Printable Version [PDF 2MB]

To view PDF files, you need the Adobe Acrobat Reader.

Contact Information: Operations Feedback at OperationsFeedback@dot.gov

Publication Number: FHWA-HOP-07-115

Real-time Traveler Information Services Business Models: State of the Practice Review

Prepared for:

Office of Operations

Federal Highway Administration

U.S. Department of Transportation

Washington, DC 20590

Prepared by:

Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc.

in association with

Cambridge Systematics

FHWA-HOP-07-115

May 2007

QUALITY ASSURANCE STATEMENT

The U.S. Department of Transportation (“the Department”) provides high-quality information to serve Government, industry and the public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. The Department periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvements.

Technical Report Documentation Page

|

1. Report No. FHWA-HOP-07-115 |

2. Government Accession No. |

3. Recipient's Catalog No. |

||||

|

4. Title and Subtitle Real-Time Traveler Information Services Business Models: State of the Practice Review |

5. Report Date May 2007 |

|||||

|

6. Performing Organization Code |

||||||

|

7. Author(s) Lisa Burgess, Alan Toppen, Pierre Pretorius (Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc.) |

8. Performing Organization Report No. |

|||||

|

9. Performing Organization Name and Address Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. 7878 N. 16th Street, Suite 300 Phoenix, Arizona 85020 (performed as a subconsultant to Cambridge Systematics) |

10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) |

|||||

|

11. Contract or Grant No. DTFH61-06-D-00004 |

||||||

|

12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Office of Operations Federal Highway Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC 20590 |

13. Type of Report and Period Covered |

|||||

|

14. Sponsoring Agency Code HOTM |

||||||

|

15. Supplementary Notes FHWA COTM: Robert Rupert |

||||||

|

16. Abstract

This State of the Practice Review documents a range of business models for real-time traveler information services, and provides ‘real world’ examples of how States and regions are developing partnerships and business plans within the business model frameworks. Although there are numerous variations on these models, there is no question that there have been shifts in the fundamentals of these traditional business models, as well as new business model structures that have emerged. Included with this review is a summary of current prevalent business models, which include public-sector funded, franchise operations, private sector funded and business-to-business models. It addresses issues such as roles and responsibilities within the models, pros and cons of the various approaches, and provides case study examples of traveler information programs throughout the country.

This document also discusses the trends and impacts that have influenced current traveler information business model approaches, including the impact of 511 on the role of the public sector, trends in data collection and the new role of the private sector as data collector, and some of the resulting data ownership issues. With the prevalence of Web-based, business-to-business and supply-chain information bundling, there are increasing opportunities for private sector to be able to generate revenue either through subscription services or advertising. |

||||||

|

17. Key Word Traveler Information, 511, Business Models, Information Dissemination, Data Collection, Public-Private Partnerships, Business Planning |

18. Distribution Statement No restrictions |

|||||

|

19. Security Classif. (of this report) Unclassified |

20. Security Classif. (of this page) Unclassified |

21. No. of Pages |

22. Price |

|||

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8-72) Reproduction of completed page authorized

Table of Contents

Section 1. Introduction and Project Overview

1.1 Context for the 2007 State of the Practice Review

1.2 Summary of Contributing Factors to Changes in Traveler Information Business Model Approaches

Section 2. Background and Historical Context

2.1 Early Traveler Information System Business Model Approaches

2.2 Lessons and Experiences from European Models

2.3 National Guidance Promotes Quality, Consistency in Traveler Information Services

Section 3. Predominant Traveler Information Business Models and Issues

3.1.1 Public Centered Operations

3.3 Private-sector operated and funded models

3.3.1 Private sector operations without funding from the public sector

3.3.2 Free services supported by advertising

3.3.4 Free basic information with premium services available for a fee

3.4 Value-added reseller models

3.5 Business-to-business models

Section 4. Business Model Trends and Impacts

4.1 Expanded roles for the public sector

4.1.1 Growth and impacts of 511

4.1.2 More than a Weekday Commute Tool

4.1.3 The public sector as data aggregator

4.1.4 Enhanced and Personalized Information Available from the Public Sector

4.2.1 Trends in Sensor Data Collection

4.2.2 Trends in Probe Vehicle Data Collection

4.2.3 Transit Information Services

4.3 Strategies and Challenges for Expanding the Public Sector Traveler Information Programs

4.4 Traveler Information Services Policy Issues for the Public Sector

4.4.1 Responses to Emerging Private Sector Business Models

4.4.3 Traveler Information Services Data Quality

4.4.4 Summary of Policy Issues and Considerations

4.5 Other Private Sector Trends

Appendix A – References and Resources

Appendix B – Web Survey Questions

List of Acronyms

AAA – American Automobile Association

AASHTO – American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials

ADOT – Arizona Department of Transportation

ATIS – Advanced Traveler Information Services

ATMS – Advanced Traffic Management System

CAD – Computer Aided Dispatch

CARS – Conditions Acquisition Reporting System

DMS – Dynamic Message Sign

DOT – Department of Transportation

EMS – Emergency Medical Services

FDOT – Florida Department of Transportation

FHWA – Federal Highway Administration

GPS – Global Positioning Satellite

HTCRS – Highway Travel Conditions Reporting System

ISP – Information Service Provider

ITIP – Intelligent Transportation Infrastructure Program

ITS – Intelligent Transportation Systems

IVR – Interactive Voice Response

KDOT – Kansas Department of Transportation

MDI – Model Deployment Initiative

MDOT – Michigan Department of Transportation

MoDOT – Missouri Department of Transportation

MTC – Metropolitan Transportation Commission

NJDOT – New Jersey Department of Transportation

ODOT – Oregon Department of Transportation

PDA – Personal Digital Assistants

PND – Personal Navigation Devices

RDS-TMC – Radio Delivery Service -Traffic Message Channel

SAFETEA-LU – Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users

SANDAG – San Diego Association of Governments

TTI – Traffic and Travel Information

UDOT – Utah Department of Transportation

VAR – Value-Added Resellers

VDOT – Virginia Department of Transportation

WAP – Wireless Application Protocol

Executive Summary

Partnerships for traveler information systems and services have been in various stages of evolution, cooperation, and functionality. Traditional public-private partnerships for traveler information have typically consisted of public agencies serving in a data collection role (through manual and automated systems) and making use of data collection infrastructure and systems that were initially designed for traffic management and operations purposes.

This State of the Practice Review documents a range of business models for real-time traveler information services, and provides ‘real world’ examples of how States and regions are developing partnerships and business plans within the business model frameworks. Although there are numerous variations on the more traditional models, there is no question that there have been shifts in the fundamentals of these traditional business models, as well as new business model structures that have emerged.

Key shifts in both the public sector arena as well as the private sector marketplace are evident in the current business models and partnerships for traveler information services. On the public sector side, the most notable shifts have come about largely due to the increasing role of public sector for traveler information. 511 phone and Web services, largely spearheaded by public sector, have put a very recognizable brand on traveler information. Furthermore, as public sector system operations become more integrated, traveler information is no longer a stand-alone function. Closely linked are operations, maintenance, incident management, public transportation, weather monitoring and multi-agency coordination—all of which have strong ties to traveler information—and the public sector is looking for creative ways to leverage its investments. Public agencies are taking on more responsibility for aggregating data to support systems that provide more robust and comprehensive information to travelers. Several public sector agencies are also developing innovative applications to deliver personalized and enhanced information to travelers, either through Web-based resources or through ‘push’ technologies, such as alerts delivered to mobile phones. This is an area that was once thought to be under the private sector commercial services umbrella.

Roles for private sector are also shifting. Early traveler information models focused heavily on the private sector leading efforts for data fusion and dissemination. While these may still be the case, there is increased activity on the private sector side for data collection, including infrastructure-based, probe vehicle data, and aggregated, multi-source data. In an effort to be able to expand upon what is currently available from public sector data collection infrastructure, the private sector is looking at innovative ways to obtain data over broader geographic areas. This shift has turned the public sector into a potential consumer for private sector data. It has also put an important responsibility on the public sector to be able to safeguard commercial value of private sector data and services. Some of the most successful private sector models are ones that have multiple levels of revenue potential; in other words, there is a need for the private sector to look at the range of potential consumers—the public, other private sector companies, as well as the public sector.

The private sector continues to pursue good models, and there is continued interest in subscription services, as evidenced by the growing number of partnerships to combine real-time traffic data with navigation applications, either mobile or in-dash units. Subscription models are not without their challenges, and despite growing interest in personalized mobile applications, there is still a need to balance the threshold of what consumers are willing to pay for traffic information. Media continues to be a powerful private sector partner for traveler information, and with media comes a range of potential business model options and business-to-business partnering opportunities.

From a regional traveler information program perspective, the most sustaining model is one that has significant resources, leadership and investment from the public sector. Whether public-sector operated or through contracted operations with the private sector, the need for public sector financial resources for traveler information is not diminishing.

Traveler information business model approaches developed over the last decade saw very clear roles for the public and private sector in terms of data collection, data aggregation, data fusion, information dissemination, and key steps in the process where private sector would be able to monetize their product or services. With the evolution of technology, raised awareness of traveler information among the public, creative partnering approaches from both the public and private sides, and a strong push toward broader coverage of traveler information programs and enhanced accessibility for users, there have been distinct shifts in these roles. This State of the Practice Review documents many of these shifts and provides an overview of current trends and issues with traveler information business models.

Section 1. Introduction and Project Overview

1.1 Context for the 2007 State of the Practice Review

For more than a decade, partnerships for traveler information systems and services have been in various stages of evolution, cooperation, and functionality. Traditional public-private partnerships for traveler information have typically consisted of public agencies serving in a data collection role (through manual and automated systems) and making use of data collection infrastructure and systems that were initially designed for traffic management and operations purposes. Recognizing that this operations data could support a key service in providing road and travel conditions information to motorists and travelers, the public sector made additional investments in ‘push’ technologies and infrastructure to disseminate information via dynamic message signs (DMS), highway advisory radio and other means. Data gathered by the public sector was often provided to the private sector Information Service Providers (ISP) who would then disseminate information through a variety of systems, such as media traffic reports or through personal wireless and in-vehicle technologies.

Business models for traveler information have also been evolving to keep pace with technology advances, stronger focus by the public sector on integrated operations and customer service, as well as with the increased consumer demand for more comprehensive and real-time information.

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is spearheading the development of an update to the Advanced Traveler Information System (ATIS) Business Models review prepared in 2001 to capture some of the shifts and changes in traveler information business partnerships, identify which models have had the greatest success in terms of sustainability, and where there are innovative or unique models in place or on the horizon.

This State of the Practice Review takes a look at typical business models for real-time traveler information, and provides ‘real world’ examples of how States and regions are developing partnerships and business plans within these model frameworks. These frameworks were developed as part of previous efforts to begin to establish some guidelines and scenarios for how partnerships could be structured to support traveler information services. Although there are numerous variations on the more traditional models, there is no question that there have been shifts in the fundamentals of these traditional business models, as well as new business model structures that have emerged.

1.2 Summary of Contributing Factors to Changes in Traveler Information Business Model Approaches

A significant emphasis of this State of the Practice Review is to document the major influences and shifts that are occurring in business model arrangements for traveler information. One of the biggest influences in recent years, at least on the public sector side, has been the emergence of 511. With 511 phone and Web-based traveler information systems, there has been a noticeable surge in the public sector ownership and responsibility for traveler information, and for developing innovative fusion and dissemination strategies that were once thought to be under the private sector umbrella. In many areas, 511 has become synonymous with a regional or statewide traveler information program, and there are several references throughout this document that highlight innovative program aspects from a wide range of systems and regions.

At the national level, the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU) Section 1201 requirements as part of the recent federal transportation legislation are seen as a key driving force behind several public-sector initiatives, a key one being traveler information. There are efforts underway to be establishing a national ‘standard’ for data attributes relative to timeliness and time parameters for incidents, delay, and other key traveler information services components. These have implications that go much deeper than what information the user receives—they will require changes to how data is collected, by who, influence the aggregation/fusion process, and will have obvious impacts in terms of data sharing.

The impact of technology and advances in information collection and delivery mechanisms cannot be underestimated. From advances in data collection and the emergence of the private sector data collection options in recent years, to the widespread use of Internet and wireless mobile applications, supply and consumer demand are at historic highs. Conversely, the private sector is still trying to pinpoint where the consumer threshold is for a marketable, profitable subscription-based product. Many of the private sector organizations interviewed as part of this State of the Practice Review articulated that private enterprise is also looking for good models.

Furthermore, the private sector is not just marketing directly to the end user consumer. In fact, the public sector is also a potential consumer base for private enterprise. Supply chain theories apply to traveler information as well, and many of the products and services we use for traveler information on mobile phones, in-vehicle devices or even Web sites require several layers of partners to deliver. The business-to-business relationships are evolving along with the potential business models.

1.3 Methodology and Approach

The study team relied heavily on input from both the public and private sectors to be able to capture the current approaches and issues with business models and business model arrangements for traveler information. Three key methods were used to obtain information and real-world experiences:

-

Literature review of available documentation, including traveler information business plans, strategic plans and program descriptions. Also included with the literature review were previously developed documents that focused on traveler information business models, data quality and data reporting systems. Agency Web sites and performance monitoring plans were also reviewed. A list of resources and literature obtained during the course of this study is included in Appendix A.

-

Web-based survey. In December 2006, a Web-based survey was distributed to the public sector traveler information contacts in an effort to obtain a wide cross-section of input about their traveler information program partnerships, involvement of the private sector, data sharing arrangements, and innovative approaches. A list of the questions that were included in the Web survey is included in Appendix B.

-

Interviews. Phone and in-person interviews were conducted with several representatives from the public sector and the private sector regarding traveler information services. These included regional and statewide traveler information systems operated by the public sector, as well as a wide range of companies from the private sector representing data collection, dissemination, and system operators/developers.

Section 2. Background and Historical Context

2.1 Early Traveler Information System Business Model Approaches

The basis for many of the past and current traveler information business models and business partnering approaches was a two-part series from ITS America, “Business Models for Advanced Traveler Information Systems Deployment” (1997) and “Choosing the Route to Traveler Information Systems Deployment: Decision Factors for Creating Public-Private Business Plans” (1998). These guidance documents provided a succinct overview of some of the key policy, partnering, planning and system development issues that the public sector could expect to encounter (or at least consider) as it moved toward a more business-based approach to traveler information systems. The ‘big five’ business model arrangements, shown below in Table 1, described roles and responsibilities for various partners under the different partnering arrangements, but were general enough to accommodate variations.

Table 1 – Early Traveler Information Business Model Frameworks

|

Public-Centered Operations |

|

Least Risk

Least Potential for Revenue

Higher Risk

Higher Potential for Revenue |

||||||

|

Contracted Operations |

|

|||||||

|

Contracted Fusion with Asset Management |

|

|||||||

|

Franchise Operations |

|

|||||||

|

Private, Competitive Operations |

|

|||||||

When these model approaches were developed in 1998, there was a distinct emphasis on urban area, regional traveler information services. These were the areas that were likely to have data available from the public sector, as well as a target market of commuters that would find value in accurate, timely, and relevant information about road and travel conditions.

The challenge almost a decade ago was that there was limited case study material available. Many regional traveler information programs and systems were just emerging, as were the various partnerships among the public and the private sector. The private sector marketplace was also somewhat emerging, and as demonstrated by the above models, relied on a ‘traditional’ relationship of the public sector collecting data, and the private sector having the technology, resources and interest in performing the data fusion and dissemination functions. There were very few proven success stories in terms of business models and business arrangements, largely due to the maturity level of the traveler information service marketplace. Technology and applications were emerging at a fast pace, and with them came a plethora of ‘potentials’. Many of the early implementations as part of the Metropolitan Model Deployment Initiatives (MDIs) and other traveler information services were quite experimental, from technology, consumer acceptance, and longevity standpoints. Widespread usage of the Internet and wireless technology had not yet emerged as a market focus area. As a result, initial costs and risks for technology applications and demonstrations were high, which impacted the public sector as well as the private sector. Media (television and radio) was viewed as a strong partner on the private side, and there was often a direct relationship between DOT and media for information dissemination.

A 2001 report titled “ATIS U.S. Business Models Review” documented how the market and business models were actually developing, and took a critical look at 10 regional markets. Some of the key conclusions and findings based on discussions from the public sector and the private sector perspectives included:

-

The public sector support is essential to successful traveler information service implementation. Successful, sustaining systems have significant involvement from the public sector in data collection as well as fusion.

-

Models that relied on the private sector generating revenue to offset public costs or sustain operations of a regional traveler information service had not proved successful.

-

Customer threshold and willingness to pay for traveler information was not yet proven.

2.2 Lessons and Experiences from European Models

Although the focus of this State of the Practice Review is on traveler information service business models in the United States, there are some benefits to looking beyond the domestic models and approaches for lessons, practices and policy issues from European approaches that could potentially be applied here.

A 2002 scanning tour comprised of FHWA, American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), Federal Transit Authority, State DOTs and the private sector toured eight European cities with established, multimodal traveler information programs. From a business model and partnering perspective, there were some key similarities in terms of policies and approaches. Both European and US practices recognize that a sustainable traveler information system requires multi-agency cooperation to develop, implement, and ultimately deliver for the long-term. In several areas visited there was strong reliance on the public sector for overall traveler information system funding, program management, data collection and information dissemination. There were also very defined roles and contract arrangements. In Berlin, there were some emerging concepts and models for public-private partnering for traveler information that were very similar to approaches used in the United States (the public sector subsidizes initial start up and provides a basic level of information to the public, and the private sector generates revenue for sustaining operations through enhanced, value-added products and services and business-to-business arrangements).

The European Commission has publicly articulated very strong support for partnering among the public and private sector to advance and accelerate deployment of intelligent transportation systems (ITS) and programs, with a distinct emphasis on Traffic and Travel Information (TTI) throughout Europe. A 2001 Commission of the European Communities Report and Recommendation specifically outlined several key directives, which encourage public authorities to:

-

Allow the private sector to deploy and operate their proprietary traffic monitoring equipment on public roads;

-

Adopt measures to ensure that public authorities “safeguard the commercial value” of proprietary traffic data received by private service providers; and

-

Ensure that the private sector TTI service providers have flexibility to develop and distribute travel information products and services on a commercial basis, providing they do not impact safety, traffic management, or jeopardize privacy and personal data.

This policy-level recommendation and provisions for establishing the public/private framework is a bold recognition by the European Commission about the value in public-private partnering for traveler information.

Key differences include the prominence among European systems for multimodal and route-planning applications. Examples include the Berlin Model (www.vmzberlin.de) as well as the United Kingdom’s www.TransportDirect.com. Such robust, multimodal applications require substantially higher investments in data collection, multi-agency coordination and system management and oversight than what is typically found in US-based traveler information tools (although there are exceptions). This level of data collection and coordination also points to a significant investment from the public sector for the up-front activities and operations, which is not unlike how most business model approaches in the US currently operate.

2.3 National Guidance Promotes Quality, Consistency in Traveler Information Services

One of the keys to defining and developing good business models is to have a clear foundation of system capabilities, expectations, and performance standards. As systems throughout the country have evolved, become more technology focused and integrated, and with an increased focus on bringing multiple data sources together to support a comprehensive program, defining quality and consistency expectations has become increasingly important, and is an area where there has been national leadership from FHWA, AASHTO, ITS America, and others.

“Closing the Data Gap: Guidelines for Quality Advanced Traveler Information System Data” began articulating some of the critical features, attributes and quality parameters that should be factored in to traveler information services. Attributes include such characteristics as timeliness, accuracy, cost (to use) and reliability were identified as important factors for users. These guidelines also outlined some very definable and measurable parameters for various data types, which put some very specific attributes to the myriad of data that could be incorporated into a real-time traveler information system. Attributes such as accuracy, detail, breadth of coverage and others provided at least a baseline for establishing what could constitute ‘quality’ data—a definite benefit for either public or private interests. What this provides to the business model and developing the partnerships within the model is a common framework for how to articulate system expectations.

When the 511 Coalition published its national guidelines, the intent was to promote some consistency among the individual systems that were being implemented throughout the country. What began as a means of providing guidance on what should constitute ‘basic’ and ‘enhanced’ content for 511 has evolved into a tool for deployers to use to address nearly all facets of system deployment, operations and marketing. Potential business models for 511 services were also developed, and were somewhat based on the ‘big five’ traveler information business models developed in the 1990’s, but were modified to address the service-specific nature of 511 phone traveler information services. These included:

-

Public sector funded;

-

Subscription model;

-

Pay-per-call model (conflicts with Coalition guideline of no more than the cost of a local call);

-

Advertising and sponsorship model;

-

Loss-Leader/Franchise model; and

-

Hybrid model, to allow a combination of approaches.

The guidelines and the potential 511 business model approaches developed in the early years of 511 implementation were geared toward the phone component, and did not really factor in the traveler information Web site. The intent was to provide deployers with options for flexibility in how they structured a (potential) cost recovery mechanism and partnerships as part of 511. To date, the model for nearly every 511 program in operation is the public sector funded. It should be noted that there are some emerging regional 511 services offered through the private sector; however, these services also follow the guiding principle of ‘no more than the cost of a local call’ for users. The prevailing theme, which has been echoed across numerous traveler information business models, is that the most successful and sustaining are those with significant support and resources from the public sector.

Section 3. Predominant Traveler Information Business Models and Issues

This section illustrates the typical traveler information business model structures, and presents case studies of how regions and agencies have developed traveler information programs within a business model environment. Included is discussion about the fundamental structure of business models, as well as some variations, and ‘real-world’ examples of how these business models are currently working. Issues and challenges that are inherent in the business model approaches also are presented.

3.1 Public Sector-Funded

To date, this is still the most sustaining and successful model for delivery of regional traveler information. The term ‘regional’ is no longer limited to urbanized areas; traveler information programs a decade or more ago focused primarily on data-rich urban environments. With the emergence of 511 and with strong leadership from the public sector to provide traveler information on a statewide level, the focus of traveler information has also broadened in scope for many areas. State DOTs are making significant investments in data collection and reporting systems, establishing partnerships for additional data (such as with public safety for incident information), as well as investing in phone and Web-based dissemination tools, which were once thought to be primarily a responsibility of the private sector.

The public sector operated/funded model generally falls into two categories which rely heavily—if not solely—on funding from the public sector for key operational areas of their traveler information programs. Table 2 provides a comparison of these two approaches to the public sector funded model.

Table 2 – Comparison of the Public Sector Funded Approaches

|

Public Centered Operations |

Contracted Operations |

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Examples: AZTech™, Phoenix, AZ Kansas DOT (Statewide) Oregon DOT TripCheck |

Examples: MTC, San Francisco Bay Area, CA Tampa Bay Area, FL (511 service) Florida DOT Statewide (iFlorida) |

||||||||

While this model requires a substantial amount of funding, leadership and involvement from the public sector, there comes with that a certain level of ‘control’ over the traveler information program. With public funds and contracting mechanisms in place, the public sector can be very specific about data, quality and performance expectations. There is also a certain amount of longevity and sustainability that comes with the public sector leadership and ownership.

75% of the agencies surveyed for this Review stated that involvement from the private sector has not diminished the public sector responsibility for their traveler information programs.

Another advantage of this model is that there is flexibility to be able to tap specific expertise from one or more partners from the private sector to address certain pieces of the traveler information program—such as expanding data coverage by supplementing with the private sector data, or perhaps contracting with a private sector provider to operate a key dissemination outlet (such as phone, Web or both). Kansas DOT (KDOT) indicated that as part of their traveler information program strategic planning process, they took a hard look at what they really wanted to provide to the public, identified what the department could realistically accomplish, and where it made sense to contract with a private partner for additional expertise and resources. The result is a strong KDOT-led statewide traveler information program that utilizes a private contractor for 511 operations (Meridian), and partnerships with a wireless telecommunications provider for kiosks.

3.1.1 Public Centered Operations

There are several solid examples of the public centered operations model, including both regional as well as statewide systems. These successful models include varying levels of involvement from the private sector, but they are not dependent on the private sector in a substantial operational role to where the traveler information program could not operate without their involvement. The AZTech™ program in the Phoenix metropolitan area of Arizona, and Oregon DOT’s TripCheck are featured below.

Arizona – AZTech™ Case Study

AZTech™’s traveler information business model has been evolving since 1996, when the FHWA MDI began in the Phoenix metropolitan area. A key objective of the MDI was to showcase innovative public/private partnerships for traveler information delivery. AZTech™ began with a very formal approach to partnering with the private sector, including issuing Requests for Proposals and developing formal contractual agreements with each of the partners. Between 1996 and 2005, AZTech™ went through three private partner phases. A key principal for each phase was that it would involve multiple non-exclusive arrangements – the AZTech™ partners did not want to limit or constrain their ability to capitalize on innovations from the private sector. Data would be made available to multiple private interests whereas early phases of the AZTech™ program required a contract to access data. This allowed the Arizona DOT (ADOT) and other partners to know who was accessing their information. With many more interests now wanting data, ADOT made the decision to do away with contract agreements for the private sector to access ADOT’s data feed, and instead make the data available via a file transfer protocol (FTP) site (registration required).

AZTech™’s first two phases saw a wide array of involvement from the private sector, which was focused primarily on disseminating traveler information. Kiosks, wireless application protocol (WAP) phones, handheld devices, in-vehicle devices and other technology applications that were part of the early AZTech™ MDI program eventually went by the wayside. These new technologies with limited deployment, limited regional focus, and business models that relied primarily on subscription services did not result in successful, sustaining deployments. The public sector data collection infrastructure was also limited during the early MDI phases, and consisted primarily of freeway sensor data on two freeway corridors. According to AZTech™, there is definitely some risk for early implementers. The public sector efforts were not necessarily impacted by the private sector turnover – AZTech™ public partners continued to focus on data collection and dissemination through the traditional public channels (media partnerships, roadside infrastructure, etc.).

Data collection has been primarily a public-sector responsibility for the AZTech™ traveler information program, and AZTech™ partners are continuing to put a strong focus on improving data collection. In recent years, two key partnerships with the State Department of Public Safety and Phoenix Fire (who dispatches for nearly 20 fire/emergency medical services (EMS) response agencies in metropolitan Phoenix) are providing real-time incident data via a computer-aided dispatch (CAD) feed. AZTech™ estimates they now have knowledge of 80% of incidents in the metropolitan area that impact the arterial network; previously, this arterial information was extremely limited. AZTech™ partners have essentially evolved into a data aggregator, and ADOT and the Maricopa County DOT have taken on a large responsibility to consolidate traffic, incident, weather and event data into a robust database that serves the Phoenix and Tucson metropolitan areas as well as statewide corridors. Arizona’s 511 service (phone and Web) is also operated and maintained in-house.

Oregon – TripCheck.com Case Study

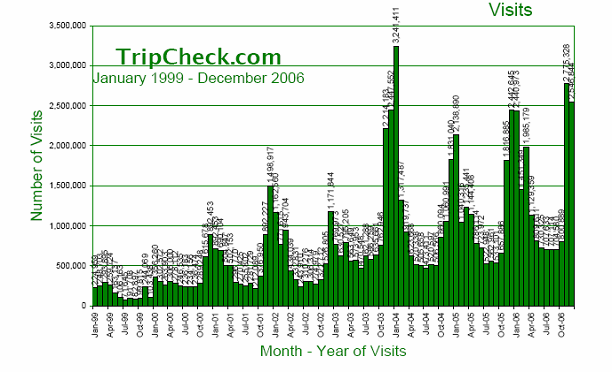

TripCheck has become synonymous with traveler information in Oregon. Developed (and currently operated) in house by the Oregon DOT (ODOT), TripCheck was launched in 1998 as a Web-based tool for road conditions, closures, and in particular winter road closure information for Oregon’s statewide highway system. ODOT partnered with the Oregon Travel Information Council (TIC), a “self-funded state agency” which manages the interstate and off-interstate logo sign program. The blue highway signs provide directional information to traveler services (gas, lodging, food, camping and attractions). Through this partnership, ODOT received a percentage of the revenues generated from the logo sign program to help fund TripCheck development and operations activities.

Since the initial launch, ODOT has been incrementally enhancing the TripCheck.com Web site to be able to provide enhanced urban area information (cameras and event information), statewide weather, and traveler services. A substantial upgrade to the system was launched in 2005, and included a major revamp to the Web site, alert information, enhanced functionality and traveler services information. A continued partnership with the TIC facilitates hotels, restaurants, and other businesses to be listed as part of TripCheck.com.

Although ODOT also operates a statewide 511 phone service, and has co-branded 511 with TripCheck. The TripCheck.com Web site was already a well-recognized brand for traveler information in Oregon, and with the implementation of 511 and the transition away from the previous toll-free hotline, ODOT was able to bundle both phone and Web under the TripCheck brand.

3.1.2 Contracted Operations

The other facet of the public-sector led traveler information program is where a private sector entity is contracted to serve in a significant operational role – whether it is to support or lead data collection, information aggregation or information dissemination. For this model, the private sector serves under a termed contract in a fee-for-service arrangement. The public sector still serves in a leadership and operations role, but contracts with the private sector to serve in a specific function.

There are several variations on this model and arrangement, and roles for the private sector will vary depending on the specific needs of the public sector and the niche that private sector can address. Table 3 below broadly identifies potential roles for the private sector to participate in a regional traveler information system as part of a contracted arrangement.

Table 3 – Private Sector Contracted Operations Roles

|

Data Collection |

A surge of data collection companies have entered the market in recent years. Some, such as SpeedInfo, Traffic.com and TriChord, gather data through their own roadside infrastructure, and sell that data to the public sector and other private entities. Emerging technologies, such as cell phone/travel time data collection strategies, are still under development and in the early implementation stages. Section 4.2 provides additional details. |

||||||||||

|

Data Provider (Aggregated) |

Traffic.com and Inrix are two examples of data providers that are also data aggregators – they gather data from a variety of fleet, the public sector, and other sources to provide a data feed with speed/flow (which includes real-time and predictive) as well as incidents. Although the public sector is a source of data to this feed, the expanded data coverage provided by their other sources also makes the public sector a potential consumer. These providers of aggregated data also serve other private sector entities (such as media, in-vehicle navigation system operators, and other ISPs) in the traveler information arena. Their customer base is broad – they can be a resource to both the public and private sectors to support a range of information dissemination methodologies. |

||||||||||

|

Information Dissemination |

Perhaps the most prominent of the public/private partnerships for traveler information is in contracted operations for information delivery. 511 has seen an increase in contracted operations – several private entities are involved with developing and operating 511 Interactive Voice Response (IVR) phone systems. Virginia has a unique arrangement with TrafficLand to coordinate dissemination of Virginia DOT’s (VDOT) video images through Web and broadcast media. |

||||||||||

|

System Development and Operations |

This category would include contracted operations to develop or operate elements of the traveler information system, such as the data fusion engine, a database or reporting system, or other critical element. |

||||||||||

The contracted operations approach has several advantages:

-

The public sector still has a strong role and direction in the program. Even with the private sector supporting some operational aspects, it is still viewed as a public system, and with that comes stronger accountability on the part of the public sector.

-

The public sector can contract with one or more private entities to provide specific services – this provides a level of flexibility, while allowing the public sector to expand or broaden its traveler information services. Contracts/agreements also provide some level of risk management.

-

The public sector leverages the strengths of the private sector in terms of bringing innovative approaches and cost sharing from other cities/States.

Risks with this approach can be minimized through contracts and agreements. These are more prominent in ‘for fee’ services; with zero dollar agreements, there is a risk of less incentive for the private sector. These of course depend on the nature of the services – data and systems provided by the private sector are typically considered a commodity or service to which a monetized value can be attached, as well as performance metrics. If the contractor is not performing, the public sector can take action by enforcing contract terms or getting another contractor. Contracts can also specify quality parameters for data, service, system reliability, and other attributes.

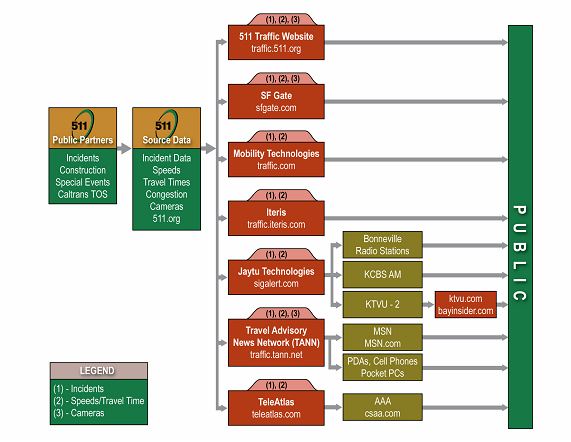

Metropolitan Transportation Commission, San Francisco Bay Area – 511 Contracted Operations Case Study

The Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) in the San Francisco Bay Area uses this model to contract with a system manager/operator for comprehensive operations of their traveler information system. In fact, MTC maintains several subcontracts to support various components of their 511 program (this includes the private sector data collection contracts, Real-Time Transit information system development, marketing). Telvent Farradyne, the primary operations contractor that operates the Traveler Information System, developed the TravInfo database, as well as the IVR system and Web. Telvent Farradyne operates and hosts the system, and is responsible for ongoing operations, enhancements and expansion. Coordination with other contractors and agencies is essential in this role, because MTC’s multimodal system includes traffic conditions information, transit, rideshare, bicycle, and planned event data. Each of these modes utilizes different contractors to support different pieces of the system. Even with significant contractor support, MTC staff is integrally involved in day-to-day operations and management, and has a very strong focus on strategic planning. The Bay Area 511 is undoubtedly the most robust system of its kind; MTC has made a significant investment in this regional system, dedicating approximately $4 million per year.

MTC has stated they prefer long term contracts – there is more continuity, less risk, and longer-term contracts minimize the need to go through a complex procurement process on a regular basis. The trust and synergies developed between contractors and MTC staff cannot be underestimated. Furthermore, longer term contracts lead to better short- and long-term planning. The MTC system has been evolving for a decade, and the ability to strategically plan for enhancements—particularly with such a complex and intertwined system—has been a key to the success and ongoing evolution of this robust program.

Florida – Contracted Program Elements Case Study

Florida DOT (FDOT) contracts out various portions of its ITS program to several private sector firms. As part of the iFlorida consortium, Castle Rock developed and maintains the Statewide Conditions Acquisition Reporting System (CARS), which is the statewide repository of incident, construction and special event information that feeds the Statewide 511 system. They have a contract with PBS&J and Southwest Research Institute to develop and maintain the advanced traffic management system (ATMS) software and data fusion engine, which calculates the travel times from sensor and toll tag data in Orlando. In addition, FDOT has a contract with TMI (Traffic Management, Inc.) to operate its Orlando traffic management center. A firm called Logic Tree has a contract to provide and maintain the platform that runs the 511 phone system. FDOT also contracts out maintenance of field devices.

FDOT sees traveler information services as a public sector responsibility, but recognizes that it must leverage the expertise resident in the private sector to produce a quality product. Each of the firms they contract with has a certain expertise that together provides the complete traveler information service to the public. In the end, however, the public sector has a responsibility to ensure traveler information services are available and the best way to do that is to serve as its own general contractor for all the pieces that need to be in place.

Florida DOT District 7 – Traveler Information Program Case Study

FDOT District 7 (Tampa Bay) contracted out its traveler information services to Traffic.com in 2004. They have a separate contract with Traffic.com through the Intelligent Transportation Infrastructure Program (ITIP), which will be discussed in section 4.2.1. Unlike ITIP, this is a typical contracted operation, awarded out of a competitive selection process. FDOT pays Traffic.com an annual fee to run and maintain the 511 system, and paid an additional first year amount to design and launch the system. The contract has a set expiration date (August 2008), after which time District 7’s 511 system will merge with the statewide system. In addition, District 7 has a new traffic management center that is ramping up operations and will run the Statewide ATMS software. The benefit to contracted operations in this case, is the ability to establish a contract for a specific period of time, after which the agency can adapt to a changing direction, in this case a statewide initiative unifying the Districts under a common traffic management platform.

3.2 Franchise Operations

This model is another representation of a public/private partnership – it relies on the private sector being able to support some or all of its operations for the traveler information system, or at the very least be able to offset the amount of public funds required to operate or deliver traveler information services.

Typically, this business model does provide for some flexibility in how the private sector accomplishes revenue generation – either through capital investors, usage fees (either for the end user or through fees charged to outside entities for use of the data), license fees or advertising. It should be noted that there may be some restrictions on advertising based on public partner policy, particularly if the program is under the guise of a ‘public sector’ system.

On paper, the franchise operations model seems like a viable idea: capitalize on the private sector’s innovation, resources, and ability to keep pace with technology while offsetting or reducing the public sector’s financial or resource obligations to support the system. With an environment that encourages the private sector to be innovative, there is an incentive for the private sector to be creative in how they approach developing their model.

It is important to note that the franchise model does not necessarily diminish the role of the public sector in the overall system development or delivery, but rather would allow the public sector to focus on elements of the operations program that it is already doing, such as operating freeway sensors and gathering that data or providing information to travelers through DMS. The private sector would then take on additional components of the system in an effort to provide a service while being able to generate revenue for its operations.

To date, there are few examples of this model in a sustaining environment. A key challenge that has hindered the success of this model is the fact that most systems that tried to implement it did so on a regional basis. This means that there is a substantial investment required by the private sector to be able to develop and implement systems that focus on a narrow target audience within a region. Generating enough revenue to cover capital as well as operations costs becomes a challenge with a limited potential target audience.

Another challenge is that the majority of opportunities for revenue generation as part of a regional traveler information system are on the dissemination side – whether by charging fees directly to users or by charging access/license fees to other public and private entities for access to data, video or other information. In order to effectively do this, there needs to be some element of exclusivity, otherwise where is the incentive to pay? Many public sector agencies willingly provide data to multiple public and private partners as a means of utilizing various avenues to get the information to consumers. Information is freely available to consumers via radio, television, phone and Internet, which in most areas could limit the ‘exclusivity’ factor. Later sections in this document point to some successful private sector models, but the majority of revenue generation to sustain and expand operations did not come from one-to-one user fees, rather it is due largely to a combination of revenue streams – the most predominant being advertising revenues – and multiple layers of potential consumers (users, other ISPs, and even the public sector) that point to a sustaining and successful model.

An overarching business model question which impacts nearly every potential model, but particularly those where the private sector is trying to earn a profit, is ‘where is the consumer threshold for their willingness to pay for traveler information?’. This threshold relates to price, but also to the quality of the information, the extent of coverage (e.g., does it include arterial streets?) and how is that information delivered (e.g., in my car, on my computer, on my radio?). These are questions the private sector has been trying to answer for some time.

Although this model has not seen a tremendous success in terms of sustaining operations, the public sector continues to seek out ways to involve the private sector, deliver a good system that their users see as beneficial, as well as be mindful of limited agency resources and funds. Two examples of this approach are featured below: VDOT and San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG).

Virginia DOT Case Study

VDOT, through various partnerships, has been through three iterations of a model that would provide traveler services as part of phone and Web-based traveler information systems. The approach behind these models was that a combination of road and travel conditions, tourist destinations, traveler services and amenities and other information would be packaged and made available to travelers through phone and Web outlets. To accomplish this, the public sector (VDOT and Virginia State Police) would provide the road/travel conditions information, and the private sector would provide the traveler services component. Initiated as part of the I-81 corridor traveler information program (originally Travel Shenandoah), it was a region-specific system focusing on southwest Virginia. The private partner would be responsible for identifying potential hotels, restaurants, attractions, and traveler services that would want to have their business featured as part of the site. This required a sales staff to bring in business and a range of advertising ‘packages’ that potential advertisers could choose from. Their business would be featured on the Web site, be accessible from the phone service, and ideally these advertisers would also help to promote the service by displaying flyers, rack cards, and other promotional materials. The public sector would support some pieces of the operation, but ultimately there was an expectation that the private sector would generate enough revenue through Web space/advertisement sales to offset the public sector investment. In talking with VDOT, there were several challenges with this approach:

-

The product and system were still under development when the partners were trying to garner advertising support. Some pieces of the overall product were not yet in place (such as full telecommunications carrier support, signage not fully deployed), and proved to be a challenge selling an evolving product.

-

It was difficult to quantify to the small businesses and hotels along the corridor the impact of their advertising dollar. Unlike radio and other media that can point to listener base demographics and size, the sales staff was not able to articulate just how many customers their advertising dollars would reach. It is important to keep in mind that many of the potential advertisers in the I-81 corridor were small businesses with limited advertising budgets.

When the I-81 service expanded to a statewide 511 service, VDOT tried a similar model with a contractor and issued a requirement that the service be ‘free’ to the department. VDOT and Virginia State Police would continue to provide data through the Virginia Operations Information System (the Statewide incident database), but developing a model to generate revenue to sustain operations would be the responsibility of the private sector. For the Statewide service, the focus was again on the traveler services component. VDOT and the contractor agreed to evaluate project status after one year to see if the model was viable. Ultimately, VDOT decided to phase out the traveler services component as it was not generating enough revenue to offset the public sector costs for operations.

San Diego – Traveler Information Partnership Case Study

SANDAG recently launched a regional traveler information system as part of a public/private partnership with Telvent Farradyne. SANDAG’s partnering strategy is to develop and operate a regional traveler information system that includes publicly funded components as well as privately-funded components. Public funds are intended to be assets that assist with the program start up. The intent is to have two parallel activities:

-

The first is a Baseline Traveler Information Program, which includes phone, Web and a 511 Broadcast Services component. This baseline level of information would be available to users consistent with the 511 national guidelines of being ‘no more than the cost of a local call’.

-

The second, and where the private contractor has an opportunity for generating revenue is through the 511 Business Services. As part of this model, the contractor has exclusive use of real-time data as well as authorized use of the SANDAG 511 brand. The contractor can use data and the brand to develop business strategies with media, ISPs and others to generate revenue capable of sustaining operations. This could include dissemination agreements, additional levels of ‘exclusivity’, and business-based services that could potentially generate operational revenue.

SANDAG’s regional traveler information program covers San Diego County, and was launched in February 2007. The agreement with the contractor covers a three year period, at which time it will be reviewed for the option to extend. At the time of this writing, there is not yet an indication of how this model is working compared to the initial vision, as well as if there are enough opportunities for revenue generation to support contractor operations.

3.3 Private-sector operated and funded models

In addition to the public sector-oriented business models, there are the private sector business models that operate without direct funding from the public sector. These business model approaches that are funded and operated by the private sector can take different forms, including:

-

The private sector operating substantial portions of a region’s traveler information service without public sector funding;

-

Free traffic services supported by advertising;

-

Subscription models; and

-

Free basic information with premium services available for a fee.

3.3.1 Private sector operations without funding from the public sector

Examples of this type of business model include arrangements where a 511 service is completely outsourced to a private traveler information services firm. Whereas 511 services are typically contracted to the private sector with the public sector funding as in the Florida District 7 example cited previously, Missouri DOT (MoDOT) has opted to route 511 calls in St. Louis to Traffic.com’s phone service. Traffic.com already had a presence the St. Louis area as part of the ITIP program, as well as deploying additional sensors through a competitively awarded contract. MoDOT operates a Web site for St. Louis traffic information, but did not have the phone component in place. About ready to undertake a large design-build project on a key interstate, MoDOT chose to accept Traffic.com’s proposal for a free 511 regional service as a pilot program. While this arrangement does not cost the department any money, there is still a definite business arrangement. MoDOT holds an asset that has definite value to a traveler information services provider: 511, a Federal Communications Commission-allocated and nationally branded telephone number. In exchange for yielding the rights to this number, MoDOT receives a legitimate traveler information service for its constituents. Traffic.com receives phone traffic, which translates into Web traffic, enabling it to earn advertising dollars and promote its brand.

In another example, the American Automobile Association (AAA) Michigan operates a hotline and Web site with road and travel conditions in the State of Michigan. The Michigan DOT (MDOT) also operates a Web site, but there is not a statewide phone number for road and travel conditions. AAA Michigan operates a call center that accepts traffic/incident report phone calls from commuters, other agencies and field personnel. They also monitor the MDOT Web site, public safety scanners and coordinate with regional media to provide updated information on their Web site as well as through their toll-free hotline, which is updated daily with recorded messages. AAA Michigan also provides recorded radio spots with traffic and weather updates, and these are aired by radio stations throughout the State. By operating the Web site and phone, AAA Michigan has an opportunity to promote their services, which include trip planning, insurance, and AAA memberships. Unlike most statewide traveler information systems which rely on automated database feeds to phone or Web media, AAA Michigan staffs a customer service center that continuously monitors available information resources and updates the AAA Michigan information accordingly. MDOT does not contract with AAA Michigan to provide this service – AAA Michigan does so as part of its Michigan business practice.

3.3.2 Free services supported by advertising

These business models seek to earn advertising revenue from traffic services that are otherwise free to the user. The most longstanding and successful traveler information business models—broadcast media traveler information—belong in this category. Radio traffic reports in particular, are commonplace and produce sustaining revenues.

This model has been translated to the Internet. Web sites or email services that allow users to subscribe to customized email or RSS alerts with congestion, incidents or transit information are available through several Web sites, ranging from local news media to national/global sites (such as Yahoo!, MSN, The Weather Channel, and others). On the local level, news media outlets often partner with national firms such as Maptuit, Traffic.com, Triangle Software (Beatthetraffic.com), Westwood One/SmartRoute Systems, or others. These alerts include an advertising banner in the body of the email or on the Web site. Typically, these services do not generate sufficient advertising revenue to be viable standalone business models and are usually just one component of a company’s overall business. Most private traveler information companies have some form of advertising model for their Web sites or other online offerings. Across all industries, not simply traveler information, the clear trend is that Web sites should be free. While there are still examples where this is not the case, for-fee Web sites are typically extensions of other subscription business models (e.g., Wall Street Journal Online, Consumer Reports). The traveler information industry has followed this trend. Online services that were once available by subscription only have become advertising-based as a means of generating revenue to support operations.

Traffic.com is one example. Previously, accessing online real-time traffic data required a paid subscription. That transitioned to a service only requiring free registration. Finally, in its current state, the Traffic.com Web site requires no registration except for “mytraffic” services that enable email alerts and customized page views. The Traffic.com Web site and emails include banner advertising. In general, Internet advertising business models have not yet been proven to be profitable, with the exception of sites that can generate enormous amounts of traffic, such as Google and Yahoo. Nonetheless, for Traffic.com, while these advertisements do not pay for all of these services by themselves, they are merely one source of revenue. One way in which Traffic.com attracts advertisers is by promoting the ability to air the same advertising on the radio, on a cell phone traffic report, on a mobile device, on the Web, etc. As a result, they offer advertisers the ability to reinforce their message repeatedly to the same customer via different media.

3.3.3 Subscription models

Historically, traveler information services business models that relied solely on consumer subscriptions for have faced some challenges. While surveys show that people want traveler information and value it, they are not typically willing to pay for it in the form of a monthly fee. This may be due to the amount of traveler information freely available to the user, either from traditional media (funded by advertising revenues) or public agencies (publicly funded), which leads paying consumers to demand additional value to warrant the fees they pay. These may take the form of enhanced delivery methods (e.g., to mobile devices over a wireless network) or information that is more accurate or that covers more roadways than what is otherwise provided for free.

Services that fall under the subscription model banner are wide ranging. They include in-vehicle and portable navigation devices (often referred to as Personalized Navigation Devices, or PNDs), Web sites and services that provide enhanced or personalized traffic and route information, and could also be extended to include satellite radio, although traffic information is one component to a larger suite of subscription-based satellite radio programming. Section 3.5 discusses some of the innovative partnerships among technology companies to bundle traffic information with other subscription services.

The challenges in the marketplace for this business model stems primarily from the high cost and difficulty in collecting and aggregating high quality traffic data. Trichord is a small firm that deploys sensors to supplement VDOT sensors on the major freeways in Northern Virginia. Its business model has been to add value to the VDOT sensors through supplemental data collection, data quality filtering and custom delivery of traffic alerts to customers and media outlets. In their experience, there is a small and demanding market for individual subscribers; however, this market is too narrow to provide a sustaining revenue stream. In addition, by their estimates, the marketing cost of acquiring a customer required three years of revenue to break even. In light of this, Trichord has begun to pursue additional markets and business models.

TrafficGauge is another example of a firm with a subscription service as a key portion of its business model. Started in 2003, it sells a handheld device that displays real-time metro area traffic maps. It is currently in three markets: Seattle, Los Angeles and San Francisco. They found that getting the data is difficult and customer expectations are high. In fact, TrafficGauge reports that renewal rates are extremely sensitive to data quality, and that the primary reason for losing subscribers is data quality. Because TrafficGauge mostly gets data only from DOTs, their coverage is limited to major freeways that are instrumented with detection devices owned and operated by the public sector. They do not supplement with additional data collection, though they do partner with private sector data collection firms, such as SpeedInfo in San Francisco. Their business model is to sell devices and service. They have three devices—one for each market. Their service costs $5-10/month. A lifetime program is available. Unlike most firms relying on subscription models, however, they have been able to earn a profit, mainly due to the low cost of their device and the fact that they handle the entire supply chain from data collection to delivery.

3.3.4 Free basic information with premium services available for a fee

A similar business model offers a basic level of information for free, but charges for premium services. Trafficland is an example of a company that employs this model. It specializes in the distribution and redistribution of traffic camera video and images. On the Trafficland Web site, a visitor can select a city and see the DOT cameras on the site. Trafficland has relationships with many different DOTs with varying levels of involvement. Their original business model was to be the sole source for video images—more of a retail model. Their Web site would draw traffic and they would earn money through advertising on the site. They also offer a premium service for a monthly fee, which allowed subscribers to customize camera rotations and groupings for their particular routes. This portion of their business, however, has plateaued. There are customers who like it and will pay for it, but overall the company admits that it has been a hard sell.

Similarly, TrafficGauge provides a free download from its Web site for real-time traffic and incident maps for 17 markets. A free beta program is also underway to provide real-time traffic maps for the same 17 metro area markets via mobile phone. Currently this program is free, but TrafficGauge has indicated that it will be fee-based following the beta test. At the core of the TrafficGauge business model is its hand-held device described in the previous section, but TrafficGauge has expanded its services to include the free real-time metro area traffic maps via PC desktops.

Beat the Traffic provides traffic information and graphics (suitable for television or Web traffic reports) to news media throughout the country. It also offers a free Web site for the public with speed and incident information for several metropolitan areas. In partnerships with State DOTs, Beat the Traffic also makes CCTV images available. While the public can access the Web for free, Beat the Traffic also makes a MyTraffic subscription service available for a $19.95 annual fee. Users can create routes, and MyTraffic will indicate how much of the route is covered by sensors, provides travel times, and also provides an option to receive alerts via mobile devices.

3.4 Value-added reseller models

Value-added resellers (VARs) include Inrix, Traffic.com and TrafficCast. These are firms that aggregate and fuse data and resell it. While the VAR model is primarily data aggregation, which is discussed in Section 3.4, this model is an emerging one in the United States. In addition to intelligently fusing data from multiple sources, a key component of the VAR model is the value-added portion. This can take different forms, including the ability to establish relationships with different data providers, the ability to merge disparate data sources (e.g., probe data and sensor data), the ability to screen a data stream for inaccuracies or outliers, or the ability to use statistical techniques to compensate for limited data density or coverage. In major markets, all VARs use the same core set of data from the public sector, so the value-added portion of their business differentiates themselves from their competition and warrants the fees they charge for their data. While all VARs employ these techniques in some form or another, TrafficCast in particular applies traffic prediction and modeled/simulated speeds for non-sensored roads to supplement its real-time data. This involves the merging of historical and real-time traffic data to compensate for a lack of coverage or probe density. The cost of data collection demands that firms make the most of the data they have through algorithms, filters or models.

While the VAR model is typically reserved for private sector firms, TRANSCOM is essentially a VAR. When its private partner opted not to continue, TRANSCOM took over the selling of its aggregated content to VARs, who aggregate data from multiple cities to sell it as content to device manufacturers, mobile service providers, etc. What sets TRANSCOM apart is the value inherent in its data feed, prompted by its operations and public safety activities, from its 16 member agencies. While nationwide VARs boast an aggregated feed from many of the largest metropolitan areas across the country, TRANSCOM maintains an integrated traffic and transit database in the largest and one of the most diverse metropolitan area in the country. Instead of trying to replicate and maintain this aggregated data feed, VARs may purchase it from TRANSCOM.

3.5 Business-to-business models

While the public sector remains the key player in traveler information services, the private sector has many business-to-business models along the supply chain of traveler information services from data collection to aggregation to dissemination. As in other industries, few firms can provide the full range of capabilities in a supply chain. Changes in technology have been a significant driver in the development of business-to-business partnerships and have introduced variations on the typical traveler information services supply chain shown previously. This section describes various business-to-business arrangements in place today and touches on emerging trends.

-

Broadcast traffic reports supported by private data collection. This is the traditional traveler information services business model, where a traffic information provider contracts with local radio or television stations to be their sole provider of traffic information. This has historically been dominated by Metro Networks, Shadow Broadcast Services and Clear Channel. Traffic.com serves this market as well. These firms collect their own incident and speed data and in many cases employ their own on-air personalities. The business model is supported by advertising dollars, which allow the local stations to pay for the traffic information. While there is typically a strong reliance on the public sector traffic, incident and construction data for these broadcasts, many firms have their own data collection infrastructure in place, which may include private planes and helicopters or a loyal network of commuters who call in to report their conditions.

-

Mobile devices. These models differ from the previous model because instead of relying on radio or television transmission media, they require an alternative method of delivery, which is typically a wireless network of some kind. For the current generation of smartphones, that wireless network is typically a cellular wireless carrier and the cost of transmission is bundled into a monthly service fee. As a result, these carriers have become an important link in the supply chain for traffic information.

For navigation systems, requiring business relationships with wireless carriers can be prohibitively expensive. Radio Delivery Service -Traffic Message Channel (RDS-TMC) is a technology being used by these devices. Based on a European standard, it defines standards for the delivery of map-based traffic information to capable devices of a sub-carrier band on FM radio. Within the United States, XM, Sirius, ClearChannel, Microsoft (via MSN Direct) and CBS Radio are all broadcasting RDS-TMC under subscription services. Personal Navigation Device distributors (such as Garmin and TomTom, as well as in-dash GPS unit manufacturers (after-market as well as automotive manufacturers) have established partnerships with those companies to be able to link the navigation devices to real-time traffic feeds, and as such, able to ‘bundle’ the traffic information as part of a broader subscription service. Earlier versions of the in-vehicle navigation systems (as well as the wireless communications capability) were not well-suited for displaying traffic, but as technology and wireless communications improve, so do the opportunities to expand the visual capabilities of these systems.

Another business component to the mobile device market is mapping on which to display the traffic information. In this arena, Navteq and TeleAtlas hold a large market share for digital maps. These firms maintain up-to-date map databases that include new roads and interchanges as they are built across the country. A relatively new industry, standards to define how data is mapped are lacking. The two mapping firms have created de facto standards, though they differ. Nonetheless, recognizing the need to increase market share, they have developed translation codes to convert data between formats.

-

Internet. Besides broadcast traffic reports, the Internet is the most longstanding medium for delivery of traveler information. The business-to-business relationships present in Internet delivery are almost boundless. Like broadcast media, Internet traveler information does not require a proprietary network for transport, but it does typically require some kind of mapping. Current trends are heading toward more standardized mapping platforms, such as Google Maps, which uses Navteq’s road map database. The need to incorporate map databases will increase in proportion to the number of roadway miles covered by traveler information.

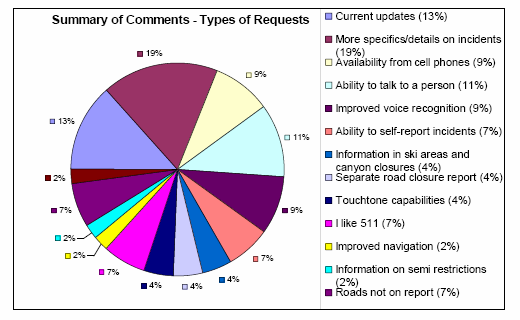

Section 4. Business Model Trends and Impacts