Chapter 7. Equity and Public PerceptionEquity relates to how user costs and other outcomes will impact people in different income brackets and of different races/ethnicities, gender, English proficiency level, and travel mode. This chapter explores the cross-cutting findings of the STSFA Phase Ⅰ sites with regard to equity considerations of a potential future RUC system. Key Cross-Cutting FindingsAs discussed in chapter 6, questions regarding the equity and “fairness” of an RUC resonate with diverse stakeholders and community members. However, a key challenge that States implementing pilots encounter is that different interest groups define “fairness” differently. Project sites identified multi-pronged approaches to address equity:

EQUITY CONCERNS RELATED TO ALTERNATIVE TRANSPORTATION FUNDING MECHANISMS CALL FOR A STRUCTURED APPROACH INVOLVING:

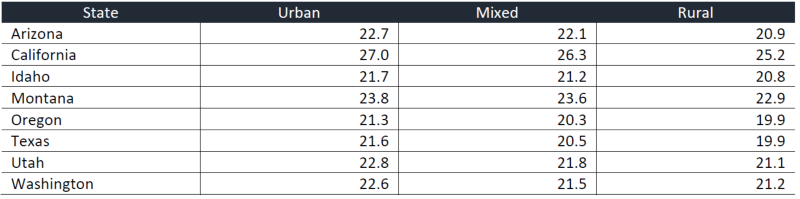

Agencies need to be mindful that, even after taking the proposed steps above, some interest groups may continue to view RUC as inherently inequitable, particularly with regard to some of the common concerns discussed in this chapter. The common equity concerns raised by project sites regarding RUC and the approaches to address or mitigate the same are detailed below. This narrative significantly draws upon the Eastern Transportation Coalition (ETC) Technical Memorandum, Equity and Fairness Considerations in a Mileage-Based User Fee System,13 and RUC West and Oregon’s Financial Impacts of Road User Charges on Urban and Rural Household14 study conducted as part of Phase Ⅰ. Fairness by Distance DrivenThe Eastern Transportation Coalition memorandum highlights the concern that some stakeholders have shared assuming that a mileage based fee would penalize longer commutes. The Coalition contends that the concept that a user pays based on usage is the intent of RUC. The memo explains that ”Just like one pays for telephone or electricity service in proportion to usage—the greater your use of electricity, the higher your electricity bill—a transportation tax should be usage based.” However, one of the key recommendations of ODOT’s Focus Group Report, was to avoid comparing RUC to other things people pay for based on usage such as electricity, water, cell phone minutes, cable channels, etc., because focus group participants perceived driving vehicles to be a necessity and not easily controlled. Instead, the ODOT report recommends the emphasis of “the uniqueness of driving as a resource” and the importance of adequate transportation funding to ensure the roads are maintained and enhanced. The Eastern Transportation Coalition Technical Memorandum further elaborates how longer commute distances correlate with lower incomes. The memorandum cites the Brookings Institute 2015 study that indicated that trends between 2000 and 2012 show a shift in minority residents towards the suburbs, thus negatively impacting job proximity. This trend was particularly pronounced among residents of high-poverty and majority-minority neighborhoods. However, the study also notes that these trends were not uniform across the country. In regions where this observation is true, it may be likely that RUC is, or is viewed as, a regressive form of tax. However, this is not largely different from a fuel tax, which also places an undue burden on residents that travel longer distance for work. The following approach may provide a roadmap to addressing some of these real or perceived equity concerns. Identification, analyses, and quantification of problem. While the Brookings Institute 2015 study provides national trends on job proximity of low-income residents, these results may or may not be directly applicable to every State or region.15 Identification of potentially affected groups and analyses of RUC impacts on them would help to determine the exact nature and extent of any problem, such as what the incremental tax burden is likely to be for specific income categories for a proposed RUC rate structure versus the existing fuel tax.16 Most critically, evaluating the incremental tax burden in itself would illuminate the magnitude of the RUC burden versus the fuel tax burden for individual drivers. Developing approaches to address or mitigate inequities. Longer driving distances equate to a higher fuel tax burden as well. State- or region-specific analyses could also consider the types and fuel efficiency of vehicles currently owned by target groups (i.e., low-income drivers) and the impact that has on their current tax burden. As fuel tax is a more accurate proxy of transportation system usage for gas-powered vehicles, it is likely that the tax burden of low income groups is lower or remains largely unchanged under an RUC program as compared to the current fuel tax structure based on type of vehicles owned. Fairness by Rural Versus Urban LocationAnother recurring criticism of RUC has been the potential for inequitable burden on rural versus urban drivers, given that the former, by reasons of geography and land use, drive longer distances on average. Identification, analyses, and quantification of problem. The most significant effort undertaken as part of STSFA Phase Ⅰ was the study conducted by RUC West on the financial impacts of RUC on households. This report analyzes the financial impacts of a revenue-neutral RUC for drivers in urban and rural counties for eight States in the RUC West Consortium—Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Texas, Utah, and Washington.17 The analysis conducted for this study was applied uniformly to all eight participating States so that a clearer and more comprehensive assessment of the impact of RUCs could be developed, and so that any differences in financial impact on a State-by-State basis could be understood. Fuel type mixtures and efficiencies were estimated with the vehicle registration data provided by the States (Figure 2), which indicates consistency in fuel efficiency for urban, mixed, and rural locations across all eight States, with urban areas having the highest average fuel efficiency, decreasing across mixed areas, with the lowest value in rural areas.  Source: RUC West

Figure 2. Average fuel efficiency (miles per gallon) for vehicles in urban, mixed, and rural census tracts of project States (gas-taxed vehicles only).

To better understand the financial impact a revenue-neutral RUC would have on urban, mixed, and rural households, the report looked at driving patterns. Using 2009 National Household Travel Survey data, the study found little difference between urban and rural households nationally in terms of trip frequencies. However, the National Household Travel Survey showed much longer trip lengths for rural households, including nearly twice as much travel for shopping trips. A key finding of the study was that, while rural drivers tend to drive slightly more miles per day than urban residents, they are generally driving older and less fuel‐efficient vehicles than their urban counterparts. Assuming that an RUC program will credit any paid fuel taxes back to the motorist, most rural drivers may see a positive impact from participating in an RUC program. In fact, the RUC West-sponsored prior report on this issue indicates, on average, rural households will pay between 1.9 and 6.3 percent less, while urban households will pay 0.3 to 1.4 percent more, State tax in an RUC system than they currently pay in State gas tax.18 Ranges reflect the differences from State to State (see Table 13).

Source: Modified from RUC West by the Eastern Corridor Coalition.

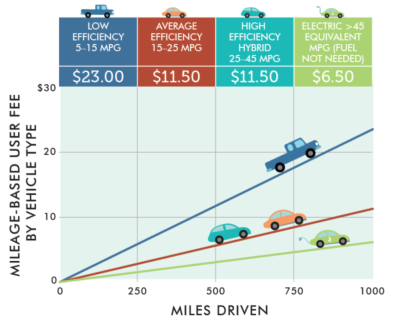

Communication and messaging. As previously noted, the argument of unfairness can also be applied to the current gas tax—more miles driven equates to more gas purchased and more gas tax paid. Moreover, rural drivers tend to drive less fuel-efficient vehicles and, therefore, pay more for each mile driven. Fairness by Fuel Efficiency and Vehicle TypeThe central argument in favor of an RUC is the inherent “fairness” of a system where all drivers pay their fair share of transportation expenditures, as determined by how much they drive. Despite that fact, a persistent counter-argument that several sites have encountered in their outreach is that an RUC is unfair to drivers of electric/hybrid vehicles, which are more environmentally friendly than gas-powered vehicles. These constituents believe that people who purchase cleaner vehicles should be rewarded for this socially desirable choice with lower charges. Identification, analyses, and quantification of problem. The Eastern Corridor Coalition Technical Memorandum proposes the following for RUC rate structuring to address the issue of equity in this context: From a financial and transportation revenues perspective, consideration might be given to the concept of a variable MBUF rate structure that charges a higher per-mile rate for vehicles with lower fuel efficiencies such that these vehicles pay no less than they currently pay in gas tax (ignoring the possibility that many of these vehicles may be owned by low-income and/or rural residents). A lower rate would be charged for those vehicles with fuel efficiencies at about the average MPG—in essence, a “revenue-neutral” rate. In this manner, there would be no reduction in transportation revenues from these vehicles relative to what is currently collected from the gas tax. Highly fuel efficient and electric vehicles would still be charged MBUF—thereby slightly increasing revenues—but at the lowest per-mile rate, recognizing their “contribution” to the environment. Figure 3 shows a comparison of a mileage-based charge and the current gas tax paid by vehicle time and miles driven developed by the Eastern Transportation Coalition.

Source: Eastern Corridor Coalition Figure 3. Graph. Hypothetical average mileage-based user fee paid by vehicles with different fuel efficiencies.

Communication and messaging. The Eastern Corridor Coalition Technical Memorandum lays out several arguments to counter the perceived unfairness of RUC to fuel-efficient vehicles, as summarized below:

Significant Phase Ⅰ Efforts Exploring Equity and Public AcceptanceThis section presents significant Phase Ⅰ findings with regard to the equity implications of alternative transportation funding solutions, in addition to the RUC West study cited above. Road Usage Charge West’s Study of Equity ConcernsThe RUC West explores the following chief concerns with equity related to RUC, regardless of specific State programs:

The RUC West ConOps also draws from the prior experiences of member States and the Coalition to highlight the results of studies related to equity impacts, particularly the following conclusions:

Oregon’s Focus GroupsOregon conducted a series of focus groups in September 2017 to map the path to acceptance of RUC by identifying specific points of concern and specific points of comfort. One group consisted of people driving electric or hybrid vehicles, and these participants were especially likely to think that drivers of fuel-efficient vehicles should pay less than drivers of less-efficient vehicles: Survey results indicated that the increased cost per month for those with fuel efficient vehicles was seen by many as a disincentive to get such vehicles. This was especially the case in the electric/high MPG hybrid focus group, who had no problem paying for road use. They made it clear that it was not the additional amount they would pay (which was seen as insignificant), but rather the principle of a disincentive for those who made the choice to “do the right thing” by purchasing an environmentally-friendly vehicle. Other questions regarding RUCs posed by members of the focus group made up of electric and hybrid vehicle drivers included the following:

Further, over the course of the focus group, despite the participants being introduced to several persuasive messages about RUC (“persuasive” as graded by the participants themselves), the support for RUC among the electric and hybrid vehicle focus group decreased. Eastern Corridor Coalition’s Pre- and Post-Pilot SurveysThe Eastern Corridor Coalition surveyed participants at the beginning and the end of the pilot. The Coalition noted that, the largest change in opinions on the fairness of a MBUF was related to very fuel-efficient vehicles: The number of pilot participants who believed MBUF [mileage-based user fee] was “less fair” for very fuel-efficient cars increased from 27% at the beginning of the pilot to 38%; while the number of participants who said MBUF was “more fair” for fuel-efficient vehicles went down from 39% at the beginning of the pilot to 24% following the pilot.21 13 I-95 Corridor Coalition. 2019. Equity and Fairness Considerations in a Mileage-Based User Fee System. n.p. [ Return to Return to Note 13. ] 14 RUC West and Oregon Department of Transportation. Financial Impacts of Road User Charges on Urban and Rural Households. Available at: https://www.ebp-us.com/sites/default/files/project/uploads/FINAL-REPORT---Financial-Impacts-of-RUC-on-Urban-and-Rural-Households_Corrected.pdf. [ Return to Return to Note 14. ] 15 Kneebone, E. and N. Holmes. “The Growing Distance Between People and Jobs in Metropolitan America.” Brookings Institute. April 1, 2016, n.p. [ Return to Return to Note 15. ] 16 Congressional Budget Office. 2011. “Alternative Approaches to Funding Highways.” March 23, 2011. [ Return to Return to Note 16. ] 17 RUC West and Oregon Department of Transportation. Financial Impacts of Road User Charges on Urban and Rural Households. Available at: https://www.ebp-us.com/sites/default/files/project/uploads/FINAL-REPORT---Financial-Impacts-of-RUC-on-Urban-and-Rural-Households_Corrected.pdf. [ Return to Return to Note 17. ] 18 Ibid. [ Return to Return to Note 18. ] 19 Union of Concerned Scientists. 2015. Cleaner Cars from Cradle to Grave – How Electric Cars Beat Gasoline Cars on Lifetime Global Warming Emissions. Available at: https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/cleaner-cars-cradle-grave. [ Return to Return to Note 19. ] 20 Tessum, Christopher W., Hill, Jason D., and Marshall, Julian D. 2015. “Life Cycle Air Quality Impacts of Conventional and Alternative Light-Duty Transportation in the United States;” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2014/12/10/1406853111. [ Return to Return to Note 20. ] 21 I-95 Corridor Coalition. 2019. Equity and Fairness Considerations in a Mileage-Based User Fee System. n.p. [ Return to Return to Note 21. ] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||