SAFETY SERVICE PATROL PRIORITIES AND BEST PRACTICES

April 2017

CHAPTER 3. SERVICE PATROL OPERATIONS

Considerations

Safety Service Patrol (SSP) programs should provide a frequency of coverage that supports regional or statewide incident clearance goals, which typically include reducing traffic congestion, improving travel time reliability, and improving safety on the roadway system. When implementing or expanding an SSP program, there are several factors to consider such as hours of operation, service patrol route selection, personnel availability, and the number of vehicles. It is important to consider the funding needed to deploy and maintain the number of personnel and vehicles to provide the desired level of service. Other factors to consider include identifying and designing the types of vehicles to be used, what equipment to install on the vehicles, and the tools and equipment needed to perform the service patrol functions safely and effectively.

Achieving success does not stop with defining and implementing the service patrol program. There are many policies, procedures, and multi-agency agreements required as well as strong relationships with other response agencies to allow for the proper integration of the service patrols into the Traffic Incident Management (TIM) response team. Training is paramount for the patrollers, and multi-agency training and exercises can establish relationships and trust between the patrollers and the other response agencies. These considerations are influenced by program goals, funding and resources, so it is important to keep the decision-makers and elected officials informed as to the progress and successes of the program and the benefits that are realized.

Hours of Operation

Service patrol operating hours are derived from traffic operational and safety needs based on time of day, as well as available resources.

Typical levels of temporal coverage include:

- Peak Hours Only.

- Monday-Friday, 16 hours per day.

- 24 hours per day/7 days per week.

- On-call.

At a minimum, the hours of operation for a service patrol should be peak travel times during the week or weekend during which congestion and incidents historically occur. Incidents can also impact the roadways prior to peak travel times. Starting service patrol operations prior to peak travel periods on weekdays and extending through the day beyond the afternoon (PM) peak travel period has the added benefit of removing traffic incidents and their impacts prior to the peak travel times.

The expansion to all-day operations (16 hours per day) is generally driven by traffic volumes and crash rates during mid-day, pre-peak and post-peak periods, but is also limited by available funding and resources. The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) developed a formula for determining the minimum requirements which would need to be met for a roadway to be considered for establishing a service patrol along a route. The formula involved developing an Incident Factor (IF) by relating the amount of traffic traveling along a section or limited access roadway to the number of crashes. If the IF factor calculated resulted in a number of 4.0 or greater, the roadway would be considered for SSP since the higher IF reflected greater impacts of recurring congestion on the evaluated roadway segment.

The operation of an SSP for 24 hours per day and seven days per week is generally limited by funding as well as relative need. Regions with limited traffic volume on main routes during off-peak periods and justification for SSP services must be considered in terms of the cost of operating those services for a particular route and time period. A segment that is not normally congested during particular periods may not offer justification in itself for SSP coverage. However, other considerations such as driver safety in specific areas may also be measured, for instance, assuring that a stranded motorist receives a response within a specific amount of time, such as 30 minutes.

When 24 hours per day/7 days per week services are not justified, having patrollers on call for after-hours response may allow for flexibility in addressing disablements or assisting with major incidents. This is especially applicable if incident frequency, while not justifying full coverage, may substantiate staffing for providing these limited services over sections of the roadway network.

Beginning a program by focusing on operations during morning and evening peak hours typically can provide a good assessment of SSP benefits as well as providing the maximum program visibility to the public. Expanding SSP services beyond weekday peak travel hours requires consideration of whether there is significant non-recurring congestion during off-peak periods as a result of disabled vehicles or crashes. In several large metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles and Washington, off-peak and weekend traffic on specific routes can approach or even exceed peak hour traffic levels. These conditions make it easier to demonstrate potential benefits with the expansion of SSP activities.

The following should be considered regarding hours of operation.

- When there are significant numbers of incidents that occur prior to peak periods that may warrant SSP response prior to peak periods.

- If there could be a cost savings by assisting incidents with SSP instead of dispatching maintenance personnel during off hours to assist at incident scenes, as well as benefits due to reduced response time.

- Specific crash rates on specific routes during the hours when there are no patrols operating.

- Hourly volumes and/or Level of Service along the major roadways during hours when the patrols are not operating.

Expanding the hours of the patrols can often be proven feasible, it requires proper justification to obtain the necessary funding and other approvals to implement. It is possible to increase temporal coverage of SSP through various staffing options as discussed in section 2.1 of this report. Use of the aforementioned Traffic Incident Management Benefit-Cost (TIM-BC) model or other benefit-cost comparisons based on collected data and known operational costs can assist in identifying the likely impacts of adding additional coverage both temporally and across the network. As presented in Chapter 1, the Maryland Coordinated Highway Action Response Team (CHART) Program expanded the hours of service from a 16-hour day, five days a week program with patrollers on call 24 hours per day/7 days per week during non-operating hours to a 24 hours per day/7 days per week response program in the major metropolitan areas. This was accomplished after collecting the crash rate and average daily traffic (ADT) data to show there was a need for the services and the benefits that the extended hours would bring. Pilot tests demonstrated the potential benefits of expanding services. As a result, after almost 25 years of operating the program, funding for the additional patrols for the extended hours materialized and has since brought many additional benefits to the program.

The District of Columbia DOT (DDOT) is another example of a program that has expanded their operating hours as the program has matured. DDOT initially began their program operating the patrols Monday through Friday, 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM. The initial deployment had two to three trucks on each shift. As the demand grew for their services and the added benefit they brought to the transportation system was recognized, they gradually added an overnight shift on weeknights and finally migrated to 24 hours per day/7 days per week operations with four trucks per shift.

Table 6 illustrates program examples of service patrols and their associated hours.

Prioritizing Routes to Patrol

Agencies have used different methods to prioritize which routes to patrol. Some programs patrol only freeway routes while others may patrol freeway and key arterial routes. The following paragraphs provide examples of route prioritization based on various factors such as traffic volumes during peak periods, by average daily traffic, crash rates, or some combination thereof. Regardless of the method followed to choose the service patrol routes, the choices should be focused on the agency's performance goals, expectations, finances, and resources.

Agency |

Hours of Operation |

|---|---|

|

Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) (Mile High Patrol). |

Monday-Friday 6:30 AM-9:00 AM, 3:30 PM-6:30 PM |

|

CDOT (Mountain Patrol/Heavy Tow). |

On-call based on weather and demand |

|

Florida Department of Transportation (Road Rangers). |

Varies between districts, counties, and roadways. 24 hours per day/7 days per week in most areas and roadways to only peak commute hours in others based on demand. |

|

Georgia Department of Transportation (Highway Emergency Response Operators). |

24 hours per day/7 days per week |

|

Maryland State Highway Administration (Coordinated Highways Action Response Team). |

24 hours per day/7 days per week |

|

New Hampshire Department of Transportation (I-95 patrols). |

Winter Months Monday-Friday 5:30 AM-8:00 AM, 3:30 PM-6:00 PM Summer Months Monday-Thursday 5:30 AM-8:00 AM, 3:30 PM-6:00 PM Friday 5:30 AM-8:00 AM, 3:30 PM-7:00 PM Saturday 9:00 AM-5:00 PM, Sunday 10:00 AM-6:00 PM |

|

New Hampshire Department of Transportation (I-93 patrols). |

Monday-Thursday 5:00 AM-8 AM, 3:30 PM-7:00 PM Friday 5:00 AM-8:00 AM, 3:30 PM-9:00 PM Sunday 2:00 PM-8:00 PM |

|

Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) District 8. |

Monday-Friday 6:00 AM-9:00 AM, 2:30 PM-6:00 PM |

|

PennDOT District 6 (Philadelphia Area). |

Monday-Friday 5:00 AM-7:30 PM |

|

PennDOT District 6 (Philadelphia suburbs). |

AM and PM peak only |

|

Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission. |

24 hours per day/7 days per week Routes are driven three times per shift |

|

South Carolina (Charleston, Columbia, Florence, and Myrtle Beach). |

Monday-Friday 7:00 AM-7:00 PM Saturday 9:00 AM-7:00 PM Sunday 9:00 AM-5:00 PM |

|

South Carolina (Rock Hill). |

Monday-Friday 6:30 AM-6:30 PM Saturday 8:00 AM-6:00 PM Sunday 10:00 AM-6:00 PM |

|

South Carolina I-85 (Anderson, Greenville, Spartanburg). |

Monday-Saturday 6:30 AM-7:30 PM |

|

South Carolina (Cherokee County). |

Monday-Friday 6:30 AM-6:30 PM Saturday 8:00 AM-6:00 PM Sunday 8:00 AM-4:00 PM |

|

Utah Department of Transportation. |

Monday-Friday 6:00 AM-7:00 PM |

|

Washington, DC Department of Transportation (DDOT). |

24 hours per day/7 days per week |

|

Washington State Department of Transportation. |

Monday-Friday 5:00 AM-8:00 PM, On-call 24 hours per day/7 days per week |

Pennsylvania Example

PennDOT has developed a number of criteria for selecting SSP coverage. First, PennDOT has developed a formula for determining the minimum requirements for a route to be a candidate for service patrol coverage. The initial criteria was to establish the patrols only along limited access roadways. An Incident Factor (IF), was developed for each candidate roadway segment, or unidirectional portion of roadway between interchanges, to be covered. The IF formula is illustrated in Figure 1. The IF is calculated by multiplying the average annual daily traffic (AADT) of the segment by the annualized crashes per mile for the segment which is averaged over the most recent three years of crash data. The calculated number is then be divided by 100,000 to obtain the resulting IF.

(AADT) x (average annual number of crashes/length of segment in miles)

100,000

Figure 1. Formula. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Incident Factor Formula.

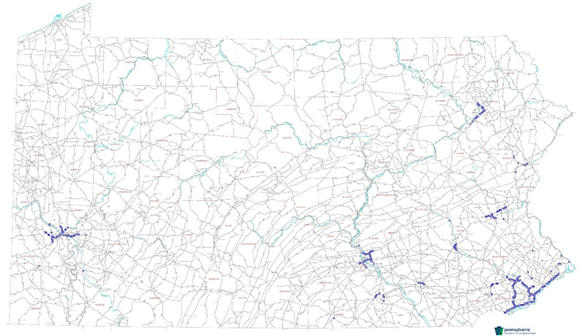

The IF related the amount of traffic traveling along a section or limited access roadway to the number of crashes. A low IF indicates that crashes are less likely to have a major impact on travel conditions. A high IF indicates that crashes may have a significant impact on traffic, especially during peak periods. Figure 2 illustrates the IF statistics map for 2005-2007. Where the IF is 4.0 or greater as highlighted by the roadways colored purple in Figure 2, the roadway will be considered for coverage.

Once the IF is determined, roadway segments are then selected to create an SSP circuit route. The criteria used are:

- Find segments meeting IF of 4.0 or greater.

- Recognize segments in the opposing direction of travel of those segments meeting the required IF.

- Classify segments which may have an IF of less than 4.0 but which connect two segments that have a minimum IF of 4.0.

- Isolate segments on logical feeder routes that connect to the Freeway Service Patrol (FSP) circuit route.

Figure 2.

Graph. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation 2005-2007 Incident Factor

Statistics Map.

Source: Pennsylvania Department of Transportation

- Other roadway segments may be reviewed and approved by the

particular PennDOT District Executive and the Director of the Bureau of Highway

Safety and Traffic Engineering (BHSTE). The segments must meet the following

criteria:

- Deemed critical for maintaining traffic flow where incidents would cause excessive delay and safety concerns.

- Identified by the planning partners as a congested corridor and included in their Congestion Management Plan (CMP).

- Measured shoulder areas less than 6 feet in width.

- Collected in groups that are less than 1-mile in length for evaluation purposes.

Finally, any PennDOT district operating an SSP program must conduct an annual benefit/cost analysis. The analysis is based on:

- Reduction in incident duration.

- Reduction in fuel consumption.

- Reduction in motorist lost wages spent in congestion.

- Annual cost of FSP program.

Roadway segments can be grouped together for analysis purposes. All benefit/cost analyses are submitted to the Director of BHSTE for review and approval. Roadways with a benefit/cost of less than 2:1 may be subject to further review and analysis.

Florida Example

The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) Road Rangers do not use a standardized methodology to prioritize routes for patrol. The legacy approach is to identify high problem/high traffic areas, such as I-4 in the Orlando area and I-95 near the Miami-Dade area. Typically, two to four vehicles are used to patrol these highly congested areas. Individual districts have been using historical crash data to prioritize patrol routes.

FDOT is working with the University of Florida to develop a Road Ranger Allocation Model to assess rural and urban areas that currently do not have Road Ranger patrols. This project will develop a model algorithm to assess which other rural and urban areas need patrols and the benefits and costs.

One observation of note, based on anecdotal data, is that the workloads for individual Road Ranger vehicles remained the same or higher on new route segments when patrols were expanded in District 7, the Tampa Bay region. The implications were that although there may not be a formal process to determine route segments for SSP coverage as with PennDOT, the expanded deployments on the added routes contained similar totals of assists as on the original routes.

Nevada Example

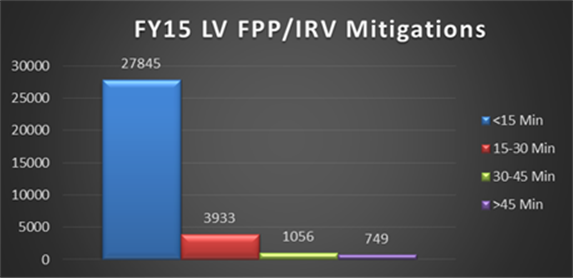

Similar to the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT), the Nevada Department of Transportation (NDOT) also looks at high problem/high traffic areas and sends patrols out accordingly. Freeway Service Patrols are typically deployed in areas that have high traffic volumes. They are charged with clearing obstructions such as debris and disabled vehicles from roadways and assisting State police with traffic control at crash scenes. Figure 3 shows the tracking NDOT used for how many vehicles were involved in the situation and the resolution for all the mitigation types.

Figure 3.

Graph. Nevada Department of Transportation Incident Mitigation Example.

Source: Nevada Department of Transportation

The performance of the NDOT FSP is currently being measured and analyzed in terms of mitigations per vehicle hour (MPVH) of each route. This metric allows for evaluation of each route and service hours of operation to ensure the most effective application of FSP and Incident Response Vehicle (IRV) resources as illustrated in Table 7.

| Service Patrol | July 2014 | August 2014 | September 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Reno FSP: Total Mitigations. |

615 |

574 |

582 |

|

Reno FSP: Vehicle Hours. |

474 |

449 |

466.5 |

|

Reno FSP: Cost. |

$30,810 |

$29,185 |

$30,323 |

|

Reno FSP: Mitigations/Vehicle/Hour. |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

|

Las Vegas FSP: Total Mitigations. |

1834 |

1590 |

2145 |

|

Las Vegas FSP: Vehicle Hours. |

2152 |

2064 |

2060 |

|

Las Vegas FSP: Cost. |

$132,348 |

$126,936 |

$126,690 |

|

Las Vegas FSP: Mitigations/Vehicle/Hour. |

0.9 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

|

Las Vegas IRV: Total Mitigations. |

668 |

690 |

714 |

|

Las Vegas IRV: Vehicle Hours. |

704 |

664 |

674 |

|

Las Vegas IRV: Cost. |

$48,576 |

$45,816 |

$46,506 |

|

Las Vegas IRV: Mitigations/Vehicle/Hour. |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

Maryland Example

The Maryland CHART Program service patrol program initially based its network on specific routes connecting to a particular region, such as the Eastern Shore. As the program evolved into a statewide program, the focus was on providing coverage on all interstate routes within the Baltimore, Frederick and National Capital regions without considering crash rates or volumes. With operational experience and evolution into a 24 hours per day/7 days per week program, average daily traffic and crash numbers have been used as criteria for expansion onto additional routes in the State.

Outfitting a Service Patrol

Once the types of patrol services have been identified, the vehicles can be specified to accomplish the service mission. The design of the patrol vehicle should start with the type of vehicle to be deployed and progress to the equipment that will be installed on the vehicle as well as carried in the vehicle. The factors to consider in the design of the patrol vehicle are:

- Cab and chassis specification.

- Body style.

- Engine and drivetrain.

- Combined weight of the vehicle including all of the equipment installed on the vehicle as well as tools and equipment the vehicle will be required to carry.

Safety equipment items such as a truck-mounted arrow board or dynamic message sign (DMS), reflective tape or decals on all four sides of the vehicles, reflective chevrons on the rear of the vehicle designed to National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standard and emergency lighting should be included on all service patrol vehicles. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Emergency Vehicle Visibility and Conspicuity Study (2009) offers particular guidance on safety and visibility for emergency vehicles.[10] Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) such as class 3 safety vests, hard hats, safety glasses, work gloves, latex gloves, hand sanitizer, and first aid kits at a minimum should be included in all vehicles. Depending on the level of service desired, it is important to identify the proper type of vehicle, equipment, and any technology that will support the expected level of service.

Choosing the Correct Type of Vehicles

The selection of the type of vehicle to use for an SSP program requires identification of the services to be provided, the types of incidents requiring response, the duties the vehicle will be performing, and the equipment that will be carried. If the vehicles will be used to push or pull vehicles out of the roadway, the vehicle needs to be designed with the proper capacity to perform those tasks. One of the challenges that face many agency response programs is designing a response vehicle capable of housing all of the equipment that is needed to manage traffic, protect the incident scene, and help mitigate the incident scene. The equipment needs to be stowed in such a manner that it is easily accessible to the vehicle operator while not becoming a hazard or projectile during rapid deceleration or if the vehicle is involved in a crash. The equipment and tools also need to be easily removable from the vehicle limiting lifting or traffic exposure hazards. Agencies have developed a wide variety of vehicle designs based on the types of equipment they carry and the missions they perform. Some agencies use more than one design to accommodate additional support capabilities or different environmental conditions in which they operate.

Overall Considerations

The vehicle design should consider the services to be provided, the environmental conditions, the equipment that will be installed on the vehicle, and other equipment carried on board the vehicle.

In developing the initial specifications of the drivetrain and suspension, there are three factors that need to be considered:

- Will these vehicles be required to push/pull/tow vehicles and large debris from the travel portion of the roadway?

- Will the vehicles be operating off-road or in severe snow or unplowed areas?

- How heavy will the vehicle be when the vehicle weight, mounted equipment and carried equipment are added together?

Vehicles that have under-designed drivetrains and suspensions are susceptible to maintenance problems and usually will not have the longevity of vehicles that are built to accommodate the load they will be carrying. To realize the efficiency and longevity of the vehicles, the vehicles should be designed for a higher capacity than might actually be required for day-to-day operations.

Engine Considerations

SSP engine type alternatives have been subject to a number of debates. Alternatives, such as diesel, gasoline or Compressed Natural Gas (CNG), have proponents and critics. The Washington State Department of Transportation is using some CNG vehicles but most use diesel or gasoline engines. Diesel engines will provide more torque for pulling, pushing, and towing, but gasoline engines generally provide better acceleration for maneuvering back into traffic from the shoulder or median of the roadway creating an added safety factor. Gasoline and diesel engine types have good longevity if properly maintained. Missouri Department of Transportation reported that they are getting 500,000 miles out of their diesel-powered vehicles.

Before deciding on which type and size of engine to use, it is recommended to compare the mileage per gallon as this could be a big factor in making the fleet more efficient. Some of the engines today have various configurations to improve the miles per gallon rating, but power must be sufficient to support the weight and performance requirements. Agency fleet maintenance providers can be of assistance in selecting a suitable engine type and size.

Cab and Body Type Considerations

The vehicle cab and body type considerations are dependent on the mission of the vehicle, the operating environment, and the equipment required to be installed inside the cab and carried on the vehicle. As with all decisions on the design of the vehicles, there are some tradeoffs to consider. Vehicles with a large cab, such as a crew cab with four doors, will allow for transport of stranded motorists to a safe location, or the ability to keep some equipment properly stowed in the rear of the cab. An extended or standard cab can also transport people, but it is not as easily accessible and it will not carry as many people as the crew cab. Another tradeoff includes maneuverability in tight spaces. The larger the size of the cab and body, the greater the turning radius and the less maneuverable it is in tight spaces such as shoulders, bridges, or tunnels.

The vehicle body type depends on the primary mission of the vehicle, the amount of equipment it is expected to carry, and accessibility to the equipment in a safe manner. Thought should be given to what equipment is being accessed the most. The driver should be able to avoid having his back to traffic while removing any equipment, or having to climb up into the vehicle and have a door blocking on-coming motorist views of the driver. The vehicle body styles include a basic utility style body with compartment doors on the side, a covered or customized utility body, a van, a pickup truck with or without a cap, or a tow truck style body. The goal is to be able to house all of the SSP support equipment in an organized and secured manner so it does not become a hazard or projectile during a crash.

Everything needs to be readily and easily accessible for ease of use and injury reduction, and certain equipment needs to be protected from the weather. For example, some programs use pickup trucks with camper shell caps. This option is applicable as long as the equipment can be secured properly and retrieved effectively and safely by the vehicle operator. These vehicles could be modified to have a pull out tray with custom racks for equipment storage and access. It is also important when designing the vehicle to leave room for growth and additional equipment that may be added in the future.

Examples

In determining the vehicle size needed, the North Carolina Department of Transportation's Incident Management Assistance Patrol (IMAP) program weighed existing SSP vehicles fully loaded and found that the weight was approximately 12,000 pounds. They decided to go with a Ford F450 one-ton cab and chassis with a utility body as illustrated in Figure 4. These vehicles are four-wheel drive and powered by diesel engines. The current models have used a 6.7-liter diesel engine in the 2009 to present model years and users have been very satisfied with this engine.

Figure 4.

Photo. North Carolina's Incident Management Assistance Patrol Vehicles.

Source: North Carolina Department of Transportation

Several programs have used more than one type of vehicle to address varying missions and priorities. The Washington State program is an example which uses different types of vehicles for different regions of the State based on different weather conditions or other operational needs as illustrated in Figure 5. In the Seattle area, where the SSP patrols floating bridges and tunnels, a Ford F450 Super Duty cab and chassis are outfitted with a tow body in order to clear stopped or stalled vehicles from the facilities as quickly as possible. Most of the other vehicles in the State use a design consisting of a Ford F450 Super Duty cab and chassis with a fully covered utility body. In rural areas, a light duty open bed pickup truck is used.

Figure 5.

Photo. Examples of Washington State Department of Transportation's Vehicle

Types.

Source: Washington State Department

of Transportation

Another example of a program with many styles of patrol and response vehicles is the Maricopa County, Arizona Regional Emergency Action Coordinating Team (REACT) program. The County performed a study that surveyed several States to determine what vehicle types might be best suited for their SSP operations. Minimum standards and functional requirements were identified. A brief description of the different types of REACT response vehicles are listed below:

Regular Responder Vehicles:

Ten of the vehicles in the REACT fleet are regular response vehicles (RRV), illustrated in Figure 6. These are one-ton vehicles with a service body and extended cab to carry emergency traffic control and support equipment. The primary role of these vehicles is to carry essential traffic control equipment and have the flexibility to quickly support the traffic control required at the incident site.

Figure 6. Photo. Regional Emergency Action Coordinating Team Regular Response Vehicle.

Source: Maricopa County Department of Transportation

Heavy Duty Responder Vehicles:

REACT has two 'heavy duty' one-ton, four-wheel drive vehicles with dual rear tires called Heavy Duty Response Vehicles (HRV). The primary role of these vehicles is to carry additional REACT traffic control equipment such as cones and light sticks that are needed for setting up longer length closures or detours specifically in support Emergency Traffic Management Operations. These vehicles also carry equipment that may not fit in the regular response vehicles and quick clearance equipment. In addition, these vehicles are also equipped with heavy duty quick clearance equipment, 50-gallon water tanks, chainsaws, leaf blowers, Hazardous Materials spill containment pools and absorbent materials, and other tools that may be needed for support at an incident scene. Newer vehicles have been proposed with shorter beds to allow for tighter turning radii on particular roads and facilities being patrolled.

Incident Command Vehicles:

Two of the REACT vehicles in the fleet are half-ton pickup trucks with camper shell caps as illustrated in Figure 7. These vehicles are also four-wheel drive to enable off-road access. They are primarily used by Incident Commanders to serve the purpose of incident command for the REACT program as well as to participate in the Unified Command. They are equipped with additional communication devices to coordinate with local Traffic Management Centers (TMC)/Arizona Department of Transportation Traffic Operations Center (TOC) and emergency departments within the County and with outside agencies. As these are supervisory or command vehicles they also carry additional equipment to document incident scenes as well as various saws, cameras, bleach, and tow straps for clearing vehicles or large debris from the roadway.

Figure 7.

Photo. Regional Emergency Action Coordinating Team Incident Command Vehicle.

Source: Maricopa County Department of Transportation

Traffic Management Center Response Vehicle:

The REACT TMC Response Vehicle (TRV), typically a van, is used for TMC response. The primary purpose of this vehicle is to provide TMC traffic management support for REACT responders and the traveling public. The responder using this vehicle activates and operates TMC systems such as signal systems, traveler information systems, and camera systems in the area affected by the incident. This vehicle reports to the TOC and serves as a spare vehicle.

Vehicle Safety Markings

A safety enhancement to consider for the patrol vehicles is the use of conspicuity tape or reflective markings on the vehicles. The reflective tape and decals or wraps need to provide reflectivity on all four sides of the vehicle to realize the highest safety standard. The greatest need for reflectivity on these vehicles is on the rear of the vehicle and uses the chevron configuration. These markings are designed to channel approaching motorists away from the vehicle thus increasing the safety of the responders as well as the approaching motorists. Examples of these markings are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 8.

Figure 8. Photo. Example of Rear Conspicuity Striping.

Source: Maryland State Highway Administration

On-Board Equipment

On-board equipment can be divided into two different categories. The first category includes the equipment mounted on or to the vehicle, and the second includes the equipment and tools carried in the vehicle. The type of equipment carried by the SSP is dictated largely by the functions which they are expected to perform as well as any agency-mandated safety equipment such as traffic safety vests, safety glasses, and gloves.

Vehicle Equipment

The vehicle equipment can aid in providing safety at the scene of an incident such as emergency lighting and an arrow board or vehicle-mounted DMS for traffic direction and management. The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) also provides direction for the use of emergency vehicle lighting in section 6I.05. Arrow boards or vehicle-mounted DMS are regulated by the MUTCD and can serve similar yet very diverse functions. The arrow boards are limited to only providing caution or traffic direction to approaching motorists via an arrow or caution mode. The vehicle-mounted DMS can also serve the traffic control and warning functions similar to an arrow board, but can be more visible and discernable due to the addition of a broader stroke on the directional arrows. The DMS also has the flexibility to post messages to support the incident or event, or provide advance warning where there is not a permanent DMS along the road.

Equipment is also available to expedite quick clearance practices using a push bumper or towing strategy to remove vehicles and large debris from the travel portion of the roadway. Table 8 provides a sampling of standard vehicle equipment used by a number of agencies.

| Special Equipment | Maricopa County REACT | North Carolina Department of Transportation | Washington State Department of Transportation | Missouri Department of Transportation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Push Bumpers |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Winches |

Yes |

Front and rear |

Some |

No |

Arrow Board |

Through Dynamic Message Sign |

Yes |

Yes |

On Motorist Assistance Vehicles |

|

Dynamic Message Sign |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

On Emergency Response Vehicles |

|

Spotlights |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Plug in for Jumper Cables |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Generator |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Air Compressor |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Closed Circuit Television |

Exploring option |

No |

Some |

No but looking into |

|

Global Positioning System (GPS) |

GPS/ Automatic Vehicle Location (AVL) |

No |

GPS/AVL |

Yes |

|

Mobile Data Terminal |

Exploring an iPad solution |

No |

Yes but not used as computer-aided dispatch |

No |

|

Backup Alarm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Hands Free Cellular |

Some |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Siren/Air horn |

Yes |

Air horn |

Both |

Yes |

|

Emergency Lights |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Radios |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Table 8 does not provide an exhaustive list of equipment installed on patrol vehicles, but it includes some of the most important items. Other types of equipment can be used, dependent on the support the patrols need in their daily functions. The following are descriptions of the vehicle equipment listed in Table 8 and the uses or justification for including this equipment:

- Push Bumpers: The push bumpers can be used to remove wrecked or disabled vehicles as well as large debris from the travel lanes to expedite the reopening of the roadway.

- Winches: Winches can be used to remove wrecked/disabled vehicles and large debris from the roadway, in particular where the circumstances do not allow for the use of a push bumper. An example of this application would be when the wheels of a wrecked vehicle are immobile due to the collision.

- Vehicle-Mounted Arrow or DMS Boards: It is beneficial for response vehicles to be equipped with either arrow boards or DMS boards as they are a primary form of traffic control for responders to inform and guide motorists through or around the incident scene. Truck-mounted DMS or arrow boards should be mounted high enough on the body of the truck to ensure that approaching drivers can see them over the tops of other vehicles.

- Spot Lights: Vehicle-mounted spot lights can be installed in a variety of positions, including in front of the driver and passenger doors, on the roof, or on a tripod after being detached from the vehicle for mobile scene lighting. The detachable lighting can be powered by a generator or portable battery pack.

- Plug-In Jumper Cable or Booster Box: The plug-in jumper cable connection offers a safer and more convenient way of jump starting batteries. Some agencies carry portable rechargeable jump start boxes in lieu of jumper cables to allow for more portability and accessibility to vehicles or equipment. Having a jumper box and jumper cables is the preferred solution to provide the portability of the box and the reliability of the cables.

- Generator: If there is room, many types and styles of generators can be deployed on an SSP vehicle. Generators can provide electrical power to the scene of an incident including powering removable scene lighting or other pieces of equipment. The generators must be mounted in a well-ventilated compartment of the vehicle or remain portable, enabling them to be used in areas that the patrol vehicle may not be able to access.

- Air Compressor: There are many types of air compressors with differing mounting configurations to suit the needs of the service patrol. Some of the compressors such as the gas-powered versions, need to be mounted on the outside of the vehicle, but there are also electric versions which can be mounted under the hood or inside of one of the compartments of the vehicle. Compressors allow the patroller to inflate low pressure spare tires for motorists. The compressors may also be used to power tools such as impact wrenches.

- Closed Circuit Television: Video capture of an incident scene and the related traffic situation can be provided to the TMC using a Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) mounted or carried in the SSP vehicle. The patroller can initiate the CCTV operation upon arrival at the scene and capture the video under local control at the vehicle or turn control of the CCTV over to the TMC to operate remotely while the patroller attends to the incident scene. The mobile CCTV provides additional information to the TMC operators to make traffic management decisions on a wider scale beyond the incident scene.

- Global Positioning System: SSP dispatchers can dispatch SSP vehicles more efficiently when they know the location of the vehicles on the roadway network. The Global Positioning System (GPS) provides vehicle location data and when coupled with Automatic Vehicle Location (AVL) technology, the SSP vehicle's location can be automatically provided to the TMC or dispatch center as the vehicle is on patrol.

- Mobile Data Terminal: A Mobile Data Terminal (MDT) provides the patroller the ability to enter information using a keyboard into MDT which is connected wirelessly to the TMC or SSP dispatch system. Information can be provided to the patroller on the MDT screen in graphical, textual or image formats providing more data at the scene for the patroller to use in response activities.

- Backup Alarm: SSP vehicles at an incident scene operate in close proximity to first responders and their vehicles. A common safety feature on large vehicles is a backup alarm that audibly beeps when the vehicle is put in reverse. The alarm warns responders near the rear of the SSP vehicle that it is backing up and to be aware.

- Hands Free Cellular: The patroller is often in communication with SSP dispatchers or TMC operators while operating the SSP vehicle. Hands Free Cellular devices facilitate safer vehicle operation by allowing the patroller to use both hands to operate the vehicle while communicating via cellular communications devices.

- Siren/Air Horn: Audible warning devices such as sirens and air horns make other roadway users aware of the SSP vehicle's presence while it navigates to an incident scene. While at the scene and conducting traffic control operations, air horns provide a method of gaining roadway users' attention when working in close proximity to or directing traffic.

- Emergency Lights: Emergency lights used on service patrol vehicles range from rotating lights to light-emitting diodes (LED) or strobes. Colors can be amber, white, red, or blue, depending on State regulations. Normally, red and blue lights denote police vehicles, and red lights denote emergency vehicles. The lighting configurations may vary from lights installed on top of the vehicle to lights in the grille and tail lights. Emergency lights provide a warning to other vehicles that the SSP vehicles are en-route to an incident scene, and if possible, vehicles should move out of the way to the let the patrol vehicle pass. Emergency lights typically require very strict usage policies to prevent misuse or abuse. Some States have installed red lights on the rear of the vehicles to allow the patrol vehicles to be eligible for coverage under "Move Over Laws." Section 6I.05 in the MUTCD provides guidance on the use of emergency vehicle lighting.

- Radios: Radio communications are the lifeline of a service patrol. Dedicated agency radio communications and standard cellular communications support reliable connectivity with the TMC or SSP dispatch center. A portable radio that the patroller can carry outside of the vehicle is also useful. Radio communications have evolved with many agencies moving from legacy communications channels to the 800 and 700 Megahertz bands. This allows for more flexibility and interoperability with police and fire/rescue agencies. If shared communications are not available, scanners can be included in the SSP vehicles so other response agency activities can be monitored providing information to the patrol operator about traffic diversion and alternate route viability.

Other Equipment, Tools, and Supplies

Table 9 provides a sample listing of the type of equipment, tools, and supplies carried by various service patrol agencies. This is not meant to be an all-inclusive list but it represents some of the items to consider including in the vehicle. It is important to identify the items which will be carried in the vehicle to ensure the specifications for the vehicle design and weight are appropriate, as well as accommodating for the safe storage and access to the tools and equipment. For example, traffic cones which are one of the most used and first deployed pieces of equipment that the patrol vehicle is carrying. The cones need to be placed in the vehicle to be easily accessible and to maximize the safety of the patroller while accessing them.

The equipment list in Table 9 is not intended to be exhaustive but meant to be a starting point for agencies to consider. The equipment carried depends on the role or level of service provided by the specific SSP program. For example, a baseline service patrol focusing on motorist assists may only require basic equipment, while a full-service SSP may train and equip their patrol operators with items such as diesel off-load pumps, chainsaws and cutoff saws for addressing crashes and hazardous materials (HAZMAT) conditions.

Technology Applications

Existing and emerging technology applications can assist patrollers with their duties and enhance their safety, as well as providing situational awareness and incident condition information to the TMC as they support incident response and management. While emerging technologies have not been implemented on a wide scale due to adoption progress, there are emerging trends toward innovative technologies which improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the SSP operation. The technologies that exist today help with the coordination between the TMCs or SSP dispatch centers and the patroller, and can facilitate inter-agency coordination and communication between the patroller and other response agencies. Example technology applications include:

- Automatic Vehicle Location/Global Positioning System applications allow SSP dispatch personnel to see where their entire fleet of vehicles is

located. When an incident occurs, the nearest service patrol vehicle can be dispatched immediately, reducing the response and clearance times for that event. This technology has other uses as well:

- Vehicle status can be tracked to include speed and routes driven. The use of the geofencing concept alerts the TMC or SSP dispatcher when an SSP vehicle strays beyond a defined area. This implementation can be used as a protective measure for the patroller, such as in a carjacking situation.

- Vehicle maintenance schedules can be linked to the

vehicle mileage or hours of operation data to preschedule or alert the fleet coordinator of the need for routine service. This facilitates an effective maintenance program which extends vehicle life.

Table 9. Types of Safety Service Patrol Vehicle Equipment. Equipment Need Employee personal protection equipment (Vest, Safety Glasses, Work Gloves, Latex Gloves etc.)

Essential

Advance Warning signs

Optional

Stop/Slow Paddle

Basic

Cones

Basic

Flares (Fuse and Battery Powered)

Essential

Light Sticks (carried by some agencies but require certain storage requirements)

Optional

Floor Jack

Optional

Lug Wrenches (standard and metric)

Basic

Tire Repair Kits (If used provide instruction)

Basic

Tire Pressure Gauge

Basic

Air Tank

Optional

Small Hand Tools (screw drivers, wrenches, hammer, wire cutters, etc.)

Essential

Battery Powered Tools

Optional

Electrical/Duct tape

Basic

Bailing Wire

Optional

Lockout Kits (Check agency policies and if allowed provide training on usage)

Optional

Jump Start Box

Optional

Jumper cables

Basic

Water for Overheated Vehicles

Basic

Gasoline

Basic

Diesel

Basic

Drinking Water and Cups

Essential

First Aid Kit (Commensurate with Training Level)

Essential

Blood Borne Pathogens Kit

Optional

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) Kit

Optional

Extra Safety Vests

Basic

Chains/J Hooks/Tow Straps/Rope

Basic

Bolt Cutters

Optional

Pry Bar

Basic

Brooms

Basic

Shovels

Basic

Trash Bags

Basic

Bucket for Debris cleanup

Basic

Flashlight

Essential

Hand Cleaner/Sanitizer and Rags/Paper Towels

Basic

Reference Manuals

Basic

Leaf Blowers (Gas powered)

Optional

Cut-Off Saw (Proper safety equipment, training and, certification if required)

Optional

Chain Saw (Proper safety equipment, training and, certification if required)

Optional

HAZMAT Plug and Dyke Kit (Training Item)

Optional

Diesel Off-Load Pump (Training Item)

Optional

HAZMAT Spill Pool (Training Item)

Optional

HAZMAT Absorbent Material (could include kitty litter)

Optional

HAZMAT Absorbent Pads or Booms

Optional

- AVL data can be linked to an Advanced Traffic Management System (ATMS) mapping database to allow for precise location of the incident scene the patroller is working. This pinpoints incident locations to support specific traffic management strategies, particularly in addressing temporary lane closures.

- Mobile data terminals are frequently used in patrol vehicles. MDTs allow the patrollers to readily access databases and information they need to perform their duties. MDTs can be connected to a Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD) System to allow reporting of incident status and conditions electronically from a specific location. A CAD-based MDT uses GPS and mapping databases for routing to an incident scene, and storing plans such as alternate routes and evacuation plans that the patroller can access from the scene. An MDT can offer the ability to see any cameras that may be available to determine the type of incident. For example, the Washington State Department of Transportation uses MDTs as a tool to transmit and receive video feeds, allowing the responders to send their onboard CCTV images to the TMC and view CCTV feeds from the TMC, prior to responding to an incident scene. This facilitates verification of the incident location and type prior to SSP arrival. In the past, MDTs consisted of laptop computers installed between the driver and passenger areas. More recently, the use of tablets provides more portability and a smaller footprint within the vehicle. Some agencies require the patroller to keep a log of their activities and MDTs can streamline the reporting process sending information in real-time to the TMC. The SSP reported data can also be incorporated into the ATMS to support traffic and incident management strategies. The MDTs can also be used for interagency response and coordination. For example, the Washington, DC area's Capital Wireless Information Network (CapWIN) allows law enforcement, fire, and transportation agencies to communicate directly on the same wireless network as well as provide access to other database resources.

- Vehicle-Mounted CCTV technology includes on-board cameras in patrol vehicles. These cameras can be permanently mounted or portable so they can be moved from one vehicle to another. Early camera applications were mounted to the windshield of the patrol vehicle as dash cameras and could send the images back to the TMC via a cellular connection for situational awareness in areas where CCTV coverage was lacking. Magnetic mounts support permanent and temporary mounting to the outside of the patrol vehicle. The newest generation of on-board cameras also provides pan, tilt and zoom capabilities, which can be viewed and controlled wirelessly from the TMC. The remote control allows the patroller to go about their assigned duties and provides the TMC operator with the camera control to view the delays or the event. Camera images can be shared with other response agencies to determine the appropriate response that should be initiated. SSP vehicles outfitted with the cameras have been used to monitor major storms providing images to the agency or emergency management for damage assessments. Agencies such as the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) and Maryland State Highway Administration (MdSHA) are successfully using CCTV technology. Transmitting video from the vehicle over a cellular connection can be costly so it is important to ensure that the agency has an appropriate data package to keep communications costs under control.

- Crowd-sourced technologies are often smartphone-based technology applications which use crowd-sourced incident data. Many agencies are entering into agreements with service providers to use and share the data to reduce congestion and delay on the regional road network. Agencies can use the incident data provided by the service provider to quickly identify an incident and, using agency resources, verify the incident data and location. The service provider-reported incident data can provide a first notification of real-time incident information. If deployed in the service patrols or in the operations center, the crowd-sourced incident data can alert the patroller of potential disabled vehicles that they may be approaching. The crowd-sourced technologies can provide a conduit to motorists for incident-related information. The Florida Turnpike Enterprise operations centers use their crowd-sourced service provider to send alerts of incident locations to motorists so they are better prepared when approaching these locations. This increases patroller and responder safety. Similar approaches are being piloted in New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont to send alerts to motorists as they are approaching snow plows along their routes. The information from the plow trucks is received by the agency and passed on to crowd-sourced service provider in real-time to alert their users.

- Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) Applications use Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) to view an incident scene and its associated traffic delays in areas where cameras may not be available. UAS applications are an emerging tool that yields potential benefits to SSP programs. UAVs can monitor traffic queues and alternate route operations.

Service Patrol Integration

The integration and coordination between SSP programs, traffic operations and other agencies is vital to its effectiveness. The following sections will discuss the approaches taken by agencies regarding coordination, policies and procedures as they affect service decisions as well as established organizational processes and structure.

Traffic Management Center Operations

The operation of SSPs complement the mission of the TMC. An important part of a successful TIM program relies on strong communications linkages between the TMC and the patrollers and an understanding of each job function and needs.

It is beneficial to cross-train the operations center staff with the SSP staff so they can form relationships and, more importantly, learn each other's roles and responsibilities during a response to a major event compared to a minor event. This provides all parties involved with an understanding of the wider perspective of the actions being taken and their involvement. When a patroller arrives at an incident scene they should be reporting to the operations center their initial report prior to exiting their vehicle. At that point the operations center staff should know that they may not be able contact the patroller for a few minutes as they are busy implementing the traffic control to protect the scene. The cross-training should include the patrollers spending time in the TOC and learning and performing some or all of the functions of the operations center operator. Consideration can be given to patrollers providing assistance in the operations center when they are on light duty assignments or cannot work in the field.

Cross-training for the operations center operators should include SSP ride-alongs to learn what the patroller duties are and to familiarize themselves with the roadway networks that they are responsible for.

It is critical that there is a trust and understanding between the patrols and the operations centers because operations centers are responsible for managing incidents and events remotely, as well as for ensuring the safety and well-being of the service patrol operators and other responders who are on the scene or responding.

To be effective, the operations center personnel need to have accurate and timely information from the patrollers or other agencies in the field, so they can accurately alert motorists of the road conditions that they may be approaching. The center operators can relay information or describe the incident scene to the patrollers or other responders if there is a camera in the area. The ability to confirm and dispatch a vehicle based on the detection and verification of an incident using CCTV provides useful information to guide the service patrol driver and arrange for other first-responders if the incident appears to contain injuries or a fire, which typically require resources well beyond that of a service patrol. Conversely, the patroller who sees a stranded vehicle also becomes a valuable part of the incident detection process by providing the incident location and details to the operations center, which can then be monitored through CCTV if available.

Policies and Procedures

A robust set of policies and procedures is crucial to guide SSP activities and responses. These policies and procedures must support patroller safety, meet the agency's expectations for performance, and inform every agency member and partner about the roles and responsibilities of the SSP. Memorandums of Understanding (MOU) between the service patrol program and other response agencies should outline common goals and operational procedures to be followed when working together at the scene of an incident.

The following are example strategies successfully used by agencies to define their Service Patrol programs. These examples serve as a starting point for an agency to consider when implementing their Service Patrol.

Inter-agency Agreements and Memorandums of Understanding

An initiative that involves a multitude of stakeholders needs a consistent set of agreements to understand the roles and goals of each organization. MOU and Inter-agency Agreements detail how each agency will interact with other agencies, as well as defining which agency takes a leadership role in different situations.

Inter-agency agreements and MOUs come in many forms. Many of these agreements already exist between transportation, law enforcement, and other agencies. In those cases, agencies need to regularly review the agreements to ensure they remain current or need revision to include new elements that are unique and/or new to the Service Patrol or TIM program. Inter-agency agreements and MOUs improve response agency coordination at the scenes of incidents.

Inter-agency agreements need to be explicit. Stakeholders need to be clearly identified, their roles and responsibilities documented, and issue resolution approaches defined. An agency will not know all of the issues it will face over time, but detailing a process to follow is the fundamental goal of the agreement. The process should include how the unforeseen situations will be considered and managed among the responding agencies. The relationships built through the process of creating the agreement are ultimately what will make the agency and their partners successful.

An example of an Inter-agency MOU between the MdSHA and other response agencies in Maryland can be found in Appendix C. The MOU outlines the responsibilities of all disciplines at the scene of an incident as well as how they will work cooperatively to get the roadway open in a safe and efficient manner. At the highest level, the agreement covers topics such as:

- Provide necessary and rapid assistance, consistent with the nature of the incident.

- Provide an integrated response.

- Provide sufficient manpower and resources to facilitate a seamless response.

- Delineate duties and responsibilities appropriately.

- Prevent injuries and destruction of property.

Standard Operating Procedures / Standard Operating Guidelines

SSPs serve as the visual representation of an agency's real-time engagement with travelers and every action, or inaction, is noticeable. It is important that the service is provided in a high quality, uniform, consistent and repeatable manner. An effective way to ensure a consistent product or service is to define actionable and meaningful Standard Operating Procedures (SOP).

An important reason for SSP SOPs is the fact that Service Patrol drivers are literally in "harm's way". By creating procedures that are designed to maximize safety and efficiency, the agency and its resources are better protected.

SOPs, also referred to as Standard Operating Guidelines (SOG), cover every activity performed by the Service Patrol program. When developing or updating the SOP/SOG it is important to remember that the content needs to align and support the agreements and response procedures of all agency incident response partners.

Some example components of SOPs/SOGs include the following taken from programs such as the Tennessee Department of Transportation's HELP Program and the Virginia Department of Transportation's Safety Service Patrol. Detailed procedures are written around each of these topic areas defining steps and actions to be taken for various situations. SOPs/SOGs are living documents that should be reviewed periodically for changes in operational approaches to incorporate changes due to lessons learned during operations and incident response including:

- Vehicle Operations.

- Patrol Operations.

- Incident Response & Clearance.

- Motorist Assistance.

- Dispatch Procedures.

- Communications Protocols.

- Standards of Conduct.

- Coordination with Partners (and Others).

Open Roads Policies

A common objective for agencies deploying a Service Patrol is rapid and efficient Incident Response and Quick Clearance. Most SSP programs focus on minimizing incident clearance times. To that end, a common practice or policy of most patrols is an Open Roads or Quick Clearance Policy. Open roads and quick clearance policies are designed to maximize all efforts towards the objective of clearing an incident from the roadway in a safe and efficient manner in order to minimize the likelihood of secondary crashes and limit the exposure of responders working around live traffic lanes. An unfortunate reality of an incident event is that secondary crashes can sometimes be more severe and lethal.

A catalyst for implementing a Quick Clearance Policy is to be compliant with the TIM National Unified Goal's (NUG) objective #2: safe, quick clearance. The guidelines and training associated with the Strategic Highway Research Program 2 (SHRP2) Reliability Program can be used as a reference or starting point. SHRP2 focuses on many objectives, but the overarching theme is safe rapid incident clearance to promote maximized travel time reliability.

Open Roads and/or Quick Clearance Policies require close coordination with other stakeholders as each agency has its own responsibilities to perform at the scene which correspond to the severity of the event. These policies commonly lead into more formal policies, which may become laws and/or statutes in many States. An example of an "Open Roads Policy" between the Maryland State Highway Administration and the Maryland State Police can be found in Appendix C.

Laws and Statutes

Laws and statutes may apply to, or may need to be expanded in support of an effective TIM program and, tangentially, a successful SSP program. Most laws and statutes that would be applicable to Service Patrols are intended to maximize the safety of those who carry out the program. Most States already have some type of law or statute associated with TIM and/or their Service Patrol. The most prevalent laws associated with Quick Clearance are those that pertain to Move Over, Driver Removal, and Authority Removal.

Move Over laws were enacted to help protect first responders working on or alongside the roadways by having motorists slow down or move over when approaching an emergency vehicle on the shoulder or in a lane of travel. The language of these laws differ from State to State. In some cases the laws cover responders with red or blue flashing lights visible from the rear of the vehicle. In many cases that could exclude department of transportation (DOT) and towing personnel. Some DOTs have designated emergency response vehicles and have gained the proper approvals to add red flashing emergency lighting to the rear of their service patrol vehicles so they are covered under the law the way it was written. Maryland passed a bill which took effect in October of 2015 which included commercial tow trucks in the "Move Over" legislation. It is very important to know and understand the way this law is written in your State and the possibilities of covering all responders to improve overall safety by requiring all travelers to "move over" or clear the lane adjacent to any service vehicle in an active response mode.

Driver Removal laws, also known as "Steer It Clear It" or "Move IT", are those that require drivers involved in a minor incident to move their damaged vehicles out of the travel lanes to the nearest safe location, if at all possible and practical. There is some ambiguity associated with Driver Removal, as drivers are not expected or desired to move their vehicles if doing so would cause further harm to themselves or others in the area. Furthermore, Driver Removal laws only apply to accidents without physical injury. In Florida, if a vehicle is blocking a travel lane, Florida law requires the driver to make every effort to move the vehicle so as not to block the regular flow of traffic. The Road Rangers provide motorists with a copy of the Florida Statute 316.061 card informing them that they may be cited for a nonmoving violation, punishable as provided in Florida Statute 318. The Road Ranger Operator is required to remain on the scene until law enforcement personnel arrive.

Authority Removal allows agencies a level of indemnification for removing vehicles from an accident scene to provide safer passage by others. Contracted service patrols can be included with the same indemnifications as long as they are not found to be grossly negligent.

There are certainly other laws associated with or relevant to Service Patrols and assisting them to meet their objectives. A good reference to learn more about the laws discussed above is the Federal Highway Administration's (FHWA) "Traffic Incident Management Quick Clearance Laws: A National Review of Best Practices."[11]

Inter-Agency Coordination and Cooperation

Inter-agency coordination, cooperation, and communication are important to overall response team success. Building the relationships and trust between the various responder agencies as well as learning each organization's roles, goals, and capabilities is paramount. There are many ways to realize this type of team building, but one of the most successful is through regularly scheduled TIM Team meetings.

Service Patrol leadership should be engaged with other agencies providing incident response. State and local law enforcement agencies, transportation and public works departments, fire departments, rescue squads, emergency medical service agencies including medical evacuation aircraft services, and towing and recovery operators are the major participants involved. There may be multiple agencies from a particular discipline involved due to geographic jurisdictions and service area boundaries. Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPO) can be instrumental in initiating and sustaining TIM team meeting platforms.

Regional TIM teams have been established to help facilitate coordination, communication and collaboration between various disciplines. These teams, groups, committees or task forces meet periodically to discuss current freeway operations, issues, upcoming construction or large-scale events. They review recent incidents and look for areas that need improvement. These meetings provide an opportunity to recognize well-coordinated incidents where all agencies have handled an incident safely, quickly and efficiently as a team.

In New Jersey, the State Police have developed an Incident Management Unit (IMU) to coordinate TIM activities across the State. This specialized unit, made up of first sergeants led by a lieutenant, are referred to as Regional Incident Management Coordinators (RIMCs). The RIMCs are a major part of New Jersey Department of Transportation's (NJDOT) TIM strategy and assist in providing TIM training and outreach to other law enforcement agencies regarding inter-agency coordination efforts as well as special event coordination. The RIMCs respond to major traffic incident scenes which are two hours or longer with a representative of NJDOT's Incident Management Response Team (IMRT) to coordinate mitigation and clearance of the incident scene with all response agencies. The IMU coordinates activities with NJDOT and other agencies in the development of detailed diversion plans, promotion of statewide incident management initiatives, and support of the New Jersey goal of "Keeping the Traffic Moving".

In order to promote inter-agency coordination and cooperation, each agency should have a clear understanding of the other agencies' capabilities, staffing, response times and operational procedures. Operating guidelines should be shared and compared and any operations that conflict should be discussed and modified until all agencies are operating under the same general protocols. Each agency should clearly understand their roles and responsibilities at incident scenes and agree to an incident command structure and unified command protocols. TIM team meetings are valuable forums for discussing procedures and developing common terminology, response guidelines, and incident command systems.

Meeting frequency is flexible. In the early stages of a new team, monthly meetings will help organize the group, set up roles and responsibilities, designate leadership positions, develop goals and objectives, organize task groups for special needs and set meeting agendas and schedules. Once organized and functioning, meeting frequency should be at least quarterly to foster and promote networking, communication, and coordination. Service patrols should have representatives available to meet with the group on whatever schedule the members agree to follow.

In addition to meeting and developing regional response procedures, TIM team meetings can also be used for joint training events. Tabletop exercises are an excellent way for multiple agencies to learn about each other's capabilities and procedures. Simulated incidents with specific problems built in can be used to develop procedures that all agencies can follow. These meetings can also provide an effective forum for after-action reviews for incidents that have already occurred addressing what went well, what needs to be improved, who needs to be informed, and what follow-up is needed. Success stories should be highlighted and the discussion used to reinforce the positive aspects of how the incident was handled.

Service patrols are important regional resources for highway incident response. Each patrol needs to be represented on TIM teams in their region. Service patrols can also take a leadership role in establishing new TIM teams where they do not already exist. TIM teams are the most efficient way to establish and maintain ongoing inter-agency coordination and cooperation.

FHWA's "2010 Traffic Incident Management Handbook Update"[12] has an entire section devoted to TIM Teams that can be helpful for regions that do not currently have a team. In Section 2.3 "Multi Agency TIM Teams/Task Forces," the handbook states, "Every effort should be made to designate a Service Patrol senior manager as the steady representative on a regional TIM team. It is important that the representative know the service patrols operations and procedures and that they can speak on behalf of the patrol. It is important that the same people attend meetings regularly to provide for consistency and an effective network."

Training

The level of training for service patrol programs depends on the level of service that the patrol is expected to provide. Cross-training and operational exercises with responder agencies builds trust, relationships, and knowledge of each organization's resources and capabilities. The FHWA has developed training curriculum through the SHRP2 program entitled the "National Traffic Incident Management Responder Training Program" which combines classroom training with tabletop exercises.

Service patrol capabilities, staffing, and equipment vary widely across the country. There is no national standard or guideline for service patrol training requirements. Each agency is responsible for developing its own training program content, goals, objectives and delivery model. Service patrol operators must be capable of performing a number of different duties and the training they receive is critical to their ability to operate safely and properly in any number of different situations.

A service patrol training program should cover all areas of operation, procedures, and documentation, and should include general subject areas, such as:

- General Information.

- Personal Safety.

- Communications.

- Traffic Incident Management.

- Motorist Aid.

- Vehicle and Equipment Operation.

- First Aid/CPR/Automated External Defibrillator (AED).

- Regional Protocols.

- Legal Liability Issues.

Each of the subject areas should include the various topics that need to be addressed in each agency. For example, the Traffic Incident Management section might include topics such as:

- Work Zone Traffic Control (MUTCD Chapter 6 and/or State Supplement).

- Traffic Incident Management (SHRP2 TIM 4-Hour class).

- Traffic Direction & Control (Flagger techniques).

- Human Factor & Traffic Controls.

- Liability Considerations.

Patrol operators should complete the SHRP2 TIM & Responder Safety Training Program offered nationwide. The class is designed for all highway incident responders and is intended to be delivered to mixed audiences with representatives from each responding agency in the region. It is advisable to include joint training with TOC personnel and any central or regional dispatchers used by the service patrols. All agencies should be using the same terminology while responding to incidents, for example the same lane numbering system.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) published a new standard in 2015 that will be useful for agencies that want to design their own training programs for traffic incident management. NFPA 1091 (2015): Standard for Traffic Control Incident Management Professional Qualifications[13] provides job performance requirements for anyone in any discipline that provides traffic control at incident scenes.

Worker safety topics should include all appropriate Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requirements such as Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), Hazardous Materials Awareness, blood borne pathogens, and other topics as required by OSHA or State-specific OSHA plans. The topics will vary by State and by service patrol depending on the level of services provided. The FHWA manual "Field Operations Guide for Safety/Service Patrols"[14] offers a starting point for developing an appropriate training plan for service patrol agencies.

Training programs should take into consideration the needs of new employees prior to field deployment and the training needs of all other employees as part of an annual in-service training curriculum. Some subjects, procedures and protocols should be reviewed at least annually and in some cases more frequently.

While there will most always be some classroom-style training, it is important that service patrol operators also get hands-on experience while being mentored by a more experienced operator. Most programs require new operators to ride along with, and be trained by more experienced staff. In addition to on-the-job training in the field, tabletop exercises develop for new operators a sense of potential hazardous situations, so they can anticipate protecting the scene while allowing traffic to pass the incident in a controlled manner. With tabletop exercises, various types of situations can be simulated. Experienced personnel, using small die cast vehicles, can coach operators how to position their response vehicles, and where to deploy temporary traffic control devices. The instructor can introduce something unexpected such as a secondary crash, disabled equipment, weather that is changing like fog, snow or rain, or other variables that can change the nature of a highway incident quickly and with little warning. Students learn to identify and anticipate hazards and develop a sense of how to deal with unexpected situations in a controlled environment and in the safety of a classroom.

Proper records of training offered and completed should be maintained. Each class should have a document that states the date and title of the class, location, instructor name, information covered, amount of time spent on the subject, a list of attendees with their signature, and a copy of any handout material with a list of any references used. Service patrol operators should also keep track of their own training records and notify management of any training that is out-of-date or needs to be renewed. This is especially important when tracking OSHA-required training classes or certifications with expiration dates such as CPR/AED, Commercial Driver's License (CDL), or driver's license. Annual or recurring training may be required as well in specific topics such as CPR, traffic safety, and incident site management.

[10] Emergency Vehicle Visibility and Conspicuity Study, FA-323, Federal Emergency Management Agency, August 2009, https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/fa_323.pdf [Return to Note]

[11] Traffic Incident Management Quick Clearance Laws: A National Review of Best Practices, Federal Highway Administration, December 2008, FHWA-HOP-09-005 [Return to Note]

[12] 2010 Traffic Incident Management Handbook Update, Federal Highway Administration, 2010, www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/eto_tim_pse/publications/timhandbook/index.htm [Return to Note]

[13] "NFPA 1091: Standard for Traffic Control Incident Management Professional Qualifications", National Fire Protection Association, 2015 [Return to Note]

[14] "Field Operations Guide for Safety/Service Patrols", FHWA, 2009 [Return to Note]