FHWA Freight and Land Use Handbook

4.0 Accounting for the Impacts and Needs of Freight

4.1 Purpose and Content

While the private and public sectors try to respond to rapidly and ever-changing industry needs, the transportation planning community wants to better guide transportation investment to support economic and freight needs. States and regions are identifying ways to increase their ability to compete regionally, nationally, and globally. This includes coordinating investment to support new industries and understanding their changes in land use patterns and freight transportation needs. It is important for freight to be a “good neighbor” in its host communities, as described in the previous section, and land use and zoning policies also have to account for the needs of freight transportation. These needs include access, on-site circulation, building size and use needs, geometric requirements for trucks and/or railcars, adequate truck parking and loading areas or sidings and/or working tracks for railcars, and security provisions. Freight and community needs are not necessarily mutually exclusive. In fact, the needs of the private-sector freight community may align well with local and regional sustainable development strategies. Concepts such as industrial preservation, brownfield redevelopment, and freight villages, presented in Sections 2.0 and 3.0, could serve as “common ground” strategies through which the needs and aspirations of freight and planning agencies and stakeholders can be achieved. This section will provide an understanding of freight needs, land use and transportation planning practices, and opportunities to implement sustainable freight land use and transportation strategies.

Section Organization

This section is divided into the following three sections:

- Freight Carrier/Shipper Land Use Needs – Identifies the site selection criteria and site design features that are required for safe and efficient freight operations.

- Land Use and Transportation Planning Tools to Address Freight Needs and Impacts – Examines the transportation and land use planning processes and identifies strategies and action steps aimed at engaging private-sector stakeholders and incorporating freight needs into the planning processes.

- Putting It All Together – Demonstrates, through a series of detailed case studies, how cities and Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPO) have addressed freight needs and incorporated sustainable principles into their land use planning processes.

4.2 Freight Carrier/Shipper Land Use Needs for Efficient and Safe Goods Movement

Freight shippers and carriers have a variety of needs that, if not met, can have critical impacts on efficient and safe goods movement. This section focuses on the nexus between freight needs and land use planning and activities, which is followed by a discussion on how to take action at the local, regional, state, and private-sector level to address these needs through various methods and through integration into plans and processes. Shipper and carrier land use needs vary by region and activity type.

Transportation and Logistics Physical and Operational Needs – Capacity and Reliability

The most fundamental physical requirements for conducting freight operations are adequate freight system capacity and maintenance. This includes both capacity and maintenance on general freight infrastructure (such as interstate highways and railways) as well as in terminals and logistics centers such as rail yards, seaports, airports, and distribution centers. In this discussion, capacity refers primarily to freight system congestion and proper maintenance to facilitate the movement of goods to improve speed and reliability and reduce costs. Low congestion and proper maintenance are critical to shippers and carriers, as these factors impact travel time and reliable operations, and therefore impact cost for both industries and consumers. In areas where congestion and deteriorating infrastructure are the norm, the reliability of the system is eroded and the costs of moving goods between locations will increase. As a result, it is necessary to provide adequate capacity and to adequately maintain the freight system for all applicable modes in order to improve freight efficiency.

Example of Site Selection Criteria – Roanoke Region Intermodal Facility Roanoke, Virginia

In order to provide both east-west and north-south capacity for freight rail traffic and to improve multistate freight rail facilities, as a part of the Heartland Corridor initiative, Virginia committed to building a new intermodal facility in the Roanoke region. A report was prepared which reviewed 10 sites and made recommendations on where to locate the facility based on the following evaluation criteria:

(a) Proximity and easy access to a major highway (Interstate 81);

(b) Located on the Heartland Corridor’s rail line to ensure a competitive time advantage for freight shipments;

(c) Sufficient land available (65 acres minimum if possible), an appropriate site configuration for freight transfer operations, and located on relatively flat topography;

(d) Does not create the need for additional grade separation bridges, particularly in congested urban areas;

(e) To the extent possible, seek to minimize associated roadway costs that might be required; and

(f) Well configured from a rail operating perspective to avoid degrading other rail traffic, result in more efficient rail intermodal operations and result in lower relative facility development or delivery costs.

This provides an idea of the types of variables that developers may take into consideration when selecting a site for a freight facility such as an intermodal facility.

Source: Roanoke Region Intermodal Facility Report, March 2008.

Suitable Land for Freight Activities

Land is an important resource required for all freight transportation activities. A lack of available industrial land can create overcrowded existing facilities or may encourage companies to search elsewhere for locating their business. It also is important that land is available at the right locations. For example, in port communities, some waterfront land near urban centers should be protected for freight uses or port expansion (if feasible) in order to keep goods close to market and to reduce truck or rail travel time and emissions.

Some of the key desired characteristics of land for development include:

- Access to key markets within a given radius;

- Interaction with the transportation network, meaning efficient and logical connections to interstate highways, railroad terminals, and/or major seaports and airports;

- Workforce availability, skill, and cost;

- Cost environment, including freight and logistics costs, labor costs, utilities, facilities costs, and business, real estate and, in some states, personal property taxes;

- Availability of suitable facilities or developable sites;

- Cooperation from local, state, and Federal agencies regarding permitting and regulations;

- Availability of public assistance and incentives; and

- Perception of low or reduced risk of natural hazards or climate change impacts. (NCFRP 23, Preliminary Draft Report.)

An inventory of land for development potential is critical information for private-sector stakeholders looking to develop, redevelop, expand, or relocate their facilities. In turn, it is important for local and regional governments to take the above freight selection criteria into account when selecting which land to make available for freight-dependent uses.

Adequate Loading and Staging Zones, Parking, and Enforcement

Freight carriers rely on adequate loading zones and parking to support loading and unloading of goods at freight facilities. Generally, three types of freight facilities exist which have differing loading zone and parking requirements: urban business districts, warehouses and retail centers, and intermodal or marine terminals.

Urban Business Districts

In urban environments in large cities and small town downtowns, where loading docks often do not exist, loading and unloading activities tend to occur curbside or in alleys. Management of the curbside loading/unloading freight activities are typically defined by local zoning or other ordinances. Commercial loading zones tend to be located in front of commercial buildings with designated signage for the loading zone. Curbside loading zones may be enforceable during certain periods of the day, corresponding with business hours or off-peak delivery periods. Alleys also are points of access to commercial facilities, refuse pick-up, and deliveries at the rear lots. Many alleys are narrower than a two-lane street and may not be wide enough to accommodate tractor-trailer combinations, or may only handle traffic in a one-way pattern, with little or no room to turn around or back into a loading dock or bay. An alley may therefore be “blocked” when a delivery or pick-up is in progress. Some key considerations for managing urban loading areas include:

- Establish loading zones in areas that are as close to the receiving areas of shipping/receiving businesses as possible to reduce delivery/pick-up time and disruptions to pedestrian and vehicular traffic that could result from moving goods to and from the truck.

- Make sure commercial loading zones are designated as being available when demand is highest. Whether deliveries on a particular street tend to occur during normal business hours or during certain off-peak-periods, the commercial loading zones should be made available to meet the demand. Depending upon the other land uses present in the neighborhood, there may be competing demands for curb space (i.e., shoppers and business patrons may need on-street parking during business hours, while residents may demand on-street parking overnight). Commercial loading zones should be established to meet freight needs while being sensitive to other demands for curbside space.

- Enforcement of parking and loading rules should be strict. To ensure that curbside and alley loading space is used effectively without impacts to traffic operations and safety, enforcement of parking and loading rules is critical. Enforcement of vehicle types allowed to park or stand in the loading zones, time limits, and metering discourages parking by passenger vehicles in these loading zones, and encourages trucks to occupy the space for the shortest period of time possible, ensuring that space is available for other trucks. When trucks are unable to find an appropriate place to load or unload, they may find alternative means of making their deliveries or pickups by double-parking, blocking travel lanes or driveways, or parking in other configurations that disrupt traffic flows and could present unsafe conditions for passing traffic.

Figure 4.1 Managed Curbside Loading Zone in New York City

Suburban Retail Centers

In suburban retail centers, such as shopping centers, shopping malls, big box retailers, etc., there is typically more space available to provide adequate loading/unloading and parking areas for trucks. Often, however, retail center site plans are developed with the “customer experience” as the top priority, while freight access, loading areas, and truck parking areas are considered as an afterthought.

Key considerations for freight loading and parking at suburban retail facilities include:

- Ensure adequate loading dock space for receiving deliveries and for staging outbound shipments. Anticipated shipment volumes should be considered in the design process. If a possibility that more than one truck may have to pick up or deliver goods at the same time, multiple loading bays should be provided to serve them. Within the building, space for staging outbound shipments and receiving inbound shipments should be provided to expedite the process and to keep trucks at the loading docks for the shortest period of time possible.

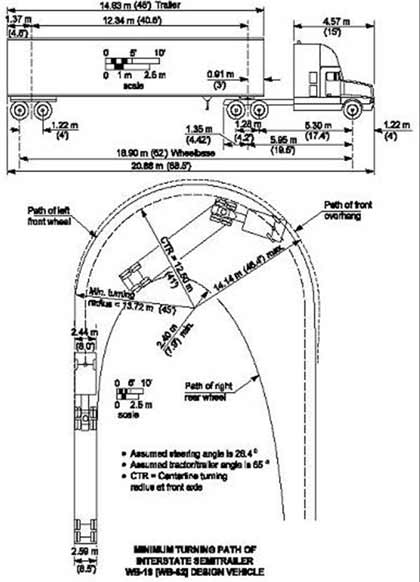

- Ensure adequate space for truck maneuvering. Providing adequate space for the largest trucks that will serve the facility is a critical consideration that is sometimes ignored. It is important to consider the size of the trucks that will serve the facility. Will all deliveries be made by vans or small box trucks, or will 53-foot trailers need to be accommodated? A tractor-trailer combination with a 53-foot trailer can measure between 70 and 75 feet in length, and require large turning radii and space to move into align the vehicle with the loading bays and back-in or pull-out. The minimum turning radii for a 68.5-foot tractor-trailer combination is shown in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 Minimum Turning Radius Requirement for Interstate Semitrailers

- Limit interaction with passenger vehicles. To the extent possible, opportunities to segregate freight traffic with passenger vehicle (customer) traffic on-site should be taken. Loading areas should be located at the rear of retail buildings, away from customer parking and entry points. Loading and customer parking areas may be accessed using separate driveways or access roads.

- Provide space for trucks to park while awaiting loading or unloading. If a truck arrives prior to its scheduled delivery window, and it cannot pull up to the loading dock due to the presence of other trucks or because the facility staff are not ready to receive the truck, it will need a place to park and await service. A designated parking area should be provided on-site for this purpose.

Warehouse and Distribution Centers

Warehouses, where goods are stored until demanded, and distribution centers, where goods are packaged, broken-down, or otherwise prepared for shipment to retailers or directly to consumers, are facilities designed for the receiving, handling, and shipment of freight. Warehouses and distribution centers may be located in urban, suburban, or rural areas, and may be served directly by truck, rail or both. While most warehouses and distribution centers are designed and developed by companies that are experienced in industrial design and understand freight needs, there are several key considerations that public-sector officials should be sure to check for in site plan reviews.

- Segregate truck and rail traffic. If a facility is being served by truck and rail, it is important to separate the two modes to the extent possible. Trucks and railcars should be served in separate loading dock areas. In some facilities, railcars and trucks are served from the same loading areas (see Figure 4.3). Such an arrangement causes conflicts, since all of the truck trailers must be moved out of the way in order for railcars to be moved along the track paralleling the loading docks. If a truck access route crosses a rail spur or working tracks, trucks may be subjected to lengthy delays as trains are broken-down, built, or as individual railcars are being positioned. Keeping the truck and rail circulation and working areas separated eliminates the conflicts between the two modes and allows both to operate as efficiently and safely as possible.

- Ensure adequate loading dock/rail shed space. Sufficient loading docks for truck deliveries and rail sheds, which consist of spur tracks and loading docks where railcars can be loaded or unloaded, should be provided for truck-served and/or rail-served facilities. Anticipated facility throughput volumes for each mode should be considered in the design process to ensure that sufficient space for delivery of inbound freight, and pick-up of outbound freight can be handled efficiently, so that trucks and trains do not have to idle for long periods, waiting for dock or rail shed space to become available.

- Ensure adequate space for maneuvering. Providing adequate space for trucks to move into and out of the loading docks and to circulate through the facility’s driveways and access routes is critical. Plan for sufficiently large turning radii and space to move into align the vehicle with the loading bays and back-in or pull-out. The minimum turning radii for a 68.5-foot tractor-trailer combination is shown in Figure 4.2.

- Ensure adequate space for drilling railcars. Space for railcars to be handled should also be provided if the facility is being served by rail. The activities of positioning, linking, and breaking-down blocks of railcars are referred to as “drilling.” In addition to rail sheds for loading and unloading, working tracks where blocks of arriving railcars can be broken down, and where departing railcars can be linked and prepared for pickup should be provided at or as near to the facility as possible.

- Provide space for trucks to park while awaiting loading or unloading. Designated parking areas for trucks to park while awaiting their delivery window should be provided on-site.

Figure 4.3 When Truck and Rail Access Are Not Separated, Inefficiencies (Such as the Orphaned Railcar Shown, Center) Can Impact Operations

Source: Cambridge Systematics, Inc., 2008.

Intermodal and Bulk Transload Terminals

Intermodal terminals are facilities where containerized cargo is transloaded from truck to rail, or vice versa. Bulk transload terminals are facilities where bulk commodities such as aggregates, liquids, gases, and agricultural products, are transloaded from truck or pipeline to rail, or vice versa. These are controlled access facilities for large scale freight operations, which are intended to be accessible by large trucks and long-unit trains. Bulk transload terminals may only require a few acres of land, on which bulk materials are piled or stacked. Intermodal terminals may occupy dozens of acres, with staging areas for trucks or chassis, container storage areas, and working tracks served by cranes. Developers prefer long working tracks of 1,500-2,500 feet in length so that long-unit trains can be assembled and dissembled with few moves.

Marine Terminals

Wait times at such facilities can be long because of high volume during peak pick-up times, drayage movements within the facility, a thorough security process or for other reasons. As a result of these waits, parking turnover rates can be low, which may require the facility to need a high number of parking spaces. Use of electronic data interchange, automatic vehicle identification and equipment tracking technologies can significantly reduce the wait times at the gate and improve the parking and loading area capacity.

Geometric Site Design of the Freight System

It is important for trucks to be able to move efficiently and safely between their origin and destination points. Many smart growth principles suggest that new neighborhoods be developed with narrow roads, which may have an impact on how effectively trucks move. Height restrictions on trucks vary by state, but usually range between 13.5 feet and 14 feet. The national maximum weight standards for interstate highways are 20,000 pounds for single axle, 34,000 pounds per tandem axle, and a gross vehicle weight not to exceed 80,000 pounds. On state and local roads and older bridges, weight limits could be much lower. (“Commercial Vehicle Size and Weight Program,” FHWA.) As a result, it is important that freight carriers are aware of height, size, and weight restrictions when moving through different neighborhoods. It also is important for local, regional, and state governments to take into account the size and height of trucks that move through its boundaries early in the planning process. Engaging in a Context Sensitive Solutions (CSS) approach, as described in Section 2.0, which seeks to arrive at solutions that meet the needs of all stakeholders is an approach that FHWA advocates.

Truck dimensions must also be taken into account in industrial, commercial, and freight facility site design. Roadways and driveways within these sites must allow for safe and efficient passage of trucks. Key considerations include:

- Ensuring sufficient turning radii. Internal roadways and driveways where trucks are intended to have access must be designed with the minimum turning radii shown previously in Figure 4.2.

- Vertical clearance. A minimum clearance of 12 feet, 6 inches should be provided for truck-served sites, with many design guidelines calling for clearances over 13 feet. Rail clearances vary depending upon the type of railcars served. Tanker and hopper cars require clearances as low as 15 feet, while double-stacked intermodal containers require a 22-feet, 6-inch clearance. Bridges, tunnels, overhead utilities and signage, and tree limbs on a truck-served site should be designed to provide sufficient vertical clearance for safe truck movement.

- Avoid “blind corners.” Landscaping, building dimensions, and utility infrastructure can hinder visibility and create potentially dangerous situations when drivers in two or more vehicles are unable to see one another. Sites should be designed to ensure that drivers can see where they are headed and so they can identify potential hazards such as oncoming vehicles in advance.

Truck Parking and Rest Facilities

The need for truck parking/rest area facilities differs from the earlier parking discussion. This paragraph refers to truck parking facilities along major truck routes and near major freight hubs such as air cargo airports, seaports, and clusters of warehousing/distribution centers and manufacturing facilities to allow truck operators to take breaks and rest while enroute between their origin and destination points. While the need for truck parking/rest area facilities is obvious in order to improve safety for truck operators and for those sharing the road with trucks, land must be made available along major routes to support the projected increase in trucks using highways. A lack of designated truck parking areas can lead to parking in unsafe areas such as highway shoulders, expressway ramps, and desolate parking lots. Parking demand can be met with publicly owned and operated, roadside parking and rest areas, or by off-freeway privately owned truck stops, which typically provide additional services such as restaurants, showers, tractor maintenance and repair services.

State DOT or other highway authorities are typically the lead agencies involved in on-highway truck parking and rest area planning and development, and should work with private stakeholders to confirm truck parking demand and identify opportunities to expand capacity where necessary. Off-highway, municipalities must work with regional and state governments and the private sector to identify opportunities to expand truck parking capacity by utilizing land around freeways and other strategic locations. Public-sector officials also may work with the private sector to incorporate space for truck parking/rest area into the design of industrial and commercial facilities. Some major national retailers, such as Wal-Mart, allow truck drivers to park in their store and distribution center parking areas at many of their stores and distribution centers. Such a parking area could be provided adjacent to the loading area, or in the general (customer) parking area during late night hours if the store is closed or experiencing light volumes of customer traffic. Implementing an arrangement for allowing trucks to park on-site may introduce liability and security issues that are unique to state and local laws and conditions, and which will have to be examined and addressed carefully.

One of the key challenges to developing new truck parking capacity is overcoming the impacts that truck parking facilities may have on adjacent residential areas. Because truck parking demand peaks during the overnight hours, the noise, light, and emissions impacts affect residential areas when peace and quiet are desired most. This challenge can often be overcome with smart site selection for truck stop and parking area development, and with implementation of design features to reduce spillover of light and noise. Many truck stops and truck parking facilities are equipped with idle-reduction equipment that allow truck drivers to run electronics and control the climate within their cabs without idling the engine. These technologies reduce fuel consumption and emissions while trucks are at rest. Vendors supply many of the nation’s truck stops and rest areas with stationary power hookups, some of which include Internet and entertainment hookups as well. Many truck stops offer recharging stations for trucks equipped with on-board power units. Agencies should work with motor carriers to take advantage of opportunities to equip fleets with on-board units, and with the agencies and companies that operate rest areas truck stops to make electrification and recharging hookups more widely available. (The U.S. Department of Energy web site has a truck stop electrification locator to help planners and motor carriers identify truck stops equipped with electrification technologies.)

Examples – Extending Hours of Operation at Freight Facilities

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) also suggested the extension of hours of operation at freight facilities to reduce peak hour congestion. Examples cited by GAO:

In New York City, some retail stores have extended hours of operation to receive deliveries after 9:00 p.m. and the City, in turn, has provided incentives to these businesses in the form of special approval of curbside parking for deliveries during off-peak hours.

The Off-Peak program and a fee concept together are implemented through PierPASS Inc. at the San Pedro Bay Ports. All international container terminals at the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports implemented five new shifts per week – Monday through Thursday nights, and during the daytime on Saturdays. In addition, a Traffic Mitigation Fee was created, and is required for cargo movement through the ports during peak hours (Monday through Friday, 3:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.). This fee is used as a congestion pricing mechanism providing an incentive to use the off-peak shifts.

The extension of hours of operation at freight facilities can reduce peak hour congestion, but requires the participation of shippers and receivers, who make the decisions regarding when deliveries are to be made. Motor carriers must make deliveries when their customers demand them. For off-peak delivery programs to be successful, those customers must be willing to have staff available or make arrangements to give motor carriers access to their facilities to make deliveries during these off-peak periods.

Source: GAO-08-287 “Freight Transportation: National Policy and Strategies.”

Flexible Timelines for Delivery/Pick-up

Extending the business hours of operation of freight handling facilities creates the opportunity to shift trucks from most congested peak hours of traffic to off-peak hours. Peak-hour congestion results in increased travel times, decreases in the reliability of deliveries, and in turn disrupts delivery schedules and inventory control operating plans in warehousing and distribution facilities. Flexibility in delivery times gives carriers the opportunity to more efficiently utilize the existing highway infrastructure. Flexible delivery times for terminal operators allows for more efficient utilization of freight handling equipment. Receivers that can typically accommodate off-peak deliveries include restaurants, convenience stores, 24-hour big box retailers and grocers, and industrial facilities with two or three labor shifts. Many small businesses which have one labor shift during business hours are not always able or willing to arrange to have staff on-site to receive a delivery during off-peak hours. An off-peak delivery pilot program completed in New York City in 2010 showed that many small receivers were willing to receive deliveries off-peak with the help of small cash incentives or by providing drop-key or key-code access to trusted motor carriers so the deliveries could be made without the receiver’s staff being on-site. (New York City Department of Transportation, “NYC DOT Pilot Program finds economic savings, efficiencies for truck deliveries made during off-hours,” Press Release # 10-028, July 1, 2010)

Safety and Security Considerations

It is important that safety and security of the public and of goods are taken into consideration when designing terminals and other facilities that ship or receive freight. Intermodal terminals, warehouses, distribution centers, and many industrial facilities are areas where trucks, trains, forklifts, cranes, and other moving pieces of equipment represent potential hazards to workers if precautions and appropriate protocols are not followed. Mishandling of hazardous materials could result in safety risks to the general public beyond the confines of the facility. Failure to secure facilities and goods from theft or vandalism could result in damage to property and harm to facility employees or the public at large. Important attributes to consider include:

- Keeping unauthorized persons away from the freight activities. Whether in a retail center where the public have access to portions of the facility, or in a freight terminal where the public are not generally permitted, it is important to ensure that people who are not authorized to be in a working freight area are not permitted to enter. Trespassers run the risk of being harmed if they are unfamiliar with the facility’s configuration and potential hazards. Fencing, signage, cameras, and security personnel may be utilized, as appropriate, to protect the facility and discourage trespassing. Some large facilities may effectively separate one part of a community from another. Facility developers and local officials should work together early in the project development process to identify any opportunities to provide alternate means of access (pedestrian bridges over rail yards, pedestrian crossing signals at signalized driveways, etc.) where appropriate.

- Ensuring that there is a designated space for each activity occurring at the facility (processing, shipment consolidation, receiving, loading/unloading, transloading, etc.) to occur safely and without the interference of other activities. When multiple various activities compete for space, equipment, and personnel, product may be left in locations where they do not belong, increasing the risk of accident, misshipment, or damage. Furthermore, loading areas, access routes and driveways, and parking areas should meet geometric guidelines to limit potential conflicts.

- Terminal/Facility operators must develop a plan with first responders. Depending upon the size and nature of a facility’s operation, the operators should work with first responders, port authorities, the Department of Homeland Security, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and other applicable local, state, and Federal agencies to develop a plan of response to terrorism, natural or man-made disasters, or other situations that could threaten the security of the facility and/or the general public. The plan should include communications, evacuation, and incident management procedures.

Access Management

Employing good access management techniques on infrastructure at the local level can help improve the efficiency and safety of the transportation and the freight system. Access management involves the proactive management of vehicular access points to land parcels adjacent to all manner of roadways. This presents an opportunity to link transportation and land use for the mutual benefit of freight operators, passenger vehicles and livability in the community. Access management includes the following techniques:

- Access Intersection and Driveway Spacing – Much of the congestion and delay on arterial highways results from traffic entering and exiting the highway from closely spaced driveways and intersections. Where possible, new commercial and industrial development should consider establishing a common driveway or access to a side street intersection with the arterial highway among several adjacent parcels. Increasing the distance between traffic signals improves the flow of traffic on major arterials, reduces congestion, and improves air quality and safety for heavily traveled corridors. It is important to ensure that parcels maintain reasonable access to the highway, and that access management concepts do not make access routes unreasonably long or complicated in such a way that the benefit is lost. The ideal spacing of intersections and driveways varies by functional class and speed limit on the highway. According to AASHTO, for a primary arterial with a speed limit of 45-55 miles per hour, the minimum suggested signalized intersection spacing is ½ mile. Unsignalized driveways (right-in-right-out configuration) should be spaced no less than 860 feet to avoid impacts on highway throughput capacity. (“Driveway and Street Intersection Spacing,” Transportation Research Board Circular 456, March 1996.)

- Safe Turning Lanes – dedicated left- and right-turn, indirect left-turns and U-turns, and roundabouts keep through-traffic flowing, and can provide safe pockets for cars and trucks to await opportunities to make turns. Roundabouts represent an opportunity to reduce an intersection with many conflict points or a severe crash history (T-bone crashes) to one that operates with fewer conflict points and less severe crashes (sideswipes) if they occur. Roundabouts with small radii can be difficult for trucks to navigate. The design of these features should take truck dimensions (especially turning radii) into account. Trucks should be able to make a turn without “sweeping” the tractor or trailer into adjacent traffic lanes.

- Right-of-Way Management – For the sake of preserving the capability to widen highways, expand, or reactivate rail infrastructure, existing rights-of-way should be maintained. When rights-of-way are encroached upon, the prospect of developing new transportation infrastructure is made far more difficult. (FHWA.)

The needs discussed above are some of the major items to be considered when planning the development of freight terminals, freight-dependent facilities such as stores and warehouses, on-site circulation and access routes, and general transportation infrastructure, such as bridges and highways. Other needs exist as well, but these highlight some of the major needs which can be positively impacted by public-sector policy and actions.

4.3 Tools and Actions to Address Freight Land Use Needs and Impacts

This section will review some of the key actions that can be taken at the local, regional, and state level to help meet the needs of freight stakeholders while also accounting for the needs of the community. Please refer back to Section 1.0 for further information on the role of various levels of government in the transportation planning process. With respect to land use, local governments are, for the most part, responsible for making land use decisions in response to private-sector development actions. Zoning requirements are established by the local government. Regional planning commissions help establish consensus-based regional visions for land use patterns. State agencies such as environmental regulatory and resource agencies perform permitting roles for specific developments, but generally have limited land use planning responsibilities.

Local Planning Actions

Local governments are responsible for comprehensive plans and zoning ordinances which can have a substantial impact on the effectiveness of freight movements at the site level and on the transportation infrastructure in general. In addition, local planning departments also can meet freight needs through additional freight stakeholder involvement and documents which clarify process and open communication between the groups. When reviewing the key freight needs discussed in Section 5.1, the following actions can be implemented at the local level to address key freight needs:

- Traffic access and impact studies gather and analyze information that will help determine the need for any improvements to interior, adjacent, and nearby road systems. New development sites can impact the surrounding roadway system by adding to existing traffic volumes or altering traffic patterns. In addition to designing appropriate access for proposed developments, planners and developers should strive to maintain a satisfactory level of transportation service and safety for all roadway users. Many municipalities or local planning agencies require a traffic access and impact study, which includes a trip generation estimate, prior to approving changes to zoning or proposed developments. In some instances, developers may be responsible for mitigating impacts to the adjacent transportation facility to meet the needs of the changed land use.

- Perform site planning reviews to make sure that new developments meet freight needs set forth by the community. For example, the Anchorage, Alaska MPO (highlighted as a case study in Section 4.3) has a committee of freight stakeholders who assist in site plan review and offer recommendations to better accommodate deliveries/freight. This type of review by an outside committee allows in-progress site plans to be checked to make sure that freight needs are met and that freight has the least possible negative impact on the community.

- Analyze truck routes through the municipality to ensure that key freight-dependent businesses are located near these truck routes and that the operational equipment, roadway maintenance and infrastructure along the truck route support large truck movement. For example, it is necessary to ensure that roads are in good condition and that bridges are high enough to accommodate both local and regional freight traffic moving through the area.

- Review the comprehensive plan to ensure that adequate land is set aside for industrial uses and potentially create a land use type which differentiates freight and intermodal uses from other industrial and commercial uses. Also review the comprehensive plan to ensure that current road design standards allow trucks to move efficiently through the municipality and to key loading and unloading areas.

- Enforce loading zone and parking restrictions in front of busy freight loading and unloading areas. Failure to do so will make loading and unloading in busy areas difficult for freight carriers and disrupt traffic.

- Involve private-sector freight stakeholders in developing site design standards to gather their input on how to best improve design standards and plans to ensure freight efficiency.

- Develop freight stakeholder committees that allow freight stakeholders to voice their concerns regarding land use policies and other infrastructure which impact the efficiency of freight movements.

- Integrate access management principles into the design of the local transportation infrastructure.

- Provide guidance to developers and others regarding expected regulations and highlight key items that they should be aware of and follow when developing a parcel of land. The guidance should include providing an inventory of appropriate developable or redevelopable industrial sites, information regarding available local tax incentives or financing mechanisms, and assistance interpreting and navigating through local permitting processes. In many cases, a municipality’s economic development officer also may serve as a liaison to state and Federal regulatory and permitting agencies. (NCFRP 23 Preliminary Draft Report.)

- Develop toolkits for industrial developers, including zoning requirements, permitting processes, key steps to complete the permitting process, and contacts at the planning/zoning offices. This will clearly define the process up front and open the lines of communication between public sector and developers up front.

- Use overlay zones with form-based or performance-based criteria to accommodate the needs of freight, or of particular industry types, while ensuring sensitivity to surrounding land uses. Overlay zones, can specify requirements for setbacks, parking, driveway spacing, and a variety of other factors, and require that development conform to the underlying zone. In this capacity, overlay zones offer zoning authorities an opportunity to maintain consistency with the zoning map, while having the flexibility to apply special circumstances in areas where warranted.

- Work with railroads and the Federal Railroad Administration to establish “quiet zones.” Quiet zones are areas in which trains can pass through at-grade intersection crossings without blowing their whistle, provided there are specific safety precautions taken to protect motorists and pedestrians crossing the rail right-of-way.

- Work with port planners to address “outside the gate” impacts. As domestic and international waterborne cargoes continue to land at port facilities throughout the country, communities that host port terminals should be engaged with terminal owners, operators, whether they be public or private entities, to address impacts of truck and rail traffic that are going “out the gate” onto the local transportation system. Developing suggested routing schemes to desirable intermodal connectors that avoid local neighborhood streets, optimizing signal timings, encouraging use of rail, and consideration of around-the-clock gate operations can help alleviate some of the impacts on the local transportation system. These strategies will have to be weighed against any noise, light, and air quality impacts that around-the-clock operation may have on adjacent properties. (NCHRP Synthesis 320 suggests that port operations can be limited to daytime hours (when most residents are away from home), though such a schedule could lead to adverse impacts on the transportation network, as daytime hours are when traffic volumes are highest. Potential operating schedules should be investigated and negotiated based upon considerations of both factors – effects on local residents and the transportation system – to determine the most desirable and least detrimental operating scheme.)

Regional Planning Actions

Regional governments, while generally not working on specific site design and land use issues, can have a role in helping regions and municipalities meet freight needs. The following are actions that MPOs and other regional government agencies can take to help meet freight and community needs:

- Lead regional visioning and goods movement studies to help lay out a bigger picture which local governments in the region can turn to in order to incorporate freight concerns when developing their plans and regulations.

- Create regional freight plans to help define key freight mobility goals and land use priorities in terms of freight.

- Create model land development ordinances and best practices for use by local governments when creating plans, ordinances, and other regulations that may impact freight.

- Create corridor or subarea plans to address congestion or safety issues on certain highway and rail freight corridors, regions, and/or major intermodal facilities that experience high traffic and crash volumes.

- Consider freight issues in development of metropolitan transportation plans and corridor studies. Freight is recognized among the planning factors that guide the metropolitan transportation planning process.

- Work with rail, air, and waterborne freight planners to ensure that the region’s ports, airports, and rail intermodal terminals are capable of handling current and future volumes of traffic safely and efficiently without significant adverse impacts on host communities or the region’s transportation system. Attributes such as transportation network capacity and utilization, terminal capacity and operating characteristics, truck stop and parking availability on a corridor or regional level should be examined.

State Planning Actions

State governments can help address freight needs in some of the same ways that regional governments can: by providing a vision for planning, by developing freight plans (statewide), and by providing model land development ordinance and best practices. Some states, including Florida and Oregon also have a limited active role in ensuring consistency among local land use plans relative to neighboring communities or state planning guidelines.

- Consider freight issues in the development of the statewide long-range transportation plan. Work with stakeholders across all modes to take inventory of the state’s transportation assets, including networks and nodes (terminals and other activity centers), identify needs, and develop a state policy on developing and maintaining freight infrastructure in the state.

- Include criteria in project selection processes that consider freight mobility as a criterion for project selection. For example, the Oregon Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) requires considering of freight mobility in the process of selecting projects.

- Design state highways, interchanges, and other freight infrastructure in such a way as to take freight needs into account and maintain mobility and safety.

- Create corridor plans or subregional plans to address congestion or safety issues on freight corridors and/or major intermodal facilities that experience high traffic and crash volumes.

- Work with municipalities or other local zoning authorities to ensure consistency with state planning goals and consistency among local land use plans to minimize conflicts between adjacent land uses in separate local jurisdictions.

Private-Sector Freight Stakeholder Actions

While the public sector can do many of the items listed above to meet freight needs, private-sector leaders, and stakeholders also need to take part in the planning process in order to make their needs heard. Several key actions that private-sector stakeholders should take to help meet freight needs:

- Participate in committees and the development of freight plans designed to improve freight operations in cities and states. Participation by private-sector stakeholders, including representatives from key regional businesses or industry groups, helps make sure that private-sector needs are considered. These committees may be organized by the MPO or local government agency.

- Offer opportunities for public-sector officials to learn about business and operations. This can come through presentations or by offering public-sector officials a site visit or a tour of the facility. Allowing public-sector officials to understand industry operations and to see the needs first-hand will help improve their understanding of the requirements that are to be addressed in plans and ordinances.

- Participate in and comment on metropolitan transportation plans, Long-Range Transportation Plans, corridor studies, comprehensive plans and other freight-related documents to make sure that private-sector comments are heard during the planning process. Public participation and consultation are key elements of the planning process.

Overall, it is important for both public-sector officials at all levels of government and private-sector representatives, such as chambers of commerce, rail and trucking associations, private rail or marine terminal operators, major shippers and receivers in the local area or region, and supply chain managers, to be engaged with one another and to understand each other’s viewpoints. This will help lead to plans and visions that both support livable communities and address freight needs.

4.4 Putting It All Together

The following case studies provide examples of collaborative efforts involving numerous levels of government, public-sector entities, and the private sector freight community. In each case, stakeholders were able to successfully implement projects that account for the needs of freight while preserving environmental and community sustainability. Each case study is presented according to the following outline:

- Issue Background – insight into the root and causes of the issue addressed by the case study plan or initiative.

- Approach and Resolution – a summary explanation of the procedure, findings and recommendations each case study plan or initiative identified.

- Critical Success Factors – key points or “takeaways” that may offer useful insight to planners and government agencies in other jurisdictions.

Case Study: Anchorage Metropolitan Area Transportation Solutions (AMATS) Private-Sector Involvement Strategies

Issue Background

Anchorage Metropolitan Area Transportation Solutions (AMATS) is the MPO for the City of Anchorage, Alaska. In addition to serving as the MPO, AMATS also is a municipal agency with zoning and land use authority. AMATS recognized that poorly planned industrial and retail sites did not account for the needs of freight, including provisions for adequate space for truck deliveries and circulation. The agency also recognized that government officials needed to better understand freight needs and incorporate them into the planning and site plan review processes.

Approach and Resolution

AMATS addressed these issues by engaging private-sector stakeholders. AMATS established a Freight Advisory Committee (FAC) to offer feedback on and enrich planning activities by providing the private-sector freight industry perspective, and to identify freight-related transportation and land use issues. AMATS also encourages FAC members to review and provide comments on-site plans for industrial and retail land uses. The FAC members offer advice on issues that affect the safety and efficiency of freight movements into, out of, and within a proposed facility, including space requirements, turning radii, parking lot configurations, and landscaping that could create unsafe blind corners. Although the Municipality of Anchorage does not pin all site plan review requirements on freight needs, they appreciate the FACs involvement and advice, and have on several occasions requested that developers of industrial and commercial properties make changes to their site plans to improve truck access and safety accordingly. In one example, the Municipality, based upon FAC input, asked the developer of a retail property to reduce the amount landscaping which was intended to hide loading bays. While the shrubs and trees screened loading bays from customers’ view, they also created a potentially dangerous blind spot and conflict between trucks entering and exiting the loading bays, and passenger vehicles traveling in the adjacent parking lot driveways. Upon hearing this concern, the developer made appropriate modifications to the site plan.

Through coordination with the FAC, AMATS has developed a collaborative relationship with private stakeholders. One FAC member invited local and state transportation planning staff to participate in a virtual reality simulation exercise. The exercise gave planners an opportunity to experience the sensation of driving a tractor-trailer through city streets and facility parking lots and loading zones. Through this exercise, public officials were able to better understand freight operations and transportation and land use requirements.

Critical Success Factors

- Engage freight stakeholders. AMATS has been able to develop a mutually rewarding collaborative relationship with freight stakeholders in Anchorage. The agency learned that getting the private-sector involved early in the planning process can help to improve transportation plans and site plans.

- Educate agency staff. The FAC has helped agency staff acquire a better understanding of freight issues through participation in meetings and by allowing staff to experience freight operations. Having staff who are educated in freight needs helps to ensure that those issues are addressed in transportation plans, project development, and site plans.

- Demonstrate progress. An important part of maintaining a relationship with private stakeholders is to ensure that their needs and issues are integrated into the creation, evaluation, and prioritization of strategies. If the private-sector stakeholders feel that their participation does not result in change, they may lose faith and interest in the participation program. By incorporating FAC ideas into the planning and project development processes, and by implementing projects, stakeholders could see that their input was valued and resulting in improvements.

Case Study: New York Metropolitan Transportation Council (NYMTC) Freight Villages Study

Issue Background

The New York Metropolitan Transportation Council (NYMTC) is the MPO for a 10-county portion of the New York City metropolitan area within New York State. Although the New York City region is a place where residents rely on transit services such as trains and subways for commuting and intercity trips, there are few alternatives to trucks and highways for freight shipments. Because the region consists of many islands and waterways, freight relies upon the region’s highway bridges and tunnels to reach terminals, distribution centers, and customers located throughout the region and beyond. Freight activity contributes to chronic and severe congestion on the limited number of bridges connecting the region. The NYMTC region also is a mature region, with little land available for new freight land uses. Freight land uses have sprouted throughout neighboring regions in New Jersey and Pennsylvania resulting in longer movements and few opportunities to attract new economic activity to the NYMTC region.

Approach and Resolution

The 2004 NYMTC Regional Freight Plan recommended a feasibility study of freight villages in the region as a means to consolidate supply chain functions into several activity centers served by multiple modes. This strategy, in theory, would reduce truck VMT, achieve redundancy and mode balance through multimodalism, and introduce new freight activities and economic development to parts of the region. The Freight Villages Study, (under development in 2011), has taken the following work steps:

- Literature review to uncover freight village types and applications throughout the world, and to identify the features of a typical freight village;

- Through input from industrial developers, third-party logistics firms, and transportation service providers, the project developed a list of site evaluation criteria and weighted evaluation metrics pertinent to the NYMTC region;

- Selection of six candidate sites and an evaluation of those sites relative to freight village features and NYMTC goals; and

- Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) analysis of the six sites to determine the potential for development of each.

The site analysis was conducted by applying scores to each of the sites using four evaluation criteria areas:

- Site suitability characteristics such as total and developable acreage, topography, potential for further expansion, utilities infrastructure, environmental characteristics, and security; existing facilities and activities that could be incorporated into the freight village activities;

- Access and transportation characteristics, including road, rail, water and air access, and ease of commuting for employees;

- Property conditions characteristics such as property ownership and cost, land use and zoning, running covenants that may restrict use, neighboring land uses and conflicts, recurring costs, attitude of neighboring communities, and pressures from existing property users; and

- Location and interconnected business activities attributes, including centrality of the site in relation to important consuming areas, proximity to major retailers and logistics providers, location in relation to interstate and regional freight transshipment facilities, availability of local trucking and availability of a suitable local workforce.

The Freight Villages Study currently is finalizing the results of the site evaluations, and will make recommendations regarding how and where freight villages could be implemented in the NYMTC region.

Critical Success Factors

- MPO leadership role in freight and land use visioning. The Freight Villages Study represents a strategy by which an MPO can take a leadership role in visioning and planning for goods movement and related land uses. Through this study, the MPO and constituent agencies have achieved a better understanding of a potential alternative for freight land use and development that may help them reach their sustainability goals.

- Account for the needs of freight stakeholders. The Freight Villages Study evaluated potential applications of freight village development patterns while keeping in mind the needs of the freight industries that will be encouraged to operate in these environments. Working with the industrial developers, third-party logistics firms, motor carriers, and railroads, the study conducted an evaluation of potential sites to account for attributes that are important to these stakeholders: site configuration and design, transportation system access, workforce and trucking availability, and accessibility to other freight facilities. The study recognized that the freight needs and regional sustainability needs should be met in order for sites to be feasible for freight village development.

Case Study: CenterPoint Intermodal Center Elwood, Illinois

Issue Background

The CenterPoint Intermodal Center in Elwood, Illinois, is a 2,500-acre intermodal facility used for the transfer, distribution, and warehousing of consumer materials and goods. Located about 50 miles southwest of Chicago, the site is a brownfield redevelopment project that includes a 775-acre intermodal transfer facility, as well as 8 million square feet of warehouse and distributions space. (Source.) The project included a wide range of public and private participation, in both the planning stages and to provide the roughly $1 billion in public and private financing. Now nearing completion (in 2011), the project is one that highlights the benefits of freight movement while minimizing the impacts to communities and the natural environment.

Approach and Resolution

Many existing truck-rail intermodal centers are located in or close to urban areas. Over time, growing regional populations will often begin to encroach on the facilities, converting land that was once vacant to higher-value residential and commercial uses. This can lead to capacity constraints of the intermodal facility, as well as growing freight and land use conflicts, including congestion, noise, and safety concerns. The Chicago area illustrates some of these concerns. It is one of the major freight hubs in the United States, and also one of the most congested. As freight volumes and the local population have grown, conflicts (such as congestion) have inevitably arisen. By some estimates, railed freight can take one day to reach Chicago from the West Coast ports, and can then take another entire day to move through Chicago. (Jack Lanigan, Sr., John Zumerchik, Jean-Paul Rodrequez, Randall Guensler, and Michael O. Rodgers, “Shared Intermodal Terminals and Potential for Improving Efficiency of Rail-Rail Interchange,” Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting, 2007, Paper #07-2563.)

The goal of this project is to increase the speed and capacity of freight. However, project proponents decided, early on, to achieve these goals in a manner that benefitted local communities and the environment. Several factors illustrate this approach:

- Choice of a brownfield redevelopment site. The site itself was the Joliet Arsenal, an abandoned plant located strategically on the Union Pacific (UP) and Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) mainlines and Interstates I-80 and I-55. However, the site also is a brownfield, and this project provided cleanup and remediation of an otherwise unused brownfield property.

- Choice of a site with adequate buffers to protect from encroaching land uses. As shown in Figure 4.4 below, the site is well-buffered from conflicting land uses. The buffers themselves are likely permanent entities, and include the Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery, and the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie restoration project.

- Shared costs and shared benefits. Multiple partners, including CenterPoint, the railroads, the Illinois DOT, the Illinois Department of Commerce and Community Affairs (DCCA), are taking part in financing the project. This partnership is possible because the benefits to multiple stakeholders have been documented. For example, the railroads will benefit from capacity improvements and freight efficiency enhancements, while local governments will benefit from thousands of new jobs and millions of dollars in tax revenues.

Critical Success Factors

- Inclusion of multiple levels of government, public agencies, and private industry. During the planning phases, the project brought together “virtually all levels of governments, more than a dozen public agencies, and private industry.” (Michael M. Mullen, “CenterPoint Intermodal Center,” Economic Development Journal, April 2005, p. 2.) In fact, CenterPoint estimates that it dealt with 50 (Michael Brick, “Village Says, ‘Yes, in My Backyard,’ to Rail Center,” July 17, 2002. The New York Times.) governmental entities throughout the planning and development cycle. Though time consuming, the inclusion of all these entities meant that issues were resolved as they arose, without ever resulting in loss of partners or build-up of animosity.

- Highlighting the positive benefits of the development to the public. The site is located in an area of high unemployment. Therefore, using the site as an engine of local economic development was critically important. It is estimated that this site will employ over 8,000 people once completed. (Source.)

- Shared resources and shared benefits. The project was designed and is being implemented with shared public private financing. Therefore, there was “give and take” throughout the process so that all parties felt that they were receiving benefits. For example, though the Illinois DOT and the Illinois Department of Commerce and Community Affairs (DCCA) is funding the road improvements, CenterPoint is donating 60 acres of land to a wetlands conservation project and another 83 acres to the U.S. Forest Service. These types of arrangements have helped to prevent a buildup of public animosity towards a large-scale industrial development.

Case Study: The Kansas City Cross-Town Improvement Project (C-TIP)

Issue Background

The Cross-Town Improvement Project (C-TIP) was first conceived in the fall of 2004 and has since grown in both size and stature. The C-TIP is a technological solution to the problems arising from transferring goods from rail to truck in metropolitan regions. Whether it is truck-to-rail transfers near ports, or rail to truck to rail transfer near rail interchanges, the inefficiency of cross-town “rubber tire” interchanges can have negative impacts, including: congestion, loss of efficiency in the transportation network, safety concerns, energy consumption concerns, and impacts to the local environment. (“Cross Town Improvement Project” given by Randy Butler, U.S. Department of Transportation. The “Talking Freight” seminar, November 17, 2010.) Kansas City was chosen as a pilot study location because it is the second largest rail hub in the U.S. (after Chicago), yet is smaller and less expensive to implement (compared to a pilot study in Chicago).

The C-TIP concept is an intermodal move database that will coordinate cross-town traffic to reduce empty moves between terminals, track intermodal assets, and distribute information to truckers wirelessly.

Approach and Resolution

Several key steps highlight the approach that was taken to this project.

Work with stakeholders to define a problem. The approach to the project first focused on defining the problems that were to be solved. This was accomplished through discussions with public and private freight stakeholders. These discussions revealed several growing problems in the Kansas City region that are caused by cross-town drayage, such as:

- Growing freight volumes;

- Increasing port-related traffic;

- Growing congestion at key locations where “cross-towns” occur;

- Air quality degradation from an aging fleet and unnecessary truck miles traveled within urban areas; and

- Inefficiency of the port-related truck fleet.

Once the issues had been discussed among multiple public- and private-sector stakeholders, it was determined that the root cause of the issue was a lack of communication between the many parties involved in cross-town drayage.

Define a solution that is implementable. When completed, C-TIP will help to mitigate the number of trucks involved with cross-town “rubber tire” interchanges. This, in turn, will help to improve the efficiency of the region’s transportation network, as well as ensure the safety of its citizens. These benefits are illustrated in Figure 4.4 below.

Figure 4.4 The C-TIP Public Private Partnership Goal

Source: U.S. DOTs Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

Critical Success Factors

- Inclusion of multiple levels of government, public agencies, and private industry. The key players throughout the pilot study are the U.S. DOT – FHWA, multiple Class I railroads (BNSF, UP, and Kansas City Southern (KCS)), trucking companies, state governments, Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPO), economic development groups, and traffic management organizations.

- Identification of a clear vision and goals. The project began with a clear identification of the problem at hand (i.e., too many unproductive moves in a congested urban area), and then worked with stakeholders to envision an innovative, yet implementable, solution. The goal statement for C-TIP is now: “To develop and deploy an information sharing/transfer capability that enables the coordination of moves between parties to maximize loaded moves and minimize unproductive moves.”

4.5 Conclusion

As highlighted in these case studies, as well as throughout the rest of the handbook, land use patterns and land use decision-making can impact freight movements and industries in many ways – including impacts on regional truck vehicle miles traveled (VMT), intermodal accessibility and safety, land consumption, and access to jobs. If freight planning and land-use decision-making activities are well-integrated, both the public and private sectors may benefit through reduced congestion, improved air quality, enhanced community livability, increased industrial-related jobs and activity; and improved operational efficiency, reduced transportation costs, and greater access to facilities and markets.

However, arriving at decisions that maximize the benefits of freight, while minimizing the impacts, can be very complex. On the public side, industrial development goals are too often overshadowed by other community goals, including smart growth strategies that seek to redevelop industrial lands into residential and commercial uses, and efforts to push freight facilities to the regional fringe. From the private-sector side, the slower pace and many stages of land use planning can seem complex, frustrating, and not inclusive to private-sector participation. As a result, many agencies are struggling to understand how land use issues impact freight movements (and vice versa), the types of stakeholders that should be involved in land use and freight planning activities, and the tools, techniques, and strategies used by agencies across the country to deal with these issues.

This handbook has provided some grounding, knowledge, and examples for public- and private-sector entities that are interested in understanding freight and land use integration issues. Topics highlighted within this handbook include:

- Background on freight and land use issues, including the key concepts and trends in land use and freight transportation, as well as the linkage between freight, land use, and economic development.

- Key steps and products of the transportation and land use planning processes and the linkages between those processes, including a discussion about the relevant public and private stakeholders, their roles and needs, the key freight and land use issues and trends affecting decision-making now and in the future.

- Discussion of freight as a good neighbor, including a range of strategies and tools that have been used successfully to ensure that freight land uses have a positive relationship with surrounding land uses, and have been used successfully to integrate freight uses into the community fabric.

- Discussion of sustainability, including the potential ramifications of poor land use planning and policies on an economic development, environmental sustainability, and social equity and justice.

- Discussion of how freight and land use decisions can meet current freight demands, while encouraging desirable growth patterns in the future, including guidance about how to avoid or mitigate the unintended consequences of land use decisions on freight movements.

- Discussion of the impacts and needs of freight, including the land use needs of freight-generating industries and facilities, including access, on-site circulation, dimensional requirements for trucks, adequate truck parking and loading areas, and security provisions.

- Discussion of transportation and land use planning processes, including strategies and action steps aimed at engaging private-sector stakeholders and incorporating freight needs into the planning processes.

Together, the topics covered in this handbook will introduce some of the main players, policies, programs and strategies that form the basis of knowledge for integrating freight into the land use planning process. By providing a broad swath of viewpoints, the handbook should appeal to public- and private-sector freight stakeholders from all sides of the issue – including industrial site developers, land use practitioners, local government officials, members of the public – or anyone else.

Though this handbook is comprehensive, it is a static document. Readers should remember that the freight industry is a rapidly and ever-changing industry, reflective of economic and demographic shifts as well as global supply chain developments. Public and private stakeholders, alike, need to continue to work towards understanding the regions within which they operate. States and regions are constantly identifying ways to increase their ability to compete regionally, nationally and globally. Private-sector companies are constantly trying to streamline and economize their operations, and develop innovative solutions to existing problems. This handbook provides a good understanding of the issues, needs, opportunities, and strategies that will serve as a starting point to better integrate freight and land use in an ongoing and permanent manner.

You will need the Adobe Reader to view the PDFs on this page.

previous | next