particularly useful for helping to monitor traffic and check for incidents. Any road weather information systems (RWIS)/environmental sensor stations (ESS) in the area can help determine current weather and road conditions that will affect traffic flow. Additionally, the availability of a local traffic management center (TMC) can be very beneficial, as staff could operate ITS for the work zone. An existing traveler information website for the agency or geographic area can be used to provide updates on work zone conditions to the public.

The maintaining agency for these resources can explain the availability of ITS resources for use. For example, CMS may be needed for emergency messages, or it may not be preferred that a message is displayed for all hours due to concerns of burning out the lighting mechanisms and long term maintenance costs. Discussions about stakeholders concerns may result in some creative solutions, such as agreement to place messages on during peak hours of travel.

If existing ITS resources are available and are planned to be used for work zone management purposes, care must be taken to ensure that the resources themselves will remain operational over the duration of the project and access to the systems and data is readily available. The need to temporarily disconnect power or communication lines in the work zone may render permanent ITS devices near the work zone inoperable or inaccessible, or they may even be removed if they are directly in the work area. Construction equipment or vehicles have the potential to block sensors or cameras unexpectedly and repeatedly. To avoid such issues, some agencies include requirements in the bid documents that permanent ITS devices be maintained in an operational state throughout the duration of the project. Agencies may also include disincentive clauses in a contract that are applied if the ITS equipment does not work during peak hours. Functionality of ITS equipment is particularly important in congested areas where the television, radio, and/or social media traffic updates rely on information from the ITS equipment.

In some cases, it may be desirable to mesh or replace available ITS resources with additional temporary devices obtained specifically for a particular work zone. An example of this might be the purchase and installation of portable traffic sensors, cameras, and CMS within and near a work zone on a facility that is not currently covered in a regional ITS, and having the operators within the TMC monitor and manage those temporary devices in addition to the permanent ITS components they normally operate. In such instances, it is important to bring the key decision-making personnel from the center in early in the planning process to help identify needs and issues. The center may need to increase staff to handle the increased workload, for example, and need financial support through the project budget to do so. There will likely be specifications as to how temporary devices must be configured and operated (i.e., National Transportation Communications for ITS Protocol (NTCIP)-compliant cameras) in order to integrate data feeds into the operator consoles.

|

| Key Takeaways |

|

7More information on work zone impacts assessment and TMP development is available at https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/wz/resources/final_rule/guidance.htm.

8The text of Section 511.309 can be found at: http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?c=ecfr&sid=66686edfa10d4ace67b3e67bbc442ef7&rgn=div5&view=text&node=23:1.0.1.6.16&idno=23.

9Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop10027/