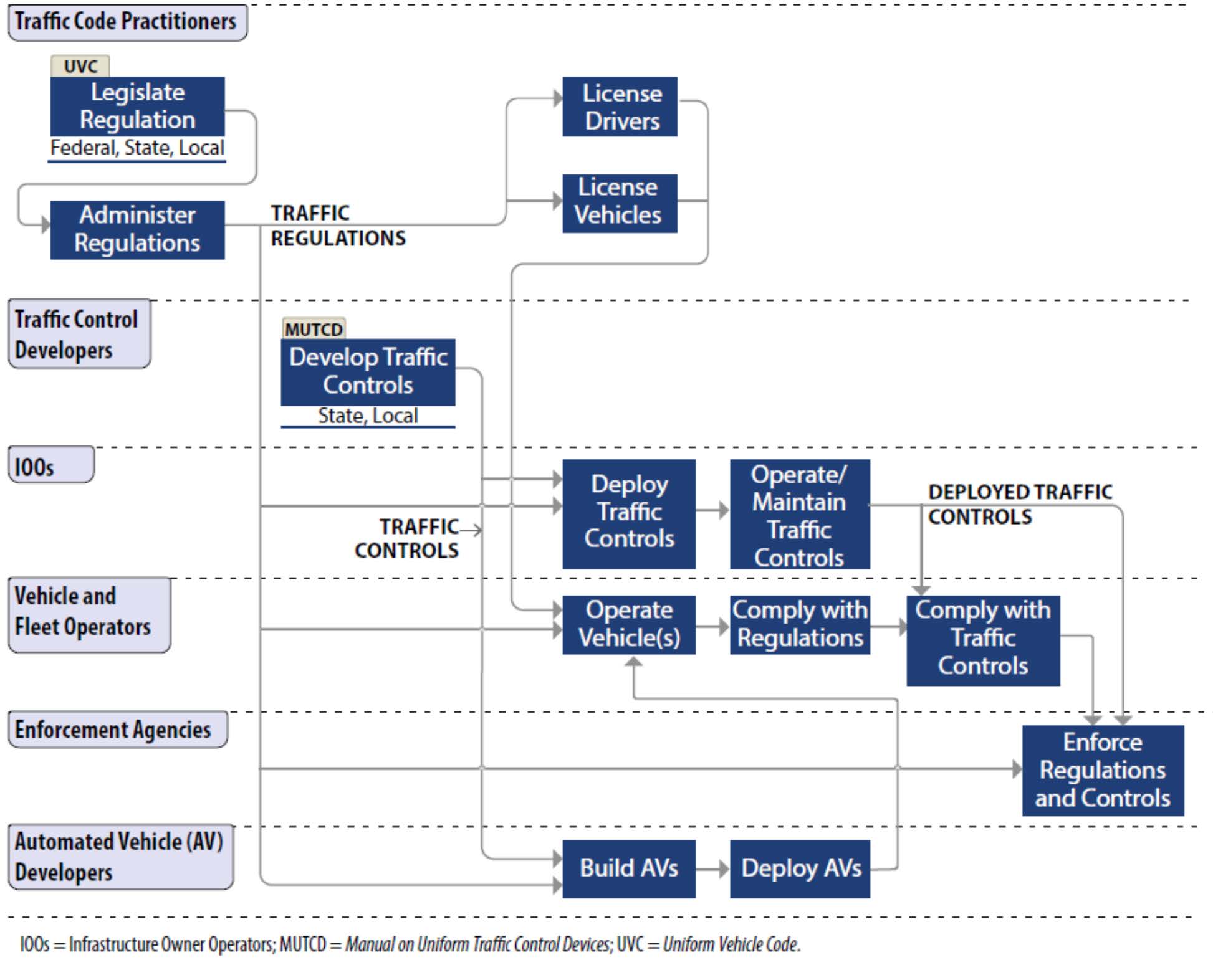

Chapter 3. Needs for Traffic Regulation Data in Automated Driving System DevelopmentThe Need for an Automated Driving System Regulations Data FrameworkDevelopers of automated driving systems (ADS) and associated technologies want and will eventually need their products to work seamlessly across the nation. The deployment of automated vehicles (AV) will of course not happen everywhere at the same time, and the evolution of AVs over time will achieve higher levels of automation across more operational design domains (ODD). In the meantime, AVs will occupy roadways with human-driven vehicles and be subject to the same traffic regulations and controls, or perhaps even more restrictive regulations designed to limit conflicts with human drivers and other road users. As seen in the prior discussion of existing traffic regulations, there is a significant diversity of traffic regulations, controls, custom, and enforcement across the nation. The essentials of the driving tasks and maneuvers are necessarily consistent, but the constraints on particular movements may vary. The basis for this variation has to do with the ways that traffic regulations are created, administered, applied in design, applied in practice, and enforced in different jurisdictions. Figure 4 depicts this process conceptually, in terms of traffic regulations, stakeholders, their actions on and use of regulations, and the flow of regulation information among activities.  Source: FHWA Figure 4. Diagram. Traffic regulation and automated vehicle interactions. Stakeholders in traffic regulations interact with those regulations in roles ranging from legislators and their assistants who draft and enact traffic laws to those who enforce and adjudicate the laws as they are applied to traffic events and circumstances on the roadways. These roles are listed on the left side of Figure 4:

The blue boxes in Figure 4 represent activities undertaken by the traffic regulation stakeholders to assure that vehicles and their drivers operate safely and effectively on the nation’s roadways. Traffic regulations are created and enacted at the Federal,31 State, and local government levels by legislators and their staff with input from transportation agencies, and to some extent, private commercial entities and the public. Once enacted, the regulations are administered by other State and local agencies, such as departments of transportation, departments of motor vehicles, driver license bureaus, and State highway patrol and police. These administrative groups will also license drivers and vehicles for those jurisdictions in which they will be operating. Development of traffic controls renders the intent of the legislated traffic regulations into forms that can be localized to the roadway for driver instructions and constraints on vehicle behavior. Each body of traffic regulations requires a set of traffic controls to be developed and applied within its jurisdiction. Once the traffic control devices are defined, they need to be deployed to the roadways as applicable to the particular context for which the control is designed. Dynamic traffic controls such as traffic signal systems need to be configured and operated so as to manage local traffic flow and safety conditions. Both static and dynamic controls need to be maintained such that they are visible and actionable by drivers and vehicles. Licensed drivers are legally enabled to operate licensed vehicles on the roadways. These operations are to be in compliance with both traffic regulations—the body of traffic law applicable within the jurisdiction(s) in which the vehicle is operated—and the local traffic controls. This is an important distinction, in that the regulations are in practice implicit to those operations and may not be locally marked or signed. Regulations of this type might include rules such as speed limits on particular roadway classifications where not otherwise posted, right turns being permissible on a steady red signal, or “move over laws” when law enforcement and emergency workers are present. Vehicle operations are generally also subject to local custom where actions are based on standards of reasonableness or implicit negotiation between vehicle operators. Law enforcement operates both explicitly on the roadways and in the legal systems. Enforcement may be by State and local police and patrols, or by automated means in some jurisdictions. The application of traffic laws may need adjudication in the legal system when the laws depend on standards of reasonableness or operator judgement. The forms of traffic regulations as they exist in the current world of human-driven vehicles, and as they will need to persist into a world of ADS and AVs, are represented in the Figure 4 diagram by ellipses. The Uniform Vehicle Code (UVC) provides a set of traffic regulation on which State and local traffic codes may be based. It represents a historical consensus on traffic regulation, but has no legal standing and is not normative for regulations. “Traffic regulations” are the rules of the road as detailed in the State and local statutes that describe the legal objectives and obligations, the operational requirements, and the consequences of violations. The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) is a common national standard for markings and signage on roadways. It both comes from and is used as a reference for development and application of controls by State and local agencies. The MUTCD is published by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) but has legal standing only insofar as adopted by the State and local agencies. “Traffic controls” represent the types of regulatory markings and signs on the roadways that may be needed to assure safety and preserve mobility in traffic movement. In this context, they represent the types of traffic controls based on the MUTCD with State and local variations. “Deployed traffic controls” are markings and signs of various types as they are deployed on the roadways in particular locations for particular modes of operation at particular times. User Perspectives and NeedsEach stakeholder group involved in the development and application of traffic regulations brings a different perspective to the needs for a regulations data framework. Individuals from across those groups were interviewed to solicit and clarify their perspectives on the process, nature of regulations data, and potential interactions with the framework. Key concepts and needs identified in those interviews are captured in this section. Many of the interviews provided insightful observations ending in questions as to how the issues might unfold with ADS development and deployment. Traffic Code PractitionersTraffic code practitioners prepare, enact, and administer traffic regulations. They work with IOOs to implement those regulations and deploy traffic controls, and with enforcement agencies to ensure drivers comply with those regulations. Traffic code practitioners identified few specific needs, but did imply caution in the interpretation and application of existing regulations to ADS. Their observations include the following: "There is no testing a law. You just have to write the law and see what happens." – Traffic code practitioner in interview Language matters. Existing regulations may refer to the operator of a vehicle as a “person,” “driver,” or “operator,” but those terms need to be evaluated in context to determine if they apply to ADS. It will be necessary to identify specific actors and actions to infer application. Standards for “reasonableness” are spread throughout traffic law, alongside inexact but commonly understood language expressing the need for “caution.” These ambiguous phrasings will need interpretation to become applicable to ADS. It is sometimes acceptable in practice to not obey traffic laws—for example, in moving past an incident. These behaviors are generally determined by collective action or by local direction from law enforcement and emergency services. It is unclear how that would be arranged for ADS. Legal cases and review are part of building the body of law. Case law does not always result in changes to the enacted legislation. It is unclear how interpretations in case law would be captured for a regulations framework. Traffic laws can sometimes be ambiguous and lack a standard of reasonableness that circumvents translation to a digital format. Behaviors in these situations have unknown implications for AVs. Human drivers use custom and negotiation to navigate these circumstances, but ADS may default to behaviors that conservatively interpret regulations and violate local customs. Human drivers may use hand gestures and facial expressions to negotiate movements with other drivers. How will those interactions be facilitated among AVs and human drivers, or simply among AVs? Traffic Control DevelopersTraffic control developers specify standards for traffic control indications—pavement markings and signage—on the roadways. This specification occurs at a national scale in the development of the MUTCD as facilitated by FHWA, but becomes part of the body of State traffic regulations by reference within the statutes to the particular State traffic control codes. This is a critical and largely uncontroversial part of implementing the rules of the road, but the manner in which it develops has implications for a regulations data framework. Comments in interviews included the following: The MUTCD is updated relatively infrequently—about every 10 years—and in arrears of traffic devices having already been installed in some locations. The innovations are collected by consensus from State and local traffic control deployment experience for standardization and publication. Controls for work zone scenarios are the fastest growing section of the MUTCD. Optional guidance is provided in the MUTCD to allow flexibility for design and local custom. This variability may factor into State and local preferences for particular implementations, which are then encoded in traffic laws for those States and localities. These preferences then become the basis for and cause of traffic control diversity across the country. As a result, it will be necessary to go to every State (and potentially local agency) to identify controls specific to those jurisdictions. Infrastructure Owner-OperatorsIOOs include State and local agencies deploying, operating, and maintaining traffic controls in fulfillment of the guiding statutes. Most State traffic codes authorize these agencies to codify traffic controls appropriate to their respective States (in their roles as traffic control developers), rather than specify the traffic controls within the statutes. The IOOs are responsible for deploying those controls on the roadways, operating the dynamic controls such as traffic signals and ramp meters, and maintaining the controls. IOOs in these capacities support enforcement agencies in ensuring that drivers comply with the regulations. Observations from the interviews included the following: The unstated presumption on traffic control deployments appeared to be that pavement markings and signs would need to continue to be deployed indefinitely for human drivers and ADS. It was acknowledged that some changes in deployment and maintenance might need to be made to accommodate ADS sensing and perception subsystems—for example, restriping roadways with 6-inch stripes and maintaining an acceptable level of reflectivity. There was concern that trying to maintain a digital representation of deployed traffic control devices would quickly become untenable. Sign databases are not always well maintained by State or local agencies, and the number of traffic signs is higher than generally appreciated. It was also noted that deployment of traffic controls can create conflicts between jurisdictions over control and standards. Such situations can arise, for example, on State routes through municipalities where varying traffic control device preferences or standards are being deployed. Such issues with jurisdictional control may be referred to courts for adjudication. Vehicle and Fleet OperatorsVehicle operators are the key stakeholders in ensuring compliance with traffic regulations as vehicles move throughout the roadway network. This responsibility falls to individual drivers and, to a lesser extent, dispatchers and managers of fleets of vehicles. Human drivers will continue to have this responsibility even with development and deployment of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) through automation Level 3, and for ODDs not explicitly automated at Level 4. ADS on vehicles operating at automation Levels 4 and 5 will fully subsume this responsibility for their designated ODDs. Perspectives on and needs for the regulations data framework from the ADS itself are discussed under the ADS developers section below. Enforcement AgenciesIn the context of the regulations framework, enforcement agencies include those that monitor roadways for violations and those that adjudicate perceived violations in the traffic courts. Roadway traffic law enforcement is generally performed by municipal police forces, sheriff departments, and State police or highway patrol. Some locations have enacted automated enforcement means such as red-light cameras and speed sensors, some of which provide only warnings, and some of which issue citations for violations. The traffic court systems become involved when drivers question citations, whether by officers or automated means. Interviewees noted that the enforcement of traffic laws with AVs and all levels of driving automation is a subject of intense interest among agencies. The American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA) has issued some initial guidance on the subject and continues to be in conversation with ADS developers. Current topics of interest include, for example, whether AVs should provide an indication external to the vehicle that it is being operated by an ADS. This type of indication would help enforcement officers in knowing how to approach a vehicle in violation of a traffic rule. Key considerations for the purposes of the regulations framework are that enforcement actions and traffic case law may need to be included in the framework when enforcement agencies accumulate experience with AVs and potential violations. Automated Driving System DevelopersADS developers are any of those researchers and programmers working on behalf of academic institutions, governmental agencies, technology companies, and vehicle manufacturers involved in ADS development. There is a tremendous diversity of interest in and approaches to ADS development within this community. The sample of interviews conducted for this study ranged from start-up tech companies to large multinationals, and from tier-one suppliers to light- and heavy-vehicle manufacturers. All interviewees were clear about their need for reliable, consistent regulatory data in support of ADS development. ADS developers consistently expressed concerns about the diversity of regulations among jurisdictions, especially with regard to the letter of the law, and the need for a precise understanding of its intent for each jurisdiction.This leads to potential conflict for ADS behavior. The developers would prefer a harmonized understanding of traffic regulations across jurisdictions to enable the development of consistent behavioral algorithms. This was usually expressed during interviews in descriptions of specific ODD challenges and the impact of regulation diversity on those instances—for example, in passing regulations and keeping right; letting others pass; four-way, stop-sign-controlled intersections; or entering an intersection on a yellow traffic signal. The consistent expression of concern about diversity and complexity of regulations may be a significant limitation on the ODDs for which automation is developed, at least in the near term. ODDs do not necessarily line up with the manner in which the regulations were enacted. The regulations were set up for human drivers based on situations they would encounter along the roadways. ODDs have thus far been identified and described by individual ADS development teams based on their business plans and needs. There does not appear to be any particular regard for standard or systematic ways of ensuring that all regulations, use cases, and development needs would eventually be addressed. One interviewee suggested that traffic laws can be considered part of the ODDs themselves, implying a level of complexity in ODDs similar to that in the regulations. As such, ODDs may be limited in the near term to those with the fewest or least complex regulations, or at least those with the most specific rules. Another common thread of discussion was around questions of how regulations depending on a human vehicle operator might apply to ADS-equipped vehicles. This seemed to be a greater concern for ADS-equipped heavy vehicles—for example, with laws about putting reflective triangles out behind disabled vehicles. Interviewees expressed mixed perspectives on whether regulations information should reside onboard the vehicle, presumably encoded as algorithms, or be made available from a data cloud over a vehicle-to-vehicle (V2I) connection. Some envisioned a regulations service similar to a map service, but all observed that vehicles will need to be able to operate without connections, at least for some period of time, especially in rural areas. There seemed to be distinct perspectives on development for light vehicles and for heavy vehicles. This may be due in part to the Federal regulations on heavy-vehicle operations (related in turn to regulation of interstate commerce). There may need to be an assessment of the interfaces between traffic regulations and permitting for heavy vehicles that will affect routing and operations across or around their ODDs. One interviewee summarized ADS developer concerns with traffic regulations as being a significant part of their greater concern with a need for standardization and guidance on testing and certification of ADS behavior for the intended ODDs. 31 For example, “Vehicles and Traffic Safety,” Code of Federal Regulations (annual edition). Title 36: Parks, Forests, and Public Property. Part 4: VEHICLES AND TRAFFIC SAFETY, Monday, July 1, 2019. [ Return to note 31. ] |

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||