Freeway Management and Operations Handbook

Chapter 9 – High Occupancy

Vehicle Treatments

Page 2 of 2

9.3 Implementation & Operational Considerations

The numerous issues associated with policy development, planning, designing, implementing, marketing, operating, enforcing, and evaluating HOV facilities are addressed (in a comprehensive manner) in the NCHRP "HOV Systems Manual" (Reference 1) and other references noted herein. This section only provides a brief overview of some of these issues, many of which are identified in Reference 1 as "the key elements to achieving the desired project goals and objectives."

9.3.1 Planning

In order for HOV systems and facilities to be properly integrated within the freeway system, system-planning needs to occur at various levels, including strategic planning, long-range system planning, short-range planning, and service or operations planning. At the strategic planning level, freeway and transit agencies need to determine their roles, missions, and types of HOV services they want to provide in a metropolitan area. Through the long-range planning process, agencies can ensure that HOV facilities and services are incorporated into the future design of freeway systems and that funding for capital-intensive facilities are programmed into area transportation improvement plans.

9.3.2 Interagency Coordination / Stakeholders

HOV facilities require that staff from agencies responsible for the freeway and roadway system, transit services, rideshare programs, and other programs work together. Interagency cooperation and coordination is critical to the success of an HOV project. That said, experience indicates that one agency or group needs to have overall responsibility. Experience has also indicated that one individual or a small group of individuals (i.e., "champions") has been instrumental in the development, promotion, and support if most HOV projects (1).

Table 9-2 is from the HOV Systems Manual, and presents the roles of each of these partners in developing, operating and enforcing an HOV facility on a Freeway. In addition to these stakeholders, the HOV process needs to also consider the following:

- Policy Makers: Elected and appointed officials should be kept informed on the use of HOV facilities. Since elected officials, especially members of the state legislature are often the driving force behind HOV operational changes, it is important to keep these individuals informed on bus, carpool, and vanpool use of HOV facilities. Briefings, newsletters, E-mails, and other techniques may be used to provide ongoing updates on vehicle volumes and passenger levels, as well as any potential issues associated with HOV lanes.

- Media: The broadcast and print media represent an important constituency group for HOV facilities. The media has a significant influence on public perceptions and opinions, and represents an important method of getting information out to commuters, the public, and policy makers. Providing representatives from the media with accurate and timely information on HOV strategies – particularly operational changes – will help ensure that commuters and the public are aware of the changes, understand the reasons why changes are made, and comply with new requirements.

- Commuters and General Public: Commuters, especially HOV users, and the general public represent the constituents of HOV projects. Obtaining input from these groups through surveys, focus groups, and other market research techniques may be appropriate in assessing different HOV operational strategies. Communicating new requirements to these groups is also critical.

| Agency or Group | Potential Roles and Responsibility |

|---|---|

| State Department of Transportation |

|

| Transit Agency |

|

| State Police |

|

| Local Police |

|

| Local Municipalities |

|

| Rideshare Agency |

|

| Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) |

|

| Federal Agencies – FHWA and FTA |

|

| Other Groups |

|

9.3.3 Operations Planning / HOV Policies

The development of an operations plan is foremost in the success of the HOV facility. It should be noted that the development of an operations plan cannot be done in isolation, but needs close integration with the facility's enforcement plan (1). The plan should also address the various policy issues associated with HOVs, including those discussed below:

9.3.3.1 Operational Alternatives for the HOV

This addresses the type of HOV facility, and it has a direct and significant impact on other elements of the plan such as the ingress and egress and enforcement. The operation of separated HOV roadways may be reversible or two-way. The facility can be restricted to HOVs during peak periods only or throughout the day. Limiting access to a reversible HOV facility is crucial if the facility is to be operated in a safe and efficient manner. A system of gates must be considered at each end (and at any intermediate access points) to prevent wrong-way traffic from entering the facility, if located on a freeway. In addition to these features, this type of facility should also have a system of changeable message signs (CMS) that inform commuters as to the operational status of the facility (open or closed).

9.3.3.2 Vehicle Eligibility Requirements

The HOV facility provides operators and managers the flexibility to match the vehicle eligibility (and the vehicle occupancy requirements) to the lanes. Further, each can be changed to maintain the proper balance if necessary. Vehicle eligibility (i.e., what types of vehicles can use the facility) is one of the first issues that must be determined to develop the Operations Plan. Various types of vehicles can be considered for the use on the HOV facility including:

- Buses

- Vanpools

- Carpools

- Taxis

- Emergency vehicles

- Low-emission vehicles

- Commercial vehicles

- Airport Shuttles and other services

- Motorcycles

- Tolled vehicles (HOT)

9.3.3.3 Vehicle Occupancy

Vehicle occupancy (e.g., 2+ or 3+) should be examined against the demand for the facility to estimate the impact the occupancy requirements may have on traffic flow. The goal is to implement HOV facilities in such a way that balances the flexibility of HOV growth and the public perception as to the use of a facility. An initial minimum vehicle occupancy requirement must be selected to optimize the efficiency of the facility. The selection must allow for growth in traffic volumes as more commuters choose to switch to carpooling arrangements and take advantage of the travel time and fuel savings. Title 23 United States Code 102(A) allows State departments of transportation to establish the minimum occupancy requirements for vehicles operating on HOV lanes; except that no fewer than two occupants per vehicle may be required and that motorcycles and bicycles shall not be considered single occupant vehicles. Retaining the potential to carry more people over time offers important operational flexibility. At the same time, though, public perception of the adequacy of HOV lane usage must also be addressed. Peak hour HOV traffic volumes need to be high enough to help mitigate public concerns over underutilization of HOV facilities. The positive aspect of 2+ eligibility is that a staged resource of commitment to ridesharing is being established. Less work is involved in forming a 2+ carpool versus a 3+ carpool, and the base volume to draw from is considerably greater. There may be less eventual resistance to adding a third passenger than to forming an initial 3+ carpool.

Subsequent changes in occupancy requirements need to be weighed with projected future demand. Implementing an operational change from 2+ to 3+ occupancy could reduce vehicular demand by as much as 75 to 85 percent. This could be severe if only a 10 to 20 percent reduction in demand is necessary for the near future. A new HOV 3+ lane typically may carry only a few hundred peak-hour vehicles, while an adjacent freeway lane is carrying 1500 to 2000 peak-hour vehicles. Even though the HOV lane may be carrying more peak-hour person trips than an adjacent general purpose lane, the traveling public may perceive the lane to be underutilized. Additionally, there is the potential political difficulty in making a change from 2+ to 3+, as evidenced by the fact that very few such attempts have been successful. Varying occupancy requirements by time-of-day is another possibility.

Another consideration is regional consistency. It is the exception to have different occupancy (or eligibility) requirements on different facilities or in different corridors within the same metropolitan region.

9.3.3.4 Hours of Operation

Hours of operations for an HOV facility may be characterized as:

- 24-hour continuous use

- Extended morning and afternoon hours – in this scenario, the lanes are used for much of the morning and afternoon.

- Peak Period only

- Dynamic – only when warranted (metered ramps with bypass)

A number of factors, including geometric design, volumes of HOV and mixed-flow traffic, hours of congestion, and regional consistency will influence HOV operating hours. Twenty-four hour HOV use of priority facilities is sometimes preferred, because violations tend to be lower and there is less motorist confusion. Also, 24-hour use may provide a greater overall incentive for the formation of new carpools. Some HOV facilities, such as reversible lanes, may not be conducive to 24-hour operation. The hours of operation for reversible facilities must allow time for a variety of necessary functions, such as clearing the lane, moving gates, and changing signing.

Part-time operation provides benefits only during the peak hours of defined need, allowing all traffic to use the lanes during other periods. This approach can reduce enforcement requirements and minimize public criticism during periods when the HOV lane appears empty. Part-time use of a shoulder as an HOV facility should be implemented only after careful consideration of operational and safety problems. The right shoulder HOV facility differs from a part-time HOV lane that reverts to mixed-flow use during off-peak periods, in that the shoulder serves as a refuge for emergency breakdowns. Its use needs to be limited to a small number of vehicles because of the inherent conflicts at right side entrance and exit ramps. The shoulder facility requires special delineation and signing, and involves separate enforcement problems for both peak and off-peak periods. Motorists may tend to use the shoulder as a freeway lane during off-peak hours when it should be used as a shoulder.

9.3.4 Public Awareness and Marketing

Marketing and promoting the HOV facility is paramount to its successful implementation. More than one facility has either failed or had significant setbacks as a result of not informing or involving the public. The process of successful marketing of HOV facility includes (1):

- Public Involvement: An HOV facility must have public support to be successful. Ensuring that the public is involved early and throughout the planning, design, and implementation stages can help ensure this support. A variety of methods can be used to encourage the participation of commuters, travelers, neighborhood groups, and other organizations. These include meetings, workshops, surveys, focus groups, charettes, and hearings.

- Education: Building on the early involvement of the public, ongoing public education (and marketing activities) can also enhance the chance of a successful HOV project. Experience indicates that ongoing outreach efforts with the public and policy makers are needed even with effective HOV facilities. Given the turnover in elected and appointed officials, the numerous demands on these individuals, and the multitude of projects and programs vying for the attention of officials and the public, regular updates on the use, effectiveness, and benefits of HOV facilities are needed. The ongoing reinforcement of travel options is also important for new residents as well as long-term commuters.

- Marketing: Building from the two other elements, promoting the facility's or project's information to a wider audience provides a means to target specific audiences with specific information. The "HOV Marketing Manual" (Reference 7) provides detailed information on HOV marketing, as summarized in Table 9-3.

|

9.3.5 Enforcement

Enforcement of vehicle-occupancy requirements and other policies are critical to the successful operation of HOV facilities. HOV enforcement programs help ensure that operating requirements, including vehicle-occupancy levels, are maintained to protect HOV travel time savings, to discourage unauthorized vehicles, and to maintain a safe operating environment. Visible and effective enforcement promotes fairness and maintains the integrity of the HOV facility to help gain acceptance of the project among users and non-users (8).

Public acceptance of an HOV project is closely linked to the perception that the facility is well used and that the vehicle occupancy requirements are enforced. Support for an HOV facility will be lessened if commuters traveling in the adjacent freeway lanes feel the privilege of using the HOV lanes is being abused. Ensuring that the project design includes adequate and safe enforcement areas, and that visible ongoing enforcement is provided are important to the success of an HOV project (1).

Detection and apprehension of violators, and effective prosecution of violators, are essential. Therefore, law enforcement personnel with full capability to issue citations must be employed on HOV facilities. Moreover, police officers help ensure the safe and efficient operation of the facility. Depending on the type of facility and priority users, the potential safety and operational problems caused by vehicle breakdowns, wrong way movements and/or other vehicles' encroachments into the HOV facility may have an adverse impact on operations and must be a concern of the enforcement authority.

Effective enforcement usually includes a number of components. The following general elements should be considered in developing and conducting an enforcement program (8):

- Legal authority to enforce a facility,

- Nature of citations for violations and the level of fines,

- General enforcement strategies,

- Specific enforcement techniques,

- Funding,

- Communicating the program elements to users, non-users, and the public.

Enforcement strategies for HOV facilities can generally be categorized into four basic approaches – routine enforcement, special enforcement, selective enforcement and self-enforcement. All of these strategies may be appropriate for consideration with the various types of HOV projects.

A variety of enforcement techniques can also be used to monitor HOV facilities. These techniques focus on providing surveillance of the lanes, detecting and apprehending violators, and issuing citations or warnings to violators. Examples of approaches include stationary patrols, roving patrols, team patrols, multipurpose patrols, electronic monitoring, citations or warning by mail. Most areas use a combination of enforcement techniques.

A 1988 Texas Transportation Institute study (reference 9) of the enforcement procedures for HOV lanes determined the following key concepts related to effective HOV enforcement:

- The level of enforcement needed is dependent upon facility type. In general, concurrent flow facilities require more enforcement than do separated roadway and contraflow facilities.

- To be effective, an officer must have a safe and convenient place to issue citations or warnings. The enforcement activity should be in view of HOV users so that they can see when the lane restrictions are being enforced; however, it should not interfere with traffic on the HOV and mixed-flow lanes.

- To preclude high violation rates, a highly visible enforcement presence has to be maintained at a level where potential violators and legitimate users believe that violators have little chance to use the lane without getting caught.

- On limited access facilities, diverting potential violators before they can traverse some part of an HOV lane can be safer and more efficient than apprehending them after the fact. Whenever possible, enforcement areas should incorporate this concept.

Where enforcement is difficult to accomplish, or perceived as being unsafe, police may avoid apprehending violators, resulting in increasing numbers of illegal vehicles using the lane. Where enforcement has been a problem, 60 percent or more of the vehicles that used the lanes were violators. Experience suggests that steady doses of routine enforcement, combined with moderate application of special enforcement, can generally keep violation rates on exclusive HOV facilities in the 5 to 10 percent range. Heavy, consistent doses of special enforcement would be necessary to have violation rates below 5 percent. There are locations where no amount of enforcement can bring violation rates to an acceptable level (10).

In some metropolitan areas, programs have been initiated where motorists can call in to report HOV facility violators. Appropriate literature is sent to frequent violators, and enforcement personnel can make a point of watching for these vehicles in the HOV lane. These "so called" HERO programs can be helpful in reducing violation rates. Also, a system of video cameras combined with officer observation may be considered for non-occupancy infractions such as speeding or toll evasion (where pricing is applied), where state laws permit such technology. Currently, no state allows video for occupancy infractions because the system cannot be supported as fool-proof in the courts. Another factor that will have a positive impact on the violation rate is the cost of the fine for a violation. Fines exceeding $250 for first offenders have been used, significantly lowering the violation rate.

9.3.6 Performance Monitoring

As discussed in Chapter 4, evaluating the effectiveness of HOV treatments (or any freeway management strategy for that matter) should not be considered a one-time activity, but should be part of a periodic review of the effectiveness of the component and of the overall system. In addition to providing information to the sponsoring agencies on the effectiveness of the treatment(s), the information would be helpful in communicating the effectiveness of the project to the public and enhancing a general understanding of the role that the HOV project has performed.

For each objective associated with the HOV program, the appropriate measure(s) of effectiveness should be identified, along with the desired threshold level of change that will be used to determine if the facility has met the objective. Commonly used objectives (i.e., for new HOV projects that add a lane to the freeway) and measures of effectiveness are identified in Table 9-4.

| Objective | Measures of Effectiveness |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9.3.7 Other Considerations

Other issues that may be of concern with the development and implementation of an HOV treatment include the following:

- Logical HOV Segments: Ensuring that logical segments of an HOV project are opened for operations enhances the chance of a successful facility. For example, projects that allow HOVs to bypass congested freeway segments and provide good access may be better receives than projects located where there is no congestion or those which funnel HOVs back into sections of heavy traffic (1).

- Supporting Facilities and Service: Successful HOV projects encompass more than just the HOV facility. Elements such as park-and-ride lots, new or expanded bus services, ramp meter bypass lanes, and other supporting components all contribute to the success of an HOV project (1).

- Supporting Programs and Policies: The existence of other supporting programs and policies also enhances the likelihood of a successful project. Ridesharing programs, guaranteed ride home programs, parking management and pricing policies, employer effort, land use policies and zoning ordinances may encourage HOV use (1).

- Scheduling: If the HOV project is a retrofit, implementation scheduling can be complicated by a variety of unknowns, generally related to the policies and procedures of the various agencies involved. If the project requires daily monitoring (e.g., contraflow or reversible-flow operations), an additional period following construction completion should be included for pre-operation testing. This period allows police to refine enforcement strategies and the operations team to make minor adjustments in the facility design prior to operation. The advance period will vary by project and type of facility to acquaint bus operators, deployment staff, police, and others with how to handle daily operation, maintenance, and emergencies (11).

- HOV Operation During Construction: One of the most effective methods of cultivating an early market for an HOV project is to start offering preferential treatment during the construction phase. Additionally, this approach can be a cornerstone of the traffic management plan aimed at preserving corridor flow during construction activities. These benefits often outweigh the complications this approach creates for contractors and throughout the construction period.

9.3.8 HOT Issues

HOT lanes have many of the same issues as noted above. Additionally, there are a number of unique concerns. For one, HOT lanes may involve the introduction of tolls for the first time. This may require DOTs to establish new legal and institutional structures and operational capabilities before HOT lane projects can actually be implemented. They may also introduce unfamiliar project financing and operational approaches. Most importantly, they introduce public relations challenges that have the potential to bring HOT lane initiatives to an abrupt halt at nearly any stage of their development (5).

Several other important choices face transportation officials and policy makers as HOT lane projects become more clearly defined. These decisions can have repercussions on design, as well as equity issues and are likely to include (5):

- Eligibility of vehicles. What size and type of vehicles should be eligible to use the HOT lane? If demand exceeds supply, how should users be selected?

- Toll collection. How should the toll collection program be administered?

- Government agency (if so, which one?) or a private contractor under government contract?

- Toll collection technology. Should the project use electronic toll collection or a permit decal system?

- Intermediate access. What frequency of access for buy-in vehicles should be permitted?

9.4 Examples

Information on the numerous freeway HOV implementations across the nation can be found at the Federal Highway Administration's High Occupancy Vehicle website, www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/travel/traffic/hov/index.htm. Two case studies – involving a change in occupancy requirements and HOT lanes – are described below.

9.4.1 El Monte Busway

Opening in 1973, the El Monte Busway on the San Bernardino (I-10) Freeway is the oldest high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) facility in the Los Angeles area. In 1999, the California Legislature approved Senate Bill 63 (SB 63), lowering the vehicle-occupancy requirement on the El Monte Busway from three persons per vehicle (3+) to two persons per vehicle (2+) full time. The legislation directed the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) to make this change on January 1, 2000 as part of a temporary demonstration project, which was to extend until June 30, 2001. The legislation also required Caltrans to monitor and analyze the effect of this change on the operation of the freeway and the Busway. Based on the operational effects of the change, as documented in the Caltrans operational study (as summarized below), new legislation was passed increasing the vehicle-occupancy requirement back to 3+ during the morning and afternoon peak periods and maintaining the 2+ requirement at all other times, effective July 24, 2000.

The Caltrans monitoring program tracked travel speeds, vehicle volumes, and person movement on both the Busway and the general-purpose freeway lanes. Conditions prior to implementation of SB 63, during the 2+ demonstration, and after the change to the 3+ peak/2+ off-peak requirements were monitored by Caltrans. The Caltrans assessment focused on the morning and afternoon peak periods, when demands on the freeway system are greatest and traffic volumes are highest. Further, the analysis focused on the peak direction of travel during these time periods. The results are addressed in Reference 8 and summarized below.

Overall, lowering the vehicle-occupancy requirement from 3+ to 2+ full time had a detrimental affect on the Busway. At the same time, significant improvements were not realized in the general-purpose freeway lanes. The major negative effects on the Busway and the neutral effects on the general-purpose lanes are highlighted below.

9.4.1.1 Travel Speeds

Peak hour travel speeds in the Busway were negatively effected during the 2+ demonstration. Travel speeds in the Busway declined from freeflow conditions at 65 mph to approximately 20 mph in the morning westbound direction. In the afternoon eastbound direction, travel speeds on the Busway decreased from 65 mph to 27 mph during the first month of the demonstration and then increased to 40 mph for the duration of the test.

A significant corresponding increase in travel speeds did not occur in the general-purpose lanes. Travel speeds in the morning westbound direction increased from 25 to 37 mph on the freeway lanes during the first month of the 2+ demonstration, but decreased to 23 mph for the remainder of the operation. In the afternoon, eastbound peak hour freeway travel speeds increased from 32 to 40 mph during the demonstration.

Travel speeds on both the Busway and the freeway lanes returned to close to pre-demonstration levels with the implementation of emergency legislation, AB 769, and the return to the 3+ occupancy requirement during weekday peak-periods. Travel speeds on the Busway increased to 45 mph in the morning and 55 mph in the afternoon peak hours. Although lower than the pre-demonstration 65 mph, both of these speeds represent generally freeflow conditions. Travel speeds in the general-purpose lanes were slightly lower than the pre-demonstration speeds at 20 mph and 28 mph for the morning and afternoon peak hours, respectively.

9.4.1.2 Vehicle Volume and Persons per Hour per Lane

Examining these two measures together is important, as vehicle volumes may increase as the result of a change in the vehicle-occupancy requirement, but the total number of people being carried may decline or may increase at a much lower rate.

- The number of vehicles on the Busway in the morning peak hour increased from 1,100 to 1,600 during the 2+ demonstration, but the number of persons carried declined from 5,900 to 5,200. Thus, more vehicles carrying fewer people were on the Busway. Trends in the afternoon peak-period were different with hourly vehicle volumes increasing from 990 to 1,500 and person volumes increasing from 5,100 to 5,600.

- Vehicle volumes in the general-purpose lanes increased slightly or remained relatively constant over the three time periods, as did the number of persons per hour per lane. Thus, lowering the vehicle-occupancy rate on the Busway, and the subsequent increase in 2+ carpools on the Busway, did not have a corresponding affect of lowering vehicle volumes in the freeway lanes. The increase in vehicles may have resulted from latent demand in the corridor, with commuters diverting from other routes.

9.4.1.3 Public Transit Connections

Buses have always been a key element of the El Monte Busway. Lowering the vehicle-occupancy requirement to 2+ had a significant effect on bus operations. The increase in the number of two-person carpools, which caused congestion on the Busway, resulted in lower bus operating speeds, longer bus travel times and reduced on-time performance, increased service overtime and operating costs, and increases in customer complaints. For example:

- The slower operating speeds resulted in longer bus travel times and reduced on-time performance. Schedule adherence and on-time performance dropped from an average of 88 percent in the fall of 1999 to 48 percent in May 2000. The consistent 20-minute travel time savings provided to bus passengers over vehicles in the general-purpose lanes was lost during the 2+ demonstration.

- The slower bus operating speeds, longer travel times, and reduced on-time performance also caused declines in service productivity. Bus operators finishing their runs late were frequently not able to return for a second trip in the corridor. To fill these voids and to maintain schedules, extra buses and operators had to be dispatched when available. At some points during the demonstration, as many as 10 extra buses and operators were staged in the downtown area to help ensure that trips were not missed and schedules were maintained.

- The affected transit agency estimated that the personnel and fuel costs associated with providing these extra buses were approximately $1,250 per weekday. If the 2+ requirement had been continued, the annual cost of providing the additional buses would have been approximately $325,000.

9.4.1.4 Enforcement and Vehicle-Occupancy Violations

The changes in vehicle-occupancy levels significantly affected the violation rates on the Busway as shown below.

| Time Period | ||

|---|---|---|

| Busway AM Peak-Period | Busway PM Peak-Period | |

| Before January 2000 | 7% | 2% |

| January 1 – July 24, 2000 | 1% | 1% |

| Immediately after July 24, 2000 | 41% | 56% |

| December 2001 | 4% | 9% |

The violation rates declined during the 2+ demonstration, as 2+ person carpools which would previously have been cited became authorized users. The violation rates increased significantly during the early phase of the 3+/2+ operations. Extra enforcement and more visible enforcement were not provided during the initial 3+/2+ operation. As a result, it appears that many 2+ carpools continued to use the lane during the 3+ peak-period. In response to concerns over these high violation rates, CHP undertook an aggressive enforcement program in January 2001. Elements of the program including briefings for all CHP shifts, press releases and radio broadcasts highlighting the correct occupancy requirements, announcing increased enforcement of the rules, and four weeks of enforcement saturation with extra offices assigned to the Busway. These efforts resulted in the violation rates returning to levels similar to those before the 2+ demonstration.

9.4.2 San Diego I-15 Corridor

The I-15 FasTrak involved the conversion of an underutilized preexisting eight-mile 2-lane HOV facility to a peak-period reversible HOT. The project is sponsored by the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG), the local metropolitan planning organization (MPO), which has earmarked a significant portion of the revenues derived from the HOT lane to fund transit improvements in the I-15 corridor. Key operational attributes include (5):

- The lanes operate only during peak hours in the direction of the commute. From 5:30 AM to 11 AM, all vehicles in the HOT lanes travel southbound; from 11:30 AM to 7:30 PM, all vehicles travel northbound.

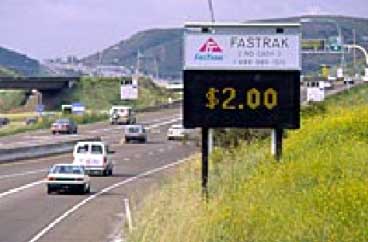

- On normal commute days, the toll ranges between $0.50 and $4.00, depending on current traffic conditions; although tolls may be raised up to $8.00 in the event of severe traffic congestion. To maintain free-flow on the FasTrak lanes at all times, toll rates are adjusted every 6 minutes in response to real-time traffic volumes. The actual toll at any given time is posted on roadside CMS signs (shown below) to inform drivers of the current price for using the lanes.

- Customers must have a FasTrak account and transponder to use the HOT lanes. Motorists enter the HOT lanes at normal highway speeds. Toll collection occurs when the motorist travels through the tolling zone at the entrance.

- To preserve the carpooling incentives that existed with the original HOV lanes, carpools and other vehicles with two or more occupants may always use the FasTrak lanes for free.

The I-15 HOT lane initiative also included early and aggressive efforts to assess public opinion and potential usage of the lanes before the facility was launched. Additionally, the implementing agency SANDAG also has paid close attention to marketing issues throughout project implementation and operational phases. The SANDAG I-15 FasTrak Online website (http://argo.sandag.org/fastrak/library.html) provides full documentation of the supporting studies that were used to formulate tolling schedules, marketing plans and promotional materials.

Reference 5 provides additional details on the lessons learned form the I-15 HOT lanes, including:

- Team effort among key stakeholders is important for ensuring consensus and maintaining momentum from project planning to implementation.

- A local, influential political champion may explain why the I-15 project was implemented while other value pricing proposals have not been realized.

- Strong community outreach efforts to citizens, community groups, and elected officials must continue throughout project planning, implementation and operation to communicate information regarding project goals, plans, progress and benefits.

- Detailed project agreements may be needed to specify the roles and responsibilities of participating agencies and other parties. These should be arranged as early in the project process as possible, leaving some flexibility for unexpected issues.

- Dynamic tolling involves significant technical and administrative complexities. The project schedule should budget time to plan and implement new technologies, institutional arrangements and administrative procedures.

- Reciprocity with other toll agencies is important. Data compatibility and revenue transfer are key issues to work out.

9.5 References

1. HOV System Manual: NCHRP Report 414; National Academy Press; Washington D.C.; 1998

2. WSDOT Report on HOV Operations

3. Fuhs, Chuck and Jon Obenberger. HOV Facility Development: A Review of National Trends. Paper on the 2002 Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting CD ROM, January 2002.

4. Turnbull, K.F. Effective Use of Park-and-Ride Facilities. Synthesis of Highway Practice 213, National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, 1995.

5. "A Guide for HOT Lane Development"; Perez, B. & Sciara, G.; FHWA; 2001

6. Turner, S. "Video-Based HOV Enforcement System To Be Tested," Urban Transportation Monitor. April 26, 1996, pp 3.

7. Billheimer, John, Moore, J.B., and Stamm, Heidi. HOV Marketing Manual – Marketing for Success, Federal Highway Administration, 1994

8. Turnbill, K.; "Affects of Changing HOV Lane Occupancy Requirements: El Monte Busway Case Study"; Texas Transportation Institute; FHWA-OP-03-002; June 2002

9. High Occupancy Vehicle Lanes Enforcement Survey. Prepared for Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County. Texas Transportation Institute, Texas A&M University System, College Station, TX, 1988.

10. Guide for the Design of High Occupancy Vehicle Facilities. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. 1992.

11. Fuhs, C.A. High-Occupancy Vehicle Facilities: A Planning, Design, and Operation Manual. Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc., 1990.