Alternate Route Handbook

2. Background

|

| Figure 2-1. Example of an incident requiring the use of an alternate route. (Source: New Jersey DOT) |

Literature Review

A review of the literature and an Internet search yielded limited information relating to alternate route planning. The literature revealed that most alternate route information had been developed in the context of incident, emergency, and work zone management. However, there is very little information that provides guidance on alternate route selection and plan development. Details of the documents reviewed are discussed in this chapter of the handbook.

Alternate Route Selection

One notable document relating to alternate route selection was from Geospatial Solutions.1 This document discussed the use of GIS in planning alternate routes when a bridge on I-40 in Oklahoma collapsed. This source presented GIS and traffic simulation as useful techniques in the alternate route selection and evaluation process.

Traffic Management Planning

Most available information regarding specific alternate route plans focuses on the traffic management planning aspect of alternate route plans. A search of the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) journals yielded information regarding alternate route planning. Notable examples included information on alternate routes during the reconstruction of Interstate 95 (I-95) in Florida; the DIVERT system in St. Paul, Minnesota; and the CHART system in Maryland. These examples are discussed in the following:

I-95 Reconstruction: A System Maintenance of Traffic Approach2 discussed the use of traffic simulation in developing a freeway-to-street alternate route plan, as well as traffic control measures to accommodate traffic along the street alternate route. Traffic control measures included computer-controlled traffic signals, regional signage, encouragement to use public transit, a public information/rideshare service, a freeway incident management program, and visual barriers to reduce rubbernecking. The document highlights the advance planning that is needed to ensure efficient traffic flow and user satisfaction during a major reconstruction project.

DIVERT: DIVERT3 is an acronym for During Incidents, Vehicles Exit to Reduce Travel Time. This system centers on a single, highly congested interchange in downtown St. Paul, Minnesota, and involves implementing alternate routes to divert traffic away from the interchange and through the city during a freeway incident. The methods used to divert traffic to the alternate route include changeable message signs (CMSs), blankout signs, and trailblazer signs. The freeway is monitored using closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras and loop detectors to detect incidents. Loop detectors are also used on the alternate routes to adjust traffic signal timing to accommodate diverted traffic. The traffic management methods used in DIVERT are significant Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) applications that are used in many modern alternate route plans.

CHART: CHART4 is an acronym for Coordinated Highways Action Response Team. CHART started with the "Reach the Beach" program, which involved using ITS to help motorists find the best route from the Baltimore-Washington metropolitan area to ocean beaches. A key component of the program's success involved achieving coordination and collaboration between various program stakeholders. Techniques used to determine the best routes and manage traffic in real-time include:

- Incentives to travel during off-peak periods.

- Traffic surveillance, including loop detectors, aerial surveillance, and motorcycle patrols.

- Information dissemination, including highway advisory radio (HAR), commercial radio feeds from a transportation management center (TMC), CMSs, telephone hotline, and sound trucks patrolling the rear-of-traffic queues.

- Incident management initiatives.

Alternate Route Implementation During Catastrophic Events

The FHWA document Effects of Catastrophic Events on Transportation System Management and Operations contains a cross-cutting study, as well as a series of documents for specific incidents, including the events of 9/11, the Howard Street rail tunnel fire in Baltimore, MD, and the Northridge earthquake in California. The cross-cutting study5 and the documents about the rail tunnel fire6 and the earthquake7 are available online. In both the rail fire and the earthquake, alternate routes represented a key response strategy needed to manage traffic in the affected areas.

Review of Guidance and Best Practices

FHWA Traffic Incident Management Handbook: The FHWA Traffic Incident Management Handbook8 suggests the use of alternate routes for handling traffic demand during an incident. The handbook stresses the need for coordination between stakeholders. Information is provided on alternate route selection criteria and evaluation and traffic management planning along the alternate route. The traffic management planning techniques suggested include the use of CMSs and HAR to notify motorists of the alternate route, and modifying the timing of traffic signals and ramp meters to accommodate the alternate route traffic. The Traffic Incident Management Handbook refers readers to National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Synthesis 2799 for guidance on alternate route planning.

NCHRP Synthesis 279: NCHRP Synthesis 279, Roadway Incident Diversion Practices,9 provides information on state-of-the-practice alternate route planning and implementation, based on a selected survey of transportation agencies that have developed and implemented alternate route plans. The synthesis provides profiles of individual successful roadway incident diversion practices and addresses the following topics:

- Type of diversion scenarios used in metropolitan and rural areas.

- Planning process used to develop an alternate route plan.

- Criteria used to select an alternate route during the planning process.

- Methods used to detect and verify incidents.

- Criteria considered in the decision to implement an alternate route plan.

- Resources used to inform motorists to

divert.

- Resources used to guide motorists along the alternate route and back to the original roadway.

- Methods used to accommodate diverted traffic along the alternate route.

- Perceived and measured benefits of alternate route plans and any reported barriers to plan development and implementation.

Historical Perspective: District 7 of the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) pioneered the development and implementation of alternate route plans for responding to the occurrence of major incidents.9 In 1971, the District initiated the process of developing 2,500 alternate route maps, covering 764 km (475 mi) of freeway. Each map identified several components vital to the alternate route implementation process, including identification of problem location, primary and secondary alternate routes, implementation guidelines, manpower requirements and locations, required signing, necessary closures, responsible parties and associated phone numbers, and special notes unique to the incident area. Caltrans found it essential to coordinate all agencies involved in the development process and cited a good working relationship throughout the planning stage, with local agency traffic personnel having jurisdiction over the proposed alternate routes.9

ALTERNATE ROUTE APPLICATIONS

The use of alternate routes represents a key traffic management strategy for an impact to normal highway operations that results from any type of planned or unplanned event, from traffic incidents and emergencies to planned special events. The same alternate route selection and plan development process applies regardless of the circumstances surrounding the intended implementation of the planned alternate route. This section presents an overview of alternate route plan applications in the context of different types of planned and unplanned events.

Major Traffic Incidents

|

| Figure 2-2. Buckling of I-95 due to tanker fire. (Source: Hartford Courant11) |

In March 2004, an accident involving a tanker truck destroyed a section of I-95 in Bridgeport, CT.10 This section of roadway, located on the northern edge of the New York metropolitan area, is one of the busiest in the Nation and part of the primary East Coast Interstate highway. Due to the severity of the damage and the high traffic volumes in the area, implementation of alternate routes was especially important in this situation. Figure 2-2 shows a picture of I-95 in Bridgeport, CT, after it buckled following the tanker crash.

In order to separate the various types of traffic that use I-95, three levels of alternate routes were planned:

- A regional alternate route was designed for through traffic destined to the next major metropolitan area. The regional alternate route consisted of a freeway facility that provided considerable savings in travel time, versus local alternate routes, to traffic traveling through the region. Moreover, the regional alternate route reduced unnecessary traffic demand on local alternate routes, thus optimizing network operations.

- An in-State alternate route was designed for regional traffic that required access to I-95 downstream of Bridgeport. Because the main in-State alternate route, the Merritt Parkway, is not open to trucks, separate in-State alternate routes were needed to service truck traffic.

- A local alternate route was designed for local traffic destined to the immediate Bridgeport area, using a network of local city streets as the alternate route. A local freeway alternate route was designed for trucks.

In addition to the alternate routes, other measures were taken to reduce traffic demand in the corridor, as follows:

- Encouraging travelers to use mass transit instead of driving.

- Increasing mass transit schedules.

- Encouraging travelers to carpool, and advertising services to set up carpools.

- Restricting vehicles with oversize/overweight permits to certain roadways, and closing certain State border crossings to these vehicles.

Emergencies

Alternate route plans prove valuable when a natural disaster renders a transportation facility unusable for an extended period. The Northridge earthquake in January 1994 destroyed many freeway sections in the greater Los Angeles, CA, area.7 Because the Los Angeles area is already one of the most congested in the Nation, and is heavily dependent on automobile transportation, this disaster was very costly to the region. The following freeways incurred major damage:

- I-5: The Golden State Freeway

- SR 14: The Antelope Valley Freeway

- I-10: The Santa Monica Freeway

- SR 118: The Simi Valley Freeway

Transportation planning required multi-jurisdiction and multidisciplinary coordination that involved numerous agencies, including Caltrans, the Los Angeles Department of Transportation, and the California Highway Patrol. Alternate routes, consisting of city streets, were developed for all closed sections of freeways. As traffic conditions changed due to increased traffic volume and changed travel patterns, alternate routes were modified. Traffic signal timing plans along alternate routes were modified to accommodate diverted traffic.

Figures 2-3 and 2-4 show damaged freeways following the earthquake. Figure 2-5 shows a map of some alternate routes used in response to the catastrophe.

| ||

| ||

|

Homeland Security

Alternate route plans mark an integral component of traffic management plans contained within transportation agency emergency response plans. In fact, agencies may implement an alternate route plan as a means to protect critical infrastructure and key assets from potential acts of violence. As such, alternate route plans represent a key homeland security initiative to be prepared for any future incidents. The FHWA/American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Blue Ribbon Panel on Bridge and Tunnel Security recommended "procedures for restoring service and establishing alternate routes" as a component to a recommended countermeasure, planning and coordination, for bridge and tunnel owners and operators for their use in planning and implementing more effective security practices.12 This national panel of bridge and highway engineers convened for the purpose of developing short- and long-term strategies for improving the safety and security of the Nation's bridges and tunnels and providing guidance to highway infrastructure owners/operators.

| ||

|

Alternate route plans have the ability to reduce the severity of impact on transportation system operations that may result from a disaster affecting the highway infrastructure. Major bridges and tunnels are common bottleneck points in a regional transportation system and also potential targets for acts of violence. An incident that renders a major bridge or tunnel unusable can have a disastrous effect on traffic flow within the affected corridor and across the region. Alternate route plans are an important tool to help an area cope with the loss of a major bridge or tunnel. For example, as shown in figure 2-6, Federal authorities prohibit commercial trucks and buses from traversing U.S. 93, a North American Free Trade Agreement truck route, across the Hoover Dam. In response to this order, transportation agencies installed special trailblazer signs (see figure 2-7) and maintain an intensive information campaign using roadside traveler information devices and other information dissemination methods.

During an emergency, the use of alternate routes and evacuation routes may often overlap. Mass evacuation may require the use of alternate routes when the primary evacuation route becomes too congested. Alternate routes are also needed in order to divert traffic away from the area that is being evacuated due to the incident.

A Guide to Updating Highway Emergency Response Plans to Terrorist Incidents13 includes recommendations for State transportation agencies to update emergency response plans in the post-9/11 world. The guide lists alternate route plans as a useful technique in any emergency response plan.

The ITS and traveler information resources typically used for the ideal implementation of an alternate route plan could be used to both implement the plan and monitor the highway infrastructure for signs of any secondary attack. Any secondary attacks that render roadways impassable can be addressed through alternate route strategies. Under these conditions, promoting the smooth flow of traffic to clear the highway as soon as possible is of the utmost importance in resuming any semblance of normality. Panic and uncontrolled flight are always a possibility; therefore, these plans must be prepared in advance and rapidly implemented when conditions warrant. Many devices used to support alternate route implementation and monitoring are also useful for homeland security. Surveillance cameras are frequently used to monitor traffic conditions along an alternate route, and are also used to detect incidents that may necessitate the use of an alternate route. Cameras are also useful to detect suspicious activity. If an act of violence does occur, traveler information dissemination devices are useful to notify motorists of the situation and to divert traffic away from the incident and away from transportation facilities that are closed. These devices may mitigate the severity of a human-caused incident.

Planned Special Events

An alternate route plan represents a contingency plan for operating high-capacity

freeway/arterial facilities serving a planned special event venue. It serves to reduce demand in response to congestion caused by event-generated traffic demand or a capacity-restricting traffic incident. In other instances, an alternate route plan becomes a critical component of the overall event traffic management plan when roadway or bridge construction activities limit the capacity of mainline corridor flow routes. Transportation system operators should also promote travel choice alternatives, such as using other travel modes, as an option to driving alternate routes.

Stakeholders may also develop alternate route plans for the purpose of accommodating background traffic not destined for the event venue during planned special events. For instance, to accommodate regional through traffic, TMC operators can implement freeway-to-freeway diversion through control of permanent CMSs and HAR. Arterial-to-arterial diversion is needed to accommodate background traffic during planned special events occurring in city downtown or commercial areas, where arterials and local streets adjacent to the event venue serve a significant volume of background traffic. In turn, the addition of event-generated traffic causes congestion and impacts commercial businesses (e.g., restaurants, hotels, retail stores). This strategy involves (1) restricting commercial street access to businesses employees, customers, emergency vehicles, taxis, and transit buses, and (2) implementing an alternate route to direct background through traffic and event-generated traffic around the restricted street.14

STATE-OF-THE-PRACTICE SURVEY

As part of this study, agencies throughout the United States and Canada were surveyed about various aspects of their alternate route plans, in addition to the process involved in developing such plans. A brief questionnaire was prepared for distribution to national stakeholder groups in order to obtain the most current state-of-the-practice information on roadway incident diversion practices in addition to case study examples. This questionnaire was aimed at State departments of transportation (DOTs) and other transportation agencies involved in alternate route planning and implementation. It consisted of three sections that collectively addressed alternate route planning processes, alternate route selection and plan development, and traffic management planning and associated strategies.

A total of 26 survey responses were received from agencies throughout the United States and Canada. The surveyed agencies represent 17 States and one Canadian province. Six of the States and the province submitted responses from multiple districts. Of these respondents, 19 were from State DOTs, 2 were from metropolitan planning organizations, 2 were from county transportation departments, and 3 were from Canadian transportation agencies. The survey respondents addressed the development and implementation of alternate route plans on a Statewide, district, or local level encompassing one or multiple facilities.

The following questions were specifically related to the three phases of alternate route planning:

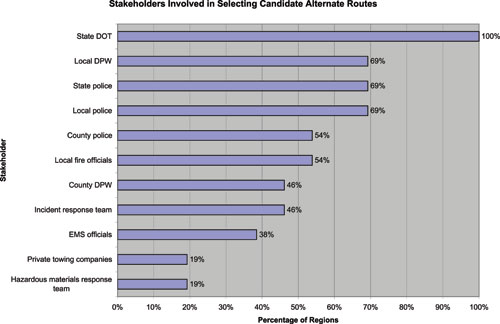

- Which of the following stakeholders were involved in selecting candidate alternate routes? The results are shown in figure 2-8.

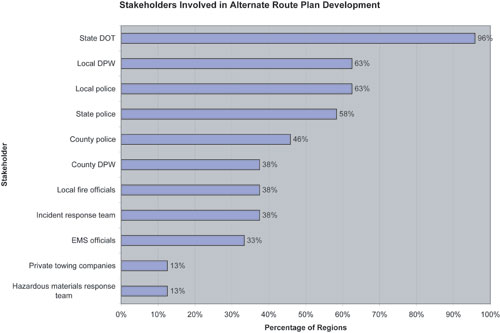

- Which of the following stakeholders were involved in developing alternate route plans? The results are shown in figure 2-9.

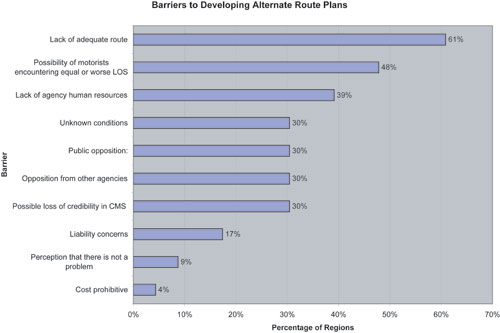

- Which of the following barriers did stakeholders in your jurisdiction encounter when considering the need to develop an alternate route plan? The results are shown in figure 2-10.

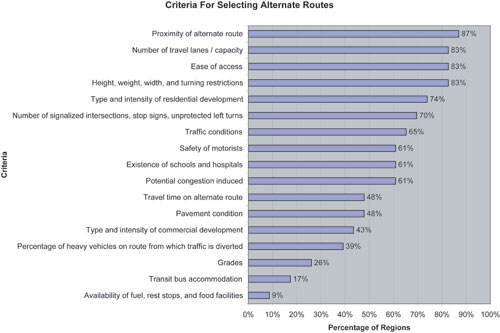

- Which of the following criteria were considered in selecting alternate routes? The results are shown in figure 2-11.

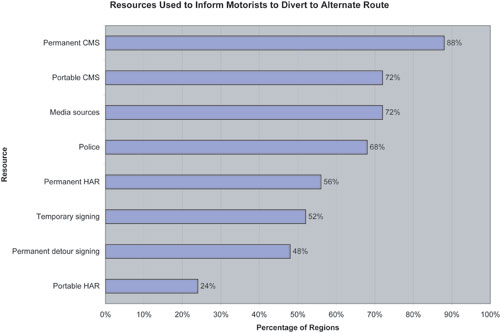

- Indicate the resources used to inform motorists to divert to an alternate route. The results are shown in figure 2-12.

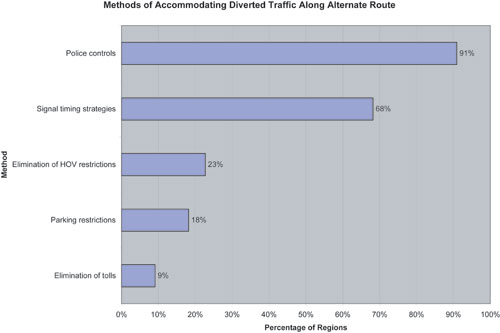

- Indicate the methods used to accommodate diverted traffic along an alternate route. The results are shown in figure 2-13.

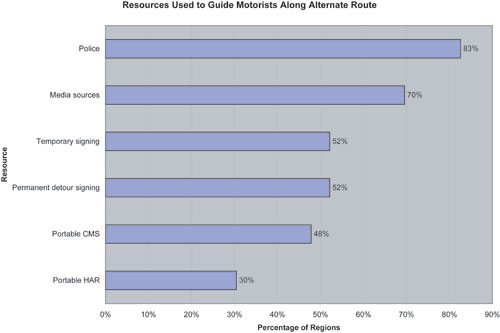

- Indicate the resources used to guide motorists along an alternate route and back to the mainline. The results are shown in figure 2-14.

|

| Figure 2-8. Stakeholders involved in selecting candidate alternate routes. |

|

| Figure 2-9. Stakeholders involved in alternate route plan development. |

Note: One agency reported as a barrier that municipalities require financial compensation for the use of municipal streets as an alternate route. |

| Figure 2-10. Barriers to developing alternate route plans. |

Note: One agency stated that the ownership of the roadway (State vs. local) could be used as a selection criterion. |

| Figure 2-11. Criteria for selecting candidate alternate routes. |

|

| Figure 2-12. Resources used to inform motorists to divert to an alternate route. |

|

| Figure 2-13. Methods of accommodating diverted traffic along an alternate route. |

|

| Figure 2-14. Methods of guiding drivers along an alternate route. |

In addition to the general survey questions, there was also a question on what criteria agencies use for implementing or terminating an alternate route plan. Generally, the criteria for implementing an alternate route require that all or a substantial portion of the primary route capacity be reduced (e.g., two or more travel lanes blocked) before an alternate route is deployed. Some agencies do not have any specific criteria, and the decision to implement the alternate route plan is left up to ranking incident responders at the time of the incident. Table 2-1 indicates examples of decision criteria that various agencies use to determine the need for alternate route implementation.

Table 2-1. Criteria for implementing alternate route plans

| AGENCY | CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| North Carolina DOT - main office |

|

| North Carolina DOT - Charlotte regional office |

|

| New Jersey DOT |

|

| Ministry of Transportation, Ontario, Canada |

|

| Regional Municipality of Halton (Ontario, Canada) |

|

| Oregon DOT |

|

| New York State DOT, Region 1 |

|

| Florida DOT District IV |

|

| ARTIMIS (Ohio/Kentucky) |

|

| Ada County, Idaho |

|

| Wisconsin DOT (Blue Route) |

|

The survey revealed that several agencies have specific criteria for determining when an alternate route is no longer required. For most agencies, however, the decision to terminate the alternate route plan is based on a judgment call made by ranking incident responders involved in alternate route implementation. Table 2-2 indicates criteria that some agencies use in determining when to terminate use of an alternate route.

Table 2-2. Criteria for terminating alternate route plans

| AGENCY | CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| Ministry of Transportation, Ontario, Canada |

|

| Regional Municipality of Halton (Ontario, Canada) |

|

| North Carolina DOT - Charlotte regional office |

|

| New Jersey DOT |

|

References

- Adams, J., ODOT Gets a GRIP on Transportation, Geospatial Solutions [Online]. [September 26, 2003].

- Edelstein, R., and J.A. Wolfe, I-95 Reconstruction: A System Maintenance of Traffic Approach, ITE Journal, Vol. 59, No. 6, June 1989, pp. 39-43.

- Wright, J.L., ITS Projects in St. Paul: DIVERT and Advanced Parking Information System, ITE Journal, Vol. 66, No. 9, September 1996, pp. 33-35.

- Kassof, H., Maryland's CHART Program: A New Model for Advanced Traffic Management Systems, ITE Journal, Vol. 62, No. 3, March 1992, pp. 33-36.

- Effects of Catastrophic Events on Transportation System Management and Operations: A Cross Cutting Study, U.S. Department of Transportation, January 2003.

- Effects of Catastrophic Events on Transportation System Management and Operations: Howard Street Tunnel Fire, Baltimore City, Maryland, July 18, 2001, U.S. Department of Transportation, January 2003.

- Effects of Catastrophic Events on Transportation System Management and Operations: Northridge Earthquake, January 17, 1994, U.S. Department of Transportation, January 2003.

- PB Farradyne, Traffic Incident Management Handbook, Federal Highway Administration, Washington, DC, November 2000.

- Dunn, W.M., R.A. Reiss, and S.P. Latoski, Synthesis of Highway Practice 279: Roadway Incident Diversion Practices, Transportation Research Board, National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Washington, DC, 1999.

- Connecticut Department of Transportation Web site.

- Hartford Courant, Photo Gallery, Hartford, CT, March 25, 2004 [Online].

- The Blue Ribbon Panel on Bridge and Tunnel Security, Recommendations for Bridge and Tunnel Security, Prepared for AASHTO Transportation Security Task Force and Federal Highway Administration, September 2003.

- Parsons Brinckerhoff – PB Farradyne, A Guide to Updating Highway Emergency Response Plans for Terrorist Incidents, AASHTO Security Task Force, May 2002.

- Latoski, S.P., W.M. Dunn, B. Wagenblast, J. Randall, and M.D. Walker, Managing Travel for Planned Special Events, Federal Highway Administration, Washington, DC, September 2003.