Traffic Incident Management Quick Clearance Laws:

A National Review of Best Practices

This publication may contain dated technical, contact, and link information.

Move Over Laws

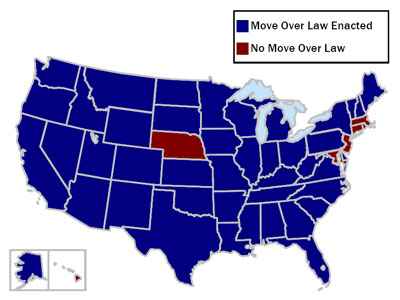

At the time of this investigation, all but seven States have enacted Move Over laws (see Figure 1). A Move Over law typically requires motorists to change lanes and/or slow down when approaching an authorized emergency vehicle that is parked or otherwise stopped on a roadway. Although these general requirements are consistent, State Move Over laws differ significantly in the specific provisions defining when drivers are obligated to take action and what action they are required to take.

FIGURE 1. States with Move Over Laws Currently Enacted

A review of the purpose and intent, model language, observed content trends and anomalies, and implementation challenges and resolutions for Move Over laws is provided below. As appropriate, excerpts from model law and State Move Over legislation are included.

Purpose and Intent

The proliferation of Move Over laws among U.S. States can largely be explained by the common interest in ensuring response personnel safety, and the concurrent targeted national public awareness campaigns.

As reported previously, an estimated 225 responders have been killed after being struck by vehicles along the highway since 2003 (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2008, Towing and Recovery Association of America 2008). ResponderSafety.com reports that two emergency responders per day, on average, are fatally or non-fatally struck by passing vehicles. A recent Ohio State Highway Patrol investigation (Law Enforcement Stops and Safety Subcommittee 2006) found that 55 percent of officer-involved, struck-by incidents involved serious injuries or fatalities and 60 percent occurred on high-speed, high volume interstate highways. Move Over laws may reduce both the frequency of responder struck-by incidents, as well as the severity of such incidents when they do occur by requiring drivers to provide a buffer area between responders and moving traffic and travel at reduced speeds.

While the primary intent is to ensure responder safety, Move Over laws may also serve to reduce the frequency and severity of secondary crashes involving approaching motorists and expedite the overall incident clearance process, reducing associated congestion and delay.

Since Move Over laws are relatively new, little documented evidence to date exists regarding the impact of such laws in enhancing responder safety or the effectiveness of associated public awareness campaigns in achieving compliance from the motoring public. Anecdotally, responders have expressed concern over the lack of Move Over law awareness among drivers and the subsequent ability of these laws to enhance responder safety and realize additional associated benefits.

Model Language

Move Over laws are commonly included as extensions to pre-existing laws directing a driver to slow and pull to the side of the road to allow emergency vehicles with warning devices activated to pass. These laws have been modified to include driver guidance when approaching and passing stationary emergency vehicles along the roadside.

Laws are only effective when enforceable. Citations based on early versions of Move Over laws were often dismissed or failed judicial review because of inadequate, ineffective wording in the State's legislation. In response to this shortcoming and as part of a broader effort to improve responder safety, the NCUTLO, working closely with the NHTSA and NCSL, published the Incident Responders' Safety Model Law. Model Move Over law language is included in Section 7 as follows:

Section 7. Road User Duties Approaching Incidents

- When in or approaching an incident, every driver shall maintain a speed no greater than is reasonable and prudent under the conditions, including actual and potential hazards then existing.

- When in or approaching an incident area, every driver shall obey the directions of any authorized official directing traffic and all applicable traffic control devices.

- Except for emergency vehicles in the incident area, when in or approaching an incident area every driver shall reduce speed and vacate any lane wholly or partially blocked.

- (d) If a violation of this section results in a serious injury or death to another person, in addition to any other penalty imposed by law, the violator's driver's license shall be suspended for a period of at least

(180) daysone year and not more than (25) years and the violator may be sentenced up to one year in jail.

Note the more recent changes in (d) that encourage more severe sanctions for Move Over law violators. Additional guidance for Section 7 defines an "incident" as "an emergency road user occurrence, a natural disaster, or a special event" and an "incident area" as "an area of highway where authorized officials impose a temporary traffic control zone in response to a road user incident, natural disaster, or special event."

Both the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) and the National Sheriffs' Association (NSA) have adopted resolutions in support of uniformity in Move Over laws.

Content Trends and Anomalies

Common to each of the Move Over laws enacted in each State is the general requirement of vehicles to change lanes and/or slow down when approaching stationary emergency vehicles. The specific provisions defined in each law, however, vary significantly among States despite recent efforts to encourage uniformity in Move Over laws. Distinctive provisions contained in Move Over laws relate to:

- the definition of an "emergency scene" at which drivers must take action;

- a driver's responsibility to change lanes when the adjacent lane is available and the maneuver can be performed safely;

- a driver's responsibility to slow down and control their vehicle to avoid collision; and

- State-mandated driver education initiatives and enforcement directives.

Specific examples of commonalities and differences in Move Over law provisions are furnished below. Note that the examples provided reflect a subset of existing Move Over laws. Much of the statutory language is consistent between States. Where differences do exist, individual examples were included to reflect a broader set of State laws. In the interest of brevity, few State laws are included in their entirety; and language not directly related to Quick Clearance operations is excluded. However, the legal citations are included for further follow-up by the reader.

Definition of an Emergency Scene

An emergency scene at which drivers are required to follow provisions of the Move Over law is most often described in terms of agencies present, or more specifically, the "authorized emergency vehicles" present. Most often, Move Over law provisions are applicable only when: (1) emergency vehicles (i.e., vehicles owned and operated by law enforcement, fire and rescue, and emergency medical service agencies); (2) emergency and towing/recovery vehicles; or (3) emergency, transportation maintenance, and towing/recovery vehicles are present. Oftentimes the applicability of Move Over law provisions is further qualified by the color and activation status of vehicle-mounted flashing lights and/or the performance of official duties. Consider the following examples.

State Move Over laws apply when the following vehicles are on-scene:

- emergency vehicles only (Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Delaware, Idaho, Louisiana, Maine, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wyoming);

Alabama §32-1-1.1. (3) Authorized Emergency Vehicle. Such fire department vehicles, police vehicles and ambulances as are publicly owned, and such other publicly or privately owned vehicles as are designated by the Director of Public Safety or the chief of police…

Minnesota §169.01. "Authorized emergency vehicle" means any of the following vehicles when equipped and identified according to law: (1) a vehicle of a fire department; (2) a publicly owned police vehicle or a privately owned vehicle used by a police officer…; (3) a vehicle of a licensed land emergency ambulance service, whether publicly or privately owned; (4) an emergency vehicle of a municipal department or a public service corporation…; (5) any volunteer rescue squad…; (6) a vehicle designated as an authorized emergency vehicle upon a finding by the commissioner of public safety… - emergency and towing/recovery vehicles (California, Colorado, Florida, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina);

Colorado §42-4-213. (6) "Authorized emergency vehicle" means such vehicles of the fire department, police vehicles, ambulances, and other special-purpose vehicles as are publicly owned and operated by or for a governmental agency to protect and preserve life and property…; said term also means the following…: (b) Privately owned tow trucks approved by the public utilities commission to respond to vehicle emergencies.

Florida §316.126. (1)(b) When an authorized emergency vehicle making use of any visual signals is parked or a wrecker displaying amber rotating or flashing lights is performing a recovery or loading on the roadside… - emergency, transportation maintenance, and towing/recovery vehicles (Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Tennessee, Utah, Wisconsin); and

Georgia §40-6-16. (a) …a stationary authorized emergency vehicle that is displaying flashing yellow, amber, white, red, or blue lights…(b) …a stationary towing or recovery vehicle or a stationary highway maintenance vehicle that is displaying flashing yellow, amber, or red lights…(Indiana §9-21-8-35 and Iowa §321.323A contain similar language).

- emergency, towing/recovery, and animal control vehicles (Alaska).

Alaska §28.35.185. (a) …a stationary emergency vehicle, fire vehicle, law enforcement vehicle, tow truck in the act of picking up a vehicle, or animal control vehicle being used to perform official duties, when the stationary vehicle is displaying flashing emergency lights…

South Carolina sect;56-5-1538. (A) An emergency scene is a location designated by the potential need to provide emergency medical care and is identified by emergency vehicles with flashing lights, rescue equipment, or emergency personnel on the scene. (I) For purposes of this section: (1) "Authorized emergency vehicle" means any ambulance, police, fire, rescue, recovery, or towing vehicle authorized by this State, county, or municipality to respond to a traffic incident. (2) "Emergency services personnel" means fire, police, or emergency medical services personnel (EMS) responding to an emergency incident.

Note that transportation maintenance personnel, towing/recovery operators, and service patrol operators are often not included under the purview of these laws despite the fact that they face the same level of danger in the roadway environment. In the interest of responder safety, Move Over laws should include this wider range of traffic incident management personnel.

Driver's Responsibility to Change Lanes

Move Over laws in select States (i.e., Mississippi, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota) do not require drivers to change lanes. In States that do, Move Over laws differ in terms of specificity regarding driver action. Some observed Move Over laws are somewhat vague in the actions required of the driver (i.e., use due care not to collide, provide as much space as practical, etc.) while other laws provide explicit direction (move to a non-adjacent lane, move to a lane farthest away from the emergency vehicle, etc.). Consider the following examples.

State Move Over laws require a driver to:

- use due care not to collide with stationary emergency vehicles (New York);

New York Pending Bill S02051A. Enacts the "Ambrose-Searles Move Over Act" which requires every operator of a motor vehicle to exercise due care to avoid colliding with an authorized emergency vehicle which is parked, stopped or standing on the shoulder or any portion of a highway…

- provide as much space as practical to (Utah), give a wide berth to (New Hampshire), and move as far away from (Montana) the authorized emergency vehicle;

Utah §41-6a-904. (2) The operator of a vehicle…shall: (b) provide as much space as practical to the stationary authorized emergency vehicle; and (c) if traveling in a lane adjacent to the stationary authorized emergency vehicle…make a lane change into a lane not adjacent to the authorized emergency vehicle…(3) The operator of a vehicle, upon approaching a stationary tow truck or highway maintenance…shall: (b) provide as much space as practical to the stationary tow truck or highway maintenance vehicle.

New Hampshire §265:37. …every driver…shall: IV. Give a wide berth, without endangering oncoming traffic, to public safety personnel, any persons in the roadway, and stationary vehicles displaying blue, red, or amber emergency or warning lights.

Montana §61-8-346. (3)…upon approaching a stationary authorized emergency vehicle or police vehicle that is displaying visible signals of flashing or rotating amber, blue, red, or green lights, the operator of the approaching vehicle shall: (a) reduce the vehicle's speed, proceed with caution, and, if possible considering safety and traffic conditions, move to a lane that is not adjacent to the lane in which the authorized emergency vehicle or police vehicle is located or move as far away from the authorized emergency vehicle or police vehicle as possible… - yield right-of-way by moving to a lane that is not adjacent to the authorized emergency vehicle (Alabama, California, Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia); and

Colorado §42-4-705(2). (b)…the driver of an approaching or passing vehicle shall proceed with due care and caution and yield the right-of-way by moving into a lane at least one moving lane apart from the stationary authorized emergency vehicle…

Minnesota §169.18.11. (b)…the driver of a vehicle shall safely move the vehicle so as to leave a full lane vacant between the driver and any lane in which the emergency vehicle is completely or partially parked or otherwise stopped…

North Dakota §39-10-26.2. …an approaching vehicle shall proceed with caution and yield the right of way by moving to a lane that is not adjacent to the authorized emergency vehicle… (Virginia §46.2-921.1 and West Virginia §17C-14-9a contain similar language).

South Carolina §56-5-1538. (G) A person driving a vehicle approaching a stationary authorized emergency vehicle…shall…(1) yield the right-of-way by making a lane change into a lane not adjacent to that of the authorized emergency vehicle…(Tennessee §55-8-132 contains similar language). - merge into the lane farthest from the emergency vehicle (Minnesota, Wyoming).

Minnesota §169.18.11. (a) When approaching and before passing an authorized emergency vehicle…the driver of a vehicle shall safely move the vehicle to the lane farthest away from the emergency vehicle…

Wyoming §31-5-224. (i) When driving on an interstate highway or other highway with two (2) or more lanes traveling in the direction of the emergency vehicle, shall merge into the lane farthest from the emergency vehicle, except when otherwise directed by a police officer…

Many of the lane change provisions described above include qualifying language under which the Move Over law provisions would not apply if:

- less than two lanes exist in each direction (Alaska, Indiana, Michigan, South Carolina, South Dakota, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin);

Michigan §257.653a. (1) (b) On any public roadway that does not have at least 2 adjacent lanes proceeding in the same direction as the stationary authorized emergency vehicle…

South Carolina §56-5-1538. (G) (1) …if on a highway having at least four lanes with not less than two lanes proceeding in the same direction as the approaching vehicle… - changing lanes would be "impossible or unsafe" (Alabama, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Missouri, Montana, Tennessee) or "unreasonable or unsafe" (Virginia);

Alabama §32-5A-58.1. (b) If changing lanes would be impossible or unsafe…(Illinois §625.5/11-907(2), Indiana §9-21-8-35(2), Kentucky §189.930(b), and Maine §2054-9.B contain similar language).

Virginia §46.2-921.1. (ii)…if changing lanes would be unreasonable or unsafe… - changing lanes would interfere with any vehicular traffic (North Carolina, Wisconsin);

North Carolina §20-157. (2)…if…the approaching vehicle may not change lanes safely and without interfering with any vehicular traffic (Wisconsin §346.072 contains similar language).

- safety, road, weather, and/or traffic conditions do not allow (Alaska, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Utah, Tennessee); or

Tennessee §55-8-132. …if possible with due regard to safety and traffic conditions…

Oklahoma §47-11-314. 1…if possible and with due regard to the road, weather, and traffic conditions… - a lane change is prohibited by law (Iowa).

Iowa, §321.323A. b. If a lane change under paragraph "a" would be impossible, prohibited by law, or unsafe…

Driver's Responsibility to Slow Down

Move Over laws in select States (i.e., Arkansas, Vermont) do not require drivers to slow down or reduce travel speeds. In States that do, provisions related to a driver's responsibility to reduce speeds often are qualified by the ability to change lanes; if a lane change cannot safely be made, the driver must reduce the speed of the vehicle. Legislation in most States requires motorists to generally slow to a "safe" or "reasonable" speed. Other States include more specific speed provisions. Consider the following examples.

State Move Over laws require:

- a driver to keep the vehicle under control when approaching or passing an emergency scene (South Carolina);

South Carolina §56-5-1538. (F) The driver of a vehicle shall ensure that the vehicle is kept under control when approaching or passing an emergency scene…The exercise of control…is that control possible and necessary by the driver to prevent a collision, to prevent injury to persons or property, and to avoid interference with the performance of emergency duties by emergency personnel. (G) A person…approaching a stationary authorized emergency vehicle…shall proceed with due caution, significantly reduce the speed of the vehicle…

- a "safe" or "reduced" speed but no suggested speed is provided (Alabama, Alaska, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, Wisconsin);

Alaska §28.35.185. (2) …shall slow to a reasonable and prudent speed…(Maine §2054-9.B and Pennsylvania §3327 contain similar language).

Indiana §9-21-8-35. …a person who drives an approaching vehicle shall (2) proceeding with due caution, reduce the speed of the vehicle, maintaining a safe speed for road conditions, if changing lanes would be impossible or unsafe (Illinois §625.5/11-907, Kentucky §189.930(b), Missouri §304.022, and North Dakota §39-10-26.2 contain similar language).

Minnesota §169.14.3. (a) The driver of any vehicle shall…drive at an appropriate reduced speed when approaching or passing an authorized emergency vehicle stopped with emergency lights flashing on any street or highway…(Montana §61-8-346 contains similar language).

Kansas §8-1530(2). …the driver shall proceed with due caution, reduce the speed of the motor vehicle and maintain a safe speed for the road, weather and traffic conditions (Michigan §257.653a, Ohio §4511.21.3, and Oklahoma §47-11-314 contain similar language). - a "safe" or "reduced" speed and a suggested speed is provided (West Virginia);

West Virginia §17C-14-9a. (2) Proceed with due caution, reduce the speed of the vehicle, maintaining a safe speed not to exceed fifteen miles per hour on any non-divided highway or street and twenty-five miles per hour on any divided highway depending on road conditions, if changing lanes would be impossible or unsafe.

- a "safe" or "reduced" speed "under the posted speed limit" but no suggested speed reduction is provided (Georgia, Iowa, Nevada); and

Georgia §40-6-16. (2) If a lane change under paragraph (1) of this subsection would be impossible, prohibited by law, or unsafe, reduce the speed of the motor vehicle to a reasonable and proper speed for the existing road and traffic conditions, which speed shall be less than the posted speed limit, and be prepared to stop (Iowa §321.323A contains similar language).

Nevada §484.364. (a) Decrease the speed of his vehicle to a speed that is: (1) Reasonable and proper, pursuant to the criteria set forth in subsection 1 of NRS 484.361; and (2) Less than the posted speed limit, if a speed limit has been posted. - a "safe" or "reduced" speed "under the posted speed limit" and a suggested speed reduction is provided (Florida, South Dakota, Texas, Wyoming).

Florida §23.316.126. 2. Shall slow to a speed that is 20 miles per hour less than the posted speed limit when the posted speed limit is 25 miles per hour or greater; or travel at 5 miles per hour when the posted speed limit is 20 miles per hour or less, when driving on a two-lane road, except when otherwise directed by a law enforcement officer (South Dakota §32-31-6.1 contains similar language).

Wyoming, §31-5-224. (ii) When driving on a two (2) lane road, shall slow to a speed that is twenty (20) miles per hour less than the posted speed limit, except when otherwise directed by a police officer.

Driver Education

Because the effectiveness of Move Over laws relies heavily upon driver cooperation, the "Move Over America" partnership and AAA initiated national public information campaigns in an effort to raise awareness of driver responsibilities under these laws. Select States, such as Florida, have also included State-mandated driver education initiatives and enforcement directives as part of their legislation.

Florida §316.126. 2 (c) The Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles shall provide an educational awareness campaign informing the motoring public about the Move Over Act. The department shall provide information about the Move Over Act in all newly printed driver's license educational materials after July 1, 2002.

The effects of recently initiated public information campaigns may not yet be realized. Anecdotally, responders in a number of States have expressed concern over the lack of awareness among drivers regarding Move Over laws and the subsequent ability of these laws to enhance responder safety and realize additional associated benefits. This finding suggests that State-mandated driver education initiatives and enforcement directives should be more broadly incorporated into related legislation in an effort to ensure an appropriate level of effectiveness.

Implementation Challenges and Resolutions

Noted implementation challenges or shortcomings when introducing and enacting Move Over laws include the following:

- Move Over law provisions may not include all traffic incident responder types;

- Move Over laws may be difficult to enforce; and

- lane change requirements could pose additional risks.

"Emergency Scene" Definition May Not Include All Responder Types

The definition of an "emergency scene" and/or "authorized emergency vehicles" may not include the presence of transportation, towing/recovery, or service patrol personnel and/or vehicles despite their common exposure to danger. Hence, these laws may offer no potential safety enhancement for these responder types. Concurrent laws related to the definition of an "emergency vehicle" (i.e., red, white, and blue vehicle-mounted flashing lights are typically reserved for law enforcement, fire and rescue, and EMS while amber lights are typically reserved for transportation, towing/recovery, or service patrol vehicles) may challenge the ability to expand the Move Over law to include the broader set of responders.

Response

State Move Over laws that include transportation, towing/recovery, or service patrol personnel and/or vehicles, as well as emergency responders and/or vehicles under the purview of Move Over laws should be considered as "model legislation." These States include Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Tennessee, Utah, and Wisconsin. Responder safety-related statistics can be presented as the basis for introducing inclusive original legislation or expanding current legislation to include transportation, towing/recovery, or service patrol personnel and/or vehicles, as well as emergency responders and/or vehicles. Demonstrated, united support from each agency or industry affected can significantly assist in advancing the legislation.

Move Over Laws May Be Difficult to Enforce

The effectiveness of Move Over laws is challenged by both a lack of motoring public awareness and limited law enforcement activity resulting from logistical and resource constraints. Only a single State was observed to include mandated driver education initiatives as part of its Move Over legislation. None of the Move Over laws observed included requirements for roadside signing to remind drivers of their responsibilities to change lanes and/or reduce speeds. In the event of an incident, on-scene responders are occupied with incident management duties and unable to concurrently consider enforcement of Move Over law violators. The authority to enforce the law is limited to enforcement personnel. For minor incidents, on-scene responders may be limited to transportation, towing/recovery, or service patrol personnel; law enforcement personnel may not be on-scene to provide enforcement capabilities. If the provisions of the law are vaguely defined (i.e., driver shall maintain a "safe" speed or provide as much space as "practical"), the law may be especially difficult to enforce.

Response

State Move Over laws that include explicit yet reasonable provisions for driver action should be considered as "model legislation." The language "yield right-of-way by moving to a lane that is not adjacent to the authorized emergency vehicle" (Alabama, California, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, North Dakota, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia) and "reduce speed to 20 miles per hour under the posted speed limit" (Florida, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming) is sufficient to support enforcement.

Select law enforcement agencies have established additional "sting" operations to properly enforce their Move Over laws. For example, Florida, Georgia, and Missouri routinely assign law enforcement personnel in pairs so that one officer can monitor passing traffic. These targeted enforcement efforts may be combined with other enforcement activities to enhance personnel efficiency. Associated fines and penalties for violating Move Over laws vary significantly. Anecdotally, many law enforcement agencies feel that existing fines and penalties are too low to deter violators effectively. As one exception, motorists failing to change lanes in Missouri may face involuntary manslaughter charges. Steeper fines and penalties, combined with an effective public information campaign, may help to encourage compliance.

Requiring Drivers to Change Lanes Could Pose Additional Risks

Concerns have been expressed in regard to Move Over law provisions that require a driver to change lanes and/or slow down, citing the potential for sudden, and perhaps unsafe, lane changes or a propensity for slowing vehicle to be struck from behind. In an early version of California §21809 (SB 800) first introduced in 2005, the California Highway Patrol expressed concern that the lane change mandate "could create chaotic and dangerous situations at crime and collision scenes on the States freeways." As a result of these concerns, the Governor of California vetoed the bill.

Response

Continuing with the example provided above, California's Move Over law was re-introduced again a year later (SB 1610) with the following qualifying language for changing lanes: "with due regard for safety and traffic conditions, if practicable and not prohibited by law." The revised version of the bill also included a required speed reduction if the driver is prevented from making a lane change. In this instance, CHP noted that the provisions of the bill "will help to deter motorists from reckless driving that endangers the lives of emergency responders." California's Move Over law went into effect on July 1, 2007.

Effective State Move Over laws should include appropriate qualifying language that:

- leaves the decision of whether to change lanes up to the driver based on prevailing traffic and roadway conditions (Alabama, California, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, North Dakota, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia), and

- provides an alternative action of reducing speeds if a lane change maneuver cannot be performed safely (Florida, South Dakota, Texas, Wyoming).

This example also emphasizes the need for demonstrated, united support from affected agencies. Law enforcement agencies ultimately enforce Move Over laws and as such, are important partners in defining, developing, and enacting related legislation. Concerns related to their ability to enforce Move Over laws are often valid. More successful and effective Move Over laws and stronger relations between transportation and law enforcement agencies result when agencies work closely with law enforcement partners to demonstrate the potential benefits related to responder safety and to address their concerns related to enforcement.

December 2008

FHWA-HOP-09-005