1 INTRODUCTION

Evacuations occur for countless reasons under many different circumstances. A jurisdiction may need to evacuate one block of office buildings (water-main break), a neighborhood (forest fire), a major portion of the downtown area (terrorist attack), or even an entire city (earthquake or hurricane). While successful evacuations are always difficult to execute due to the level of coordination required among agencies and jurisdictions, this challenge becomes magnified during a little- or no-notice evacuation. No-notice incidents can be either small-scale or wide-scale and can happen anywhere at any time. After a no-notice incident, responders will have a very limited window of opportunity to prepare before an evacuation begins.

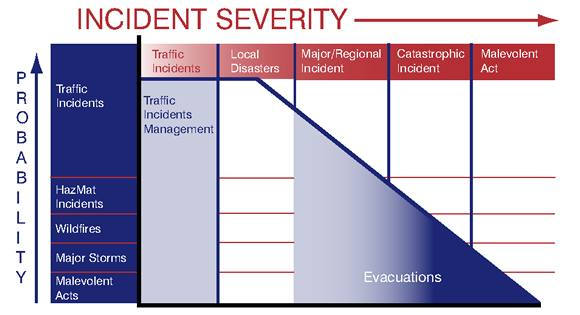

A U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) study1 concluded that evacuations of 1,000 or more people occur approximately every two to three weeks. Focusing on a 12-year period, the study determined that most evacuations resulted from natural disasters (58%), particularly wildfire threats to populated areas; technical disasters (36%), including fixed site and transportation-related industrial accidents; and malevolent acts (6%), including terrorist attacks. Combine these larger-scale evacuations with much more frequent small-scale ones, and it becomes clear that evacuations, varying in scope and probability, occur on an almost-daily basis. As such, experience and expertise in evacuations occur not primarily at the Federal or State levels of government, but at the local level, as shown in Figure 1.1.

To be prepared for evacuations in this environment, transportation agencies must work with emergency management officials on evacuation planning efforts. This coordination must occur during the planning phase since there will be little time to plan for a response in the little- or no-notice environment. Any type of incident resulting in an evacuation will both rely on and have an impact on the transportation system and resources of jurisdictions. Except for rare instances when citizens are advised to shelter in place, affected populations may have to be moved out of harm's way to a safer location following a little- or no-notice incident. Whether this movement is done by foot, public transportation, or via personal vehicles, the transportation infrastructure will play a critical role during the evacuation. In addition, first responders must maintain the ability to respond to the incident and to transport the ill and injured to medical facilities; this capability relies in large part on the availability of the transportation network. Regardless of the reason for or scale of the evacuation, an effective evacuation depends upon the capacity of the transportation network and the cooperation of transportation agencies' management and staff.

PURPOSE

The Routes to Effective Evacuation Planning Primer series seeks to improve transportation officials' knowledge and capabilities with regard to evacuation planning and execution. By using these Primers, transportation officials and their staffs will be better prepared to participate with other agencies in the evacuation planning process, will have a clearer understanding of their roles during an evacuation, and will be able to support an evacuation more effectively.

This Primer provides ideas and considerations for transportation officials that are applicable across the scale of little- or no-notice evacuation incidents. It addresses the use of the highway system during evacuation operations following an incident that gives little to no warning and that allows for no advance planning. It provides information about planning techniques, strategies, and tactics that will prepare transportation agencies and their jurisdictions to respond effectively by implementing an evacuation on extremely short notice.

The contents of this Primer are based on the findings from numerous studies following major or catastrophic incidents where evacuations were ordered. The Primer identifies transportation technologies available to aid evacuation planners and operations staff in their attempts to make maximum use of the transportation network during emergencies. In addition, the Primer demonstrates ways to develop better evacuation plans through integration of transportation professionals in the process.

This Primer takes an "all-hazards" approach to evacuation planning. The concepts identified in the Primer series are applicable when dealing with both small and large evacuation incidents, regardless of the trigger that prompts the evacuation. The Primer should be one of many resources that officials use to build the best possible evacuation strategy for their jurisdictions.

INTENDED AUDIENCE

The information contained within this Primer is directed toward transportation officials, first responders, and emergency managers who will plan and execute evacuation efforts. Transportation agencies will have an integral role during an evacuation by acting in a support capacity to the comprehensive response coordinated by emergency management agencies and executed by first responders. Transportation officials, first responders, and emergency managers will benefit from a better understanding of what roles the transportation agencies, networks, and infrastructure can play during an evacuation. This understanding, combined with knowledge of particular transportation systems and resources, will enable officials to take a more proactive, participatory role during the planning process and to represent their agencies more effectively. The information in this Primer will also help transportation agencies' staffs identify the issues and challenges they should address during both the planning process and the execution of an evacuation.

Emergency management officials will also benefit from the information in this Primer. As the lead officials in coordinating evacuation planning and execution, emergency managers will rely in large part on transportation networks and operating systems. By gaining a better understanding of transportation-related issues, tools, and capabilities, emergency managers and their staffs will be able to better anticipate the benefits transportation systems are able to provide during an evacuation, as well as the transportation-specific issues that will need to be resolved. They will also gain an understanding of how to leverage investments that have already been made by transportation agencies (e.g., Intelligent Transportation Systems [ITSs] and Transportation Management Centers [TMCs]) to manage and mitigate congestion, which provide almost-real-time information and communication exchanges.

As those responsible for the execution of evacuations, first responders will gain an understanding of the support that transportation operations staff and capabilities can provide. First responders in many major urban areas are aware of the Department of Transportation (DOT) full-function service patrols2 used for incident management, but may not envision a role for them during evacuation operations. Service patrols, TMCs, and other transportation capabilities and assets can aid in making evacuations more efficient and safe, while helping safeguard firefighters and police involved in moving people out of harm's way. They can aid motorists who run out of gas or have mechanical problems, set up safety cones, provide information from traffic cameras, provide traveler information using the 511 system or dynamic message signs (DMSs) along the highway, and use traffic counters to monitor traffic flows on highways.

(Photo: John Blaustein. Available at http://www.mtc.ca.gov/news/transactions/ta04-0503/fsp.htm.)

NO-NOTICE EVACUATIONS

This Primer focuses on performing evacuation operations with little or no advance warning. Examples of incidents that might cause a no-notice evacuation include a hazardous materials spill due to a vehicular or train accident, an explosion at a chemical plant, a terrorist attack on some aspect of a jurisdiction's infrastructure, a flashflood, or even an earthquake.

Responses to an evacuation are organized by evacuation phases. The first Primer in this series, Using Highways During Evacuation Operations for Events with Advance Notice, outlines the phases for an advance notice evacuation: Readiness, Activation, Operations (two-tiered), and Return-to-Readiness, as shown in Figure 1.2.1. Figure 1.2.2 illustrates the operations cycle for a no-notice evacuation. While the phases remain the same, for no-notice evacuations there is either a very limited or a non-existent Readiness Phase.

A no-notice incident creates particularly challenging circumstances in which to carry out an evacuation. With an advance-notice evacuation, information becomes available during the Readiness Phase regarding the incident that has occurred and the factors that may require an evacuation. Decision makers have time to collect the information they need to determine whether an evacuation should be ordered and, if so, the best way to carry it out. With a no-notice incident, sufficient information is likely to be unavailable to decision makers before a determination has to be made on whether to order an evacuation. Instead, incomplete, imperfect, and, at times, contradictory information about the incident is arriving, if at all, at the same time decisions need to be made. This means decision makers must be prepared to act on limited information, and agency staff – particularly individuals located in TMCs and in the field – must be trained so that they can effectively respond rapidly and with imperfect information.

Imperfect information is problematic under normal circumstances. This is the case even more so with no-notice evacuations due to the quick response time required. In advance-notice evacuations, jurisdictions make decisions regarding the implementation of an evacuation to prevent lives from being put in imminent danger; in a no-notice scenario, citizens are usually already at risk. Decision makers have little or no time to wait for additional or better information in a no-notice scenario because any delay will likely have a significant effect on the safety of their citizens; they must be willing to make decisions with whatever information is available at the time.

What does this mean for transportation officials? From a transportation standpoint, during a no-notice evacuation transportation agencies will have to be in close contact with decision makers about which evacuation routes and traffic management tactics should be used. Decisions on which roads to use will be based on the capacity, safety, and potential chokepoints of those roads, among other factors described in this Primer. However, there is insufficient time during a no-notice incident to determine the capacity, safety, and potential chokepoints of all roadways under a transportation agency's jurisdiction; such information should already have been compiled and prepared for use. Preplanning, computer modeling, and responder training and exercising, all critical aspects, will be discussed in depth throughout the other sections of this Primer.

|

An advance-notice evacuation is really a preventative course of action while a no-notice evacuation is a response activity. |

PREPLANNING VS. ADVANCE PLANNING

For any agency/organization/jurisdiction that will have a role in a no-notice evacuation, preplanning is a necessary undertaking. It must not be done only once; the process and the findings need to be updated regularly. A general rule is to update plans on at least an annual basis. Plan reviews may also be required due to any changes in Federal, State, or local regulations that stipulate new or revised practices. As such, it is essential that the focus of a jurisdiction's evacuation plan is on preparedness and planning activities.

The most significant challenge posed by little- or no-notice evacuations is that they do not provide emergency managers, first-responders, and transportation personnel with the opportunity to prepare once it is known that an incident is impending but before the incident occurs. Focusing on what can be done ahead of time to prepare for a no-notice evacuation will mitigate the effects of not having a Readiness Phase or having an extremely limited Readiness Phase.

It is important to note the distinction between preplanning and advance planning. Preplanning refers to planning efforts undertaken by jurisdictions or agencies before they are aware that they need the information to make an operational decision. It is considered preplanning if transportation officials determine the capacity, safety and potential chokepoints of their transportation infrastructure so that if an incident ever occurs the information will be on hand to aid decision makers. Preplanning also includes periodic training for all levels of staff that would be involved in a response.

Jurisdictions accomplish advance planning during the Readiness Phase based on event- or incident-specific information. For example, a jurisdiction learns that there is the potential for a wildfire to break a fire line and move toward populated areas. Based on the incident, the geography and demographics of the area that might be affected, and other relevant factors such as the weather and location of roadways, a jurisdiction will do advance planning to determine the best course of action (shelter in place, evacuate, etc.). Much of the time, preplanning information will be used during the advance planning process.

| PREPLANNING |

| Planning efforts taken by an entity before it is aware that the information is required to make an operational decision |

| ADVANCE PLANNING |

| Planning done during the Readiness Phase based on incident-specific information |

PRIMER ORGANIZATION

This Primer is organized into six sections.

- Section1: Introduction

- Section 2: Planning Process – Focuses on the overall process used to develop an evacuation plan. Because many of the elements of creating an evacuation plan are covered in detail in the first Primer, Section 2 briefly touches upon these elements, concentrating on the critical role transportation officials will play.

- Section 3: Explanation of No-Notice Incidents – Defines no-notice incidents, describes the likely scales and consequences of the incidents, and provides examples.

- Section 4: Considerations in a No-Notice Context – Focuses on the unique issues and problems associated with no-notice incidents. This section highlights how and why no-notice evacuations require different strategies and tactics than an event with advance notice and demonstrates how these differences will affect transportation officials as they respond to a no-notice evacuation.

- Section 5: Planning Considerations – Lists the issues that need to be addressed as part of an evacuation plan capable of an effective response to a no-notice incident. Rather than describing each of the considerations (as covered in the first Primer on advance notice evacuations), this section explains how these factors will be affected by a little- or no-notice scenario and how the planning process should be modified to compensate for the no-notice factor.

- Section 6: Plan Elements – Provides checklists that are important to consider when preparing a plan for a no-notice evacuation. The checklists adopt an all-hazards approach and can be applied to any type of no-notice incident, whether natural or man-made.

| INCIDENT |

| An incident is an unexpected occurrence, caused by either human or natural phenomena, that requires response actions to prevent or minimize loss of life, or damage to property/the environment. |

| EVENT |

| An event is a planned, non-emergency activity, such as a parade, concert, or sporting event, which will include the activation of an ICS organization. |