Advancing Congestion Pricing in the Metropolitan Transportation Planning Process: Four Case Studies

1.0 Summary and Findings

1.1 Background and Purpose

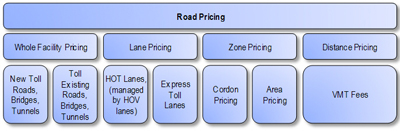

Road pricing is being considered by more and more regions as a reaction to the dual challenges of declining revenues and increasing congestion. Road pricing is more than simply tolling a new highway with flat tolls, it involves charging a fee to use a lane, road, area, or regional network for purposes of generating revenue, managing traffic congestion, or both (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Types of Road Pricing

Note: Any of these can use "congestion pricing" or "variable pricing" to achieve policy objectives.

Road pricing is called “congestion pricing” when prices are tailored to manage congestion by using a fixed time-of-day schedule or a dynamic algorithm based on congestion levels. In any case, some forms of road pricing can generate revenues in support of roads and/or auto alternatives, and can help achieve environmental objectives, such as reducing air pollution or greenhouse gas emissions.

Road pricing in the United States is new and not well understood by the general public and elected officials. The most common form of road pricing in the United States has been high-occupancy toll (HOT) lanes, where high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes are opened to use by vehicles with lower occupancy for a fee, or express toll lanes where new lanes are built adjacent to existing freeways and use of these new lanes is subject to a toll.

Road pricing experiments in Europe and Asia have involved zone pricing, where drivers are charged a fee to enter into and/or drive within a specified high-congestion location. Zone pricing may or may not have a time-of-day component.

As states and regions consider ways to address declining revenues from the motor fuel tax, the concept of distance pricing – charging drivers for each mile they drive on the highway system – is being discussed more and more. This is often referred to as vehicle miles traveled (VMT) fees, or mileage-based user fees. These are typically seen as a revenue mechanism, but could also incorporate a congestion-pricing component.

What Is Congestion Pricing?

Congestion pricing – sometimes called value pricing – is a way of harnessing the power of the market to reduce the waste associated with traffic congestion. Congestion pricing works by shifting purely discretionary rush hour highway travel to other transportation modes or to off-peak periods, taking advantage of the fact that the majority of rush hour drivers on a typical urban highway are not commuters. By removing a fraction (even as small as five percent) of the vehicles from a congested roadway, pricing enables the system to flow much more efficiently, allowing more cars to move through the same physical space. Similar variable charges have been successfully utilized in other industries – for example, airline tickets, cell phone rates, and electricity rates. There is a consensus among economists that congestion pricing represents the single most viable and sustainable approach to reducing traffic congestion.

Source: Congestion Pricing, A Primer, FHWA, 2006.

Road pricing often has come about separate from the traditional metropolitan planning process through pilot projects and demonstrations. As pricing demonstration projects have shown road pricing to be an effective tool, there is a growing need to incorporate road pricing into long-range plans. This study examined how road pricing was incorporated into long-range planning at four metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) to provide examples that could support other regions seeking to do the same.

1.2 The Case Study Regions

The four case study regions were selected by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) based on a previous study, A Domestic Scan of Congestion Pricing and Managed Lanes (A Domestic Scan of Congestion Pricing and Managed Lanes, prepared for the Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation by DKS Associates, with PBSJ and Jack Faucett Associates, February 2009). The case studies represent places where road pricing was successfully included in long-range plans – examples from places where road pricing has not been included in long-range plans are not covered. The key themes used to guide the case studies were based upon findings from the initial literature review provided in Appendix B. The team reviewed the relevant studies and planning documents from each region, and then conducted interviews with staff from the responsible regional planning organizations. The Interview Guide is in Appendix C.

Dallas/Fort Worth Region, Texas

The Dallas/Fort Worth region has had road pricing in the form of toll roads for decades. The region has aggressively pursued innovative partnerships, both public and private, to advance roadway projects through pricing. Examples include recent public-private partnerships to build the North Tarrant Express (IH 35W/IH 820/SH 183) and LBJ Freeway (IH 635) managed lanes. A high-growth area, the region is still planning to build new lane-miles of highway, and has a policy to consider any new capacity as tolled capacity. The result was a long-range plan that includes numerous new toll roads and new tolled managed lanes (where HOV and transit are free), and new priced express lanes (where all vehicles pay). Beyond the project lists, there are explicit policies that govern issues such as rate setting and use of revenues.

Puget Sound Region, Washington

The last tolls came off a bridge in the Puget Sound region of Washington State in 1979, but when a new bridge was needed across the Tacoma Narrows, it was built as a toll bridge. Though it is a high-growth area, there are few new highways planned in the region. Realizing that traffic demand will far outstrip the capacity of available and planned facilities, the region has been serious about how road pricing could be used to manage transportation demand while at the same time providing a revenue source for high-priority improvements. The SR 167 HOV lane was converted to a HOT lane several years ago and several other HOT lane projects are under consideration. With the SR 520 bridge across Lake Washington in need of replacement due to seismic concerns, a consortium of agencies is advancing a project to toll the existing crossing using congestion-pricing techniques and using the revenue to partially pay for the construction costs of a new bridge. As the region started to update its long-range plan, some level of road pricing was included in every plan alternative, and pricing became a key component of the plan.

Minneapolis/St. Paul Region, Minnesota

The Twin Cities built two HOT lane projects over the last few years: I‑394 and I‑35W. These projects were the result of more than a decade of proposals to address congestion in these corridors. On I‑394, an underutilized HOV lane was converted to a HOT lane. On I‑35W, existing shoulders that already had allowed bus use were converted to travel lanes, and the existing inside lane was converted to a HOT lane. Looking beyond these individual projects, the region has been trying to address how to consider new opportunities for HOT lanes when it plans new expansion projects. Like Seattle, new highways are not being planned, but expansions of existing highways might be accommodated as HOT lanes.

San Francisco Bay Area, California

Several counties and congestion management agencies have been studying new HOT lanes as a way to improve the efficiency of existing highways. The Alameda County Congestion Management Agency is moving forward with HOT lanes on I‑680 and I‑580, and has studied HOT lanes in other corridors. Santa Clara County did a countywide assessment of HOT lanes and is moving forward with projects on the SR 237/I‑880 Connector, and Route 85 and U.S. 101. Marin and Solano counties also have explored HOT lanes. Concerned about a variety of projects following a variety of standards, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission carried out several studies aimed to bring consistency to the development of these lanes. An extensive network of priced lanes became a centerpiece of the region’s transportation plan update, including design standards and rules for use of revenue. In addition, congestion pricing of the Bay Bridge was recently implemented, and the City and County of San Francisco has been studying cordon/area pricing.

1.3 Lessons Learned

Our scan of these four regions where road pricing was successfully incorporated into long-range transportation plans revealed that every region is unique. Each region brings a history of attitudes, jurisdictional negotiations, and politics that influences how pricing is perceived.

Regional Road Pricing Policy Grew from Individual Projects

None of the regions began with a broad concept of road pricing as an integral part of their long-range transportation vision. Rather, in all regions, individual project proposals introduced the metropolitan area to pricing.

In the Puget Sound region, tolling the Tacoma Narrows Bridge helped bring attention and support to tolling for financial support. Later, the Route 167 HOT lane project in another part of the region introduced the idea of congestion pricing.

The Dallas/Fort Worth region had a long history of toll roads. The region’s expected high-growth rate was expected to create intense traffic demands. With extensive highway needs and limited revenues, Texas had a policy to consider pricing for all new highway projects around the State.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, early proposals to congestion-price the Bay Bridge were defeated, but after the success of HOT lanes around the United States and with the encouragement of the FHWA’s Value Pricing Pilot Program (VPPP), the counties in the Bay Area started planning HOT lanes. Variable pricing of the Bay Bridge was recently implemented, aided by the need to raise tolls to pay for a vital seismic retrofit.

Soon after the success of the SR 91 and I‑15 managed lanes projects in southern California, the Minnesota Department of Transportation (Mn/DOT) tried to convert an underutilized HOV lane on I‑394 to a HOT lane. Early efforts to introduce pricing in Minnesota were unsuccessful, but persistence paid off as the I‑394 HOT lane came to fruition almost 10 years later and a second HOT lane has recently opened on I‑35W, enabled by the success and acceptance of I‑394.

Once individual projects were committed or underway and gaining favorable response, regional and state governments adopted them into long-range plans and developed supportive policies. The push to include policies on pricing in long-range plans grew out of a need for consistency in the application of pricing around a region and ways to allocate revenues. As regions looked beyond their initial pricing projects, consistency of development and revenue allocation policy became important. Also of concern were consistent design and technology policies.

The Dallas/Fort Worth region developed policies that defined toll rates and how revenues would be used, among others. The Puget Sound region went through years of study both at the state level and in the region to define how or whether road pricing would form an important part of the transportation landscape. In the end, the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) came up with a 30-year vision to allow pricing to evolve as technology allowed, with pricing integral to support broad goals for the region both for revenue and as a way to manage demand.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, individual counties and congestion management agencies were proceeding with development of HOT lane projects. In response, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) took on a study of a HOT lane network and a long-term vision for pricing that defined how road pricing revenues would be spent. The Twin Cities experience was more understated. Though Mn/DOT and the Metropolitan Council studied systems of HOT lanes, these agencies were not in a position to move forward boldly. The Metropolitan Council’s long-range plan reflects an understanding that there is more pricing in the future in conjunction with transit expansion, but is not specific about how such pricing would be accomplished.

Developing the Right Tools for the Job

All regions struggle with developing the right tools to provide the analysis to support difficult public policy decisions surrounding pricing. Basic four-step travel demand models are not well suited to the complex societal changes that extensive road pricing can bring about. The different visions of road pricing in each region has shaped how the emphasis on the tools that were developed.

In the Twin Cities, the main emphasis was on HOT lanes, which give travelers a choice of one lane or another in one corridor. The questions revolved around whether these lanes would improve speeds and throughput in the corridor. From a regional perspective, the main question to be answered was “how many people would choose to use the managed lane at what price.” This resulted in relatively simple modifications to the traffic assignment routines that did not try to account for more complicated changes in travel patterns such as changes to trip distribution patterns, trip-making volume, or housing/job location decisions.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, MTC is moving from a trip- to activity-based model to give more precision to pricing analysis. The model also has been modified to do better mode choice prediction since mode shift is an important impact of pricing. Perhaps most important, MTC planners and analysts use latest travel survey data from The Bay Area Transportation Survey to get accurate elasticities for modeling. MTC also uses benefit/cost analysis to explain the benefits of pricing and equity assessments that explain impacts and benefits on different income groups.

In the Dallas/Fort Worth region, the emphasis was on toll roads and HOT lanes, and thus the North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG) model development focused on assignment-path decisions rather than more extensive modeling of travel pattern changes. NCTCOG was concerned, however, about whether road pricing impacted poor people more than other parts of the population and developed techniques to understand which populations would be paying tolls. Moving forward, however, NCTCOG has plans to improve their analytical tools using before-and-after studies on the SH 161 toll road now under construction to capture eight different behavior changes, such as route, mode, destination, and housing location.

The Puget Sound region has the most extensive plans for pricing – with VMT fees in its long-range vision. As a result, the policy boards tasked with developing the long-range plan demanded better answers relating to changes in driver behavior as well as development patterns and economic impacts. PSRC spent several years developing new travel demand modeling and benefit/cost analysis techniques. The Traffic Choices study funded in part by the VPPP provided a wealth of data on travel behavior changes under priced conditions that found its way into the travel demand model. One byproduct of these sophisticated tools was the need to develop new approaches to communicate the findings to lay audiences.

Communication of Road Pricing Concepts Is a Challenge Everywhere

Communication of road pricing concepts and consensus-building can be difficult, especially when those concepts are unknown and untested. In the Dallas/Fort Worth region, road pricing is a logical outgrowth of toll road development that had been going on for decades. This incremental approach aided public and stakeholder acceptance. Engagement is continuous to maintain support and visibility for tolling and pricing.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, MTC endured failure of Bay Bridge pricing proposals over several years, but now has gained acceptance of a HOT network in its long-range plan and recently implemented time-of-day pricing on the Bay Bridge. The HOT lane network benefited from successful HOT lane projects in other parts of California, but the region’s acceptance of the HOT lane network also sprang from the idea of expediting development of the HOV network over and above what regular funding would allow, rather than congestion pricing per se. Despite the experience elsewhere, MTC works hard to explain how HOT lanes would work, how HOT lanes benefit transit users, and how the “Lexus lane” concept is misguided.

Both Mn/DOT and the Metropolitan Council in the Twin Cities have been undertaking public communications efforts surrounding road pricing (in particular HOT lanes) for 10 years in the aftermath of a failed HOT lane proposal. In particular, the Humphrey Institute of the University of Minnesota has been active (both locally and at the national level) in trying to understand people’s attitudes and crafting messages that address lingering concerns. Through engagement of influential decision-makers and a policy of “leaving no question unanswered” when it comes to the HOT lanes projects, Mn/DOT has finally brought about two successful HOT lane projects and, with the Council, continues to plan for more pricing in the future.

PSRC had the most extensive need for communication, because it was exploring the most extensive use of pricing in its plan. Pricing had been discussed for years in the region, including support by the Secretary of Transportation. A key element of the approach was to emphasize that pricing was one element of a larger plan. Recognizing early the challenges they would face, PSRC formed a Pricing Task Force that could get educated on the more complicated points of road pricing, and then carry that message back to their constituents. PSRC also had a well-respected champion that could speak to elected officials and gain their support.

Pricing Is One Element of a Cohesive Transportation Plan

All four regions found that making road pricing one element among many of a cohesive transportation plan was effective at gaining acceptance for the concepts. This meant integrating project lists, road pricing concepts, and decisions about how to handle potential revenue, showing that these pieces all worked together.

In the Puget Sound region, especially, pricing was a cornerstone of the plan, with the revenue to be generated by large-scale pricing of the existing highway system a key element of the financial plan as well as a key mechanism to move towards achieving greenhouse gas emission reduction goals. The same was true in the Dallas/Fort Worth region, where pricing, in the form of tolled highways and lanes was an important revenue source for highway expansion. In the San Francisco Bay Area, HOT lanes were a way to increase highway capacity through more effective use of existing and planned HOV lanes, and contribute a revenue source to accomplish that. In the Twin Cities region, HOT lanes were part of a mix of strategies, including bus-only shoulder lanes, priced dynamic shoulder lanes, and other elements of the long-range plan.