Chapter 4. Full-Function Service Patrol Concept

4.1 Background, Objectives, and Scope of an FFSP

Section 2.1 provided the background on existing service patrols while

Section 3.1 discussed justification for changes to an FFSP. FHWA is

anticipating that this Handbook for an FFSP will provide a model for uniform

service across the U.S. and provide additional benefits in reducing congestion.

Section 2.1 provided the background on existing service patrols while

Section 3.1 discussed justification for changes to an FFSP. FHWA is

anticipating that this Handbook for an FFSP will provide a model for uniform

service across the U.S. and provide additional benefits in reducing congestion.

An FFSP program is an essential component of a regional TIM program and

serves to reduce congestion and enhance highway safety. FFSP services should

aim to reduce the impact of traffic incidents by minimizing the duration of

incidents, restoring highways to their full capacity, and applying proper

emergency TTC to enhance safety of other TIM responders and motorists involved

in incidents. An FFSP supports traffic incident response and provides motorist

assistance free of charge. Essential FFSP objectives are defined in priority

order:

- Traffic incident clearance

- Traffic control and scene management

- Incident detection and verification

- Motorist assistance and debris removal

- Traveler information.

A trained FFSP operator uses fully equipped vehicles capable of clearing an

automobile or light truck to a safe location without having to wait for a

wrecker. When vehicle crashes or stalls occur because of a weather event, the

clearance functionality is especially beneficial because private towing company

and automobile club response times can take several hours. The cleared vehicle

presents a significantly reduced hazard at the safe location, allowing a towing

wrecker to pick up the vehicle without further incident. By quickly removing

the hazard from the highway, the FFSP minimizes potential disruptions to other

motorists and reduces the risk of secondary incidents.

The FFSP operator is also sufficiently trained to provide emergency TTC at

incident scenes. This function enhances the safety of responders at the

incident scene and protects motorists passing through the scene. The traffic

control function can also include setting up, maintaining, and removing

emergency detour or alternate routes.

By patrolling the service area, the FFSP can help detect and verify traffic

incidents quickly and initiate a clearance response to motorists requiring

assistance.

The FFSP assists disabled motorists by providing gas or water, changing

tires, performing minor vehicle repairs, or by towing and/or pushing vehicles

off the roadway. The FFSP also assists motorists by providing directions,

tagging abandoned vehicles, removing debris from the roadway, providing rides

to individuals stranded on the highway, and assisting in spill clean-up.

With direct two-way communications, FFSP operators can provide updates on

traffic and roadway conditions to TMC operators as input into traveler

information systems such as 511 and/or DMS.

4.2 Operational Policies and Constraints

Funding and other political, administrative, and institutional constraints

are issues that agencies must overcome and address before implementing an FFSP

program. Specific examples include:

- Program

administration

- The

role and legal limits that an agency, such as a department of transportation,

has in responding to freeway incidents

- Various

roles and responsibilities of stakeholder agencies

- Opposition

from stakeholder agencies

- Commercial

concerns from private enterprise (towing companies, mobile tire repair centers)

- Performance

objectives and policies

- Quick

incident clearance policies

- Open

roads policies

- Operational

policies and associated program costs

- Size

of the program

- Hours

of operation

- Service

area/number of miles covered

- Number

of trucks and operators needed

- Fuel

costs

- Types

of trucks and equipment

- Types

of communications equipment

- Operator

qualifications, training, and certifications

- Dispatcher

qualifications, training, and certifications

- Political

concerns

- Legislative

approval

- Union

concerns

- An

agency’s traditional road-building needs versus operational performance.

4.2.1 Funding

Officials at existing programs routinely acknowledge identifying funding

sources as the biggest challenge in implementing an FFSP. On freeways and other

non-toll highways, service patrol programs typically have been funded through a

State’s transportation funding, from the general fund of tax- and

transportation-related fee revenue (e.g., fuel tax, vehicle registration fees),

and, when applicable, with some Federal funding split. On tollways and

turnpikes, funds for service patrols are generated from the tolls collected on

the facility it serves. In most cases, funding and spending for service patrol

programs competes with other transportation spending within the agency

sponsoring the service patrol. Typical transportation budgets may include major

capital improvements, rehabilitations, operations, maintenance, transit, and

other initiatives. When tax or toll revenues stagnate or decline, agencies are

forced to reduce spending and cut programs. As a result, service patrol programs

are constrained not only by Federal and State budgets but also by tax and toll

revenue collections. Traditional funding mechanisms for an FFSP can include:

- State

legislative appropriations

- State

operations and maintenance funds

- State

traffic and safety funds

- State

general revenue funds

- State

highway trust funds

- Public

safety funds

- Toll

revenues

- MPO

funds

- Federal

surface transportation funds

- CMAQ

funds

- National

Highway System (NHS) funds.

4.2.2 Public Private Partnership

As public agency dollars are stretched and budgets are cut, PPPs can provide

an alternative to funding mutually beneficial programs. Because FFSP programs

are free of charge to motorists and they do not compete with established towing

businesses, it is not feasible to establish a fee-based system for services

FFSP provides. Rather, private companies that benefit from exposure to

motorists, fewer crashes, and open highways will benefit from sponsoring an

FFSP. Private sponsorship of a program can expand service hours, frequency of

coverage, coverage area, and/or services provided. An example of this benefit

is State Farm Insurance Company’s 2-year sponsorship of the Road Ranger program

on the Florida Turnpike. This PPP promotes highway safety through State Farm

Insurance Company and provides free 24 hour roadside assistance along Florida’s

Turnpike. In 2004 State Farm

pledged $850,000 to the Road Rangers program to support motorist assistance. Other private funding source examples

include pharmacies, motor clubs, and wireless telephone carriers. An agency

should check State and local rules and laws to determine whether private

advertising or PPP programs are allowed to partially or fully fund an FFSP and

if not, explore options to allow such assistance.

An agency developing major transportation-based PPP programs such as high

occupancy toll (HOT) lanes or new tollway facilities often develop specific

contract terms for the financing, management, operations, level-of-service, and

maintenance of the facility for a period of time. Contract terms within these

major PPP programs should also include requirements for the developer or

concessionaire to provide an FFSP program on the facility. The result is that

the FFSP cost is enveloped in the overall program financing. This method will

benefit the public by providing the service and benefit the private company by

keeping facility traffic moving, potentially increasing toll collection

revenues from motorists using the facility because of reliable trip times.

4.2.3 Educating Decision-Makers and Stakeholders

Benefit and cost evaluations of service patrols have consistently shown

positive returns on the investment. However, some decision-makers often view

these programs as a value-added service to the basic mission of a transportation

or public works agency. As a result, funding for FFSPs can be constrained by

the support of decision-makers within the agency and by the operational mission

of the agency. Agencies attempting to implement an FFSP program should be

prepared to explain to decision-makers the benefits of quick clearance and how

FFSP programs can reduce congestion and improve safety.

4.2.4 Institutional Coordination

An important aspect in the success of an FFSP program is the involvement of

and the relationship between the TIM and traffic operations stakeholders.

Agencies should develop a multi-agency coalition and institutional framework to

support, protect, and fund the program. The coalition should include

stakeholders such as:

- State

and local law enforcement

- Fire

services

- EMS

personnel

- Departments

of Transportation

- MPO

or Association of Governments

- Local

highway/maintenance departments

- TMCs

- Media

personnel

- Towing

and recovery companies.

Because FFSP programs can provide positive impacts beyond their

jurisdictional boundaries, stakeholder agencies outside the service area or

operational responsibility should also be included. For example, safety and efficiency

improvements from an FFSP on a freeway can positively impact an arterial

network. Establishing the coalition and identifying the stakeholders should

begin in the early stages of planning an FFSP program so that each of the

stakeholder’s unique needs can be addressed. The performance of the FFSP and

partnership of the stakeholder agencies can bolster decision-making support for

the program and in turn influence decision-makers and protect program funding.

In many cases, these agencies can formalize their coalition by creating an MOU,

interagency agreements, endorsement letters, partnering agreements, or joint

operations policy statements.

Multi-agency partnerships can also provide an opportunity for agencies to

pool funding across jurisdictions to provide an FFSP. While one agency may not

be able to afford a stand-alone unit, cost sharing and oversight responsibilities

may provide enough resources for an FFSP across the jurisdictions.

4.2.5 Operational Policies and Program Cost

The operational policies of a TIM program or an FFSP program can affect the

overall budget. In basic terms, an overall program performance goal for traffic

incident clearance can drive the frequency of coverage desired, the number of

hours covered, the total service area, and the extent of the services provided.

These factors affect the overall cost of the program and needed funding.

The following constraints and operational policies affect FFSP programs:

4.2.6 Program Administration and Operational Roles

FFSP programs can be agency operated or privately contracted. When an agency

operates the program, the agency employs the service patrol operations, and the

vehicle and equipment is either leased or procured. Some advantages of an

agency-operated FFSP include:

- Having

direct control of operations and staff performance to support policies such as

open roads and quick clearance

- Changing

operational policies to be executed without contract modifications

- Developing

and maintaining staff skills within agency (whereas in a contracted service, a

change in contractor may cause the program to lose experience and training

developed over time)

- Providing

a mechanism to promote department of transportation customer service

- Avoiding

a contract review and approval process through multiple departments and

divisions of an agency.

A second alternative for implementing an FFSP is for an agency to hire a

contractor to provide patrol services. Agencies typically use their established

bidding or request for proposal (RFP) process to select a private contractor or

towing company to provide the patrol vehicles, equipment, drivers, and service.

The contract must clearly define the operational characteristics of the

program. Typically, the contract is written for bid by vehicle/service hour.

Some advantages of a contracted FFSP include:

- An

agency is not required to procure vehicles, hire personnel, procure special

insurance, or have any special resources to operate the service

- The

contractor handles the vehicle fleet and equipment maintenance

- Potential

cost savings for training can be realized if the contractor has previous

service patrol related experience.

Contracts for FFSPs should include fuel cost clauses to protect both the

vendor and agency from rising fuel costs.

4.2.7 Towing Company Constraints

An agency’s operational policy for an FFSP, whether provided in-house or by

private contractor, needs to prevent conflict with established private towing

industry businesses. Operational policies need to emphasis that the objective

of the FFSP is to clear vehicles from the highway to a safe location and not to

a service station. Furthermore, FFSP programs strictly prohibit operators from

recommending a secondary tow provider. The motorist should choose an operator

or decide from an enforcement agency’s established rotating lists. This

approach will prevent potential civil lawsuits and liability issues. An agency

can prevent misconceptions of the FFSP program by working to establish a

relationship with the local towing industry.

4.3 Description of Full-Function Service Patrols

The following subsections describe the major elements, services, and

capabilities of an FFSP.

4.3.1 Hours of Operation

Consistent with the National Unified Goal (NUG) for TIM, developed through

the National Traffic Incident Management Coalition (NTIMC), the FFSP should be

operated 24 hours, 7-days-a-week within the defined service area. The majority

of existing service patrols operate peak periods of 5:00 a.m. and 10:00 p.m. on

weekdays, or during special events. These programs typically have focused on

the highest congestion periods and the times with the highest crash rates.

However, this focus can leave large portions of the traveling public unserved

during nonpeak hours and can sometimes be confusing for motorists expecting

service during a disablement. The 24 hours, 7-days-a-week availability of FFSP

resources will ensure that traffic incident responders can promptly and

effectively manage emergency incidents occurring on roadways regardless of time

of day or day of week.

If 24 hours, 7-days-a-week service cannot be achieved because of resource

limitations or other constraints, an agency should assess the service hours

carefully in relation to crashes, severe crashes, and recurring congestion

periods and deploy the service across the most crucial hours. The agency should

also identify what additional funding resources would be required to provide 24

hours, 7-days-a-week service and determine whether those additional resources

are obtainable. Another option is for agencies to develop an on-call system to

provide services during major incidents that occur outside normal operating

hours.

4.3.2 Service Area

From a macro perspective and consistent with the Congestion Initiative,

FFSPs should be provided in each of the top 40 urban areas of the U.S. From a State, regional, or local

perspective, the FFSP service area should be clearly defined and communicated

to stakeholders and the public. Determining the service area is based on traffic

volumes, recurring congestion areas, number of traffic incidents, calls for

service, and crash frequency. The service area should focus on high traffic

volume corridors that experience a high number of traffic incidents that increase

the magnitude of congestion. Another factor in determining the service patrol

service area is the absence of freeway shoulders where hazards are exacerbated

when crashes or stalled vehicles occur. An example of this situation is a

bridge or tunnel with limited shoulders.

4.3.3 Frequency of Coverage

The frequency of coverage is a function of the total miles patrolled in the

service area and the number of FFSP vehicles traveling the area at a given

time. Existing programs have a patrol frequency over each segment that ranges

from every 10 minutes to 1 hour. The frequency of patrols provided should

support adopted performance goals. A common TIM performance measure is incident

clearance. For example, several states have 90-minute incident clearance goals.

Alternatively, performance goals can be categorized by incident severity. In

Utah, for example, minor fender-benders have a 30-minute clearance goal while

injury crashes are 60 minutes. An FFSP program should continually patrol the

service area at a frequency that supports the performance goal and can

realistically detect and clear an incident within the clearance goal.

4.3.4 Guidelines for Developing Vehicle Requirements

Since one of the primary objectives of an FFSP is quickly clearing vehicles,

the service patrol vehicle should be capable of, or designed for, towing

vehicles. These vehicles should be flat bed models; be specially designed and

equipped with a tow sling, tow bar, tow plate or wheel lift apparatus, attached

to the rear of the vehicle; or have a crane or hoist that is attached to the

bed or frame of the vehicle. The vehicle should meet State vehicle code

requirements for light-duty tow trucks to perform accident recovery work and

have all necessary permits to operate the service. The gross vehicle weight

rating should be at least 10,000 pounds and have a manufacturer rating of one

ton or more. The FFSP vehicle capabilities are identified so that an automobile

or light truck that presents a hazard on the roadway may be moved carefully and

quickly to a safe location. This service does not provide a tow to a garage or

repair station. Quickly removing the vehicle from the incident area will

restore the roadway to its full capacity and reduce the risk of secondary

crashes. Motorists can choose a private towing company to move their vehicles

from the safe location to a service station for repair.

Requirements for FFSP vehicles should be developed depending on the needs of

the particular region. Guidelines and considerations for developing these

requirements include:

- Storage

facilities for FFSP vehicles and equipment

- Four-speed

transmission or equivalent

- Power-assisted

service brake system

- Parking

brake system

- Dual rear wheels and tires

- Crane specification – boom capacity of at least 4 tons

- Car carrier specification (if used) – bed assembly of at least 3/16-inch

steel plate and at least 15 feet in length and 7 feet in width

- Push

bumper

- Identification

markings

- Amber

warning lights and lamps; no red lights should be visible

- Work

lamps

- Portable

tail, stop and signal lamps

- Reflectors

- Splash

guards

- Attachment

chains.

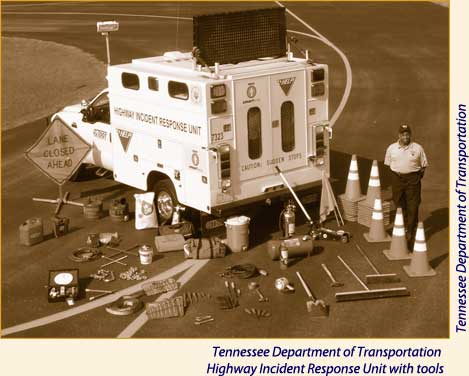

4.3.5 Guidelines for Developing Equipment Requirements

To assist motorists with minor vehicle disablements and to provide emergency

TTC at incident scenes, FFSP vehicles should be equipped with an assortment of

tools and supplies to support key functions.

The following is a recommended list of equipment and supplies to carry on the FFSP vehicle:

- Communications

- Two-way

radio

- CB

radio

- Law

enforcement radio

- Public

address system

- Cellular

telephone

- Mechanical

- Air

compressor

- Car

jack

- Power-operated

winch

- Tools

- Booster

cables

- Tire

gauges

- Wrench

sets

- Socket

sets

- Hammers

- Screwdrivers

- Pliers

- Wire

cutters

- Pry

bars

- Brooms

- Shovels

- Flashlights

- Electrical

multimeters/wiring testers

- Fluids

- Gasoline

- Oil

- Transmission

fluid

- Starter

fluid

- Water

- Anti-freeze

- Supplies

- Electrical

tape

- Duct

tape

- Wire

- Absorbent

material

- Hand

cleaner

- Paper

towels

- Safety

- First-aid

kit

- Fire

extinguisher

- Gloves

- Safety

goggles

- HAZMAT

guide book

- Traffic

Control

- Vehicle-mounted

variable message or arrow sign

- Cones

- Flares

- Traffic

control signs

Another piece of important equipment for an FFSP is identifiable uniforms

for operators. A uniform will establish confidence from other TIM responders,

law enforcement, and the public that the operator is an authorized official or

representative of the agency. Operators should also be equipped with an

official, openly displayed credential to show to motorists who are hesitant or

fearful to accept the services of an FFSP.

4.3.6 FFSP Operator Visibility Requirements and Apparel

The FHWA has established a rule in Title 23 of the Code of Federal

Regulations (CFR) titled, “Part 634 Worker Visibility.” The rule requires that all workers

within the right-of-way of a Federal-aid highway wear high-visibility safety

apparel when they are exposed either to traffic (vehicles using the highway for

purposes of travel) or to construction equipment within the work area. The rule

defines workers as people on foot whose duties place them within the

right-of-way of a Federal-aid highway. This worker definition encompasses all first

responders, including FFSP operators. Part 634 also defines high-visibility safety apparel as personal

protective safety clothing that is intended to provide conspicuity during

daytime and nighttime usage, and that meets the Performance Class 2 or 3

requirements of ANSI/ISEA 107-2004. ANSI/ISEA 107-2004 is the American National Standard for Highway

Visibility Safety Apparel and Headwear. This standard provides uniform guidelines

for the design and use of high-visibility safety apparel such as safety vests,

rainwear, outerwear, trousers, and headwear to improve worker visibility during

the day, in low-light conditions, and at night. ANSI/ISEA 207-2006 is the

American National Standard for High-Visibility Public Safety vests. This

standard establishes design and use criteria for vests to make public safety

workers highly visible to motorists.

4.3.7 Procedural Development Guidelines

Each agency has unique procedures and techniques that will require

clarification in operating an FFSP. An agency should develop procedural and

operational guidelines to clarify and document those preferences and establish

a baseline performance expectation so that all operators provide a uniform and

consistent service. The guideline will also provide stakeholder agencies with a

clear illustration of the FFSP-provided services and how interactions between

the agencies and the FFSP will occur. For a privately contracted service, the

operational guidelines should be used as part of the contract documents.

Guidelines should cover the following FFSP topics:

-

Mission, objectives, roles, priorities, and functions of the program

- Contract provisions

- Operational procedures

- Duties job description, conduct

- Response priorities

- Routes, vehicle positioning, staging, leaving a scene

- Dispatching

- Communications

- Safety

- Emergency TTC

- Dealing with motorists

- Dealing with motor clubs and towing companies

- Relationships with the TMC and stakeholders

-

Safety and response procedures

- Disabled vehicles

- Abandoned vehicles

- Relocating vehicles

- Traffic crashes

- HAZMAT

- Vehicle fires

- Debris removal

- Weather

- Construction

- Applicable laws, administrative policies, agreements

- Open roads policy

- Move it law

- Liability

- ICS

- Emergency operations plans

- Evacuation

- Interagency cooperation, commitments, and relationships

- FFSP policies

- Facility

- Shift change

- Phones

- Parking

- Ride-along

- Record keeping.

4.3.8 Initial Operator Qualifications

One of the biggest challenges that FFSP programs face is driver rotation and

turnover. Large driver turnover rates will increase costs to the program as it

increases the amount of time devoted to driver training and reduces the time

drivers are operating a vehicle on the program’s service routes. FFSP programs

can reduce driver turnover and overall program cost by paying competitive wages

and hiring qualified and skilled drivers. In many cases, skills will need to be

developed through training programs; however, drivers may already have some important

skills if they have previous background in towing, automobile repair, emergency

medical services, or highway maintenance. Hiring individuals with existing

skills in automobile repair or EMS may be cost probative since these candidates

may command salaries outside the FFSP program’s budget.

Initially, drivers should have the following minimum qualifications:

- 18

years of age

- High

school diploma or General Equivalency Diploma (GED)

- Clean

criminal background

- Applicable

Commercial Driver License (CDL)

- Clean

driving record

- Ability

to work independently

- Ability

to lift 50 pounds.

4.3.9 Operator Certifications and Training

After the initial hiring, an FFSP program should require and provide

training for patrol operators before they begin service. Training should

involve a combination of classroom style and on-the-job training to demonstrate

and describe the typical functions, responses, and services that the operator

will be providing. As a guideline, the program should provide annual refresher

training to emphasize new policies, procedures, or performance concerns. Common

training elements include:

- TIM

program overview, goals, and objectives

- FFSP

operating guidelines

- Vehicle

and equipment use and maintenance

- Safety

policies

- Radio

and communication procedures

- Defensive

driving

- Ride-along

with multiple shifts

- First

aid

- CPR

- Public

relations/customer service

- Maintenance

of traffic/emergency TTC

- Vehicle

recovery procedures

- Work

site protection

- Extinguishing

vehicles fires

- Minor

vehicle repair

- ICS

consistent with NIMS

- Disaster

preparedness/evacuations

- HAZMAT

response including the Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response

Standard (HAZWOPER) administered by the Occupational Safety and Health

Administration (OSHA).

Depending on the operational policies and the overall goals of the FFSP

program, the following formal certifications may further develop highly skilled

and trained operators. These certifications typically require ongoing refresher

courses and tests, and can be used to train drivers externally rather than

relying on internally developed training materials:

- International

Municipal Signal Association (IMSA), Work Zone Traffic Control Safety

- American

Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA), Traffic Control Technician

- Red

Cross, First Aid

- Red

Cross, CPR

- Department

of Homeland Security, Highway Watch

- Wreckmaster,

Towing and Recovery Operations Specialist

- National

Automotive Technicians Education Foundation, National Certified Automotive

Technician

- State

certified, Emergency Medical Technician

- State

certified, Fire Fighter

- State

certified, Animal Control Officer

- Federal

Emergency Management Association, National Incident Management System ICS-100

- Federal

Emergency Management Association, National Incident Management System ICS-200

4.3.10 Costs

As previously mentioned, the size of the program and operational policies

will drive the overall cost and annual budget. Existing service patrol programs

using private contractors range in cost per service hour from $35 to $98,

depending on the area and service vehicle used. Individual factors that

influence the overall program cost include:

- Operator

wages

- Operator

benefits

- Operator

training and certifications

- Vehicle

procurement

- Vehicle

maintenance

- Fuel

- Equipment

procurement

- Equipment

maintenance and replenishment

- Administrative

cost.

4.3.11 Communications and Dispatching

FFSP communications and dispatching should be closely integrated with TMC

operations. This is best accomplished with two-way radios, but cellular telephones

can also be used as a communication tool. Although an FFSP is routinely

patrolling the highway system, it is not reasonable to expect that the patrol

vehicle will detect all incidents. Some incidents will be detected by law

enforcement, TMC operators, or by other motorists reporting an incident to a

911 operator. As a result, the FFSP operator will typically rely on a

dispatcher to report incident locations and details to aid in quicker response.

In turn, the FFSP dispatcher will need close and convenient communications with

the TMC operators and with public safety and 911 operators. Depending on the anticipated

workloads of the TMC and public safety operators, these individuals could also

serve as the FFSP dispatcher.

Consistent with NIMS/ICS protocol, using common plain language is preferred

when communicating between the operator and dispatcher and between operators.

Communications should be limited to incident-related details and focus on the

who, what, and where of the incident. When the FFSP operator has direct linkage

to the TMC, incident situations and impacts such as lane closures can be

disseminated quickly onto DMS to provide real-time traveler information and

safety messages to motorists approaching the incident.

The close coordination required between the FFSP operator and

law-enforcement agency personnel requires two-way communications with law

enforcement. This requirement can be fulfilled by having the FFSP operator

carry a law enforcement radio. The radio may be preprogrammed with only car-to-car

channels to allow the FFSP to listen to information relayed about highway

incidents but eliminate law enforcement concerns about private communication.

More importantly, it will allow the FFSP operator to have on-scene

communications with law enforcement personnel to coordinate emergency TTC with

on-scene law enforcement officers to coordinate traffic flows and emergency

TTC. The law enforcement officer may require a shift in the emergency TTC or

may want to indicate that the scene is clear and the roadway should be opened

to traffic. When the incident scene is large, personnel may be spread out over

an extended area, and the emergency TTC may be set for an extended period of

time. Consequently, communications may not be as efficient for both parties

without two-way radios.

To further aid in communication, the FFSP cellular telephone should be

preprogrammed with important telephone numbers of potential responding

agencies, emergency management personnel, local transportation personnel,

on-call supervisors, and managers.

4.3.12 Automatic Vehicle Location

As an option, the FFSP vehicles may be equipped with an AVL system to help

inform dispatchers of the FFSP vehicle location, status, and speed. This

information can help dispatchers identify the closest and most appropriate FFSP

vehicle to respond to an incident location.

4.3.13 Record Keeping

FFSP activity should be well-documented to help identify total assist

records, driver performance, quality control, and incident reviews. The

information used to establish performance measures will help support funding

and provide key information to decision-makers.

Each FFSP operator should have log sheets and document information related

to each assist and incident. The following information should be recorded on an

activity/log sheet:

- Dispatch

time

- Arrival

time

- Departure

time

- Incident

type or nature

- Location

(mile marker, cross street, or landmark)

- Vehicle

identification number

- License

plate number and state

- Vehicle

make

- Vehicle

model

- Vehicle

year

- Vehicle

color

- Services

rendered.

Another alternative is for operators to use laptop computers similar to a

law enforcement mobile data terminal to record logs and transmit the activity

to a central database. These systems can be set up to transmit the data in

real-time and catalog entries without manual data entry.

FFSP managers should place activity logs into a database to document and

record overall program statistics. This information can be used to create

annual reports, determine trends in activity, determine activity in specific

service areas, and provide valuable information about the performance of the

overall program.

Another FFSP program record-keeping activity involves reviewing and logging

comment cards received from assisted motorists. This information can be used to

support funding, gauge public support for the service, and assess driver

performance. The comment cards require no return postage and request basic

information: the name and contact information of the assisted motorist; the

services provided to the motorist; the day, time, and location of the assist;

the general performance of the FFSP operator; and room for general comments.

4.3.14 Emergency Temporary Traffic Control

The vast majority of traffic control operations that FFSPs provide are in

emergency or short-term situations in response to traffic incidents. MUTCD

Chapters 6G and 6I address controlling traffic for TTC zone activities and

incident management areas. Because major incident durations may exceed more

than 1 hour and FFSP operations may extend into nighttime hours, the MUTCD

requires using retroreflective and illuminated devices.

The MUTCD Chapter 6I states that, “

The primary functions of TTC at a

traffic incident management area are to move road users reasonably safely and

expeditiously past or around the traffic incident, to reduce the likelihood of

secondary traffic crashes, and to preclude unnecessary use of the surrounding

local road system.” FFSP operators should be trained in safe practices for

accomplishing TTC. At incident

scenes, FFSP operators should also:

- Be

aware of their own visibility to oncoming traffic

- Move

traffic incidents as far off the traveled roadway as possible

- Provide

appropriate warning to oncoming traffic

- Estimate

the magnitude and duration of the traffic incident

- Estimate

the expected vehicle queue length

- Set

up appropriate TTC.

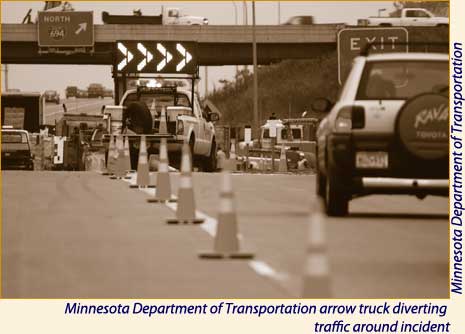

As guidance, the MUTCD states that warning and guide signs used for TTC

incident management situations may have a black legend and border with a

fluorescent pink background. As a basic guideline, the FFSP should carry a

truck-mounted arrow board, retroreflective cones, flares, and retroreflective

signs to set up short-term emergency shoulder or lane closures.

In emergency situations, the FFSP should use “on-hand” TTC devices for the

initial response, and the TTC devices should not create an additional hazard.

Typical applications of TTC are found in the MUTCD’s Chapter 6H and represent a

variety of conditions used for temporary work zones and maintenance operations.

It is not reasonable to expect the FFSP to be able to store and carry the types

and numbers of TTC devices (such as barriers, barrels, flashers, signs, and

arrow panels). These devices may be required for a longer-term situation on a

high-volume, high-speed facility to set up appropriate advance warnings,

tapers, or closures within the traveled way to provide an appropriate TIM responder

work space. Many of the TTC applications for shoulder, lane, etc., closures in

Chapter 6H can be emulated for long-term major incidents, but are not

reasonable for shorter-term emergency situations because the set up time of the

TTC will take longer than the clearance time of the incident. Because of the

number and types of devices required for intermediate- or long-term closures,

an FFSP should consider contacting department of transportation maintenance or

other traffic control support personnel to set up TTC that is more appropriate

for major incidents that generate longer vehicle queues. FFSP should seek

additional TTC assistance for traffic incidents that have durations estimated

as greater than 2 hours.

4.3.15 Suggested Emergency Traffic Control Procedures

4.3.15.1 Vehicle Placement

When the FFSP first arrives at a scene, the vehicle should be positioned to

protect the incident scene and prevent additional crashes. Using warning lights

and, if available, a dynamic message or arrow sign, will help establish better

visibility of the FFSP vehicle. After assessing the scene, establishing the

appropriate response, and arranging for appropriate emergency services if

needed, the FFSP should implement the on-hand traffic control devices. In cases

where no injuries have occurred and the vehicle can be moved, at the direction

of law enforcement, the FFSP should mark the vehicle(s) final resting positions

for future traffic crash investigation and relocate the vehicle to the shoulder

or another safe area.

When the FFSP is a secondary responder, similar procedures are followed, but

the FFSP operator should report to the Incident Commander (IC) and assess the

situation to determine the appropriate TTC procedures.

When the FFSP is a secondary responder, similar procedures are followed, but

the FFSP operator should report to the Incident Commander (IC) and assess the

situation to determine the appropriate TTC procedures.

In most situations such as a shoulder assist or when a lane is blocked, the

FFSP should position the vehicle about two or three car lengths behind the site

and at a location that provides adequate visibility and warning to approaching

vehicles. The FFSP should take extra care not to block emergency vehicles from

maneuvering in, around, or away from the incident scene. As part of an FFSP

program, basic diagrams should be developed to illustrate the preferred

placement of the vehicle to be consistent with procedures and preferences of

TIM responder and law enforcement agencies.

4.3.15.2 Emergency Lights, Arrow Boards, Cones, and Signs

MUTCD Section 6I.05 supports using emergency vehicle lighting as an

essential action for the safety of TIM responders and persons involved in the

traffic incident. However, emergency lighting should only be considered as a

warning because it does not provide positive and effective traffic control.

Furthermore, emergency lights at night can often confuse and distract

motorists. If effective positive traffic control is established with

appropriate traffic control devices, the use of emergency lights can be reduced.

When appropriate, forward-facing emergency lights should be turned off once on

scene. Despite the guidance provided by the MUTCD, a vehicle with emergency

lights is commonly considered a traffic control device; however, a more

effective and positive traffic control procedure is to use a truck-mounted

dynamic message or arrow sign. A dynamic message or arrow sign aids in

communicating the direction road users need to take to maneuver around the

incident scene more safely and expeditiously. Using on-hand cones and signs can

provide additional advance warning, tapers, and positive traffic control in

advance of the FFSP vehicle and around the incident scene. Typically, an arrow

will indicate a positive direction away from a blocked lane while a straight line

or caution mode would indicate a shoulder closure.

When a lane is closed, vehicles in the blocked lane will need to merge with

adjacent lanes, causing disruption. Cones placed several hundred feet upstream

of the FFSP vehicle and incident scene can help move this traffic disruption

away from the immediate scene and away from TIM responders, the FFSP, and

persons involved in the incident. Traffic cones placed in a taper alignment

also help to provide positive TTC to motorists to maneuver around the scene

safely and expeditiously. In combination with traffic cones, placing warning

signs will also help emphasize the closure, provide positive guidance to

motorists, and secure the incident scene. Correctly placing cones and TTC

devices is critical in providing motorists sufficient visibility and warning to

react without creating a danger to other traffic, to TIM responders at the

scene, and to the scene itself.

After the appropriate TTC devices have been placed, the FFSP should

determine the value of providing additional positive manual traffic control at

the scene by flagging traffic around the scene. The FFSP should be trained and

qualified to provide flagging operations.

In addition to the incident scene itself, the FFSP operators should pay

attention to the back of the queue. If possible, more TTC or FFSP vehicles can

be positioned in advance of the back of the queue to provide advanced warning

to approaching vehicles. This action helps prevent secondary crashes.

4.3.15.3 Typical Emergency Traffic Control Plans

An FFSP operator should be trained and capable of quickly and safely setting

up the emergency TTC for traffic incident scenes likely to be encountered. An

FFSP should develop typical diagrams to illustrate the preferred placement of

vehicles, cones, signs, arrow boards, and flagging operations in relation to

the incident scene. The following list of typical incident situations should be

used as a guide to develop local procedures for TTC:

- Disabled

vehicle on shoulder/shoulder assist

- Single

lane closure (right or left lane)

- Center

lane blocked

- Two

lanes blocked

- All

lanes blocked

- All

lanes blocked with detour.

To quickly set up these typical closures, the FFSP should be equipped with

the following:

- Truck-mounted

dynamic message or arrow sign

- Minimum

of 16 retroreflective traffic cones

- Flares

- Flags

for flagging operations

- Retroreflective

traffic vests.

- If

space is available on the FFSP vehicle, it would assist in providing positive

traffic control by having several traffic incident management area signs as

illustrated in the MUTCD, Figure 6I-1.

4.3.16 National Incident Management System / Incident Command System

The FFSP should follow the NIMS and use the ICS for activities associated

with traffic incidents. The National Fire Service IMS Consortium published the Model

Procedures Guide for Highway Incidents, which offers an initial design

document in which an FFSP agency can work with other regional organizations to

develop and build on joint operating procedures. The procedures should apply to

routine incidents and large, complicated, and unexpected major disasters. The

FHWA has also published the Simplified Guide to the Incident Command System

for Transportation Professionals. This guide introduces ICS to those who

must provide specific expertise, aid or material during highway incidents but

who may be unfamiliar with ICS organization and operations. FFSP operators, supervisors, managers,

and administrators should be trained in using NIMS, the organizational

structure, and the unified approach concept at the core of the command and

management system. The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) NIMS

provides a template for governments to work together to prepare for, prevent,

respond to, recover from, and mitigate the effects of incidents.

Under ICS, the IC is responsible for managing all incident operations. The

first arriving unit assumes command and identifies an IC until a higher ranking

officer arrives on scene and assumes command. As such, if an FFSP is the first

arriving unit, it should assume command. Upon arrival, the law enforcement or

other TIM responder will typically assume command. The transfer of command is

announced and the former IC is reassigned to other responsibilities. Typical

responsibilities assigned to the FFSP will be traffic control duties in support

of the incident operations. When the FFSP responds to an incident as a

secondary responder (e.g., not the first arriving unit), the FFSP should follow

standard procedures in arriving at the scene and then report to the IC.

The organizational structure of ICS is modular in nature and can expand as

the complexity of the incident escalates. In more complex cases, sections and

branches may be implemented within the command organization structure, and the

FFSP may find itself reporting to a Section Chief or Branch Director rather

than directly to the IC. An FFSP operator should be prepared to be a group

leader assigned to a specific functional assignment. In most cases, the

assignment will be traffic control in and around the incident scene or on

emergency alternate routes for diverted traffic. In complex or longer duration

incidents, the FFSP operator should be prepared to elevate the situation to a

supervisor or manager and be prepared to request, organize, and assemble additional

traffic control resources.

4.3.17 Program Performance Monitoring

Measuring program performance is a critical step in monitoring its progress

and overall success. It is also critical to measure the program so agencies can

communicate the benefits and successes of the program to decision-makers,

policy-makers, sponsoring agencies, and the public.

FFSP programs should gather and record data about the number and type of

services that each service patrol operator delivers. In this manner,

statistical analysis can be used to develop trends and comparisons about service

areas, service hours, types of services rendered, times of the year, etc. When

tracked properly and linked with a dispatch center such as a TMC, statistics

should also be kept about response times, incident durations, incident

clearance times, lane blockages, and incident severity. This data will help

identify the program performance relative to its impact on quick clearance and

congestion. Lastly, the condition of the FFSP vehicles should also be monitored

by monthly inspections and data collected about vehicle miles, maintenance

needs, fuel efficiency, and equipment used.

The agency can use the compiled program data to evaluate its performance and

identify performance gaps. This data can also be used to quantify the benefit

relative to its cost in bolstering support for its continued or expanded

funding.

A basic, but important, way to monitor and track program performance is by

using comment cards/survey forms. At the end of each service call, an FFSP

should provide the assisted motorist with a self-addressed, stamped feedback/

survey card. The FFSP should maintain a record of the returned cards to gauge

and track customer satisfaction with the program. Motorists’ comments and

suggestions can be used as supporting documentation concerning the benefits of

the FFSP program and can also be used to evaluate individual drivers. Negative

comments about FFSP drivers should be investigated and, if found to be valid,

result in performance reviews, warnings, suspensions, and dismissals if

continued negative reviews are received. The survey responses should also be

used to award drivers for superior performance. In addition to citizen

feedback, driver performance should also be tracked based on monthly inspections,

crash history, and number of service calls performed.

4.4 Modes of Operation

4.4.1 Disaster Preparedness

Section 4.1 discussed the standard day-to-day operational FFSP objectives.

While current programs have different procedures and policies in place for responding

to natural disasters, an FFSP should be a key component of a region’s overall

emergency response plan relative to traffic control assistance within the

framework of the NIMS/ICS. For example, a disaster happens and an evacuation

route is implemented so keeping the route cleared of incidents becomes even

more critical than during the FFSP’s standard operating hours.

In the case of a disaster, natural or otherwise, the FFSP should maintain

its overall operational objectives and perform its normal services to keep

highway traffic moving. As part of a region’s overall plan, the FFSP should be

prepared to:

- Perform

its normal services along an evacuation route

- May

require expanding the FFSP program service area

- Assist

motorists with fuel, water, and minor repairs along an evacuation route

- Add

vehicles to facilitate traffic control

- Assist

highway patrols and public safety

- Implement

alternate route or emergency detour plans

- Assist

with contra flow traffic operations

- Block

roadway entrance and exit ramps

- Assist

with equipment support and equipment routing

- Manually

operate traffic signals.

4.4.2 Planned Special Events

Similarly, FFSP programs can facilitate traffic control and clear incidents

for planned special events. This approach may require the program to expand its

service area and service hours to provide assistance during the event.

4.5 User Involvement, Interaction, Roles, and Responsibilities

FFSPs have contact and interact with many users on the highway system.

During normal operations or major unexpected incidents, an FFSP will interact

with TIM responders from law enforcement, fire and rescue, EMS, departments of

transportation, towing and recovery companies, the media, public information

officials, travelers, and road users. Section 2.3 detailed these interactions.

In an ideal situation, an FFSP is a major component of an ongoing, sustained

TIM program. In this context, FFSPs should be regular participants in incident

debriefs and after-action reviews. Also, a TIM program can serve as the

foundation for building relationships between stakeholder agencies involved in

highway incident response and interactions with an FFSP. Other key FFSP interactions

are its communication with a regional TMC and its integration within defined

procedural guidelines of a regional TIM program. The following list explains

the general roles and responsibilities of FFSP users. Note that some roles and

responsibilities can be combined into one overall position.

-

FFSP

Operator (Driver) – Serves as the frontline contact to deliver the services,

activities, and functions of an FFSP. Operates the vehicle, patrols the

highways, coordinates with other on-scene TIM responders, and provides service

and assistance to motorists.

-

FFSP

Dispatcher – Communicates incident information to the FFSP operators. Some of

this information is likely to be relayed from other sources such as law

enforcement personnel, other motorists, or the TMC operator.

-

TMC

Operator – Monitors and operates the traffic management system. Incident

information requiring an FFSP response is relayed to the FFSP dispatcher.

Similarly, the FFSP relays information to the TMC Operator who collects

traveler information and coordinates traffic management actions.

-

FFSP

Supervisor – Administers and develops operator schedules to deliver the

services across the prescribed service area and service hours. Supervises and

monitors daily operations. Provides quality control checks, provides operator

performance reviews, and is prepared to call-in additional operators for major

incidents. Maintains employee files, training records, and activity logs.

-

FFSP

Fleet Maintenance Manager – Administers and maintains the service patrol fleet

of vehicles. Can provide vehicle and equipment inspections.

-

FFSP

Trainer – Coordinates the implementation of operator orientation and training.

Ensures that each operator complies with the training and certification

requirements.

-

FFSP

Hiring Manager – Interviews candidates and ensures potential candidates meet minimum

qualifications. Ensures that agency hiring procedures are followed. Ensures

that necessary background checks are performed concerning driver and criminal

records.

-

FFSP

Manager – Supervises overall day-to-day operations and oversight of an FFSP.

Manages the FFSP vision, direction, goals, functional description, policy,

procedural guidelines, and performance. Key participant in the overall

integration of an FFSP into a comprehensive TIM program. Establishes and

maintains partnership agreements with stakeholder agencies about operational

guidelines. If the FFSP is contracted to a private operator, this position is

likely to remain staffed by the funding agency to oversee contractual obligations

and overall program performance.

-

Law

Enforcement and Emergency Services – Works closely with law enforcement and

emergency services to assist them in making the incident scene safe and

provides positive TTC to move motorists expeditiously around the incident. Responds and assumes command of the

scene when property damage and injuries have occurred. FFSPs should be prepared

to implement emergency TTC activities as part of the overall scene management,

but also provide the IC updates about the status of activities and suggestions

for keeping traffic moving.

-

Towing

and Recovery – Required in cases where the FFSP is not able to remove vehicles

from the traveled way to a safe area. Most regions have a rotating list of

pre-qualified towing companies for specific service areas. Transportation or

law enforcement agencies maintain these lists, and the FFSP should contact

these agencies to dispatch the towing agency when appropriate.

-

All

FFSP operators and personnel shall display professional and courteous conduct

at all times. The FFSP should not accept gratuities or fees for services

rendered to motorists. FFSPs should have procedures to handle FFSP cell phone

use by motorists and guidance for transporting motorists.

4.6 Support Environment

A department of transportation, a law enforcement agency, or a privately

contracted service with a private corporation can operate an FFSP. Regardless

of the administrative mechanism for operating the FFSP, a support environment

will need to be created and maintained to ensure continued overall success.

-

Funding – Identifying the funding sources and programming money to meet anticipated

capital and operations costs is fundamental to starting, sustaining, or

enhancing a program. Section 4.2

provides guidelines for funding sources and overcoming this constraint.

-

Oversight – FFSP oversight responsibility can vary depending on the agency leading the

program and the unique organizational structure of that agency. Nonetheless,

FFSP Manager oversight will be required for an in-house or contracted service.

As part of the oversight support environment, a clear set of goals, performance

measures, procedural guidelines, training requirements, and operator

qualifications should be established to ensure sustainability and consistency

of the FFSP. Section 4.3.7 contains suggested procedural guidelines and

performance measures.

-

Facilities,

Equipment, and Maintenance – An agency operating an FFSP should anticipate

ongoing operational costs related to the maintenance and replacement of

vehicles and equipment. Section 4.3.4 addresses the vehicle and equipment

guidelines.

-

Communications – Another fundamental support system for an FFSP is the communications link

between the FFSP operator/driver and dispatcher, TMC operator, law enforcement

personnel, or other TIM responder agency. Section 4.3.11 details the two-way

radios, cellular telephones, and computer-aided-dispatch system for FFSP

communications.

-

Partnerships – An FFSP will have many interactions with other stakeholder agencies when

responding to highway incidents. These agencies are instrumental in keeping

highway traffic moving and incident-free to fight congestion. An FFSP will be

more successful when it has the collaborative support of law enforcement and

TIM responder agencies. This support environment can be formalized with a

partnering agreement, MOU, or even a mutual aid agreement. Section 2.4.7

discusses these interactions.

-

Contracting

Mechanism – When a private company provides services on behalf of an agency

sponsoring the program, the sponsoring agency will need to solicit and procure

services through a binding contract. When developing a specific contract, the

focus should be on the type of services required, goals of the program,

procedural guidelines, service area, service hours, operator and company

qualifications, experience, training, interaction with stakeholder agencies,

and equipment maintenance and replacement.

-

Outreach – A basic form of outreach is to provide assisted motorists with a comment card

or brochure. This method provides direct contacts with more information on the

service and obtains feedback from those the FFSP directly affects. With much

variation between programs in the U.S. and to a lesser extent within a region,

motorists may be easily confused by the types of services to expect, when

services are provided, and on the congestion relief benefit gained from the

program. An FFSP should develop and implement an outreach and public

information campaign to make the public aware of the program. The more aware

the public is about the program service and its benefits, the more likely the

public is to voice support and influence decision-makers to identify funding

sources for an FFSP.

4.7 Incremental Priorities

As discussed in Section 4.2, overcoming the constraints would largely be

attributed to having more funding available to the FFSP program. Assuming the

existing program already provides the basic services, additional funding will

be used on the following priorities to evolve incrementally into an FFSP over

time:

- Expand

service area, increase

mileage, add routes

- Incorporate

all freeway or turnpike miles

- Increase

support to major arterials

- Expand

service hours in existing operational service areas

- Increase

the total service hours of operation

- Add

shoulders of peak periods

- Implement

a night or weekend shift

- Operate

24 hours, 7-days-a-week

- Additional

operator capabilities and pay levels

- Improve

operator qualifications, training, certifications, and pay levels (see Sections

4.3.7 and 4.3.8)

- Provide

advancement opportunities for personnel

- Improved

skill and education levels

- Increase

number of positions for additional operators and mechanics

- Update

fleet and equipment

- Improve

fleet equipment

- Improve

radio communication

- Increase

patrol frequency

- Increase

service for an existing patrol area to reduce time for incident detection and

clearance

- Other

priorities

- Establish

outreach and marketing programs

- Establish

regional TIM teams to support local programs.

July 9, 2008

Publication #FHWA-HOP-08-031