Regional ITS Architecture Guidance Document

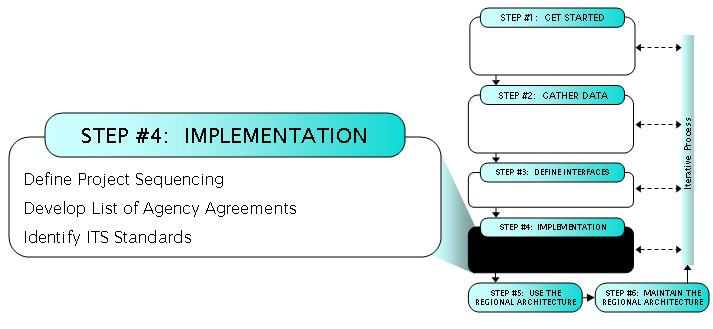

This section describes the "Implementation" step in the regional ITS architecture development process.

In the "Implementation" step, the regional ITS architecture framework is used to define several additional products that will bridge the gap between regional ITS architecture and regional ITS implementation. These products define the series of staged projects, enabling agency agreements, and supporting ITS standards that will support progressive, efficient implementation of ITS in the region.

In this section, the three "Implementation" process tasks are described in more detail. Each task description begins with a one page summary that is followed by additional detail on the process, relevant resources and tools, a general description of the associated outputs, and example outputs. Each task description also includes tips and cautionary advice that reflect lessons that have been learned in development of regional ITS architectures over the past several years.

| These tasks may be performed in parallel |

|

|---|---|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

|

PROCESS Key Activities |

Define Project Sequence

|

|

INPUT Sources of Information |

|

|

OUTPUT Results of Process |

|

The regional ITS architecture is "implemented" with many individual ITS projects and private sector initiatives that occur over years, or even decades. In this process step, a sequence, or ordering, of ITS projects that will contribute to the integrated regional transportation system depicted in the regional ITS architecture is defined.

One of the significant differences between ITS projects and conventional transportation projects is the degree to which information, facilities, and infrastructure can be shared between ITS projects. For example, a 511 Traveler Information System project may use information that is collected by previous instrumentation projects that collect traffic data and a CAD integration project that provides current traffic incident information. The regional ITS architecture provides a new way to look at these ITS project relationships or "dependencies". Project dependencies can be used to identify project elements that must be implemented before other projects can begin. By taking these dependencies into account, an efficient sequence can be developed so that projects incrementally build on each other, saving money and time as the region invests in future ITS projects.

Both the traditional planning process and the regional ITS architecture process have the same goal: to use a local knowledge, consensus process to determine the best sequence of projects to create a transportation network that best meets the needs of the people of the region.

A sequence of projects required for implementation is required in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)6 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.6.

A sequence of projects required for implementation is required in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)6 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.6.

Collect Existing ITS Project Sequencing Data

Projects are currently sequenced, or ordered, in planning documents like ITS deployment, strategic, or master plans that identify short, medium and long-term projects for a region. The TIP/STIP may include ITS related projects. At a higher level, long range plans may identify regional initiatives or priorities related to ITS. The first step in the ITS project sequencing process is to review these plans, identify the ITS projects that are already prioritized as short, medium and long term, and then use this as a starting point.

Beginning the ITS project sequencing task with the sequence already included in applicable transportation plans is the best way to make sure that the completed project sequencing product will be relevant to planners and factored into future transportation plans. This two-way relationship between the regional ITS architecture products and the applicable regional planning documents is critical to mainstreaming the regional ITS architecture into the transportation planning process. The relationship between the regional ITS architecture and the transportation planning process is described in more detail in Section 7.

Beginning the ITS project sequencing task with the sequence already included in applicable transportation plans is the best way to make sure that the completed project sequencing product will be relevant to planners and factored into future transportation plans. This two-way relationship between the regional ITS architecture products and the applicable regional planning documents is critical to mainstreaming the regional ITS architecture into the transportation planning process. The relationship between the regional ITS architecture and the transportation planning process is described in more detail in Section 7.

When a regional ITS architecture is updated, the same analysis applies. Review updated versions of the same planning documents that were used when the regional ITS architecture was originally developed. In particular, plan to update the status of projects as they are implemented over time.

Define ITS Projects

A regional architecture should identify projects to deploy the elements, services, and interfaces included in the architecture. The list of existing projects collected in the previous step should be expanded to cover the entire architecture. Prior to the development of regional architectures, some regions developed ITS Deployment Plans (a.k.a. Strategic Plans, Master Plans, etc.) to guide ITS deployment in the region. The Plans identified ITS projects for the region. The definition of projects in a regional architecture is similar to the development of such plans.

Since an architecture has a long time horizon, it may be difficult to define specific projects for the future, but nearer term projects should be defined in as much detail as possible so that they can flow directly into the regional programming or agency budgeting processes as discussed in Section 7. For nearer term projects, details of the project should be defined including the project location. While specific field device locations are typically determined later in the project development process, the project coverage area should be specified at the outset since this impacts project scope, cost, and project sequencing priorities. For example, a project for deployment of CCTV could be defined to cover specific corridor(s) of roadway(s) if the specific location of the cameras will be determined as part of the project.

For projects in the longer term, it may not be possible to identify specific projects but rather categories of projects such as "ramp metering installations", "transit and traffic management information sharing", and "evacuation management system". These categories or even larger groups of projects can be defined as regional initiatives which can be included in long range plans as presented in Section 7.1.

In addition to defining projects at differing levels of detail, it is important to realize that it may take a series of projects to deploy an ITS system. For example, a traffic management center (TMC) may require a project to plan the center including developing a concept of operations, a project to design the facility, and a project to construct it. As another example, ITS components such as surveillance cameras, message signs, signals, and ramp meters are not typically deployed across a region in a single project but in phases by roadway corridors. Since nearer term projects must feed into programming and budgeting processes, the phases of such projects should be identified in the project sequencing.

An architecture and the projects defined in it should not be fiscally constrained as in a TIP/STIP. An architecture is a plan for the future that would provide the ITS services desired for the region. The plan can be deployed as funding becomes available. It is critical not to plan and identify projects just for today's funding as funding availability varies due to policy changes and other issues.

Before the regional ITS architecture can be used to identify project dependencies, each ITS project must be defined in terms of the regional ITS architecture. This means that the ITS elements, the functional requirements, the interfaces, and the information flows from the regional ITS architecture that are relevant to the ITS project must be identified.

An ITS project typically provides a service or closely related group of services in a region. If an ITS project is easily represented by one or more market package instances that represent these services, it may simplify use of the regional ITS architecture in project documentation later. Defining ITS projects in terms of ITS elements, information flows, and functional requirements is part of the iterative development of the regional ITS architecture and maintenance of the architecture as discussed in Section 8.

The regional ITS architecture can be used to address many of the requirements associated with the systems engineering analysis for projects. Essentially, the part of the regional ITS architecture that will be implemented with each project is carved out, providing a head start for project definition:

The use of the regional ITS architecture to support ITS project definition is further discussed in section 7.

The systems engineering analysis required for ITS projects is defined in FHWA Rule 940.11 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 6.

The systems engineering analysis required for ITS projects is defined in FHWA Rule 940.11 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 6.

Evaluate ITS Projects

Each ITS Project should be evaluated in terms of anticipated cost and benefits and to determine whether there are any institutional or technical issues that will impede implementation. In addition, the evaluation may take into account agency and public support for each project and other qualitative factors that will impact the actual sequence in which projects are deployed. When updating a regional ITS architecture, cost estimates can be updated based on newer technology or investments that may not have existed when the architecture was developed or last revised.

Cost: Rough cost estimates for each planned project are an input to a realistic project sequence that takes financial constraints into account. Cost estimates should include both non-recurring (capital costs) and recurring (operations and maintenance) costs. Where possible, regions should use their own cost data as a basis. Cost basis information and assumptions should be documented to facilitate adjustment as additional data becomes available.

Benefits: The anticipated benefits for the planned projects can also be used as an input to project sequencing. An estimate of benefits normalized by anticipated costs is a common figure of merit that can be used to identify ITS Projects that are the best candidates for early implementation.

Both qualitative and quantitative safety and efficiency benefits may be estimated based on previous experience either within the region or in other regions that have implemented similar projects.

Technical and Institutional Feasibility: Each project can be evaluated to determine whether it depends on untested technologies or requires institutional change. Any impediments should be factored into the project sequence.

Documentation and tools are available to support analysis of benefits and costs to support ITS project sequencing. The USDOT JPO has an ITS Benefits Database and Unit Cost Database website that can be found at http://www.benefitcost.its.dot.gov/. In addition to the databases, the website contains several documents highlighting ITS benefits. A tool developed by USDOT is the Intelligent Transportation System Deployment Analysis System (IDAS), a sketch-planning software analysis tool for estimating the benefits and costs of more than 60 types of ITS investments. Information on IDAS is available at http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/trafficanalysistools/idas.htm.

Documentation and tools are available to support analysis of benefits and costs to support ITS project sequencing. The USDOT JPO has an ITS Benefits Database and Unit Cost Database website that can be found at http://www.benefitcost.its.dot.gov/. In addition to the databases, the website contains several documents highlighting ITS benefits. A tool developed by USDOT is the Intelligent Transportation System Deployment Analysis System (IDAS), a sketch-planning software analysis tool for estimating the benefits and costs of more than 60 types of ITS investments. Information on IDAS is available at http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/trafficanalysistools/idas.htm.

Identify Project Dependencies

With each ITS project defined in terms of the regional ITS architecture, the relationships between projects can be more easily identified:

In addition to the dependencies identified in the regional ITS architecture, ITS projects are also dependent on many other factors including the data or policy decisions that support the projects. For example, transit applications may be held up by the development of a bus stop inventory. A regional traveler information system may be held up by the lack of a regional base map. A regional fare system may be held up by a lack of consensus on regional fare policies. These types of dependencies should also be recognized and factored into the project sequence.

Define Project Sequence

A project sequence defines the order in which ITS projects should be implemented. A good sequence is based on a combination of transportation planning factors that are used to prioritize projects (e.g., identify early winners) and the project dependencies that show how successive ITS projects can build on one another.

Sometimes, many other factors influence the actual sequence of projects, so that developing an absolute rank ordering of projects is impractical during development or update of a regional ITS architecture. For example, the final decision about which projects will be funded may be made by the policy board of an MPO, which will not consider these decisions until after the regional ITS architecture is complete. In these cases, it may be reasonable to simply allocate projects to a rough timeframe such as short, medium, and long term. These allocations should still be based on the project evaluations and project dependencies. In three regional ITS architectures recently developed in New Jersey, this allocation was made to three timeframes: short term defined as "less than 5 years", medium term ("5-10 years"), and long term ("greater than 10-years").

In most cases, the first projects in the project sequence will already be programmed and will simply be extracted from existing transportation plans. Successive projects will then be added to the sequence based on the services and other components of the architecture and other planning factors.

As a sequence of projects is developed, also consider opportunities for including ITS projects in traditional transportation construction and maintenance projects that are planned for the region. Frequently, ITS elements can be efficiently included in traditional transportation projects; these potential efficiencies should be considered and reflected in the ITS project sequencing. For example, dependencies between the traditional transportation project and the ITS projects can be identified and the sequence can be aligned so that the ITS project is deployed at the same time as the associated construction and maintenance project. While efficiencies can be realized by synchronizing ITS projects with traditional transportation projects, it may be desirable to keep the capital improvements and ITS improvements contractually distinct so that separate funding can be used and/or that the lower cost, but possibly higher risk, ITS improvements can be more closely monitored and managed.

As a sequence of projects is developed, also consider opportunities for including ITS projects in traditional transportation construction and maintenance projects that are planned for the region. Frequently, ITS elements can be efficiently included in traditional transportation projects; these potential efficiencies should be considered and reflected in the ITS project sequencing. For example, dependencies between the traditional transportation project and the ITS projects can be identified and the sequence can be aligned so that the ITS project is deployed at the same time as the associated construction and maintenance project. While efficiencies can be realized by synchronizing ITS projects with traditional transportation projects, it may be desirable to keep the capital improvements and ITS improvements contractually distinct so that separate funding can be used and/or that the lower cost, but possibly higher risk, ITS improvements can be more closely monitored and managed.

The sequencing of projects in a regional architecture is similar to the development of an ITS Deployment Plan (a.k.a. Strategic Plan, Master Plan, etc.) that were developed prior to the development of regional architectures. When a regional architecture is developed, some regions incorporate the details of such plans within the architectures as the project sequencing while other regions prefer to maintain separate documents for the architecture and deployment plans. In the later case, the deployment plan should be referenced in the regional architecture so that it is clear that there is a connection between the projects contained in the plan and the architecture.

When a regional ITS architecture is being updated, note projects that have been implemented since the regional ITS architecture was developed or last updated. These projects should be updated (e.g., update project status to "Existing" or "Completed") and removed from the project sequencing. Completed project definitions may be retained within the regional ITS architecture as a record of implemented projects, depending on the needs of the region.

The real objective in defining a project sequence is to use the sequence as an aid in developing a more efficient sequence of projects in the transportation planning process. The project sequence documentation must be coordinated with the transportation planners and factored into the various transportation plans for the region for it to be of benefit. Additional information on use of the project sequencing output is presented in Section 7.

The National ITS Architecture "Market Packages" documentation on the Internet (http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/html/mp/mpindex.htm) and the Market Packages document (http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/html/menu/documents.htm) includes an extensive market package dependency analysis that identifies the important functional and information dependencies between market packages. This analysis may be a useful reference when performing the similar project dependency analysis discussed in this section. A discussion of "Early Winner" market packages is also included in the referenced document. In this discussion, market packages are evaluated for technical and institutional feasibility, general costs and benefits, and several other criteria that may be consulted as projects are sequenced based on similar factors.

The National ITS Architecture "Market Packages" documentation on the Internet (http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/html/mp/mpindex.htm) and the Market Packages document (http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/html/menu/documents.htm) includes an extensive market package dependency analysis that identifies the important functional and information dependencies between market packages. This analysis may be a useful reference when performing the similar project dependency analysis discussed in this section. A discussion of "Early Winner" market packages is also included in the referenced document. In this discussion, market packages are evaluated for technical and institutional feasibility, general costs and benefits, and several other criteria that may be consulted as projects are sequenced based on similar factors.

For more information on coordinating ITS projects with traditional transportation projects, see "Guidance on Including ITS Elements in Transportation Projects" from FHWA's Office of Travel Management (EDL document #13467, http://ntl.bts.gov/lib/jpodocs/repts_te/13467.pdf)

For more information on coordinating ITS projects with traditional transportation projects, see "Guidance on Including ITS Elements in Transportation Projects" from FHWA's Office of Travel Management (EDL document #13467, http://ntl.bts.gov/lib/jpodocs/repts_te/13467.pdf)

Turbo Architecture simplifies the task of relating regional ITS architectures and ITS projects. Turbo assists the operator by maintaining the detailed relationships between the region and supporting projects. It includes a report that identifies differences between the regional ITS architecture and related projects, and tools that automate the migration of changes between regional and project ITS architectures. Projects can be assigned an arbitrary "timeframe" and a structured status of up to seven user defined values that can be used to prepare a project sequencing report. An example of the Turbo Architecture project sequencing report for a few projects in the Georgia Statewide Architecture is shown in Figure 22

Turbo Architecture simplifies the task of relating regional ITS architectures and ITS projects. Turbo assists the operator by maintaining the detailed relationships between the region and supporting projects. It includes a report that identifies differences between the regional ITS architecture and related projects, and tools that automate the migration of changes between regional and project ITS architectures. Projects can be assigned an arbitrary "timeframe" and a structured status of up to seven user defined values that can be used to prepare a project sequencing report. An example of the Turbo Architecture project sequencing report for a few projects in the Georgia Statewide Architecture is shown in Figure 22

Figure 22: Georgia Statewide Architecture Project Sequencing Report

Identification of Project Sequencing Dependencies

It is beneficial to document the ITS project dependencies that influence the project sequencing. This analysis identifies the information and functional dependencies between projects based on the regional ITS architecture and any other external dependencies that affect the project sequence. Each project should list all other projects that it is dependent on and describe the nature of the dependency. The dependency description could be a narrative description, a categorization (e.g., functional or information dependency), or both.

Identification of Project Sequencing based on Local Priorities

Building on the project dependencies, this output defines an actual sequence of projects (or allocation of projects to timeframes) by factoring in local priorities, financial constraints, special requirements and objectives (e.g. modal shift priorities) that will influence the actual sequencing of projects. As discussed before, the project sequence can be documented in a variety of forms ranging from a simple listing of projects categorized as short, medium, and long-term through PERT charts that provide a detailed accounting of all project dependencies with a timescale overlay that indicates when projects will be implemented.

These two examples illustrate first, the analysis that can be done and summarized for projects to support assigning priority to the projects or allocating them to a timeframe, and second, the association of ITS projects to the regional ITS architecture.

Example 1: Eugene-Springfield ITS Plan Proposed Projects

Table 8, extracted from the "Regional ITS Operations & Implementation Plan for The Eugene-Springfield Metropolitan Area (November 2003)" documentation, provides a table of ITS projects. This example illustrates the analysis done on projects to allocate them to a priority or timeframe. Each project in this example includes a brief description, which in some cases decomposes the project to subprojects with different but related scopes. Each project (or subproject) is assigned a priority (which corresponds to allocating the project to a timeframe). Projects are cross-referenced to the local MPO TIP (the Central Lane MPO) where the project is already programmed. Project dependencies are identified, as well as estimates of capital and operations/maintenance cost, expected benefits and technical/institutional feasibility issues.

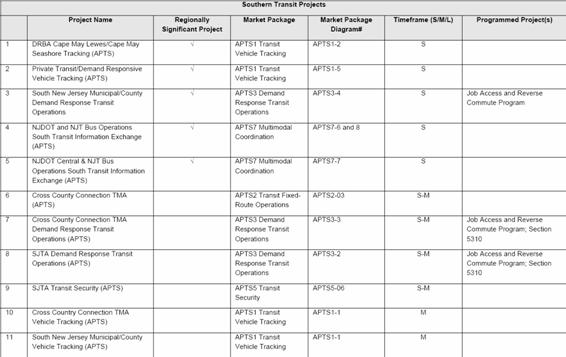

Example 2: South Jersey Transportation Planning Organization (MPO) Project Sequencing:

Table 9, extracted from the South Jersey Transportation Planning Organization (SJTPO MPO) regional ITS architecture, identifies transit ITS projects for the region and allocates them to short, medium, and long-range implementation horizons. This example illustrates how ITS projects are tied to the regional ITS architecture ITS elements, functions and information flows. Each project is associated with one or more market package instances from the regional ITS architecture, which are specifically identified in the table. These market package instances identify the specific ITS elements in the project as well as the information flows for those ITS elements. Figure 23 shows the market package instance identified for Project 3 in Table 9.

One issue with the market package instance in Figure 23 is that it's unlikely that all of the identified capabilities and information sharing that is shown will actually be implemented with a single ITS paratransit project. While a program is currently in place to fund this project for the county and municipal transit agencies in the region (described briefly in Table 9), these distinct agencies may access those funds on their own individual schedules according to their own capital plans. Also, as the traffic management agencies identified in the market package instance build or update their TOCs, they will be able to supply the "road network conditions" information flow to the transit management subsystems (and many other centers) that are ready (or become ready) to receive this information. In summary, it is important to understand that a market package instance may not be implemented all at once, but rather it is a guide to agencies that implement the associated service over multiple projects so that as the service is deployed, it is deployed in a regionally consistent way.

One issue with the market package instance in Figure 23 is that it's unlikely that all of the identified capabilities and information sharing that is shown will actually be implemented with a single ITS paratransit project. While a program is currently in place to fund this project for the county and municipal transit agencies in the region (described briefly in Table 9), these distinct agencies may access those funds on their own individual schedules according to their own capital plans. Also, as the traffic management agencies identified in the market package instance build or update their TOCs, they will be able to supply the "road network conditions" information flow to the transit management subsystems (and many other centers) that are ready (or become ready) to receive this information. In summary, it is important to understand that a market package instance may not be implemented all at once, but rather it is a guide to agencies that implement the associated service over multiple projects so that as the service is deployed, it is deployed in a regionally consistent way.

Example 3: Chittenden County Recommended ITS Projects:

Table 10 extracted from the Chittenden County Regional ITS Architecture developed by the Chittenden County Metropolitan Planning Organization, sequences ITS projects for the county over the short, medium and long term. Each project is defined in detail on project description tables as shown in Table 11. The projects are defined at varying levels of detail. The shorter term projects are defined in greater detail including specific locations (e.g. U.S. Route 7 — Shelburne Road Smart Corridor). Recognizing that the projects will be deployed over time, the projects are broken into phases which were scheduled and for which cost, benefits, etc. were better estimated.

Table 8: Eugene-Springfield ITS Plan Proposed Projects (excerpts)

Table 9: SJTPO (MPO) Project Definition and Sequencing (excerpt)

Figure 23: Market Package Instance for Project 3

Table 10: Chittenden County MPO Recommended ITS Projects

Table 11: Chittenden County MPO ITS Project Description

| Project Title | U.S. Route 7-Shelburne Road Smart Corridor |

|---|---|

| CCMPO Project Number | ITS-001 |

| Project Objectives | Provide traveler information to increase user-friendliness |

| Mitigate construction-phase traffic impacts | |

| Collect traffic planning and operations data | |

| Monitor operation of median U-turn lanes | |

| Expedite movement of emergency vehicles (Phase II) | |

| Improve long-term traffic management (Phase II) | |

| ITS Functional Areas | Advanced Traffic Management Systems |

| Advanced Traveler Information Systems | |

| Emergency Management Systems | |

| ITS Planning and Data Archiving | |

| Geographic Extents | U.S. Route 7 corridor, Towns of Shelburne and South Burlington. Subsequent phases might include key traffic signals in the southern portion of the City of Burlington. |

| Estimated Cost | Phase I: $207k + $25k O+M/year |

| Phase II: $653k + $65k O+M/year | |

| Anticipated Benefits | Mitigation of construction congestion |

| Improved construction management | |

| Real-time traveler information | |

| Improvement in travel time reliability | |

| More effective incident detection and management | |

| Reduced travel times and vehicle emissions | |

| Increased modal split to commuter rail | |

| Emergency vehicle prioritization | |

| Enhanced planning data collection | |

| Lead Agency | VTrans |

| Other Key Participants | Towns of Shelburne |

| City of South Burlington | |

| City of Burlington | |

| Emergency Service Providers | |

| CCTA (bus transit) | |

| Vermont Transportation Authority (rail) | |

| Deployment Considerations | Significant interagency/interproject coordination |

| Implications of VT privacy laws for CCTV cameras | |

| Deployment and Phasing Options | Phase I: Construction Phase Traffic Management |

| Phase II: Permanent ITS Infrastructure/ | |

| Corridor Signal Coordination | |

| Phase III: Integration with Regional ITS Systems | |

| Funding Opportunities | Shelburne Road Reconstruction Funds |

| CMAQ | |

| Prioritization | Early Success Opportunity |

| Phase I and II: Short-Term (Within 5 years) | |

| Phase III: Long-Term (5+ years) |

| These tasks may be performed in parallel |

|

|---|---|

| OBJECTIVES |

|

|

PROCESS Key Activities |

Prepare

|

|

INPUT Sources of Information |

|

|

OUTPUT Results of Process |

|

Agreements among the different stakeholder agencies and organizations are required to realize the integration shown in the regional ITS architecture. In this step, a list of the required agreements is compiled and new agreements that must be created are identified, augmenting agreements that are already in place.

Any agreements (existing or new) required for operations, including at a minimum those affecting ITS project interoperability, utilization of ITS related standards, and the operation of the projects identified in the regional ITS architecture are required in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)4 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.4.

Any agreements (existing or new) required for operations, including at a minimum those affecting ITS project interoperability, utilization of ITS related standards, and the operation of the projects identified in the regional ITS architecture are required in FHWA Rule 940.9(d)4 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.4.

Each connection between elements in the regional ITS architecture represents cooperation between stakeholders and a potential requirement for an agreement. Of course, this doesn't mean that hundreds of connections in the architecture will require hundreds of new agreements. One agreement may accomplish what is necessary to support many (or possibly even all) of the interfaces identified in the architecture. The number of agreements and the level of formality and structure of each agreement will be determined by the agencies and organizations involved. In many cases, agreements will already exist that can be extended and used to support the cooperative implementation and operation of ITS elements in the region.

At this step, a list of required agreements is compiled. Note that all that is required at this point is a list of the agreements, not the agreements themselves. The detailed work, including the preparation and execution of the identified agreements will be performed to support ITS project implementation later in the process. Although the agreements are not actually developed at this point, a fairly detailed understanding of the existing agreements in the region and the various options for structuring new agreements are critical to composing a realistic list of agreements.

Start by gathering existing stakeholder agreements that support sharing of information, funding, or specific ITS projects. Review each agreement and determine whether the existing agreement can be amended or modified to include additional new requirements for cooperation identified in the regional ITS Architecture. Decide if current agreements are sufficient until more specific operational agreements are identified in the future. If not, perhaps a handshake agreement or a simple Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) will suffice in the interim.

Armed with the operational concept, knowledge of the types of ITS elements scheduled for deployment (based on the TIP and the Project Sequencing from the regional ITS Architecture) and the information that needs to be exchanged, stakeholders should coordinate with other stakeholders with whom they are planning to exchange information and reach consensus on the agreements that will be required. Compile a list of the required agreements and prioritize those agreements that support near-term implementations.

The owners or operators of the elements that will be integrated should determine the types of agreements that are needed. Most organizations have a legal department or contracts division that already has approved operational agreements, funding agreements, etc. When possible, try to use an approved process to reduce the time needed to develop, review, and execute agreements.

In an emerging trend in ITS project implementation, many public agencies are working together with private companies (e.g., Information Service Providers and the media) to deliver services to the public. Responding to this trend, agreements needed for implementation of ITS projects aren't limited to agreements between public agencies. In many regions, agreements make public sector CCTV camera images available to the private sector for media use in traffic reporting. In other regions, agreements allow private sector CCTV camera images to be made available to the public sector for incident detection and surveillance, saving the public sector the cost of the cameras and their maintenance. These cameras may be located on public right-of-way, which also requires agreements for use of right-of-way.

In an emerging trend in ITS project implementation, many public agencies are working together with private companies (e.g., Information Service Providers and the media) to deliver services to the public. Responding to this trend, agreements needed for implementation of ITS projects aren't limited to agreements between public agencies. In many regions, agreements make public sector CCTV camera images available to the private sector for media use in traffic reporting. In other regions, agreements allow private sector CCTV camera images to be made available to the public sector for incident detection and surveillance, saving the public sector the cost of the cameras and their maintenance. These cameras may be located on public right-of-way, which also requires agreements for use of right-of-way.

There is considerable variation between regions and among stakeholders regarding the types of agreements that are created to support ITS integration. Some common types of agreements are shown in Table 12.

Avoid being "technology prescriptive" in the initial agreements whenever possible since technology changes rapidly. The technology selected during the planning phase may well change as the project nears the final design phases. Being too specific regarding technology can require numerous changes to any agreement throughout the life of the project. Of course, there are times when technology is non-negotiable — the region may have an agreement to use a specific standard or a legacy system must continue to be supported or the region has already made significant investments in a particular technology. In such cases, the agreements should reflect the technology decisions that have been made by the stakeholders of the region.

Avoid being "technology prescriptive" in the initial agreements whenever possible since technology changes rapidly. The technology selected during the planning phase may well change as the project nears the final design phases. Being too specific regarding technology can require numerous changes to any agreement throughout the life of the project. Of course, there are times when technology is non-negotiable — the region may have an agreement to use a specific standard or a legacy system must continue to be supported or the region has already made significant investments in a particular technology. In such cases, the agreements should reflect the technology decisions that have been made by the stakeholders of the region.

Table 12: Types of Agreements

| Type of Agreement | Description |

|---|---|

| Handshake Agreement. |

|

| Memorandum of Understanding. |

|

| Interagency Agreement |

|

| Intergovernmental Agreement. |

|

| Operational Agreement |

|

| Funding Agreement |

|

| Master Agreements. |

|

Rather than a focus on technology in early cooperative agreements, the focus should be on the scope-of-service and specific agency responsibilities for various components of the service. Describe the high-level information that each agency needs to exchange in order to meet the goals and expectations of the other rather than defining how the delivery of that information will occur.

The process may begin with something as simple as a handshake agreement. But, once interconnections and integration of systems begin, agencies may want to have something more substantial in place. A documented agreement will aid agencies in planning their operational costs, understanding their respective roles and responsibilities, and build trust for future projects. Formal agreements are necessary where funding or financial arrangements are defined or participation in large regionally significant projects is required.

The process of building consensus for a project agreement can build on the process of developing the regional ITS architecture: achieving regional consensus on needs, services, roles and responsibilities, and the architectural requirements on ITS elements, their functional requirements, information flows and standards for encoding the information flows. Once these institutional and technical issues have been agreed to, the foundation for the institutional agreements is in place.

In addition to the architecture elements identified above that can go into an agreement, deployment issues need to be considered and agreed to as well. For example: Who builds? Who operates? Who maintains? How are costs and/or revenues shared? How will liability be allocated? These sometimes very hard problems are often the most time consuming elements of an agreement.

A key benefit of developing a regional architecture based on a consensus process is that the transportation goals and solutions are identified early, so that these sometimes more difficult issues can be approached as soon as possible.

Agreements can take a long time to execute. Many regions have reported that three years is the average amount of time to build consensus, develop the contract(s), gather signatures, and execute the agreement. Plan accordingly. Begin the agreement process early, even if it is just a Memorandum of Understanding, while a more robust agreement is being developed.

Agreements can take a long time to execute. Many regions have reported that three years is the average amount of time to build consensus, develop the contract(s), gather signatures, and execute the agreement. Plan accordingly. Begin the agreement process early, even if it is just a Memorandum of Understanding, while a more robust agreement is being developed.

Agreements are time sensitive. Gain consensus and a commitment to schedule before the Agreement is circulated. This is especially important when executive-level changes impact the agencies strategic direction. One administration may be supportive and committed to sign a regional agreement and the next may not understand or simply may have a different funding agenda. Educating new stakeholders to the regional integration of ITS project process can take valuable time that has a domino affect on other agencies with regard to executing an Agreement.

This output will be a list of required agreements, including both existing and planned agreements that need to be put into place. Each list entry identifies the agreement title, the stakeholders involved, the type of agreement that is anticipated, high level status (existing or planned), and a detailed and concise statement of the purpose of the agreement. Each entry should also reference the regional ITS architecture in some way. For example, identify the name of a project that is mapped to the regional ITS architecture for project level agreements, an interface or set of interfaces for a specific information exchange agreement, or possibly an ITS element in the inventory. The exact nature of the reference to the regional ITS architecture is highly dependent on the nature and scope of the agreement. If specific ITS standards are being considered for the interface, it's helpful to include this information as well. In many cases, a general commitment to "compatible interfaces" and use of a general standards family is sufficient for initial agreements.

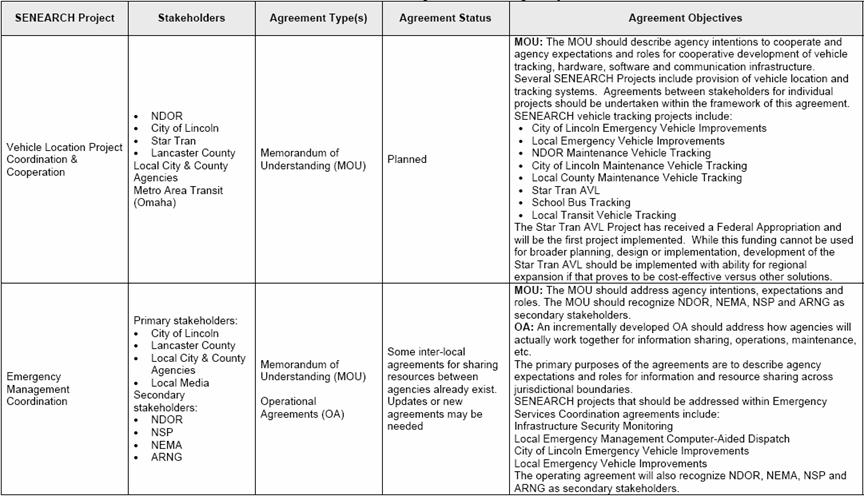

The following example, shown in Table 12, is a partial list of agreements taken from the Southeast Nebraska Regional ITS Architecture for the City of Lincoln. This regional ITS architecture identifies required agreements based on the projects developed for the region.

Table 13: Southeast Nebraska Regional ITS Architecture Agreements

TOC Previous Page Next Page