Federal-Aid Highway Program Guidance on High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Lanes

September 2016

Chapter II Concept, Background, and History

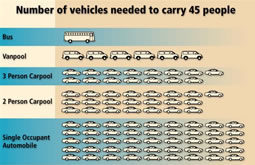

Graphic showing that one bus, or six vanpools, or 15 3+ carpools, or 22 2+ carpools, or 45 single-occupant vehicles, are necessary to transport 45 people.

Concept

The primary purpose of an HOV lane is to increase the total number of people moved through a congested corridor by offering two kinds of incentives: a savings in travel time and a reliable and predictable travel time. (Note: hereafter, the term "HOV lane" is intended to cover both HOV and HOT situations, primarily due to the fact that HOT lanes inherently include an element of HOV use for qualifying vehicles. The term "HOT lane" may be called out for particular emphasis when the specific description of that facility is necessary.) Because HOV lanes carry vehicles with a higher number of occupants, they may move significantly more people during congested periods, even when the number of vehicles that use the HOV lane is lower than on the adjoining general-purpose lanes. In general, carpoolers, vanpoolers, transit users, and single-occupant users paying to use HOT lanes, are the direct beneficiaries of HOV and HOT lanes, whereas, motorists and passengers in the adjacent general purpose lanes are indirect beneficiaries, due to the reduction of vehicles in those lanes necessary to move said motorists and passengers in the HOV lanes.

HOV facilities have proven to be effective enhancements to the transportation system in many metropolitan areas. These facilities are most appropriate and are most needed in corridors with high levels of travel demand and traffic congestion. In these situations, HOV facilities can provide the travel times saving and improved travel time reliability necessary to encourage commuters to change from driving alone to using transit services, vanpools, and carpools. HOV lanes work best where significant roadway congestion during the peak periods occurs and HOV support facilities such as park and ride lots are provided. Experience with HOV lanes from around the country has shown a positive relationship between ridership and travel time savings, suggesting that, as congestion grows, the travelers' willingness to carpool or ride on a bus that uses an HOV lane also grows.

HOT Facilities in the U.S.

In locations where HOV lanes are underutilized or where excess capacity on the HOV facility exists, conversion to HOT lanes is suggested as a way to increase use and to provide more choice to drivers. HOT lanes allow single-occupancy vehicles (SOVs) or lower-occupancy vehicles (LOVs), that is, vehicles with a number of occupants lower than the posted vehicle occupancy restrictions, to use an HOV lane for a fee, while maintaining free travel for qualifying HOVs.

To maximize the congestion-reducing benefits of an HOT lane facility, the toll charged should vary by time of day and/or level of congestion. Tolls can be varied by time of day, monthly, or quarterly based on historical highway use, or can vary dynamically over the course of the day based on real-time traffic conditions. The use of real-time or historically based variable tolling on HOT lanes may have a significant positive effect on traffic flow. For example, the MnPASS HOT lanes in Minneapolis vary the toll rates using real-time pricing, with the rates being updated every three minutes to reflect the amount of traffic on the road.

Picture of MnPass facility in Minnesota stating "Car pools, buses and motorcycles (are) Free" while displaying toll rates for non-exempt vehicles.

Effective management of an HOV lane involves developing and using an HOV operation and enforcement plan, along with a performance-monitoring program. Accurate and possibly real-time information about the performance of the HOV lanes, the general-purpose freeway lanes, and other supporting services and facilities is particularly useful. The information provided through an HOV monitoring program is also critical for assessing the impact of possible changes in vehicle-eligibility requirements, vehicle-occupancy levels, and operating hours.

Background

The development of HOV facilities has evolved since the early 1970s. The bus-only lane on the Shirley Highway in Northern Virginia/Washington, D.C. and the contraflow bus lane on the approach to New York-New Jersey's Lincoln Tunnel pioneered the freeway HOV application in this country. Many of the initial HOV lanes were bus-only applications or allowed buses and vanpools. In an effort to maximize use, carpools became the dominant use group on most projects during the 1970s and 1980s. The vehicle-occupancy requirements for carpools have also evolved over time. A 3+ occupancy level was initially used on many projects, but most current facilities use a two-person per vehicle (2+) carpool designation. Today, there are close to two dozen states and Puerto Rico that have some permutation of HOV, HOT, or "Express Lanes", et al.

Congestion is recognized to be a growing problem, particularly in American urban areas. The U.S. has close to four million miles of roads, bridges, and highways to support a wide variety of economic and social activity. However, over time the demands on this infrastructure have outstripped its capacity. While the miles of urban roadways built have increased by nearly 65 percent since 1980, vehicle miles traveled on urban roadways increased by about 150 percent. As a result, traffic in most metropolitan areas has become increasingly congested, costing both time and fuel.

Picture showing "FastTrak" toll of $1.50, and indicating a "no cash" (i.e., all electronic) collection method.

To address the continued growth of congestion, cities and States have shown a growing interest in managing travel demand by setting prices for road use during peak periods. Among the various pricing schemes, HOT lanes have proven to be of particular interest because they not only address congestion in the short run, but they also demonstrate the benefits of more aggressive pricing strategies. And, they offer the customer travel time savings and a guaranteed level of service. HOT lanes are part of a broader managed lanes concept that employs market forces to help optimize use of the facilities.

Many of the HOT lanes implemented in the U.S. were piloted under the Value Pricing Pilot Program (VPPP). Prior to the passage of MAP-21's precursor, SAFETEA-LU, the VPPP was the only program under which HOT lanes could be implemented. In general, the VPPP allowed up to fifteen States to evaluate the feasibility and deployment of innovative pricing strategies, including HOT lanes as experimental pilot projects on the Interstate System. However, the SAFETEA-LU law of 2005 mainstreamed the authority to create HOT lanes and since then all States are allowed to create HOT facilities, although as noted further above, no more than approximately two dozen have these facilities. This concept continued in MAP-21, and again, in the FAST Act, wherein, States are now able to implement HOT lanes under 23 U.S.C. 166. However, under certain circumstances (typically grandfathered clauses), FHWA may grant a State authority to toll HOV lanes under the VPPP. Although this document addresses the conversion of HOV lanes to HOT lanes, States can also create HOT lanes by building new lanes where no conversion would be required.

Previous | Next