Alternate Route Handbook

4. Alternate Route Selection

|

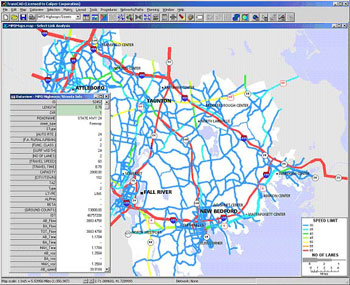

| Figure 4-1. Using a demand model in alternate route selection. |

INTRODUCTION

The first phase of alternate route planning is alternate route selection. Chapter 3 identified the following seven steps that must be completed in order to select alternate routes that facilitate improved corridor operations without creating undue impacts on the community:

- Determine objectives

- Establish alternate route criteria

- Assemble and index data

- Identify preliminary alternate routes

- Conduct preliminary alternate route site visit

- Evaluate preliminary alternate routes

- Select preferred alternate route

DETERMINE OBJECTIVES

The first step in the alternate route selection process is determining performance and community-based objectives to guide planning activities and the alternate route selection process. Stakeholders must agree on what objectives they want to meet in developing the alternate route plans. Considerations include:

- Local or regional

- Should the alternate route be geared toward local travelers who likely travel short distances along the main route and want to remain as close to the main route as possible?

- Should it be geared toward long-distance, regional travelers who desire an alternate route that provides the lowest travel time to the next major populated area or major interchange (e.g., between two freeway facilities), regardless of its proximity to the main route or what cities the route passes through?

- Should separate alternate routes be set up for local and regional travelers?

- Should the alternate route be geared toward local travelers who likely travel short distances along the main route and want to remain as close to the main route as possible?

- Geographical area

- What geographical area should the alternate route plan cover?

- Should it encompass a single freeway facility or only a single freeway segment?

- Should it consist of a series of plans for multiple facilities across a

metropolitan area? - Should it be a Statewide plan?

- Should it be coordinated with adjacent States, particularly if a metropolitan area crosses State lines?

- What geographical area should the alternate route plan cover?

- Alternate route facility types

- Should freeways, arterial streets, and/or multi-jurisdiction roadways be considered as preliminary alternate routes?

- Interagency coordination

- To what extent should the lead agency coordinate with other stakeholders?

- Should the lead agency coordinate with a State transportation/public works agency to use State roads or a local transportation/public works agency to use city streets as an alternate route?

- Should the lead agency coordinate with both State and local transportation agencies throughout the selection process?

- To what extent should the lead agency coordinate with other stakeholders?

- Frequency of alternate route implementation

- Will it be used only in the case of a complete closure of the primary route for a prolonged period?

- Will it be used whenever a lane closure occurs on the primary route during specific days and times?

- Will it be used only in the case of a complete closure of the primary route for a prolonged period?

In some cases, the objectives may change during the alternate route planning process. For example, the lead agency may initially intend to work alone, without much coordination with other agencies. However, while selecting an alternate route, the lead agency may determine that acceptable routes are under the jurisdiction of other agencies, thus requiring coordination with these agencies to effect optimal alternate route operation during diversion. Also, different stakeholders have different areas of expertise that may be useful in alternate route planning. For example, a transportation/public works agency may be the most knowledgeable about traffic conditions, while a law enforcement agency may be the most knowledgeable about safety problems.

Stakeholders involved in the selection process must coordinate their work efforts to facilitate a seamless and successful selection process. In most jurisdictions, the State DOT acts as the lead agency in the selection of the candidate and, after evaluation, the preferred alternate routes. In some jurisdictions, the State police may take the lead, or the State police and State DOT may co-lead.

ESTABLISH ALTERNATE ROUTE CRITERIA

After stakeholders identify the objectives, they may begin establishing alternate route criteria. Stakeholders must agree on what criteria alternate routes must meet before they may select the alternate route. Table 4-1 shows the stakeholders typically involved in establishing alternate route criteria and the roles they are likely to perform.

Table 4-1. Stakeholder involvement in establishing alternate route criteria

| STAKEHOLDER | ROLE |

|---|---|

| Transportation/public works agency |

|

| Law enforcement |

|

| Fire department |

|

| Emergency medical service |

|

| Transit agency |

|

| Turnpike/toll authority |

|

| Elected officials |

|

| Planning organization |

|

| Individuals and community groups |

|

Minimum Actions for Establishing Alternate Route Criteria

The task of establishing alternate route criteria involves the following minimum action: obtain stakeholder consensus on criteria for alternate route selection. Associated considerations include:

- An important minimum criterion is that the geometrics of the alternate route must be able to accommodate all vehicle types. Commercial vehicle restrictions and limited available turning radii that cannot accommodate certain vehicles must be identified. If these restrictions arise, the alternate route plan must make accommodations for vehicles that cannot use the alternate route.

- An alternate route must be reasonably close to the primary route in order to be useful. If the alternate route is too far from the primary route, motorists who are unfamiliar with the area may not be comfortable navigating the alternate route. In rural areas, it may be necessary for the alternate route to be farther away from the primary route, since close parallel roads may not be available.

- The alternate route must have sufficient capacity to accommodate the traffic that is diverted. For example, if traffic is diverted from a 6-lane urban freeway, a 2-lane local street may not have adequate capacity to serve as an alternate route.

Ideal Actions for Establishing Alternate Route Criteria

In addition to obtaining stakeholder consensus on criteria for alternate route selection, consider the following ideal action: set detailed criteria for alternate route selection in addition to the relative priority of each criterion. Associated considerations include:

- Criteria should be chosen to benefit both motorists and the community at large.

- Stakeholders must agree on the relative importance of each criterion. For example, some stakeholders may choose travel time as the most important criterion, while others may prefer a route with a greater travel time that causes less community disruption.

Table 4-2 summarizes various criteria for selecting an alternate route.

Table 4-2. Criteria for alternate route selection

| CRITERION | ENTITY IMPACTED | ACTION |

|---|---|---|

| Proximity of alternate route to closed roadway | Motorist |

|

| Ease of access to/from alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Safety of motorists on alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Height, weight, width, and turning restrictions on alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Number of travel lanes/capacity of alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Congestion induced on alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Traffic conditions on alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Number of signalized intersections, stop signs, and unprotected left turns on alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Travel time on alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Pavement conditions on alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Type and intensity of residential development on alternate route | Community |

|

| Existence of schools and hospitals on alternate route | Community |

|

| Percentage of heavy vehicles (e.g., trucks, buses, RVs) on route from which traffic is to be diverted | Motorist |

|

| Grades on alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Type and intensity of commercial development on alternate route | Community |

|

| Availability of fuel, rest stops, and food facilities along alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Noise pollution | Community |

|

| Transit bus accommodation | Motorist |

|

| Air quality | Community |

|

| Ability to control timing of traffic signals on alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Ownership of road | Motorist/ Agency |

|

| Availability of ITS surveillance equipment on alternate route | Motorist |

|

| Availability of ITS information dissemination equipment on alternate route | Motorist |

|

ASSEMBLE AND INDEX DATA

After alternate route criteria are established, stakeholders may begin assembling and indexing data. If any of the agencies involved have access to a GIS database with pertinent information on roadway characteristics, it would be very useful for this step.

Stakeholders should review all the data available to ensure that the necessary data has been acquired to evaluate potential alternate routes on the basis of the selection criteria. Table 4-3 describes roles that different stakeholders may perform in the process of assembling and indexing data. It should be noted that roles may vary depending on the region and the ownership of roads that are involved in the alternate route.

Table 4-3. Stakeholder involvement in assembling and indexing data

| STAKEHOLDER | ROLE |

|---|---|

| Transportation/public works agency |

|

| Law enforcement |

|

| Fire department |

|

| Emergency medical service |

|

| Transit agency |

|

| Turnpike/toll authority |

|

| Planning organization |

|

| Freeway service patrol |

|

Minimum Actions for Assembling and Indexing Data

The task of assembling and indexing data involves the following minimum action: use a paper or electronic map to determine the location of roads that may be used as alternate routes and to obtain information on these routes. Associated considerations include:

- Stakeholders can use a commercially available paper or electronic map and locate all roadways that are near the route from which traffic is to be diverted. Stakeholders should also check access to and from these roadways to ensure that they connect to each other.

- Information that may be available includes roadway classification, pavement type, geometric information, traffic volumes, development density, and accident data.

Ideal Actions for Assembling and Indexing Data

The following ideal actions may be applied in addition to the minimum action:

|

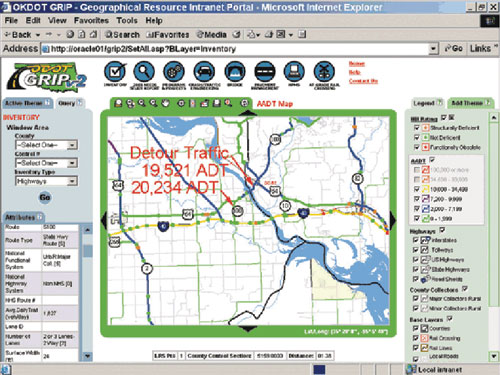

| Figure 4-2. GIS map for alternate route planning in Oklahoma. (Source: Geospatial Solutions) |

- Use a GIS map, if available, to obtain detailed information on available routes. Associated considerations include:

- GIS databases contain a variety of useful information on roads and other features. These features are shown graphically on an electronic map. Here, different features (layers) can be turned on or off as necessary, and symbols may be changed.

- GIS maps, as shown for example in figure 4-2, are ideal for obtaining information on primary routes and candidate alternate routes.

- GIS databases can save time in planning an alternate route by allowing the planners to obtain basic information about the candidate routes, which would otherwise be available only with a field study or through cumbersome research of paper maps and files.

- Information that may be available through a GIS includes roadway classification, pavement type, geometric information, traffic volumes, development density, and accident data.

- If a GIS database shows traffic incident locations, then it can be used to identify a high incident location for which an alternate route should be planned.

- While the lead agency may not have access to GIS, it is possible that other agencies have access to GIS, which can be used in the alternate route planning process. Examples of such agencies include rural or metropolitan planning organizations, municipal or county planning departments, and utilities. If the lead agency does not have access to a GIS database, then they should ask other stakeholders if such databases exist and if they may use them to develop the alternate route plan.

- Because no single database can include all information about every aspect of a roadway network, it is necessary to consult other sources, such as a traffic study, to obtain certain data.

- GIS databases contain a variety of useful information on roads and other features. These features are shown graphically on an electronic map. Here, different features (layers) can be turned on or off as necessary, and symbols may be changed.

- Consult planning organizations for access to travel demand models that can be used for obtaining data. Associated considerations include:

- All travel demand models have a highway network; some larger planning organizations may also have demand models that include transit networks. The networks typically contain information for each link, such as number of lanes, capacity, length, speed limit, functional category (freeway, arterial), and area type (metropolitan, urban/rural). When available, many links will include traffic volume information. Transit links will include information such as route number, headway times, capacity, and fare structure.

- Sometimes travel demand model networks may be even more readily available than GIS databases and may provide extensive roadway information. The demand model systems used by planning organizations have the capability of displaying the roadway networks in a layout similar to GIS. Some software transportation planning packages combine the capabilities of a GIS with travel demand models. These tools provide a quick and powerful way for the user to identify and display capacity, lanes, and speeds as part of the alternate route planning process for assembling and indexing data.

- All travel demand models have a highway network; some larger planning organizations may also have demand models that include transit networks. The networks typically contain information for each link, such as number of lanes, capacity, length, speed limit, functional category (freeway, arterial), and area type (metropolitan, urban/rural). When available, many links will include traffic volume information. Transit links will include information such as route number, headway times, capacity, and fare structure.

- Consult transportation agencies for information on typical traffic volumes, roadway geometry, signage, and traffic control devices. Transportation agencies may have detailed information on the roadways being investigated as potential alternate routes. This data will assist in applying the selection criteria to candidate alternate routes during the selection process.

- Consult law enforcement personnel and/or transit operators for information on traffic operations. Law enforcement personnel and transit operators may have firsthand knowledge of typical traffic conditions from policing and traveling the alternate route on a daily basis. Law enforcement may have records of travel speeds and incident data. Transit agencies may log travel times during different times of the day along portions of candidate alternate routes from scheduled monitoring activities. This data should complement data provided by the transportation/public works agency.

- Consult freeway service patrols operators for information on traffic operations and incident frequency. Freeway service patrols, namely its administering agency, may have records of incident occurrence, type, and duration. Also, since freeway service patrols travel a particular route on a daily basis, operators may have firsthand knowledge of typical traffic conditions at different times of the day and days of the week.

(Chapter 4 is continued on next page.)