INFORMATION SHARING FOR TRAFFIC INCIDENT MANAGEMENT

2.0 INFORMATION EXCHANGE BY PUBLIC AND PRIVATE RESPONDERS

Generally defined, a highway incident is a period of impact due to a vehicle crash, breakdown, or special traffic event in which normally flowing traffic is interrupted. The incident can vary in severity from a breakdown on the shoulder, to roadway blockage from a multi-vehicle crash, to a regional evacuation from a natural or man-made disaster. The scale of the incident influences the scope of the response in terms of agencies involved and resources needed to manage the incident.

This non-recurring congestion results in a reduction in roadway capacity or an abnormal increase in traffic demand. Normal operations of the transportation system are disrupted. Incidents are a major source of roadway congestion, contributing to millions of hours of delay and productive hours wasted as well as causing a direct negative effect on roadway safety and operations.

Incidents are classified in the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices 2 based upon duration, each with unique traffic control characteristics and needs:

- Major - typically traffic incidents involving hazardous materials, fatal traffic crashes involving numerous vehicles, and other natural or man-made disasters. These traffic incidents typically involve closing all or part of a roadway facility for a period exceeding 2 hours. Traffic control is implemented.

- Intermediate - typically affect travel lanes for a time period of 30 minutes to 2 hours, and usually require traffic control on the scene to divert road users past the blockage. Full roadway closures might be needed for short periods during traffic incident clearance to allow traffic incident responders to accomplish their tasks. Traffic control is implemented.

- Minor -disabled vehicles and minor crashes that result in lane closures of less than 30 minutes. On-scene responders are typically law enforcement and towing companies, and occasionally highway agency service patrol vehicles. Diversion of traffic into other lanes is often not needed or is needed only briefly. It is not generally possible or practical to set up a lane closure with traffic control devices for a minor traffic incident.

Incident response activities are interdependent, and responders must, therefore, effectively exchange information in order to have the most effective, rapid, and appropriate response to a highway incident. Responders must agree to basic task definitions, lines of authority, organizational issues, and assignments of responsibility. Information must be shared across a variety of boundaries, including technological, organizational, and institutional. While technology can overcome various interoperability issues, successful information sharing begins first with stakeholders' commitment to cooperative partnerships to address organizational and institutional barriers. Overcoming these barriers permits coordinated and integrated response to incidents, and those agencies that work together effectively have found ways to address the challenges presented by these barriers. The primary reference for this section is the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Report 520, Sharing Information between Public Safety and Transportation Agencies for Traffic Incident Management (2004). 3 This report identifies four broad categories for information exchange:

- Face-to-face

- Remote voice

- Electronic text

- Other media and advanced systems

This section will first introduce some traffic incident management concepts with respect to coordination and communications between response agencies. This will be followed by brief descriptions of the four areas of information sharing practices relative to the three categories of this document's target audience. Successful programs typically use several practices within an environment that support and encourage information exchange.

Traffic Incident Management Concepts

Traffic incident management is the planned, coordinated effort between multiple agencies to deal with incidents and restore normal traffic flow as safely and quickly as possible. This effort makes use of technology, processes, and procedures to reduce incident duration and impact to:

- Reduce incident detection, verification, response, and clearance times to quickly re-establish normal capacity and conditions

- Enhance safety for motorists and field/safety personnel

- Reduce the number of secondary crashes that occur as a result of the primary incident

- Reduce motorist costs, vehicle emissions, and business costs

- Allow resources to resume non-incident activities

The Incident Command System and Unified Command

Incident Command System

Incident responders, particularly law enforcement and fire-rescue personnel, use the federally adopted Incident Command System (ICS), for all types of incident management. ICS was originally developed in the 1970s as an approach for managing responses to rapidly moving wildfires. In the 1980s, federal officials transitioned ICS into the National Incident Management System (NIMS), the basis of response for highway and other incidents. ICS is a standardized, on scene traffic incident management concept that allows responders to adopt an integrated organizational structure without being hindered by jurisdictional boundaries.

ICS includes five major functional areas shown in Figure 1: command, operations, planning, logistics, and finance and administration. These major areas are further broken down into specialized subunits. The area of Intelligence may be included if required.

Command – overall authority associated with the incident, responsible for determining size and magnitude of response and involved personnel

Operations – activities necessary to provide safety, incident stability, property conservation, and restoration of normal highway operations

Planning – activities associated with maintaining resource/situation status, development of incident action plans, and providing technical expertise/support to field personnel.

Logistics – services and support for incident response effort in the form of personnel, facilities, and materials.

Financial and Administration – tracking of incident costs/accounts for reimbursement.

Intelligence – analysis and sharing of information and intelligence during the incident.

Figure 1. Incident Command Functional Areas 4

ICS outlines roles and responsibilities for incident responders. Rather than defining who is in charge, ICS provides the management structure for who is in charge of what. ICS allows agencies to work together using common terminologies and operating procedures, leaving command personnel with a better understanding of other agencies’ priorities.

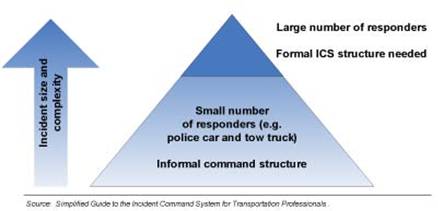

ICS is scalable to the level appropriate for the incident and surrounding conditions. Responses can be transitioned from small, single agency to large, multi-agency and vice-versa with minimal adjustments for the agencies involved as shown in Figure 2. ICS provides the structure to allow flexible, agile responses that adapt to real-time field conditions.

Figure 2. Incident Command Structure Needs 5

Unified Command

Unified command (UC) defines the application of ICS when there is more than one agency with incident jurisdiction or when an incident crosses multiple jurisdictions. UC provides a management structure that allows agencies with incident responsibilities to jointly work within an established set of common objectives and strategies that include:

- Agency assignments

- Incident priorities

- Assignment of agency objectives

- Communications protocols

- Knowledge of duties within agency responsibilities

- Acquisition and allocation of materials and resources

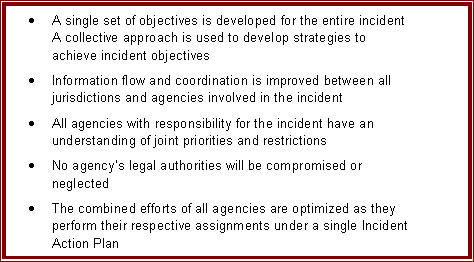

When applied effectively, UC facilitates interagency communications and cooperation, leading to efficiencies in response. UC allowsall agencies with jurisdictional authority to provide managerial direction at an incident scene while maintaining a common set of objectives and strategies. Command staff report directly to the Incident Commander. The identity of the Incident Commander is dependent on the priority mission at the time. Until the injured are treated and moved, fire-rescue or emergency medical services (EMS) will probably be in charge. When the priorities shift to investigation, law enforcement will take over. As the incident moves into clean-up/recovery, command can shift to the transportation agency or towing contractor. Personnel participate actively until they no longer have a role at the incident. During this process, other agencies have the opportunity to participate in decision making and provide direction to their own personnel; however, overall charge resides in the Incident Commander. A key component of success is the ability to communicate between the varied entities with roles to play in the response effort. Another key factor is the strength of interpersonal relationships, often built in other settings, that allows responders to communicate clearly and effectively with each other during the management of an incident. Some key advantages of UC, as listed in the United States (U.S.) Department of Homeland Security’s National Incident Management System Manual,4 are:

Figure 3. Advantages of Using Unified Command 4

Information Sharing Practices 3,6,7

Face-to-Face

Face-to-face communications between incident responders are the most common form of information exchange. Personal exchanges are most effective when responders are able to communicate openly and directly share information and coordinate responses. These exchanges occur both at an incident scene and within shared facilities; and they include both communications during an incident and various planning or debriefing teams that meet outside the course of an incident.

On Scene

Law enforcement and fire-rescue incident responders are familiar with, and frequently use, the ICS. Responders from transportation agencies are beginning to incorporate ICS applications in their actions both on scene and at traffic management centers.

Most highway incidents involve law enforcement, transportation personnel, and a private tow truck and, therefore, usually do not require formal implementation of ICS. However, when a large-scale, complex incident requires a multiple-agency response, these personnel must understand how ICS defines;

- Operational task responsibilities,

- Chains of command, and

- Scene management practices

Incident responders located on scene work within the operations functional area of ICS. One person directs all incident-related operational activities and reports back to the Incident Commander. Depending on the complexity of the incident, subunits within this structure establish tactical objectives for each phase of response. Resources refer to the personnel and equipment needed to manage the response. The major organizational elements for the operations area are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Organizational Elements 4

More incident responders are beginning to be trained in ICS and UC in which multiple agencies respond to a single incident. As stated in the Traffic Incident Management Handbook, 1 UC facilitates cooperation and participation between multiple agencies/jurisdictions through the following functions:

- Provide overall response direction

- Coordinate effective communication

- Coordinate resource allocation

- Establish incident priorities

- Develop incident objectives

- Develop strategies to achieve objectives

- Assign objectives within the response structure

- Review and approve incident action plans

- Insure the integration of response organizations into the UC structure

- Establish protocols

Following UC principles permits agencies to more cooperatively work together to achieve common objectives. The required teamwork and communications helps to avoid duplication of tasks and activities.

For example, the first responder on scene is responsible to assess the incident, secure the scene, provide emergency care, and call for additional response resources. As response activities occur, incident command shifts as the priority mission changes:

- Emergency response to treat and transport victims and establish scene safety

- Investigate incident

- Clean up/restore/repair incident scene

Effective communications between agencies is critical for successful management of the incident and resumption of normal traffic flow.

Shared Facilities

Shared facilities encompass a variety of locations in which multiple agencies operate jointly, both during the course of an incident and in settings that include debriefing and planning sessions. Traffic operations/management centers (TOC/TMC) can house transportation, public safety, and other personnel who are able to share both communications and information systems, allowing the facility to become a focal point for sharing incident status information in the region. Examples of other shared facilities include 911/dispatch centers and mobile command posts. Co-location of personnel, often initiated through an inter-agency Memoranda of Understanding/Agreement (MOU/MOA), allows partners to work side-by-side within the facility, strengthening relationships between responders as a result of the interpersonal contact. Such facilities evolve to become the focal point of information sharing in a region, beginning with information exchange through face-to-face communications and shared system access.

Planning/Debriefing Sessions

Another important means of information exchange is via incident-related, non-emergency meetings between responders. Such meetings are often held by multi-disciplinary traffic incident management (TIM) teams and task forces that debrief major incidents in order to find ways to improve TIM response. Recommendations from TIM teams range from immediate response improvements to longer term strategic suggestions that may require time, resources, and other commitments for implementation. Regular TIM team meetings provide a neutral environment to effectively discuss lessons learned as well as resolve issues that may have arisen during the management of an incident. Debriefing steps should include:

- Incident re-creation

- Agency input for aspects that worked well and those that did not

- Discussion of potential improvements

- Development of consensus for future events

- Documentation of findings and update of response plans, if appropriate

Remote Voice

The most common ways incident responders share information between the incident scene, operations centers, and public safety facilities using voice communications are:

- Land line telephones

- Wireless telephones

- Land mobile radios

These remote voice tools are often used in combination by all of those involved in the incident and response:

- A disabled or passing motorist dials 911 or a non-emergency assistance number via cellular telephone to notify public safety personnel about an incident

- First responders relay information about the incident via their land mobile radio network

- Response agencies speak to each other via the wired telephone network to coordinate their responses

With voice communications to transmit information to and from the incident scene, responders can quickly adjust to changing conditions. Responders must use clear-text transmissions, mandated by NIMS-ICS guidelines 4 , to prevent misunderstandings of their transmissions. Remote voice information exchange also facilitates the adjustment of response resources and provides an easily used pipeline of information to information dissemination services for the motoring public.

Land-line Telephones

Wired telephones are sometimes the only means available to share information between separately housed response entities. Wired telephones include voice and facsimile transmissions. They are critical for public safety communications, including 911 calls, and some portions of the cellular network make use of the land-line telephone network.

Wireless Telephones

Cellular phones, and less commonly used satellite telephones, are used between on scene and in-facility incident responders. Motorists, both those involved in an incident as well as passers-by, use cellular phones to call for assistance; however, there can be accuracy issues as unfamiliar motorists incorrectly identify incident locations. Cameras in cellular telephones have become common place and can be used to wirelessly transmit visual information; however, image transmission via wireless telephone is usually not a first action by incident responders. Cellular capabilities are improving as the network matures—both in terms of use of the network and cellular phone features (push-to-talk networks that sometimes replaces land mobile radios, text messaging, internet access, and still/video camera phones).

Land Mobile Radios

Radios can be used by incident responders to communicate directly with each other. While they are typically used within a single agency because of interoperability issues, sharing the radio frequency with other incident responders can facilitate response. For example, service patrol personnel may operate on a law enforcement radio network to communicate directly with law enforcement, both at the incident scene as well as with a dispatch center, with the result that response times may be reduced. Safeguards, including specialized training and procedures, must be put into place to overcome security concerns about sensitive information for shared communications with law enforcement agencies. One alternative is to allow civilian personnel to listen, but not talk, over the radio. Another benefit of sharing radio communications is that transportation personnel can handle minor incident response issues and communications, freeing public safety responders to handle emergency issues.

Electronic Text

Electronic text messaging is an automated way to share incident-related information quickly with large numbers of agencies and people with minimal resources. While not the primary method for inter-agency communications, electronic text messaging can be used to share information broadly and quickly. Categories of electronic text systems are:

- Alphanumeric pagers

- Traffic incident-related systems, including computer aided dispatch (CAD)

Pagers can be used to transmit abbreviated messages to incident responders; email text can be more detailed. Both are quick means to broadcast information to predefined response groups. Additionally, pages and email blasts can be sent to the public as a subscription service, sometimes in conjunction with 511 traveler information services, so motorists can be advised of traffic conditions. If necessary, they can avoid becoming part of the incident queue through route diversions and adjustments, reducing the overall incident’s impact and duration.

CAD sharing by law enforcement is becoming more common. Because the information entered into CAD is sensitive, non-law enforcement personnel must undergo certain precautions (background checks, training, etc.) to satisfy security requirements. Read-only, sometimes filtered, access allows other responders to call for and adjust response resources more effectively. For example, transportation personnel can monitor CAD systems to track incident progress and adjust their own response efforts. CAD systems also become a valuable record keeping tool when debriefing or analyzing an incident’s response for areas of improvement. Interoperability issues can impact information exchange using CAD, since many CAD systems are proprietary and, therefore, pose technological challenges to sharing information. Integration can occur; however, institutional and technological barriers must be overcome to do so effectively.

Other Media and Advanced Systems

Other integrated technologies can be used to share incident-related information between transportation and public safety agencies. Advanced traffic management systems (ATMS) normally include surveillance and communications technologies. They also address the needs of two different audiences: response personnel from the public and private sectors, and the motoring public trying to navigate around an incident.

Intelligent transportation systems (ITS) field devices for incident detection and verification include in-ground and mounted sensors and closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras. Visual verification allows increased accuracy of response because agencies can see what resources are needed for incident response and repair and, therefore, dispatch them more quickly and accurately. Images and detection data can be readily shared with co-located agencies or remotely if integration needs have been addressed. Visual imagery allows response agencies to adjust their response, manage traffic, and disseminate information.

Information dissemination occurs through the use of electronic message signs (both portable and fixed), highway advisory radios, and telephone- and web-based 511 traveler information services. Information shared in this manner can be received by motorists, who can then evaluate roadway conditions, and decide if and how to adjust their travels during the course of an incident. This same information is useful to response agencies that need to travel on the roadway network quickly and efficiently, helping them reduce their own response times. Real-time information regarding roadway conditions, congestion, and scene details helps responders arrive, respond, and leave an incident scene more quickly.

ITS media allow more accurate, timely, and reliable information sharing through an important technological set of tools that can be used by multiple responders to support traffic incident management response efforts. However, because ITS applications can have greater communications bandwidth requirements than remote voice or electronic text methods, especially when video is involved, the quality of the information shared may be impacted. For example, video may need to be reconfigured to snapshot or streamed images over the internet. Dynamic map displays, part of a traveler information system, may not provide the level of detail desired for the roadway network because of the time needed to load and refresh the information. These issues must be addressed during the developmental stage so that the varying audiences can obtain the correct information and appropriate level of detail for effective actions and decision making.

Information Sharing Case Studies

Examples of successful information sharing between incident responders are numerous; some key examples are highlighted below.

NCHRP Report 520 Case Studies

NCHRP Report 520, Sharing Information between Public Safety and Transportation Agencies for Traffic Incident Management (2004)3 reviews the effectiveness of information sharing for the following nine locations with active traffic incident management programs that involve public safety, transportation, and other public and private sector entities. Key stakeholders are transportation departments and local/state law enforcement agencies. Whether or not these agencies are physically co-located at the common facility, the sites provide varying examples and levels of success with the information sharing practices previously described in this section for the purposes of incident detection and notification, response, and site management.

- Albany – close working relationships between two transportation agencies (New York Department of Transportation (DOT) and New York State Thruway Authority) two law enforcement divisions (New York State Police and Albany Police Department); regional coordination and various information-sharing applications in place for a long time period.

- Austin – Texas DOT, Austin Police Department, Austin Fire Department, and Travis County EMS are co-located in a TMC facility that serves as a focal point for information exchange through cooperatively developed technologies. The agencies have shared radio and video systems, and they have also integrated the CAD and traffic management systems.

- Cincinnati – Ohio and Kentucky transportation agencies have joined to regularly and routinely share traffic information through the Advanced Regional Traffic Interactive Management Information System (ARTIMIS). Strong regional TIM teams convene at the center to handle major incidents with involvement by relevant public safety and transportation partners in the region. This mature interagency operation includes a partnership with CVS Pharmacies to provide roadway service patrols.

- Minneapolis – Minnesota DOT and Minnesota State Police operate in a co-located TMC facility with a shared radio communications system (800 MHz) that includes workstations for media, and transportation and law enforcement. Additional joint communications centers throughout the state are also in place.

- Phoenix – Arizona DOT, Maricopa County DOT, and Phoenix Fire Department share radio systems, phone lines, traveler information workstations, facsimile and pagers, and CCTV images in their efforts to overcome institutional barriers to information sharing.

- Salt Lake City – strong inter-agency relationships between Utah DOT and Utah Highway Patrol leveraged upgrades resulting from the 2000 Winter Olympics to enhance information sharing both in the operations facility and on scene. Technical challenges were overcome by incorporating the same radio communications and CAD systems. Agencies share video images as well.

- San Antonio – strong institutional framework and joint activities of key transportation and public safety agencies have led to highly integrated communications and information sharing. Representatives include Metropolitan Transit Authority, San Antonio Public Works Department, Alamo Dome, San Antonio Police Department, Bexar County Sheriff Department, EMS, county health departments, and private sector towing and recovery providers. Texas DOT (TxDOT) and the San Antonio Police Department work together in the TransGuide Operations Center, a central point for incident and emergency response.

- San Diego – CalTrans and the California Highway Patrol have undertaken a CAD interface project to bridge communications between transportation and public safety agencies; while the project itself was only partially successful, the technical and institutional barriers identified have laid the foundation for a similar future project that will build upon the agencies’ commitment to share information.

- Seattle – Washington DOT (WSDOT), Washington State Police (WSP), and the Washington State Legislature share a common focus that has led to coordinated traffic incident management and strong information sharing practices in the Seattle region. Together WSDOT and WSP have developed and implemented advanced technologies for inter-jurisdictional and inter-disciplinary communications.

NCHRP Report 520 results for the categories of information sharing described in this section are presented in Table 1, taken directly from the report. Further detailed research can be found in the report.

Table 1. Methods of Sharing TIM Between Transportation and Public Safety Agencies at Survey Locations.3

| Geographical Region |

Face-to-Face |

Remote Voice |

Electronic Text |

Other Media and Advanced Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Albany, NY |

State Police co-located with State DOT at one center; State Police co-located with Thruway Authority at another center. |

State DOT Service Patrols share public safety radios; State Police and Thruway share a radio system and dispatchers; Senior staff use commercial wireless service “talk groups.” |

Joint CAD system shared at Thruway center. |

ATMS data, images, and video shared remotely through experimental wireless broadband service. |

Austin, TX |

State DOT, city fire and police depts., and county EMS will be co-located at center. |

Service Patrols equipped with local police radios. |

Capability under development to share traffic incident data from public safety CAD data remotely. |

Control of transportation CCTVs shared with local police. |

Cincinnati, OH |

Transportation center hosts regional Incident Management Team operations. |

ARTIMIS shares public safety radios; multiple agencies use commercial wireless service “talk groups.” |

Capability under development to share CAD data with ARTIMIS. |

Transportation CCTV images available on traveler information website. |

Minneapolis, MN |

State Patrol and State DOT staff co-located at a regional center. State Patrol and service patrol staff co-located at another location. |

State Patrol and State DOT share the 800 MHz radio system. Senior staff use of commercial wireless service “talk groups.” |

Service Patrols have read-only terminals from State Patrol CAD. State DOT can access State Patrol CAD. |

State DOT CCTV and other traffic management systems are shared with State Patrol. |

Phoenix, AZ |

— |

Service Patrols equipped with State Patrol and State DOT radios. |

State DOT highway condition workstations provided to local fire dept. and emergency services div. County DOT incident response teams use alphanumeric pagers. |

State DOT CCTV shared with local fire dept. |

Salt Lake City, UT |

Highway Patrol and State DOT staff co-located at the regional center, but separated by elevated soundproof glass partition. |

All Highway Patrol and State DOT field units use the same radio system and dispatchers. Service Patrols are fully integrated into law enforcement radio system. |

State Patrol CAD shared with State DOT |

State DOT CCTV and other traffic management systems are shared with Highway Patrol. |

San Antonio, TX |

Local Police and State DOT co-located at the regional center. |

Service Patrols equipped with local police radios. New radio system will provide common channels for State DOT and local police and fire. |

Incident data from local police CAD shared with State DOT traveler information system. |

State DOT CCTV images are shared with local government and news agencies. |

San Diego, CA |

State Patrol and State DOT co-located at the regional center. |

Service Patrols equipped with local police radios. |

State DOT has read-only access to Highway Patrol CAD. |

Incident information from Highway Patrol CAD is provided to State DOT traveler information website. |

Seattle, WA |

— |

Service Patrols equipped with State Patrol radios. Intercom system (with handsets) is used between State DOT center and State Patrol 9-1-1 call center. |

State DOT partially shares State Patrol CAD system. State DOT has CAD terminal for entering traffic incident information. |

State DOT CCTV shared with State Patrol (includes control of cameras). |

All locations use standard telephones and facsimile machines for information sharing.

ARTIMIS = Advanced Regional Traffic Interactive Management Information System.

ATMS = advanced traffic management system.

CAD = computer-aided dispatching.

CCTV = closed-circuit television.

DOT = department of transportation.

EMS = emergency medical services.

Additional Case Studies

Kentucky’s Intelligence Fusion Center 8

Kentucky’s Intelligence Fusion Center, a unified hub that uses a remotely accessed data sharing and analysis system, coordinates and connects all levels of law enforcement and public safety agencies as well as the private sector. The center’s goal is to improve intelligence sharing between responders. The public is also encouraged to report suspicious activities through a telephone hotline. While this exchange of information is done primarily in the context of enhancing domestic security and reducing criminal activity, improvements to information sharing also enhance traffic incident management activities as some of the same organizations involved in the center deal with traffic incident management. Agencies involved in the Kentucky Intelligence Fusion Center include:

- Kentucky Office of Homeland Security

- Kentucky State Police

- Kentucky Transportation Cabinet

- Kentucky Department of Corrections

- Kentucky Department of Military Affairs

- Kentucky Vehicle Enforcement

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives

- United States Department of Homeland Security

- Lexington Division of Police

A fusion center is a unified information hub linking all types of information collected by law enforcement and public safety agencies that is necessary to combat criminal activity and domestic and international terrorism; the ultimate result of this linkage is to bring together agencies with common purpose. These same agencies are also charged with the responsibility of being the first responders for emergency and incident management. It is a natural extension of this mechanism to also serve as the basis of the necessary communication, coordination, and cooperation among these agencies charged with first response to traffic incidents. To this end, the capabilities of the Kentucky Intelligence Fusion Center, relative to information sharing for incident response, include:

- Shared database to assist federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies with information requests, reporting requirements, and /or performance measures

- Receipt of law enforcement field reports from in-car mobile data computers

- Radio communications dispatching for state police

- AMBER Alert notification

- Connection to multiple intelligence and information sharing networks

- Traffic and TIM center monitoring of highway construction, maintenance, weather, and other events

- Monitoring and updating of the Kentucky 511 traveler information system

- Monitoring of regional traffic center Web sites in Louisville, Lexington, and the Northern Kentucky-Cincinnati area

FDOT District Five and Florida Highway Patrol 9

FDOT’s District Five Road Ranger Service Patrol is currently operating on the State Law Enforcement Radio System (SLERS). This pilot project is in the Orlando metropolitan area where the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) TMC is co-located with the Florida Highway Patrol (FHP) Communications Center. The radio system allows Road Rangers to communicate directly with FHP Troopers at incident scenes and also with FHP dispatchers. Response times have been reduced as incidents are identified more quickly by multiple responding entities, either by having a Road Ranger come upon a disabled vehicle and making the first call into the dispatch center, or by having a Road Ranger hear the dispatch call over the radio.

These varied locations have demonstrated that no single approach to information sharing is best. Local factors and organizational issues must be identified and addressed to achieve effective interagency communications practices that are influenced by interoperability issues and interpersonal relationships.

SAFECOM 10, 11

The lack of interoperability between emergency responders—the ability for agencies to exchange voice or data with one another via radio communication systems—has been a long-standing, complex, and costly problem that has affected their responses to incidents and emergencies. In addition to incompatible communications equipment, responders also have to deal with funding issues, insufficient planning and coordination, a limited radio spectrum, and limited equipment standards. Wireless devices can provide some relief, but the cellular network is quickly overwhelmed during an incident or emergency and then becomes unreliable and unavailable. This issue was highlighted during the tragic events of September 11, 2001. As a result, the SAFECOM program was established as a communications program within the Department of Homeland Security’s Office for Interoperability and Compatibility. SAFECOM “provides research, development, testing and evaluation, guidance, tools, and templates on communications-related issues to local, tribal, state, and Federal emergency response agencies working to improve emergency response through more effective and efficient interoperable wireless communications.”10

SAFECOM is a practitioner-driver program; i.e., local and state emergency responder input and guidance are heavily relied-upon in the pursuit of solutions to interoperability issues. Based upon the results of a pilot initiative in ten urban areas completed in 2004, five factors critical to the success of interoperability were identified in an “Interoperability Continuum” or guiding principles as follows and shown in Figure 5:

- Governance

- Standard operating procedures

- Technology

- Training and exercises

- Usage

Figure 5. SAFECOM Interoperability Continuum 12

Public safety communications requirements for voice and data interoperability were first released in 2004. These requirements serve as a first step for establishing base-level communications and interoperability standards for emergency response agencies, a process that is expected to take up to 20 years to achieve. In the interim, SAFECOM has11:

- Created the Federal Interagency Coordination Council (FICC) to coordinate funding, technical assistance, standards development, and regulations affecting communications and interoperability across the federal government;

- Published a Statement of Requirements which, for the first time, defines what it will take to achieve full interoperability and provides industry requirements against which to map their product capabilities;

- Issued a request for proposals for the development of a national interoperability baseline;

- Initiated an effort to accelerate the development of critical standards for interoperability;

- Created a Grant Guidance document that has been used by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Community Oriented Policing Services, and Office of Domestic Preparedness state block grant program to promote interoperability improvement efforts.

- Established a task force with the Federal Communications Commission to consider spectrum and regulatory issues that can strengthen emergency response interoperability;

- Created a model methodology for developing statewide communications plans;

- Released a Request for Information to industry that netted more than 150 responses; and

- Worked with the emergency response community (local, tribal, state, and federal) to develop a governance document that defines both how SAFECOM will operate and how participating agencies will work within that framework.