MODULE 7: Driver Safety Issues

LESSON 1: DISTRACTIONS

Distracted driving, a form of driver impairment as dangerous as drinking and driving and drowsy driving, is a deadly epidemic on America's roadways. In 2013, there were 3,154 people killed in distracted driving crashes. This represents a 6.7 percent decrease in the number of fatalities recorded in 2012. About 424,000 people were injured—an increase from the 421,000 people who were injured in 2012.139 An estimated 80 percent of collisions involve some form of driver inattention, and each year, driver inattention is a factor in more than 1 million crashes in North America, according to American Automobile Association (AAA).140 These figures most certainly underestimate the role of distraction in fatal crashes because data is self-reported and, "It is rare that cell phone billing records are subpoenaed and examined."141 This is not the case, however, when crashes involving oversize load movement occur.

Since 2009, the U.S. Department of Transportation has held national distracted driving summits, has banned texting and cell phone use for commercial drivers [49 CFR §392.82], encouraged States to adopt tough laws, and launched several campaigns to raise public awareness about the dangers of distracted driving.

Engaging in visual-manual activities (such as reaching for a phone, dialing, and texting) associated with the use of hand-held phones and other portable devices increased the risk of getting into a crash by three times for light vehicles and cars.142 However, for heavy vehicles or trucks, dialing a cell phone increased the risk of a crash or near-crash event to 5.9 times as high as non-distracted drivers.143 Studies also show that 5 seconds is the average time a driver's eyes are off the road while texting. When traveling at 55 mph, that's enough time to cover the length of a football field blindfolded.144 Looking away from the path of travel for 2 or more seconds doubles the likelihood of a crash, according to AAA.145

Headset cell phone use is not substantially safer than hand-held use.146

The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) suggests that completely mitigating cognitive distraction is unlikely, in part because it is more difficult to identify and measure than activities that take a driver's eyes off the road or hands off the wheel.147

Drivers are approximately 400 percent more likely to crash when talking on cell phone while driving.148 However, according to the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, "With 75 percent of drivers believing hands-free technology is safe," drivers are often surprised to learn these new vehicle features may actually increase distraction. Voice-activated interactions were most distracting when they were less accurate. Studies found that drivers miss stop signs, pedestrians (who are often also looking at a screen), and other cars while using voice technologies.149

Whenever a driver's attention is not on the road, that driver is putting himself/ herself and passengers, other vehicles and their occupants, and pedestrians in danger.150 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describes three main types of distractions while driving: visual distractions, which cause you to take your eyes off the road; physical distractions, which cause you to take your hands off the wheel; and mental distractions, which cause drivers to take their mind off the task of driving.151 Distractions include (but are not limited to) talking to passengers; adjusting the radio or media player, climate controls, and mirrors; eating, drinking, or smoking; reading maps or other printed material; picking up something that fell; reading billboards; watching other motorists or their passengers; and of course, talking on cell phones and the ultra-dangerous behavior of texting or checking email while driving.

According to a study performed by the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute, text messaging creates a crash risk 23 times (that's 2300 percent) worse than driving while not distracted.152

Sending or receiving a text takes a driver's eyes from the road for an average of 4.6 seconds. That means when traveling at 55 mph and looking at a text, the driver is operating the vehicle blindly for the distance of an entire football field. Texting is so much more dangerous than talking because texting, as well as dialing, scanning contacts, and checking email, involve all three types of distractions simultaneously: hands off the wheel, eyes off the road, and mind off the task. Driving tasks are on "pause" during the time a driver is interacting with a device (or engaged in other distractions), often for 4 or 5 seconds at a time, and often while the vehicle is moving more than 100 feet per second (approximately 70 mph).

Distractions are deadly because of the lack of driver vigilance and slower reaction times, among other contributing factors. If drivers react a half-second slower because of a distraction, crashes double.153

Here are some ways to avoid becoming distracted while driving:

- Review and be familiar with all safety features of the vehicle being driven; the driver should be totally familiar with all in-vehicle electronics before driving.

- Clear the vehicle of any unnecessary objects.

- Review maps and plan the route before driving.

- Adjust all mirrors, seat, and steering wheel before driving.

- Do not attempt to read or write while driving.

- Avoid smoking, eating, and drinking while driving.

- Do not use cell phones or any other electronic devices while driving. When drivers need to make phone calls, they should find a safe place to park to make telephone calls.

- Never use the cell phone for social conversations while driving.

P/EVOs must not only refrain from distractions, they must watch out for distracted drivers. Safe drivers learn to recognize other drivers engaged in distracting behaviors. Vehicles that drive over the lane divider lines or weave within their own lane, or who drive over the fog line may be distracted.

Given the risks associated with using cell phones and similar devices while driving, combined with the relative ease with which phone records can be obtained, the risks associated with cell phone use not only represent a physical danger to the distracted driver and all highway users, they represent a liability issue that P/EVOs (and all drivers) must consider. Distracted drivers not only risk their own lives and the lives of their passengers and nearby motorists, they also risk substantial financial losses.

It is clear that distractions are dangerous, but the solution is not complex. When a professional driver is found to be at fault, the costs to the driver who chooses to take such risks are not limited to death, personal injury, and property damage. It is often the case that the driver's license will be suspended, ending the driver's ability to work as a P/EVO, at least for some period of time. Even when the driver's license is re-instated, carriers are highly reluctant to hire a driver with an at-fault crash on his or her driving record. In addition, insurance companies also refuse to cover risky drivers, or demand very high premiums that for many P/EVOs are simply out of reach.

Distractions are deadly. All drivers, especially professional ones, must recognize this danger and avoid becoming another casualty. The P/EVO's job requires vigilance beyond that of other highway users. For this reason, in addition to the other reasons provided here, the escort vehicle should be a No-Phone Zone.

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

- What are the three types of distractions?

- Are hands free devices safe to use while driving? Are they substantially different than handheld devices?

- What is meant by the statement, "Driving is multitasking?"

- How can drivers avoid becoming distracted?

- How much more likely are talking drivers to crash, when compared to non-talking drivers? How much more likely are texting drivers to crash?

- Why is texting (or dialing a phone or scanning contacts or checking email, anything that involves interacting with a screen) so much more dangerous than talking on a cell phone?

LESSON 2: DROWSY DRIVING (FATIGUE)

According to the IIHS Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI), driver fatigue is an increasing factor in crashes. Truck drivers working for more than 8 hours are twice as likely to crash.154 When a driver is sleepy, trying to "push on" is far more dangerous than drivers think. Drowsy driving is a major cause of fatal accidents.

According to the CDC, among nearly 150,000 adults studied, aged at least 18 years or older in 19 States and the District of Columbia, 4.2 percent reported they had fallen asleep while driving at least once in the previous 30 days! Individuals who snore or sleep 6 hours or less each day were more likely to report this behavior, and drivers who get 7 to 9 hours of sleep each day are involved in less than half as many crashes whether they snore or not.155

The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) estimates that more than 100,000 crashes annually are the direct result of drowsy driving, resulting in an estimated 1,550 deaths, 71,000 injuries, and $125 billion in monetary losses.156 The CDC states these estimates are probably conservative, though, and up to 5,000 to 6,000 fatal crashes each year may be caused by drowsy drivers.157

Hours of Service Rules

As was the case when the 2004 Pilot Car Escort Training Manual: Best Practices for Pilot Car Escorts was published, P/EVOs are not required to follow hours of service (HOS) rules or maintain logbooks (unless the escort vehicle is 10,000 pounds or is otherwise subject to commercial vehicle rules). Commercial carrier regulations do not apply to P/EVOs. This does not mean, however, that P/EVOs should schedule assignments that prevent adequate rest—7 to 9 hours of sleep per day, as the CDC suggests.

Surveys indicate that many commercial drivers violate the regulations, working longer than permitted.158While changes in HOS rules enacted in 2012 are an improvement over 2003 rules, these new rules "might still allow more driving than the regulation before 2003," according to the IIHS.159 The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) has produced an hours of service visor card that explains the rules for holders of commercial driver's licenses (CDL).160

Dangers of Drowsy Driving/Fatigue

Crashes involving sleepy drivers have several characteristics: these crashes occur late night/early morning or mid-afternoon; crashes are likely to be serious and involve a single vehicle leaving the roadway; crashes occur frequently on high- speed roads when the driver is alone and does not attempt to avoid a crash.161

According to CDC,162 the specific driving skills that are negatively affected by fatigue include:

- Attention to detail.

- Reaction times.

- Ability to think and act decisively.

Other major findings about the impact of fatigue on drivers include:

- Driver alertness and performance are more consistently related to time-of- day than to time-on-task.

- During their daily main sleep period, drivers slept for only about 5 hours, at least 2 hours less sleep than the ideal requirement of 7 to 9 hours.

- Drivers' self-assessments of levels of alertness did not correlate well with objective measures of performance. In other words, drivers are not very good at assessing their own levels of alertness.163

Recognizing Danger Signs of Drowsiness and Fatigue

All drivers, regardless of rules and regulations related to HOS, must plan for adequate rest just as carefully as they plan other parts of load movement operations. Drivers must learn to recognize the early signs of fatigue. When drivers are unable to respond to events quickly, regardless of the reason, they are compromising safety.

Every driver must understand his or her body's natural clock, and the natural patterns of alertness and rest. The studies cited above show the time of the trip is as important as the consecutive hours of driving. If a P/EVO typically sleeps between midnight to 6:00 a.m., for example, then performing escort duties during that normal rest period increases the risk of fatigue.

As mentioned, another time period during which the risk of fatigue is elevated is after lunch. For many people, the two hours after lunch is the most difficult time to stay awake. Even when team members get enough rest overnight, it is important for P/EVOs to monitor themselves and each other during times when alertness is compromised.

Sleep is not voluntary. After about 17 hours of being awake, people become drowsy and the body begins to experience "micro-sleeps," brief lapses that can last for several seconds. At 50 miles an hour, during a 4-second lapse, the vehicle moves 300 feet. If any of the following happen, it is time for the driver to rest:

- The driver has difficulty focusing or his or her eyes close.

- The vehicle repeatedly hits the rumble strips delineating the shoulder.

- The driver has trouble keeping his or her head up.

- The driver can't stop yawning.

- The driver has wandering, disconnected thoughts.

- The driver doesn't remember driving the last few miles.

- The driver is tailgating or missing traffic signs.

- The driver keeps jerking the vehicle back into the lane or drifting across lanes.

- The driver misses a turn or exit.

- The driver has difficulty remembering exit numbers, addresses, or street names.

Perhaps of most importance, though, is that P/EVOs must have the courage to speak up and stop driving when fatigue is present. Drivers too frequently continue driving when fatigued, and the consequences are very similar to those that involve drinking drivers.164

These more recent findings are consistent with previous studies. For example, the National Transportation Safety Board concluded that the critical factors in predicting crashes related to fatigue were:

- Duration of the most recent sleep period.

- The amount of sleep in the previous 24 hours.

- Fragmented sleep patterns.165

According to the NHTSA,166 the critical aspects of driving impairment for fatigued drivers are: negative effects on reaction time, vigilance, attention, and information processing abilities.

As mentioned above, numerous studies have shown that drowsy drivers perform no better on driving tasks than drinking drivers.167 And in addition, low levels of alcohol (below the legal limit of .08% for drivers; .04% for CDL holders) amplify the effects of inadequate sleep.168

Drowsy drivers may feel morally superior to the drinking driver, or feel that fatigue is not as dangerous as drinking and driving, but tests show fatigued drivers are no better at driving than those who have been drinking alcohol.Fatigue and Vision

Early signs of fatigue related to vision include being bothered by oncoming headlights (a sign that pupil constriction is slowed, increasing glare blindness), having difficulty keeping eyes open and focused, being troubled by burning and/or watering eyes, and failing to maintain a visual lead and manage space around the vehicle.169

Fatigue means the body is shutting down. For adults, there is no solid line between being asleep and being awake. Rather, falling asleep is a process. And one of the first things the body does as it transitions from wakeful alertness to sleep is it stops processing visual information—obviously a concern for every driver.

Drivers should have a comprehensive eye examination at least once a year, and an extra pair of glasses should be within reach of all drivers who require them.170 Drivers who use contact lenses often have adverse effects on vision after 10 to 12 hours of wearing contact lenses. Drivers should have glasses, as well as sunglasses, available, even if the driver typically wears contact lenses.

Preventing Drowsy Driving

Get enough sleep. Driving for long periods of time is tiring. Even the best drivers become less alert. It is important for drivers to get enough sleep. Sleep cannot be "saved up" and many workers in all fields in the United States operate with a sleep deficit. The average adult needs 7 to 8 hours of sleep during every 24-hour period, according to the National Institutes of Health.171

Seek treatment for sleep disorders. Sleep disorders are significant for drivers and should be monitored and corrected.

Arrange work schedules to avoid starting a trip with a "sleep deficit," and try to schedule trips for the hours drivers are typically awake. Many heavy vehicle crashes happen between midnight and 6 a.m. Tired drivers fall asleep during these times, especially if they don't regularly drive during those hours. Trying to push on and finish a long trip at these times can be very dangerous.172

Avoid drinking alcohol before driving. Follow all State laws in terms of hours prior to driving that must be alcohol free. And, remember that rules for CDL holders are more strict than those for other drivers.

Avoid medication that produces drowsiness. Pay attention to warnings on medication labels, especially those that warn against operating vehicles or machinery. One of the most common examples is over-the-counter cold medication. A driver is better off suffering from the cold symptoms than from the drowsy-inducing effects of medication that reduces those symptoms.

Exercise regularly. This builds resistance to fatigue and improves the quality of sleep. Eating healthy food is also beneficial. While it is frequently difficult for drivers to find healthy food, they should look for ways to incorporate balanced meals and snacks. As nearly every health organization stresses, consume more fruits and vegetables and less fat, salt, and sugar. Use caffeine sparingly.

Keep the vehicle cool. Hot, poorly ventilated vehicles can produce sleepiness. Open a window or vent and use the air conditioner to keep the environment cool.

Take breaks that involve physical activity. Inspect the vehicle and/or take a short, brisk walk. It is especially important to take a mid-afternoon break when all people, including drivers, typically experience drowsiness.

In summary, when a driver becomes sleepy, stop to sleep. Take a nap. Do NOT rely on coffee or another source of caffeine. Do NOT rely on an open window, sour candy, singing to the radio, using a cell phone, or other "tricks" that often add to the danger. When a driver is sleepy, there is one solution: sleep.

In the future, electronic on-board recorders (EOBR) may become required equipment. The IIHS has petitioned Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) for a mandate many times (1986, 1987, 1995, 2005), arguing EOBRs "will make regulation more effective and reduce truck driver fatigue," according to the IIHS.

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

- How does getting 7 to 9 hours of sleep each day affect a driver's chance of being involved in a crash?

- How does fatigue (also called "drowsy driving") affect driving skills?

- How does time of day affect driver alertness?

- What are "micro-sleeps?"

- How do fatigued drivers and drinking drivers compare in terms of driving skill?

- What should drivers do to avoid fatigue?

LESSON 3: AGGRESSION

NHTSA defines aggressive driving as an event that occurs "when individuals commit a combination of moving traffic offenses so as to endanger other persons or property." Some other communities define aggressive driving as "the operation of a motor vehicle involving three or more moving violations as part of a single continuous sequence of driving acts, which is likely to endanger any person or property."

Road rage differs from aggressive driving. Road rage is a criminal offense, defined as "an assault with a motor vehicle or other dangerous weapon by the operator or passenger(s) of one motor vehicle on the operator or passenger(s) of another motor vehicle or is caused by an incident that occurred on a roadway."

The American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AMVA) defines aggressive driving as the act of operating a vehicle in a selfish, bold, or pushy manner, without regard for the rights or safety of others, and road rage as operating a vehicle with the intent of doing harm to others or physically assaulting a driver or his or her vehicle.

Behaviors typically associated with aggressive driving include: exceeding the posted speed limit, following too closely/tailgating, erratic or unsafe lane changes, improperly signaling or failing to signal lane changes, and failure to obey traffic control devices (stop signs, yield signs, traffic signals, railroad grade cross signals, etc.). NHTSA labels running a red light as one of the most dangerous forms of aggressive driving.173

A dangerous form of passive/aggressive behavior is obstructing traffic, in particular, driving at or under the speed limit in the left lane. Most States have rules indicating the left lane is for passing only; when drivers ignore that law, they create moving roadblocks that further frustrate drivers.

High traffic volume, tight schedules, and unexpected delays such as encountering an oversize load, produce a rich environment for aggressive driving and road rage. Americans drive more miles every year, and many drivers take out their anger and frustration on other roadway users.

Somewhat ironically, many aggressive drivers were in a negative frame of mind before they ever entered their vehicles, but aggressive individuals most often blame others for difficulties they encounter.

What Can a Pilot/Escort Vehicle Operator Do To Minimize Aggressive Behavior?

P/EVOs can reduce frustration in several ways. First, it is important that the team be realistic about travel times.

When drivers leave too late to arrive at the destination on time, trying to make up the time while driving is a dangerous, albeit popular, strategy. P/EVOs must acknowledge this and resist any temptation to participate in such behaviors. If an individual is angered by other drivers and stressful traffic conditions, a career as a P/EVO is not recommended.

One way to minimize stress is to avoid being distracted by a clock. Recognize that ideal traffic conditions are not typical. Drivers must accept that if they depart late, they will arrive late. It is important from a safety standpoint to acknowledge the reason for a late arrival was a late departure rather than something other drivers may have done.

Expect delays and be courteous to other drivers. Slow down and maintain adequate following distance. Do not drive in the left lane unless passing other vehicles; as mentioned, to do so creates moving roadblocks that frustrate drivers and create or elevate unsafe conditions.

Avoid gestures, even those not intended to provoke another driver. Keep your hands on the wheel and your eyes on the road and surrounding vehicles.

Avoid cutting people off — this is much easier when drivers are not distracted. Be responsive to other drivers— accommodate their needs to change lanes or merge onto a roadway.

What Can a Pilot/Escort Vehicle Operator Do If Confronted by an Aggressive Driver?

If the team encounters an aggressive driver, make every attempt to get out of the way. Do not challenge an aggressive driver or attempt to restrict their movement. Avoid eye contact and ignore any gestures.

Report aggressive drivers to the appropriate authorities by providing a vehicle description, license number if possible (do not tailgate in order to read the tag number, however), and the vehicle's location and direction of travel. If an aggressive driver is involved in a crash, stop a safe distance from the crash scene, wait for the police to arrive, and report what you witnessed.174

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

- What are the differences between aggressive driving and road rage?

- What are some of the behaviors exhibited by aggressive drivers?

- What can P/EVOs do if confronted by an aggressive driver or witnesses an incident of road rage?

LESSON 4: GENERAL SAFE DRIVING PRACTICES175

As with other safety issues, knowing the oversize load maneuvering limitations is crucial to safe load movement. Safe drivers are always monitoring surroundings for hazards. By learning to see hazards and maintaining focus on the roadway and traffic, hazards are substantially less likely to become emergencies. By watching for hazards and maintaining a safe distance from other vehicles, drivers have time to plan a way to avoid an emergency and execute the plan successfully. When a P/EVO sees a hazard, that driver must continually consider emergencies that can develop with the particular load being escorted, and decide how to reduce the risks involved. Driving at night, in fog, in very hot weather, and in mountains present extra challenges when moving oversize loads, as discussed in the next sections.

Adverse or hazardous conditions include anything that negatively affects visibility, traction, or braking. Conversely, good conditions means flat, level, dry pavement in the daytime. When incidents happen, rarely is some previously unknown hazard found to have contributed to it. Rather, we as drivers make the same kinds of mistakes under similar conditions, as explained below.

Driving in Adverse Conditions

Nighttime Driving

Nighttime driving presents greater risks primarily because of drivers' inability to see hazards as quickly as in daylight, and therefore, they have less time to respond. Problems related to driving at night involve the driver, the roadway, and the vehicle. Driver factors include vision, glare, and fatigue. People don't see as sharply at night or in dim light. Also, drivers' eyes need time to adjust to dim light and varying light as when driving through tunnels. Glare can blind drivers for short periods, and eyes take some time to recover from this temporary blindness. This is similar to the effect of a camera flash. It can take several seconds to recover from glare, and alcohol and medications can negatively affect how quickly pupils constrict, extending the problem. Even two seconds of "glare blindness" can be dangerous.176 As looking away from the road for two seconds doubles crash risk, glare blindness can produce similar risks. Remember, a passenger vehicle moving at 50 mph moves 75 feet per second; at 70 mph, that is 105 feet per second. And remember the increased distances required for large vehicles to stop. In the time it takes for a driver's vision to recover, the vehicle will have moved about half the distance of a football field. If a vehicle approaching you has high beam headlights on, or the lights are particularly bright, look at the right side of the road, at the fog line.

Roadway factors affecting drivers at night include poor lighting and inadequate highway markings. Another hazard of nighttime driving is the increased prevalence of drinking drivers and fatigued drivers. Finally, the vehicle factor that negatively affects driving at night the most is the limitation of headlights. Drivers must be sure they can stop in the distance they can see ahead. With low beams, drivers can see ahead about 250 feet; high beams vary from 350 to 500 feet. Drivers must adjust speed to keep stopping distance within sight distance. If a driver is not able to stop within the range of the headlights, by the time the driver sees a hazard, he or she cannot stop before striking it.

Dirty headlights not only cut down the driver's ability to see, they also reduce the visibility of the vehicle. Headlights can be out of adjustment, i.e., not pointed in the right direction. In addition to reducing the ability of the driver to see, the lights may create problems for other drivers if pointed at them. It is particularly important at night for drivers to ensure all lights are working and clean, including brake lights, tail lights, turn signals, and warning lights.

It is important for P/EVOs to check lights on the load vehicle as well as other escort vehicles, and notify drivers if lights are not working properly. It is also important for P/EVOs and load drivers to carry replacement bulbs for all lights on the vehicle. Clean windshields and mirrors are particularly important for nighttime driving. Bright lights at night can cause dirt on the windshield or mirrors to create glare. If using high beams, in the absence of nearby traffic, dim lights within 500 feet of oncoming vehicles or vehicles in front. Headlights from behind, shining into cars moving in the same direction create glare from reflections in mirrors. So, dim headlights when moving within 500 feet of a vehicle ahead. As mentioned, look at the side of the road, at the fog line if present, when meeting vehicles. Do not turn on high beams within 500 feet of an oncoming driver. This is dangerous as the glare can blind the driver and he or she may drift across the centerline. This behavior is aggressive and frequently provokes other drivers, including P/EVOs. Avoid these behaviors and minimize reactions to them.

At dawn or dusk, in rain or snow, it is more difficult for motorists to see the load. In order to be seen, all drivers should use low beam headlights at all times, day and night. This is especially beneficial when the vehicle is white, silver, gray, or blue—colors that blend into the horizon. Drivers should use high beams only when it produces no negative effect for oncoming drivers or drivers traveling in front of the load or P/EVO.

If the plan calls for a part of the trip to be made during nighttime hours, make sure you are rested and alert before the trip begins. If drowsy, sleep before driving. Even a nap can save lives. Make sure eyeglasses are clean and unscratched. Be sure to inspect the vehicle, especially lights, at every opportunity when traveling at night. Clean the inside and outside of the windshield and mirrors frequently.

Driving in Fog

Fog can occur at any time and on highways can be extremely dangerous. Fog is often unexpected and visibility can deteriorate rapidly. Watch for foggy conditions and be ready to reduce speed. Do not assume fog will thin out after entering it. Maintain stopping/sight distance. A best practice is to avoid driving in fog. Pull off the road into a rest area or truck stop until visibility improves. Parking on the shoulder in foggy conditions is not recommended.

If a driver cannot stop safely when encountering fog, be sure to obey all fog- related warning signs; slow down before entering fog; use low-beam headlights and fog lights, even in daytime; be alert for other drivers who may have forgotten to turn on their lights; turn on four-way flashers; watch for vehicles on the side of the roadway (seeing taillights or headlights in front of you in fog may not be a true indication of where the road is; the vehicle may not be on the road at all); use highway reflectors as guides to determine how the road may curve; listen for traffic you cannot see; avoid passing other vehicles.

Driving in Extreme Heat

Hot weather requires checking tire pressure every 2 hours or 100 miles in very hot weather. Do not let air out as the pressure will be too low when the tires cool. If a tire is too hot to touch, remain stopped until the tire cools off; the tire may blow out or catch fire otherwise. It is also important to monitor engine oil levels and temperature gauge. Make sure the engine cooling system has enough water and antifreeze based on the engine manufacturer's directions. (Antifreeze helps the engine under hot conditions, too.) Carefully monitor the water temperature gauge. Remember that if a coolant reservoir is available, and if it is not part of the pressurized system, coolant may be added even if the engine is at operating temperature. It is never safe to remove the radiator cap or any part of a pressurized system until it is cool. Steam and boiling water can spray, causing severe burns.

If the radiator cap is cool enough to touch with bare hands, the engine is probably cool enough to open. If coolant needs to be added and there is no reservoir, follow these steps:

- Shut engine off.

- Wait until engine has cooled.

- Protect hands (use gloves or thick cloth).

- Turn radiator cap slowly to the first stop, which releases the pressure seal.

- Step back while pressure is released from cooling system.

- When all the pressure has been released, press down on the cap and turn it further to remove it.

- Visually check level of coolant and add more, if necessary.

- Replace the cap and turn it all the way to the closed position.

Belts and hoses are also negatively affected by high temperatures. Learn how to check belt tightness by pressing on the belts. Loose belts will not turn the water pump and/or fan properly, resulting in overheating. Failure of coolant hoses can lead to engine failure and even fire.

While driving in extremely hot conditions, watch for bleeding tar that is very slippery. Also, remember that high speeds create more heat for tires and the engine.

Driving in Mountainous Terrain

Gravity plays a major role in mountain driving. On upgrades, gravity slows the vehicle. The steeper the grade, the longer the grade, and the heavier the load, the more the load driver must use lower gears to climb mountains. In coming down long, steep downgrades, gravity causes the speed of the vehicle to increase. Selecting a safe speed and maintaining proper distance from the load vehicle is vital for the lead P/EVO.

In selecting a safe following distance, it is important to consider the stopping distance of the load vehicle, specifically:

- Total weight of the vehicle and cargo.

- Length of the grade.

- Steepness of the grade.

- Road conditions.

- Weather conditions.

If a speed limit or a sign indicating maximum safe speed is posted, never exceed the speed shown. Shift to lower gears before starting down a grade. Avoid downshifting after speed is built up, for either manual or automatic transmissions.

Brakes are designed so that brake shoes or pads rub against the brake drum or disc to slow the vehicle. Braking creates heat, and brakes are designed to sustain heat. However, brakes can fade or fail from excessive heat caused by using them too much and not relying on the engine braking effect (i.e., using lower gears) — an essential element of safe mountain driving.

Brake fade is also affected by adjustment. In order to safely control a vehicle, every brake must do its share of the work. If one brake is not doing the work it is designed to do, this puts extra stress — and heat — on the remaining brakes. This can produce overheating and fading, leaving inadequate braking power to control the vehicle. And, brake linings wear faster when they are hot.

The use of brakes on a long or steep downgrade is only a supplement to the braking effect of the engine. Once the vehicle is in the proper low gear, do the following:

- Apply brakes just hard enough to feel a definite slowdown.

- When speed has been reduced to approximately 5 mph below the safe operating speed, release the brakes (this brake application should last for about 3 seconds).

- When speed has increased to a safe speed, repeat steps 1 and 2.

Escape ramps are available on many steep mountain downgrades and should be included on the route survey. These ramps are made to stop runaway vehicles safely without injuring drivers and passengers. P/EVOs should know the locations of escape ramps, and this is the kind of information that must be covered in the pre-trip meeting each day. This level of detail about the route is too much to remember for the entire trip, so remind team members — when the information becomes vital — in a daily briefing.

In mountainous terrain, the lead escort must be vigilant about the distance between the P/EVO and the load vehicle and be aware of brake issues. Adequate distance must be maintained in order to avoid the P/EVO being struck from behind by the load. For the rear P/EVO, when the load is moving uphill, it is recommended to allow enough distance to accommodate drivers approaching from the rear who may not detect how slowly the load is moving. By creating more distance between the rear P/EVO and the load, vigilant rear P/EVOS will have room to tap brakes to get attention of drivers approaching too quickly from the rear, as well as speeding up themselves to avoid being struck from behind. Needless to say, this system provides an extra measure of safety to the load vehicle, as well. (See also Managing Speed and Space and Braking Tips sections below.)

Managing Speed and Space

Why Speed Matters

According to IIHS, as vehicle speed increases, stopping distances as well as crash severity also increase. A large truck traveling at 75 mph takes about one-third longer to stop than one traveling at 65 mph. Large trucks often weigh 15 to 40 times more than passenger cars; stopping distances substantially increase. This is particularly important for lead escorts to remember.

Petitions by American Trucking Associations, Road Safe America and individual carriers have asked the Federal government to require speed governors on large trucks weighing 26,000 pounds or more that would set maximum speed at 68 mph, and would be tamper resistant with penalties for tampering. These issues continue to be debated.

Driving too fast is a major cause of fatal crashes. Drivers must adjust speed depending on weather and light conditions, traffic volume, size of load, features of the terrain, type and condition of roadway surface, and other factors.177

Speed matters because of stopping distances.178 Stopping a vehicle involves first seeing an obstruction, then deciding what to do, actually moving foot from accelerator to the brake pedal, and judging the distance it takes the vehicle to stop based on its size and weight; speed; roadway surface (gravel or asphalt, wet or dry); and whether the vehicle is on a down slope, up slope, or is on level terrain; how well the brakes are functioning; the vigilance, experience, and skill of the driver, and other factors. When crashes occur, drivers may see the obstruction, and conditions may be favorable (i.e., dry, level pavement), but there is simply not enough distance to get the vehicle stopped before striking an obstruction, including other vehicles.

Perception distance refers to the distance a vehicle travels, in ideal conditions, from the time a driver sees a hazard until the brain recognizes it. The average perception time for an alert, non-distracted driver is 1.75 seconds. At 55 mph, the vehicle has traveled more than 140 feet in that 1.75 seconds (1 mph = 1.5 feet/sec). Fatigue is a critical factor in perception time for both the load driver and the P/EVO. The decision making process is slowed and seconds are often doubled as are the corresponding distances. So at 60 mph, the vehicle travels 88 feet per second. (Three quarters of a second = 66 feet.)

Reaction distance refers to the distance the vehicle will continue to travel, in ideal conditions, before the driver applies the brakes in response to the hazard. The average driver has a reaction time of 0.75 to 1 second. So, at 55 mph, the vehicle moves an additional (average) of more than 60 feet — the amount of time it takes the driver to apply the brakes AFTER the driver perceives the brakes are needed. The average reaction time is another 0.75 second, or another 66 feet, for a total of 132 feet before the vehicle begins to slow down.179

Braking distance refers to the distance the vehicle travels, in ideal conditions, while the driver is braking. At 55 mph on dry pavement with good brakes, a standard tractor-trailer rig (i.e., not oversize or overweight) takes about 216 feet to stop.

Stopping distance, then, is the sum of these three distances—perception distance + reaction distance + braking distance. Substantially more distance is needed for fatigued drivers, distracted driver, drivers on a down slope, or stopping on a wet roadway.

Braking Tips180

Brake in a straight line. Do one thing at a time. For example, when turning, brake before making the turn. When negotiating a curve, brake before entering the curve.

The Effect of Speed on Stopping Distance181

The faster a vehicle moves, the greater the impact or striking power of the vehicle. When speed doubles, from 20 to 40 mph, for example, the impact is 4 times greater. The braking distance is also four times longer. Triple the speed from 20 to 60 mph, and the impact and braking distance is nine times greater. At 60 mph, the stopping distance for a tractor-trailer is longer than a football field. Increase the speed to 80 mph and the impact and braking distance are 16 times greater than they were at 20 mph. High speeds greatly increase the severity of crashes and injuries.

Matching Speed to Road Conditions182

Slippery surfaces require longer distances to stop, and also make it harder to turn without skidding. Slippery surfaces include, as mentioned above, bleeding tar in extremely hot conditions, but more typically, slippery conditions are associated with rain and ice. Roads are slippery when rain begins, for example, and ice may be hard to detect in shady areas and on bridges and other elevated surfaces.

Speed should be adjusted to allow the vehicle to stop in the same distance as on a dry road. Reduce speed by about one-third (slow down from 60 to 40 mph, for example) on a wet road. On packed snow, reduce speed by half or more. If the surface is icy, reduce speed to a crawl and stop driving as soon as you can safely get off the roadway and out of the way of skidding vehicles.

Slippery surfaces are sometimes difficult to detect. Watch for shady areas; they will remain icy and slippery long after the open areas have melted. Bridges freeze before the road does. Be especially careful when the temperature is close to 32 degrees. Watch for melting ice (wet ice); it is much more slippery than ice that is not wet. Black ice is a thin layer that is clear enough that you can see the road underneath it. The road appears wet. So when the temperature is below freezing and the road looks wet, it may be black ice.

An easy way to check for ice is to open the window and feel the front of the mirror or the mirror support. If there is ice on these, the road surface is probably starting to ice too. With respect to rain, beware of slippery conditions just after rain begins. The rain mixes with oil left on the road by vehicles. As rain continues to fall, the oil is washed away.

Hydroplaning is like water skiing — the tires lose their contact with the road and have little or no traction. It is difficult to control the vehicle — steering and braking are compromised. To regain control, drivers should release the accelerator but avoid applying the brakes. It does not take a lot of water to cause hydroplaning, and hydroplaning can occur at speeds as low as 30 mph when there is a lot of standing water on the roadway. Hydroplaning is more likely if tire pressure is low or when the tread is worn. The grooves in a tire carry away the water; if they are shallow, they don't work well. Finally, road surfaces where water collects create conditions that increase hydroplaning possibility.

Speed and Curves

Drivers must adjust speed for curves in the road. Taking a curve too fast, two bad things can happen. First, the tires can lose traction and continue straight ahead, so the vehicle skids off the road. Or, the tires may keep their traction and the vehicle rolls over. A load vehicle with a high center of gravity can roll over at the posted speed limit for a curve. Lead P/EVOs must communicate any obstructions or problematic road surface conditions to the load driver in time for the driver to slow to a safe speed. This meets the responsibility for protecting motorists by working to ensure the load vehicle maintains traction, i.e., the ability to stop and steer.

Speed and Traffic Flow

Many local jurisdictions have restrictions about oversize loads moving in and around big cities during peak traffic volume. When driving in heavy traffic, the safest speed is the speed of other vehicles; vehicles moving in the same direction at the same speed are not likely to run into one another. However, oversize loads are an exception to this rule. First, avoid peak traffic times whenever possible, if the permit allows it at all. In many States, speed limits are lower for trucks, and may be even lower for oversize loads. A national speed limit for trucks of 65 mph has been proposed by many, while much research suggests collisions occur more frequently when large trucks travel slower than other traffic. Allowing adequate following distance and avoiding driving alongside large trucks appear to be most effective at reducing crashes, along with uniform traffic flow, and traveling at speeds appropriate for conditions.

Changing lanes becomes more difficult, as does maintaining a safe following distance, when transporting an oversize load. As traffic volume increases, vehicles travel much closer together. Beware of drivers who try to drive faster than the speed of traffic; these drivers take risks and increase the chances of a crash. Stay as far to the right as possible and maintain as much distance as possible around your vehicle.

Speed on Downgrades

Vehicle speed increases on downgrades because of gravity. The driver's most important objective is to select and maintain a speed that is not too fast for the total weight of the vehicle and load, the length of the grade, the steepness of the grade, road conditions (wet or dry, smooth or pot holes, etc.) and type (gravel, asphalt, etc.), and weather (including visibility and traction/braking issues).

Managing Space

Safe drivers maintain space all around their vehicles.183 When things go wrong, space gives drivers time to see, think, and act. In order to have space available when something goes wrong, drivers must manage space. This is true for all drivers, and it is very important when operating (or escorting) large vehicles that require much more space for stopping and turning.

Space ahead. Of all the space around a vehicle, it is the area ahead of the vehicle — the space it is moving into — that is most important. Space ahead is important in case the vehicle must be stopped suddenly. According to accident reports, the vehicle that trucks and buses most often run into is the one in front of them. The most frequent cause is following too closely. Crash possibilities increase substantially if inadequate space ahead is not maintained. Given the difference in weight, trucks hitting cars results in more fatalities. And, remember: if the vehicle ahead of you is smaller than yours, it can probably stop faster than you can.

How much space ahead? Experts suggest that in good conditions (i.e., flat, level, dry pavement in the daytime), following distance should be a minimum of three seconds, with drivers adding one second for each hazardous condition that may exist. For example, if it is raining, add one second. If it is raining (visibility hazard) and it has been raining all night (standing water hazard), add two seconds. If the driver only slept six hours the previous night, add another second for the delayed reaction and perception time produced when a driver is operating with a sleep deficit.

Following distances for large trucks must be greater than the three-second rule. For a truck, recommended following distance is one second for each 10 feet of vehicle length at speeds below 40 mph. At greater speeds, add 1 second. For example if the vehicle is 60 feet long, and traveling at 50 mph, seven seconds of following distance is recommended in good conditions. If the roadway is wet, double the following distance.

To measure following distance in this way, look for an overpass. When the shadow strikes the vehicle in front of you, begin counting (one thousand one, one thousand two, etc.). You should get to at least three seconds before the shadow reaches your vehicle.

Space behind. Drivers cannot control the behavior of others, including those drivers who follow too closely. Some strategies for making such a situation safer include staying to the right, increasing following distance (making it easier for tailgaters to pass), avoiding quick changes (by monitoring the road ahead at least 12 to 15 seconds), maintaining speed (it is safer to be tailgated at lower speeds than at higher speeds) and communicating with drivers by using turn signals, signaling early, tapping brake pedal, and reducing speed very gradually.

Space to the sides. Oversize loads often take up all or most of a lane. Safe drivers will manage what little space is available by keeping the vehicle centered in the lane and by avoiding driving alongside other vehicles. At least three issues are involved when traveling next to others. First, another driver may change lanes suddenly or may experience a mechanical failure such as a blown tire. This could lead to a crash when vehicles are very close together. Second, the oversize load and/or P/EVOs may get trapped when needing to make a lane change or a turn. And, third, strong winds make controlling large vehicles more difficult especially in mountainous terrain and exiting tunnels. Avoid driving alongside other vehicles.

Lead P/EVOs should alert the drivers of wide loads about guardrails, mailboxes, stalled vehicles, tree limbs, and numerous other potential obstructions. And, all drivers should avoid traveling in another vehicle's blind spots, and should adjust their speed to avoid having vehicles in their own blind spots.

Space overhead. Striking overhead objects is dangerous and expensive. Several general practices are imperative. First, never assume the heights posted at bridges and overpasses are correct. Re-paving or packed snow, for example, may reduce the clearances. Further, individual lanes may vary in terms of clearance due to the slope of the roadway and/or the slope of the bridge or overpass. In some situations, it is more difficult to clear objects along the edge of a road, such as signs, trees, bridge supports, mailboxes, guardrails, etc. If this is the case, drive closer to the center of the road. The lead P/EVOs should advise load driver of such objects and when the road is slanted to the degree it affects clearance and/or even possible shifting of the load. See also Module 5, Lesson 2.

Space below. Drivers often forget about the space underneath vehicles. This space is reduced when vehicles are heavily loaded. This problem is more common on dirt roads, when potholes exist, when roads have no shoulders, and when the roadside is lower than the road itself, creating a dangerous "lip" at the road's edge. With heavy vehicles, for example, hitting a pothole can break an axle. Drainage channels, road surfaces in work zones, and railroad crossings present significant challenges for oversize loads, especially those with low clearance. Escorts must know the dimensions of the load vehicle in order to inform the load driver of relevant hazards in enough time for the load driver to respond.

Space for turns. Wide turning and offtracking of large vehicles means the load vehicle can hit other vehicles or objects when turning. This is especially true of long vehicles that may require all lanes to complete a turn, especially on two-lane roads.

When making right turns, the P/EVO must block lanes needed by the load to complete turns. Turn slowly to give the load and other motorists more time to avoid problems. When escorting a load that cannot make a right turn without swinging into other lanes, turn wide while completing the turn, keeping the rear of the load vehicle close to the curb. This will reduce the chance that other drivers will attempt to pass on the right. Avoid swinging out to the left, however, because other motorists may think the load will turn left. Motorists may attempt to pass on the right, and the load and motorist may collide as the load completes the turn.

If the load must cross into the oncoming lanes to make a turn, the lead P/EVO should warn traffic and be in position to control traffic when the load is turning into oncoming traffic lanes. See Module 5, Lesson 4.

For left turns, the lead P/EVO should get to the center of the intersection before starting the left turn. If this lead P/EVO turns too soon, or more significantly, if the load driver does, the left side of the load vehicle may hit another motorist because of offtracking. If there are multiple turning lanes, don't start in the inside lane. The load may have to swing right to make the turn, and motorists on the left of the P/EVO and load vehicles are more easily seen.

Space needed to cross or enter traffic. P/EVOs must be aware of the load size and weight and the characteristics of the load vehicle in order to warn motorists and assist the load driver. This is apparent, for example, in the slow acceleration rate of large, heavy vehicles — the space and distance required for large loads to merge onto roadways is substantially longer than for passenger vehicles. Make sure the load has ample time to cross an intersection without blocking traffic.

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

- What is meant by the terms "hazardous conditions" or "good conditions?"

- Drivers should dim lights (from high beam to low beam) within _______ feet of oncoming vehicles or when approaching a vehicle from behind.

- When should headlights be used?

- Stopping Distance equals what?

LESSON 5: SAFETY TECHNOLOGIES

Analysis offered by the IIHS indicates that a combination of four crash avoidance features has the potential to prevent or mitigate more than one of every four large truck crashes, one of every three injury crashes, and about one of five fatal crashes if every rig had them.184

These four crash avoidance technologies are side view assist, forward collision warning/ mitigation, lane departure warning/prevention, and electronic stability control.185 These technologies are already available in many vehicles driven by P/EVOs.186

Of the four technologies, side view assist has the greatest potential for preventing large truck crashes of any severity, according to the IIHS. The technology is potentially applicable to 39,000 crashes in the United States each year, including 2,000 serious and moderate injury crashes and 79 fatal crashes.

Electronic stability control (ESC) is another promising technology with the potential to prevent or mitigate up to 31,000 crashes per year including more serious crashes — up to 7,000 moderate-to-serious injury crashes and 439 fatal crashes per year. ESC, which helps improve traction after losing the grip on the road surface, could prevent or mitigate up to 20 percent of moderate-to-serious injury crashes and 11 percent of fatal large truck crashes.

Large trucks will soon be equipped with ESC, the same technology that has slashed rollover crashes in passenger vehicles, thanks to a NHTSA requirement for ESC on heavy vehicles. The rule (49 CFR Part 571), finalized in June 2015, affects almost all new truck tractors in 2017, with some other vehicle types having until 2019 to comply.187

NHTSA estimates the ESC requirements will prevent up to 1,759 crashes, 649 injuries, and 49 deaths each year. An earlier IIHS analysis found that ESC on tractor-trailers could potentially prevent 295 fatal crashes a year, assuming the technology was 100 percent effective. Looking at all large trucks, not just tractor- trailers, ESC would be relevant to 439 fatal crashes.188

Forward collision warning systems, the third technology under study currently, identify a potential collision and warns the driver. IIHS analysis indicates forward collision warning has the potential to prevent as many as 31,000 crashes per year, including 3000 serious and moderate injury crashes and 115 fatal crashes.

Finally, lane departure warning/prevention systems, the fourth technology in this group, could prevent up to 10,000 large truck crashes annually, including 1,000 serious and moderate injuries and 247 fatal injuries.189

Crash avoidance technologies may help mitigate driver distractions (physical, visual, and mental),190 and to some degree fatigue can be monitored with these new technologies. Crash avoidance technologies show a lot of promise in reducing crashes associated with distraction whether the distraction is physical, visual, or mental.

Other Safety Technologies and Strategies

Adaptive Cruise Control uses forward-facing radar to detect a vehicle or other obstruction ahead. This helps mitigate rear-end collisions.

Automated braking systems show great potential for reducing collisions. NHTSA has endorsed automatic braking systems as one of its technological vehicle improvements and may eventually require installation of Automated Emergency Braking systems on all U.S. vehicles.

"We are entering a new era of vehicle safety, focused on preventing crashes from ever occurring, rather than just protecting occupants when crashes happen," Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx said in 2015 when announcing 10 major U.S. car companies had committed to making automated emergency braking standard on all vehicles.191

Blind spot monitoring and detection uses sensors or cameras to alert drivers when a vehicle is in blind spots.

Adaptive headlights turn about 15 degrees (creating a range of 30 degrees) as the vehicle is steered around curves and corners.

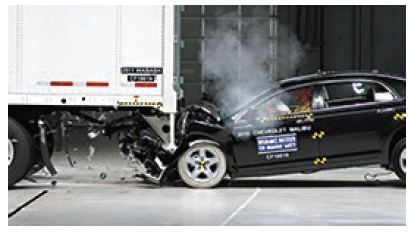

Under-ride guards are particularly important for rear P/EVOs. IIHS advocates stronger under-ride guard requirements that could prevent more deaths and injuries in rear-impact crashes.

Figure 3. Photo. Inadequate under-ride guards contribute to deaths and injuries in rear-impact crashes, as shown here.

(Source: Insurance Institute for Highway Safety)

Figure 4. Photo. Stronger under-ride guards, as shown in this photo, reduce deaths and injuries in rear-impact crashes.

(Source: Insurance Institute for Highway Safety)

Making vehicles more visible to other drivers at night. IIHS research indicates that motorists can more accurately judge the speed and distance of objects moving at night when they recognize big vehicles. Crashes involving passenger vehicles crashing into trailers from the side or rear were much more common on unlighted roads. Enhanced reflective markings are now required on all trailers, and P/EVOs should consider using retro-reflective tape on their vehicles as well.

Finally, as mentioned in Lesson 2 of this module, electronic on-board recorders (EOBR) may become required equipment, reducing driver fatigue by monitoring hours of service for drivers and making regulation more effective.

Nothing will replace driver vigilance in collision prevention, but new technologies, as well as more established technologies being placed in broader use, can further reduce collisions. When the load movement team is committed to eliminating distractions, plans for adequate rest and breaks, and sets realistic daily travel goals to avoid frustration and unreasonable time pressures, these commitments promote safe load movement.

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

- What are benefits of crash avoidance technologies?

139 Distraction.gov, "Facts and Statistics," available at: http://www.distraction.gov/stats-research-laws/facts-and-statistics.html. [ Return to note 139. ]

140 American Automobile Association (AAA), The Effects of Distractions, Drowsiness, and Emotions on Driving, 2013, p. 286. [ Return to note 140. ]

141 Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, David Kidd, PhD, Searching for the Answers to Distracted Driving, Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Joint meeting of Drive Smart Virginia and the ASSE Colonial Virginia Chapter, April 21,2015, slide 3. [ Return to note 141. ]

142 Virginia Tech Transportation Institute (VTTI), The Impact of Hand-Held and Hands-Free Cell Phone Use on Driving Performance and Safety Critical Event Risk, 2013. Available at: http://www.vtti.vt.edu/featured/?p=193.. [ Return to note 142. ]

143 Virginia Tech, "New data from Virginia Tech Transportation institute provides insight into cell phone use and driving distraction," July 2009. Available at: http://www.vtnews.vt.edu/articles/2009/07/2009-571.html. [ Return to note 143. ]

144 Ibid.; see also the Texting and Driving Safety Campaign web page, available at: http://www.textinganddrivingsafety.com/texting-and-driving-stats. [ Return to note 144. ]

145 American Automobile Association (AAA) The Effects of Distractions, Drowsiness, and Emotions on Driving, 2013, p. 286. [ Return to note 145. ]

146 Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, Driver Distraction In Commercial Vehicle Operations, FMCSA-RRR-09-042 (Washington, DC: FMCSA, 2009). Available at: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/sites/fmcsa.dot.gov/files/docs/FMCSA-RRR-09-042.pdf. [ Return to note 146. ]

147 Ian Reagan, Ph.D., "Mitigating cognitive distraction and its effects with interface design and collision avoidance systems," presentation to the NHTSA Cognitive Distraction Forum in Washington, DC, held on May 12, 2015. Available at: http://www.iihs.org/media/5978ffb2-f3dd-48b6-82aa-1552dffee776/-1702734340/Presentations/Reagan_May2015_distraction.pdf . [ Return to note 147. ]

148 This is supported by studies conducted in Canada and Australia. See David Kidd, Ph.D. "Searching for answers to the problem of distracted driving," presentation to the Joint meeting of Drive Smart Virginia and the ASSE Colonial Virginia Chapter, April 21, 2015, slide 5. Available at: http://www.iihs.org/media/d5958a09-77ab-4417-99ff-781b78c36f77/1734298945/Presentations/Kidd_201520DriveSmart.pdf. [ Return to note 148. ]

149 AAA "mperfect Hands-Free Systems Causing Potentially-Unsafe Driver Distractions," October 2014. http://newsroom.aaa.com/2014/10/imperfect-hands-free-systems-causing-potentially-unsafe-driver-distractions/. [ Return to note 149. ]

150 American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, Model Commercial Driver License Manual (AAMVA, July 2014), Section 2.9, p. 2-22. Available at: http://www.aamva.org/CDL-Manual/. [ Return to note 150. ]

151 The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), "Distracted Driving" web page. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/distracteddriving/default.html. [ Return to note 151. ]

152 Virginia Tech Transportation Institute, "New data from Virginia Tech Transportation Institute provides insight into cell phone use and driving distraction," July 29, 2009. Available at: http://www.vtnews.vt.edu/articles/2009/07/2009-571.html. [ Return to note 152. ]

153 American Automobile Association, How to Drive, "Chapter 13. The Effects of Distractions, Drowsiness and Emotions on Driving." Available for a fee at: https://drivertraining.aaa.biz/shop/how-to-drive/how-to-drive-student-manual. [ Return to note 153. ]

154 Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Highway Loss Data Institute, "Large Trucks Q and A." Available at: http://www.iihs.org/iihs/topics/t/large-trucks/qanda. [ Return to note 154. ]

155 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Drowsy Driving—19 States and the District of Columbia, 2009-2010. [ Return to note 155. ]

156 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, "Drowsy Driving and Automobile Crashes – NCSDR/NHTSA Expert Panel on Driver Fatigue and Sleepiness" (n.d.). Available at: https://www.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/drowsy_driving1/drowsy.html#V.%20POPULATION%20GROUPS. [ Return to note 156. ]

157 S.V. Masten, J.C. Stutts, and C.A. Martell. "Predicting daytime and nighttime drowsy driving crashes based on crash characteristic models." 50th Annual Proceedings, Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine, October 2006, Chicago, IL. See also National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, The Impact of Driver Inattention on Near- Crash/Crash Risk: An Analysis Using the 100-Car Naturalistic Study Data, DOT-HS-810-594 (Washington, DC: NHTSA, 2006). See also, AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, "Asleep at the wheel: the prevalence and impact of drowsy driving," (Washington, DC: AAA, 2010). Available at: http://www.aaafoundation.org/pdf/2010DrowsyDrivingReport.pdf. [ Return to note 157. ]

158 T. McCartt, L.A. Hellinga, and M.G. Solomon, "Work schedules of long-distance truck drivers before and after 2004 hours-of-service rule change," Traffic Injury Prevention 9 (2008):201-10 . [ Return to note 158. ]

159 Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Highway Loss Data Institute, "Large Trucks Q and A." Available at: http://www.iihs.org/iihs/topics/t/large-trucks/qanda. [ Return to note 159. ]

160 Visor Card available at: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/sites/fmcsa.dot.gov/files/docs/HOS%20Visor%20Card%20Oct%202013.pdf. [ Return to note 160. ]

161 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, "Drowsy Driving and Automobile Crashes – NCSDR/NHTSA Expert Panel on Driver Fatigue and Sleepiness" (n.d.). Available at: https://www.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/drowsy_driving1/drowsy.html#V.%20POPULATION%20GROUPS. [ Return to note 161. ]

162 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Features, "Drowsy Driving: Asleep at the Wheel" Web page. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Features/dsDrowsyDriving. [ Return to note 162. ]

163 From Federal Highway Administration, Pilot Car Escort Training Manual: Best Practices for Pilot Car Escorts (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2004) p. 17, citing FMCSA's Driver Fatigue and Alertness Study (n.d.) . [ Return to note 163. ]

164 Federal Highway Administration, Pilot Car Escort Training Manual: Best Practices for Pilot Car Escorts (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2004), p. 17. [ Return to note 164. ]

165 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and National Center on Sleep Disorders Research Expert Panel on Driver Fatigue and Sleepiness. Drowsy Driving and Automobile Crashes. Available at: https://www.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/drowsy_driving1/drowsy.html#V.%20population%20group. [ Return to note 165. ]

166 Ibid. [ Return to note 166. ]

167 D. Dawson and K. Reid, "Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment," Nature 388(6639):235. See also: A.M. Williamson and A.M. Feyer AM. "Moderate sleep deprivation produces impairments in cognitive and motor performance equivalent to legally prescribed levels of alcohol intoxication," Occupational and Environmental Medicine 57(10):649-55. In addition: J.T. Arnedt, G.J. Wilde, P.W. Munt, and A.W. MacLean, "How do prolonged wakefulness and alcohol compare in the decrements they produce on a simulated driving task?"Accident Analysis and Prevention 33(3): 337-44. [ Return to note 167. ]

168 M.E. Howard et al., "The interactive effects of extended wakefulness and low-dose alcohol on simulated driving and vigilance," Sleep 30(10):1334-40. See also: A. Vakulin, et al., "Effects of moderate sleep deprivation and low-dose alcohol on driving simulator performance and perception in young men," Sleep 30(10):1327-33. [ Return to note 168. ]

169 Federal Highway Administration, Pilot Car Escort Training Manual: Best Practices for Pilot Car Escorts (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2004), p. 17. [ Return to note 169. ]

170 American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, Model Commercial Driver License Manual (AAMVA, July 2014), p. 2-25. Available at: http://www.aamva.org/CDL-Manual/. [ Return to note 170. ]

171 National Institutes of Health, "How Much Sleep Is Enough?" Web page. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sdd/howmuch. [ Return to note 171. ]

172 American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, Model Commercial Driver License Manual (AAMVA, July 2014), p. 2-41. Available at: http://www.aamva.org/CDL-Manual/. [ Return to note 172. ]

173 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Aggressive Driving Enforcement: Strategies for Implementing Best Practices, (Washington, DC: NHTSA, 2000). [ Return to note 173. ]

174 American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, Model Commercial Driver License Manual (AAMVA, July 2014), p. 2-23. Available at: http://www.aamva.org/CDL-Manual/. [ Return to note 174. ]

175 175 This section is adapted from the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators Model Commercial Driver License Manual. [ Return to note 175. ]

176 It is important to remember that alcohol and some medications slow down response rates. When an individual consumes alcohol, for example, the muscles react more slowly, including the muscles in the eyes that control pupil constriction. Considering that most drinking and driving is done during nighttime hours, this means that the vision of drinking drivers is much more debilitated, especially "glare blindness" that can last much longer than drivers who have not consumed alcohol due to the slower rate of pupil constriction. [ Return to note 176. ]

177 American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, Model Commercial Driver License Manual (AAMVA, July 2014), Section 2.6. Available at: http://www.aamva.org/CDL-Manual/. [ Return to note 177. ]

178 Ibid., Section 2.6.1. [ Return to note 178. ]

179 Federal Highway Administration, Pilot Car Escort Training Manual: Best Practices for Pilot Car Escorts (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2004), p. 43. [ Return to note 179. ]

180 American Automobile Association, How to Drive: the Beginning Student Manual, 2004, p. 78. [ Return to note 180. ]

181 American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, Model Commercial Driver License Manual (AAMVA, July 2014), p.2-15. Available at: http://www.aamva.org/CDL-Manual/. [ Return to note 181. ]

182 Ibid., Section 2.13.2. [ Return to note 182. ]

183 American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, Model Commercial Driver License Manual (AAMVA, July 2014), Section 2.7. Available at: http://www.aamva.org/CDL-Manual/. [ Return to note 183. ]

184 Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Highway Loss Data Institute, "Large trucks to benefit from technology designed to help prevent crashes," Status Report 45 (2010): 5. Available at: http://www.iihs.org/iihs/sr/statusreport/article/45/5/3. [ Return to note 184. ]

185 J. Jermakian, "Crash avoidance potential of four large truck technologies," Accident Analysis and Prevention 49 (2012): 338–346. [ Return to note 185. ]

186 As mentioned in Module 1, it is important to mount the Oversize Load sign on top of the vehicle in order for the technology, installed in the bumpers of vehicles, to function. This will make roof-mounted Oversize Load signs the norm for the not-too-distant future. [ Return to note 186. ]

187 Federal Register, "Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards; Electronic Stability Control Systems for Heavy Vehicles." Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/06/23/2015-14127/federal-motor-vehicle-safety-standards-electronic-stability-control-systems-for-heavy-vehicles. [ Return to note 187. ]

188 Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Highway Loss Data Institute, "Large trucks to benefit from technology designed to help prevent crashes," Status Report 45 (2010): 5. Available at: http://www.iihs.org/iihs/sr/statusreport/article/45/5/3. [ Return to note 188. ]

189 J. Jermakian, "Crash avoidance potential of four large truck technologies," Accident Analysis and Prevention 49 (2012): 338–346. [ Return to note 189. ]

190 Ian Reagan, Ph.D., "Mitigating cognitive distraction and its effects with interface design and collision avoidance systems," presentation to the NHTSA Cognitive Distraction Forum in Washington, DC, held on May 12, 2015. Available at: http://www.iihs.org/media/5978ffb2-f3dd-48b6-82aa-1552dffee776/-1702734340/Presentations/Reagan_May2015_distraction.pdf. [ Return to note 190. ]

191 K. Laing, "Truck companies press for automatic brakes," The Hill, October 20, 2015. Available at: http://thehill.com/policy/transportation/257512-truck-companies-press-for-automatic-brakes. [ Return to note 191. ]