Houston Managed Lanes Case Study: The Evolution of the Houston HOV System

CHAPTER TWO—EVOLUTION AND USE OF THE HOUSTON HOV LANE SYSTEM

Development and Operation of the HOV Lane System

As noted previously, traffic congestion was a significant concern in Houston during the 1970s. The Texas Highway Department (THD) was planning expansions to many freeways and examining possible improvements to others. At the same time, the privately-owned bus company was encountering serious financial difficulties. As a result, service levels were low and buses were in poor conditions.

In the early 1970s, the City of Houston was exploring options for establishing a public transit authority. A long-range transit plan was prepared, which included an extensive rail system and HOV lanes on some freeways. This plan was the basis for a 1973 ballot measure to establish the Houston Area Rapid Transit Authority (HARTA). Although supported by the City Council and community leaders, voters defeated the HARTA proposal. In 1974, the City purchased the privately-owned bus company and established the Office of Public Transportation (OPT).

The OPT began an aggressive program to upgrade the bus system. The Office developed a strong working relationship with the THD Houston District to explore and implement congestion reducing strategies. OPT and THD shared a common interest in addressing increasing levels of traffic congestion by encouraging greater use of buses, vanpools, and carpools. THD was concerned about improving travel conditions on congested freeways and OPT was interested in methods to move buses through traffic more efficiently and to improve services levels and the image of the bus system. Using a federal Service and Methods Demonstration (SMD) grant, the OPT and THD examined the potential of freeway HOV lanes, which were a relatively new concept at the time. A contraflow lane demonstration project on the North (I-45 North) Freeway was recommended to test the HOV concept.

A contraflow HOV lane uses a lane in the off-peak direction of travel for HOV travel in the peak direction. Contraflow lanes are appropriate for corridors with high directional splits, such as 60 percent of traffic in the peak direction and 40 percent in the off-peak direction. The excess capacity in the off-peak direction of travel is used for HOVs moving in the peak direction. The I-45 N corridor had a high directional split and travel in the peak direction was very congested. Thus, the corridor provided the right conditions for the demonstration.

The demonstration project included a nine-mile contraflow HOV lane, park-and-ride lots, freeway ramp metering, and contracted bus service. The demonstration was funded through a variety of sources, including federal highway and transit programs, state highway funds, and local sources. The unique blend of financing provides an indication of the cooperation among agencies and the willingness to take creative approaches. This unique mix of financing and interagency cooperation continued as important characteristics of future HOV projects.

The development and operation of the contraflow lane and subsequent HOV facilities was guided by a series of agreements between the two agencies. These institutional arrangements are discussed in Chapter Three. Construction and operation of the contraflow demonstration project also represented a joint effort. The THD, which became the State Department of Highways and Public Transportation (SDHPT), was responsible for construction management, engineering, and inspection, and OPT administered the funds for contractor payments and reimbursement of SDHPT.

During the development of the contraflow lane the city continued to work toward establishing a regional transit agency. In 1978, voters approved the creation of the Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County (METRO) and the dedication of one percent of the local sales tax to fund the agency. The 1978 Regional Transit Plan, which identified the projects METRO would pursue, included HOV facilities in most freeway corridors, as well as rail transit. The HOV facilities included in this plan have been incorporated and refined in METRO, TxDOT, and Houston-Galveston Area Council (HGAC) plans over the years. With the creation of METRO, OPT was dissolved in 1979.

The contraflow lane began operation in August 1979. Figure 1 shows the location of the contraflow lane. The lane operated from 5:45 a.m. to 8:45 a.m. in the inbound direction toward downtown and from 3:30 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. in the outbound direction. The contraflow lane was created by taking the inside freeway lane in the off-peak direction of travel for use by buses and vanpools traveling in the peak-direction. The lane was separated from opposing traffic by plastic pylons, which were set up and removed by METRO crews each morning and afternoon.

Due to safety concerns, only buses and authorized vanpools were allowed to use the contraflow lane. Figure 2 highlights the operation of the lane. To become eligible to use the lane, vanpool drivers had to register and complete training provided by METRO. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, many large downtown employers subsidized vanpools for their employees in response to the Arab Oil Embargo in 1979. Enforcement of the lane was initially contracted to the Houston Police Department. METRO established its own transit police force in 1982 and assumed enforcement duties of the contraflow lane at that time. METRO also provided wreckers at strategic locations along the lane to deal with any accidents or incidents.

Figure 1. Location of I-45 North Contraflow Lane.

Figure 2. I-45 North Contraflow Lane.

Use of the contraflow lane exceeded projections. Some 8,000 bus riders and vanpoolers used the lane on a daily basis during the first few years of the project. During the morning peak hour, the lane carried nearly as many people as the adjacent two freeway lanes. A 3.3-mile concurrent flow lane upstream from the entrance to the contraflow lane was opened in 1981. Use levels increased to a high of 15,000 riders per day with this improvement.

The success of the demonstration project resulted in a permanent HOV facility on the North Freeway and the consideration of HOV lanes on other freeways. The demonstration proved that commuters would change from driving alone to taking the bus or riding in a vanpool. Survey results indicate that some 35 to 39 percent of bus riders and 30 to 42 percent of vanpoolers previously drove alone.

As a result of the demonstration, a reversible HOV lane was added to plans for upgrading and expanding the North Freeway. The permanent HOV lane was a one-lane barrier separated reversible facility located in the center median of the freeway. A number of factors influenced the use of this design, including limited right-of-way, increased safety due to barrier separation, and the directional split of travel in the corridor. In September of 1984, the first segment of the permanent HOV lane opened and operation of the contraflow lane ceased.

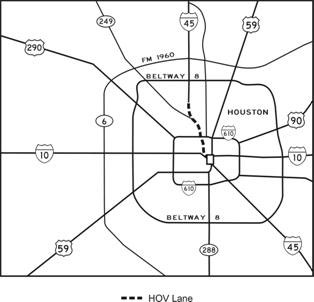

The development of the second HOV lane in Houston took advantage of a planned improvement project. Plans to repair and overlay a 10-mile segment of the Katy Freeway were moving forward in the late 1970s, with a major reconstruction effort anticipated in the future. An HOV lane on the Katy Freeway had been identified in the 1978 Regional Transit Plan. To take advantage of the opportunity presented by the repair project, the design of the HOV lane was expedited and the overlay project was delayed slightly. Working jointly, the SDHPT and METRO completed the design and construction process, including obtaining the necessary federal approvals, and the first 4.7-mile segment of the Katy HOV lane was opened in October of 1984. Figure 3 shows the location of the Katy HOV lane and the HOV system in 1985.

The lane initially operated inbound from 5:45 a.m. to 9:30 a.m. and outbound from 3:30 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. Operating hours were extended to 5:45 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. in 1986. Following the vehicle eligibility requirements in use on I-45 North, only buses and vanpools were initially allowed to use the Katy HOV lane. Only 66 vanpools and 20 buses, for a total of 86 vehicles, used the lane during the morning peak hour with these requirements. To address this low use, the lane was open to authorized 4+ carpools in 1985. The occupancy requirement was dropped to 3+ carpools later in 1985 and to 2+ carpools in 1986. Table 1 highlights the initial changes in vehicle eligibility and vehicle-occupancy levels and corresponding use levels.

Figure 3. 1985 Houston HOV Lane System.

| Vehicle Eligibility and Vehicle-Occupancy Requirements | Date (Time after Opening) | AM Peak Hour HOV Lane Vehicle Volumes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carpools | Vanpools | Buses | Total | ||

| Buses and Authorized Vanpools | October 1984 | – | 66 | 20 | 86 |

| Buses, Authorized Vanpools and Authorized 4+ Carpools | April 1985 (6 months) |

3 | 68 | 25 | 96 |

| Buses, Authorized Vanpools, and Authorized 3+ Carpools | September 1985 (1 year) |

53 | 59 | 31 | 143 |

| Buses, Vanpools, and 2+ Carpools | November 1986 (2 years) |

1,195 | 38 | 32 | 1,265 |

| November 1987 (3 years) |

1,453 | 21 | 37 | 1,511 | |

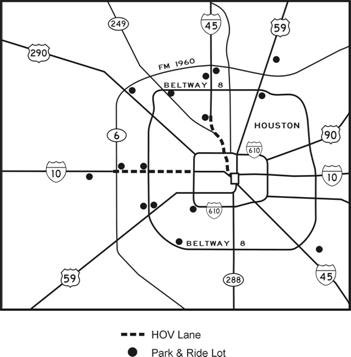

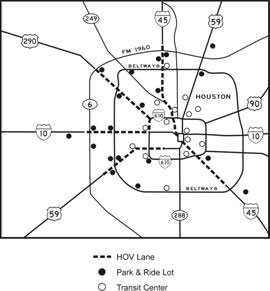

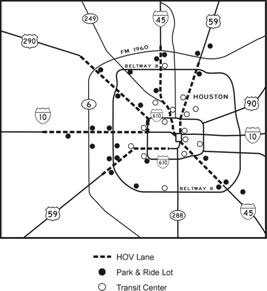

The HOV system expanded significantly from 1985 to 2003. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the growth in the HOV system over this 18-year period. METRO and the renamed Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) continued to work cooperatively on the development and operation of the HOV system. Funding from METRO, TxDOT, FHWA, and FTA was used for different parts of the system.

Figure 4. 1995 Houston HOV Lane System.

Figure 5. 2003 Houston HOV Lane System.

By 2003, some 100 miles of HOV lanes are in operation in six freeway corridors. The main elements of the HOV system – the HOV lanes, park-and-ride lots, transit centers, direct access ramps, and express bus service – are highlighted next.

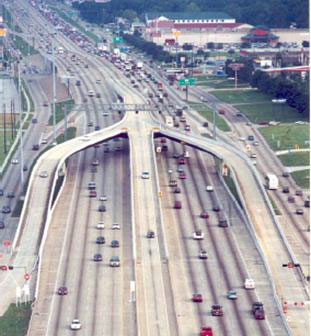

HOV Lanes. As Figure 6 illustrates, the HOV lanes are primarily one-lane, reversible, barrier-separated facilities, located in the median of six freeways. A short two-lane, two-direction section exists on the Northwest (US 290) Freeway. A two-way facility, with one lane in each direction of travel, is in operation on the Eastex (US 59) Freeway. A concurrent flow HOV lane is in operation on the Katy Freeway, leading to the reversible lane. As noted previously, the design used for the HOV lanes was influenced by a number of factors. These factors include limited right-of-way in the freeway corridors, providing a safer operating environment through the use of barriers, and the directional splits in the corridors.

The lanes operate in the inbound direction from 5:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. and in the outbound direction from 2:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. The lanes are closed from Noon to 2:00 p.m. to reverse operations and are closed to all traffic at other times. A 2+ vehicle-occupancy requirement is used on all the HOV facilities, except the Katy and the Northwest. These two HOV lanes have a 3+ occupancy requirement from 6:45 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m., due to congestion occurring at the 2+ level. The Quick Ride value-pricing project operates on these two lanes, allowing participating 2+ carpools use of the lane for a $2.00 per trip fee. This project is described later in this chapter.

Figure 6. Katy (I-10 West) HOV Lane.Park-and-Ride Lots. A total of 28 park-and-ride lots and four park-and-pool lots are located in the six corridors with HOV lanes. The larger park-and-ride lots have direct access to the HOV lanes and transit stations with passenger amenities. There are spaces for between 900 and 2,500 automobiles at 19 of the lots. The number of parking spaces at lots in each corridor range from slightly over 3,000 to almost 7,500. Figure 7 illustrates the Fuqua park-and-ride lot and transit station along the Gulf (I-45 South) Freeway.

Figure 7. Fuqua Park-and-Ride Lot.Transit Centers. The park-and-ride lots have transit stations with covered passenger waiting areas and other amenities. Transit centers without park-and-ride lots or with only small lots are located at strategic transfer points. Figure 8 illustrates an example of a transit center with direct access to the HOV lanes.

Direct Access Ramps. As Figure 9 illustrates, direct access ramps connect the major park-and-ride lots and transit stations to the HOV lanes. These ramps provide travel time savings for buses using the HOV lanes and enhance the safe operation of both the HOV lanes and the freeways. Use of the direct access ramps is restricted to buses, carpools, and vanpools during operating hours. The ramps are closed during non-operating periods. Carpools and vanpools can access the ramps and the HOV lanes through the lots. The direct access ramps provide significant travel time savings for buses and other HOVs. The 1990 opening of the direct access ramp linking the Northwest Station park-and-ride lot with the Northwest HOV lane provided travel savings of 14 minutes for vehicles entering and exiting the HOV lane. Prior to the ramp opening, HOVs had to travel local streets, enter the freeway, and merge across the general-purpose lanes to enter the HOV lane. Use levels increased after the ramp opened. As Figure 9 highlights, direct HOV lane access ramps are also provided at selected entry and exit points.

Figure 8. Direct Access Ramp to Kuykendahl Park-and-Ride Lot.

Figure 9. Direct Access Ramp.Express Bus Service. METRO provides a high level of bus service in each corridor, with frequent trips from the major park-and-ride lots. Over-the-road coaches are operated on many routes, as are articulated buses. Although there is not direct evidence linking increased ridership to use of the coaches, surveys of bus riders indicate support for their use and support for frequent service. The HOV lanes and express bus services are oriented primarily in a radial direction, with downtown Houston as the major destination. The express bus system has evolved over the years, however, providing service to major activity centers such as the Texas Medical Center (TMC), Greenway Plaza, and the Post Oak/Galleria area. More recently, reverse commute services have been added in some corridors, taking advantage of buses in the general-purpose lanes deadheading back to park-and-ride lots.

Rideshare Services and Other Supporting Activities. METRO provides rideshare services in the Houston area. METROís RideShare program includes a number of elements to help individuals form carpools and vanpools. Rideshare matching services are available by telephone and on-line through METROís Internet site. The METROVan program helps commuters form vanpools and provides vans for their use. METROVan is co-sponsored by HGAC, allowing METRO to provide vanpools outside the METRO service area. METROís corporate RideSponsor program focuses on encouraging employees to commute to work by bus, carpools, or vanpools. The program provides computerized ridematching services, vanpools, and employer outreach. Corporate RideSponsors are eligible for discounted bus passes for their employees.

Use of the HOV Lane System

METRO and TxDOT sponsor ongoing monitoring of the Houston HOV system. A multi-year TxDOT research study provided an annual assessment of the system for many years. METRO supports ongoing data collection and evaluation efforts. The monitoring program focuses primarily on HOV and freeway vehicle volumes, bus ridership levels, vehicle occupancy levels, travel times in the HOV lanes and the freeway lanes, and incident data. Periodic surveys of bus riders, carpoolers, and vanpoolers using the HOV lanes, and motorists in the general-purpose lanes have been conducted. Highlights from these and other ongoing efforts are summarized here. More detailed information is available in the reports provided in the references.

Use Levels. Table 2 presents key information on use of the Houston HOV lanes. In 2003, some 212,079 passengers used the HOV lanes on a daily basis. Buses carried 43,225 passengers, vanpools accounted for 2,500 riders, carpools had 74,867 occupants, and 407 motorcycles used the lanes daily. Morning peak-hour utilization levels range from approximately 1,000 vehicles on the Katy HOV lane to 1,551 on the Northwest HOV lanes.

Table 2. 2003 Houston HOV Lane Parameters and Weekday Utilization Data Katy

(I-10 W)North

(I-45 N)Gulf

(I-45 S)Northwest

(US 290)Southwest

(US 59 S)Eastex

(US 59 N)Length 13 13.5 12.1 13.5 12.2 14.8 Opening Date 1984 1984 1988 1988 1993 1999 Number HOV/General-Purpose Lanes 1/3 1/4 1/4 1/3 1/5 HOV Lane Person Volume AM Peak-Hour – Total 4,776 5,736 4,818 4,077 5,330 826 Buses 1,710 2,290 1,545 1,260 1,890 195 Carpools/Vanpools 3,001 3,223 3,098 2,794 3,249 626 Motorcycles 25 3 5 23 11 5 Daily – Total 28,585 26,325 18,488 20,566 23,396 5,841 HOV Lane Vehicle Volume AM Peak-Hour – Total 1,350 1,405 1,457 1,273 1,548 280 Buses 40 43 29 27 36 4 Carpools/Vanpools 1,283 1,350 1,418 1,223 1,495 271 Motorcycles 18 3 5 23 11 5 Daily – Total 9,778 7,386 5,596 7,332 6,972 1,357 AM Peak-Hour Average Vehicle Occupancy HOV Lane – Buses Only 42 53 53 47 52 48 HOV Lane – Carpools/Vanpools Only 2.30 2.30 2.20 2.24 2.19 2.18 Total HOV Lane 3.22 4.08 3.30 3.20 3.44 2.95 General-Purpose Lanes 1.12 1.02 1.07 1.05 1.07 1.05 Corresponding person volumes in the morning peak hour average between 3,424 on the Gulf HOV lane and 4,836 on the North HOV lane. The HOV lanes account for 40 percent of the morning peak hour total person movement on three of the freeways. The AM peak hour is defined as the hour with the highest vehicle volumes. As a result, the peak hour may vary by HOV lane.

Vehicle-occupancy requirements were adjusted on two HOV lanes due to high levels of use. By 1988, morning peak hour vehicle volumes on the Katy HOV lane were frequently approaching or exceeding 1,500 vehicles. The travel time savings and the trip time reliability provided by the lane and expected by users began to degrade with volumes of 1,500 vehicles in the morning peak hour. HOV lane users, especially bus riders, began to complain over the degradation in service.

A number of alternatives were considered by METRO staff to address the problem of too many vehicles during the morning peak hour. Options considered included requiring authorization for 2+ carpools, metering access, increasing vehicle-occupancy levels, requesting voluntary changes in travel times, and not making any changes. An attempt was made to encourage voluntary changes in travel times through postcards to vanpoolers and carpoolers. This approach did not result in significant changes in peak-hour vehicle volumes.

A policy-level decision was made by both agencies to increase the vehicle-occupancy requirement from 2+ to 3+ during the period from 6:45 to 8:15 a.m. The 2+ requirement was maintained at other times. This change was implemented on very short notice in October 1988.

Table 3 highlights the changes in vehicle volumes immediately after the change to the 3+ requirement in 1988 and the growth in 3+ carpools over the next eight years. The morning peak hour carpool volume dropped from some 1,450 to 510 vehicles immediately after the change, representing a 65 percent reduction. Total AM peak hour vehicle volumes – carpools, vanpools, and buses – dropped from 1,511 to 570, a 62 percent reduction. Person volumes declined by 33 percent during the AM peak hour. Although vehicle and person volumes declined, AM peak hour average vehicle occupancy (AVO) increased from 3.1 prior to the change to 4.5 five months after the change.

Vehicle volumes during the 6:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. peak-period declined by some 14 percent. Two person carpools declined by some 41 percent and 3+ carpools increased by 68 percent. Bus ridership grew by eight percent. Based on survey results, it appears that some two person carpools shifted their travel to earlier time periods and some changed their travel routes to use the newly opened Northwest HOV lane, which had a 2+ requirement.

Table 3. Change to 3+ Occupancy Requirement on the Katy HOV Lane Vehicle Eligibility and Vehicle-Occupancy Requirements Date (Time after Opening) AM Peak Hour HOV Lane Vehicle Volumes Carpools Vanpools Buses Total Buses, Vanpools and 3+ Carpoolsa October 1988

(4 years)510 24 36 570 March 1989

(41/2 years)660 28 40 728 December 1989

(5 years)611 19 37 667 1996

(12 years)858 19 33 910 The time period for the 3+ restriction on the Kay HOV lane has been modified over time. In May 1990, the 3+ period was shortened to 6:45 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. In September 1991, the 3+ restriction was implemented in the afternoon peak hour from 5:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. A 3+ restriction was also implemented from 6:45 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. on the Northwest HOV lane in July 1999 in response to congestion levels similar to those experienced on the Katy HOV lane.

Bus Operating Speeds and Schedule Times. The HOV lanes and direct access ramps have significantly increased METRO bus operating speeds. The peak hour bus operating speeds have almost doubled, from 26 mph to 54 mph, resulting in significant reductions in bus schedule times. Examples of reductions in the morning peak hour schedule time for buses from park-and-ride lots to downtown Houston include from 45 to 24 minutes from the Addicks park-and-ride lot on the Katy HOV lane, from 40 to 25 minutes from the Edgebrook park-and-ride lot on the Gulf HOV lane, and from 50 to 30 minutes from the Northwest Station park-and-ride lot on the Northwest HOV lane.

Travel Time Savings. The HOV lanes provide travel time savings for buses, vanpools, and carpools. Morning peak hour travel time savings range from approximately 2 to 22 minutes on the different HOV lanes. The Northwest Freeway HOV lane generally provides the largest travel time savings of about 22 minutes. The Katy HOV lane averages between 17 and 20 minutes, the North 14 minutes, and the Gulf and Southwest between 4 and 2 minutes. In addition, the HOV lanes provide more reliable trip times to carpoolers, vanpoolers, and bus riders.

Park-and-Ride Lots. Approximately 32,293 spaces are provided at 28 park-and-ride lots associated with the HOV lanes. An additional 1,377 spaces are located at four park-and-pool lots. METRO buses serve the park-and-ride lots, while the park-and-pool lots provide staging areas for carpools and vanpools. In 2003, the overall occupancy levels at the individual facilities ranged from about 10 percent at some park-and-pool lots to 100 percent at well-used park-and-ride lots. Table 4 highlights the growth in the number of park-and-ride lots and use levels from 1980 to 2003. From 1980 to 1990, the number of park-and-ride lots doubled from 10 to 20. The number of available spaces increased from 4,070 spaces to 12,626 spaces. Use of the lots grew from 4,070 parked vehicles to 12,626 vehicles. As of 2003, there are 28 park-and-ride lots, with 32,293 spaces. Approximately 54 percent of the available spaces are used on a daily basis. Table 5 highlights the number of park-and-ride spaces, and the occupancy levels by corridor.

Change in Travel Mode. The travel time savings and the improved trip time reliability have influenced commuters to change from driving alone to taking the bus, carpooling, and vanpooling. Periodic surveys of HOV lane users show that between 36 and 45 percent of current carpoolers formerly drove alone, while 38 to 46 percent of bus riders previously drove alone. Surveys conducted in 1988, 1989, and 1990, indicate that the opening of the HOV lanes was very important in their decision to ride a bus for between 54 and 76 percent of the bus riders using the Houston HOV lanes. Between 22 and 39 percent of the respondents also indicated that they would not be riding the bus if the HOV lane had not been opened.

Average Vehicle Occupancy. The HOV system has resulted in an increase in AVO levels in the corridors with HOV lanes. For example, the morning peak-hour AVO increased on the North Freeway from 1.28 in 1978 before the contraflow HOV lane opened to 1.41 in 1996. The morning peak-hour AVO increased on the Northwest Freeway from 1.14 in 1987 prior to the opening of the HOV lane to 1.36 in 1996. The 1996 morning AVO for the HOV lanes ranged from 2.6 to 3.65, compared to 1.02 to 1.12 for the general-purpose lanes.

Table 4. Houston HOV Lane Park-and-Ride Lot Capacity and Utilization Year Number of Lots Number of Spaces Occupancy Percent Occupancy 1980 10 6,414 4,070 63% 1990 20 22,882 12,626 55% 2003 28 32,293 17,564 54% Table 5. Houston HOV Lane Park-and-Ride Lot Capacity and Utilization by Corridor Corridor Number of Lots Number of Spaces Occupancy Percent Occupancy Katy Freeway (I-10 W) 3 5,883 3,489 59% North Freeway (I-45 N) 5 7,313 3,976 54% Gulf Freeway (I-45 S) 4 3,373 2,120 63% Northwest Freeway (US 290) 4 4,615 3,093 67% Southwest Freeway (US 59S) 8 7,311 3,288 45% Eastex Freeway (US 59 N) 4 3,798 1,598 42% TOTAL 28 32,293 17,564 54% Positive Public Perception. Periodic surveys of HOV lane users and motorists in the general-purpose lanes included questions designed to obtain feedback on the general perception toward the HOV lanes and support for these facilities. Between 40 and 81 percent of motorists in the general-purpose lanes on freeways with HOV facilities and one freeway without an HOV lane have responded positively to these surveys that the HOV facilities are a good transportation improvement.

QuickRide Value Pricing Demonstration

In 1996 and 1997 TxDOT and METRO conducted a congestion or priority pricing feasibility study on the Katy Freeway. The study represented one of the congestion pricing pilot projects funded by FHWA under the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA). The name of the pilot project program was changed to priority pricing under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21). The study examined the potential of allowing 2+ carpools to use the HOV lane for a fee during the morning and afternoon peak hours when the 3+ occupancy requirement is in effect.

METRO and TxDOT staff were interested in considering the potential of 2+ HOVs using the lane during the 3+ restricted period for a fee due to the excess capacity available at those times. The pricing demonstration was viewed as a way to increase use of the lane without allowing it to become overly congested as it was in 1988 when the vehicle-occupancy requirement was raised to 3+. The study estimated that approximately 600 additional vehicles could be accommodated in the lane during the peak hour while maintaining free flow operations. Consideration of a potential demonstration reflects the ongoing interest in the part of METRO and TxDOT in maximizing use of the lanes to benefit travelers. Consideration of allowing only 2+ HOVs, rather than single-occupancy vehicles, indicates the commitment of both agencies to maintain the integrity of the HOV lane concept and to provide travel time savings and trip time reliability to HOVs.

A number of key elements were examined during the feasibility study. These included assessing the available capacity and the potential demand at different pricing levels, legal issues, and public reactions. A variety of potential operational strategies were explored, including manual and automated payment techniques. A major question was how many 2+ carpools would use the facility at different pricing levels. This analysis was critical to ensure that the HOV lane did not become congested as a result of a demonstration.

Legal and institutional issues were also examined in the assessment. These concerns included the ability to charge for use of the HOV lane, the ability to enforce fines and penalties associated with not paying the toll, and other policy changes needed to implement the demonstration. The study results indicated that METRO has the authority to charge for use of the lanes under specific conditions, that the fines are enforceable with minor modifications, and that there were no critical policies prohibiting a demonstration.

Like other congestion pricing projects, a critical issue appeared to be public acceptance. As part of the feasibility study, two focus groups were conducted in Houston. One focus group was comprised of commuters who used the Katy Freeway and the other was composed of residents throughout Houston. The focus group participants were somewhat skeptical about the concept. Both groups were also interested in how the revenue from the demonstration would be spent.

Based on a feasibility study, the decision was made to implement a demonstration project to test allowing two-person carpools to use the HOV lane for a $2.00 per trip fee during the 3+ occupancy requirement periods – 6:45 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. METRO applied for a federal demonstration grant for the project, but all of the funds had been allocated. As a result, METRO and TxDOT used funding from Houstonís allocation under the Priority Corridor Program to implement the demonstration. Approval from both the FHWA and the FTA administrators was requested based on action by the METRO Board and the TxDOT Commission. Approval for the demonstration was received from FHWA and FTA administrators. Approval from both federal agencies was needed since funding from both had been used for the Katy HOV lane and supporting elements.

The demonstration, called QuickRide, which uses an electronic toll collection system, was implemented at the end of January 1998. Individuals are required to register for the program and must have an active electronic tag account. By June 1998, 468 QuickRide electronic tags had been issued. In 2000, the demonstration was expanded to include the Northwest Freeway HOV lanes, only in the morning peak hour. As of April 2003, there were 1,476 active QuickRide accounts.

The daily use of the demonstration has grown slowly over time. In 1998, the demonstration averaged 103 daily users on the Katy HOV lanes. By 1999, some 121 participants were using the program daily. Use levels in 2000, 2001, and 2002 remained relatively constant, averaging between 120 and 128. Use levels are higher in the morning on the Katy, with some 68 percent of the daily participants traveling in the lane in the morning peak hour. Some 22 people used the program in the morning peak hour on the Northwest HOV lane in 2000, with use growing to an average of 56 by 2002.

Each enrolled tag generates an average of one tolled trip every four days, producing an average of 115 to 120 total two-person carpool trips during the 1-1/4 morning hours plus the one evening hour. Only 6.5 percent of enrolled tags produced five or more trips per week (out of a maximum of 10). Approximately 25 percent of the tags had never been used as of June 1998. Many of these may belong to two-tag households. Base on an average time savings of 18 minutes, the estimated minimum value of travel time for participating vehicles, which is the sum for both occupants, is $6.57 per hour.

Although use levels have been modest, the demonstration has been successful at allowing an additional user group to use the HOV lanes during the 3+ restricted period. It appears that many enrollees view having an electronic tag as insurance for the occasional need and opportunity to ensure a quick trip, but cannot use the program on a regular basis.

A survey of travelers on the mixed traffic lanes indicated a low level knowledge of the program. Some 55 percent of the respondents thought it was fair, however, 67 percent viewed it as effective for the HOV lanes, and 85 percent perceived a benefit for the regular lanes. While the low QuickRide usage has not resulted in significant changes in person throughput on the freeway, it appears that some 25 percent of the users are forming two-person carpools to participate, compared to only 5 percent of users who appear to be coming from all types of higher-occupancy modes.

Development of Katy Freeway Managed Lanes

Plans for expanding the Katy Freeway began in the late 1990s. The 23-mile corridor carries some 280,000 vehicles a day. The existing cross section in the most congested section from SH 6 to I-610 includes three general-purpose lanes in each direction, the HOV lane, and three lane frontage roads in each direction.

A number of alternatives were examined in the Major Investment Study (MIS), including four special-use lanes in the freeway median. Other options included additional general-purpose lanes and expanding the HOV lanes. The special-use or managed lane option emerged from this study as the preferred alternative. The specific operation of the managed lanes was not defined, but user groups considered included buses, 3+ HOVs, QuickRide HOVs, vanpools, trucks, and long-distance travelers. Other than QuickRide participants, tolling was not considered as an operational strategy. The cross-section for the section between SH 6 an I-610 would include a three-lane frontage road and four main lanes in each direction of travel, and the four managed lanes.

During the environmental impact statement (EIS) process, the Harris County Toll Road Authority (HCTRA) expressed interest in participating in the managed lanes portion of the project. The EIS was modified to include tolling. Additional public involvement activities were conducted, along with a more detailed assessment of potential toll-related issues. Chapter Four, FHWA Program Guidance on HOV Operations, provides information on the issues to be examined when major changes in HOV operations are being considered.

There are two multi-agency agreements that have been used to date to advance the toll-managed lanes on the Katy Freeway. A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between TxDOT, METRO, and Harris County was signed in 2002. The MOU outlined the general roles of the three groups, specific provisions for transit, and the basic elements of the operating agreement. HCTRA is responsible for enforcement, incident management, and maintenance of the lanes. The MOU identifies a level of service (LOS) C as the target for the managed lanes. It also identifies transit access points, provides an option for future light rail transit (LRT), and allows special signing for METRO. The MOU also identifies the following elements in operating the managed lane:

METRO may operate 65 buses an hour, 24 hours a day/seven days a week (24/7) toll free;

METRO may operate METROLift service 24/7 toll free;

carpools with three or more persons (3+) may travel toll free from 6:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. and from 2:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m.

METRO support vehicles may travel toll free 24/7;

single-occupant vehicles, 2+ HOVs, and other vehicles pay the appropriate tolls.

The MOU also outlines the options that will be considered if a LOS C is not maintained. The potential actions include adjusting variable pricing, adjusting the HOV occupancy-level requirements, restricting METRO support vehicles, and expanding the facility to add transit-only lanes. METRO buses and METROLift vehicles are identified as the top priorities to continue using the lanes, followed by HOVs and non-revenue METRO vehicles are listed as the lowest priority.

The Tri-Party Agreement among TxDOT, FHWA, and Harris County was signed in March 2003. This agreement outlines the roles and responsibilities for funding, design, and reconstruction of the managed lanes. Harris County, through HCTRA, agreed to provide contributions equal to the construction cost, not to exceed $250 million. HCTRA is also responsible for design of the toll-related elements and any additional public involvement needed to consider the toll elements. The toll revenues will be used for debt service, reasonable return on investment, and funding operation and maintenance of the managed lanes. TxDOTís responsibilities include securing federal funding, the remaining right-of-way, and construction. TxDOT also agreed to provide it best efforts to meet the project schedule, including the use of incentives and other techniques.

Managed Lanes are also being considered in the Northwest corridor. A potential alternative in this corridor involves HCTRA purchasing an existing railroad right-of-way and developing a toll road and managed lane facility. Right-of-way would also be reserved for potential future LRT or commuter rail. Development of the toll facility may allow TxDOT to phase improvements to the Northwest Freeway over a longer period of time.

Future Directions

As noted previously, HOV facilities have been a key part of METRO, TxDOT, and HGAC plans since the late 1970s. Plans at the metropolitan level identified the candidate freeway corridors. As more detailed planning activities were undertaken at the corridor level, the location of HOV lanes, access points, park-and-ride lots, and transit centers were identified.

The use of the HOV and managed lane system in Houston continues to evolve through the coordinated efforts of various agencies and groups. Current TxDOT, METRO, HGAC, and HCTRA plans include expanding the HOV system, considering additional managed lanes, extending the initial LRT line, and developing new toll facilities. Plans, projects, and activities anticipated over the next five to 10 years are highlighted below.

Expansion of QuickRide. Activities are underway exploring options to modify and expand the QuickRide demonstration project. Elements being considered include modifying the user fees, changing the fee collection technology, enhancing enforcement capabilities, and expanding marketing and outreach efforts.

Expansion of the HOV System. The METRO Solutions 2025 transit plan includes continued development of the HOV system. Components of the plan include a 50 percent increase in bus service, 44 new bus routes, eight new park-and-ride facilities, and nine new transit centers. Many of these elements are part of the 250-mile, two-way HOV service included in the plan.

Additional Managed Lane Projects or Joint Toll Projects. Additional managed lanes or joint projects with the toll authorities are being explored. As noted previously, the Northwest Freeway corridor is being considered for managed lanes to be developed and operated by HCTRA in an existing railroad right-of-way. Reserving an envelope for future LRT or commuter rail is also planned. This approach could result in delaying improvements to the existing Northwest Freeway. It is anticipated that other corridors will also be considered for possible joint projects.

Light Rail Transit (LRT) and Commuter Rail. The initial LRT line is scheduled to open in January 2004. As of August 2003, the METRO Board was finalizing the 2025 transit plan, METRO Solutions. The plan provides the basis for a November ballot measure authorizing the agency to issue bonds. The rail element, which includes LRT and commuter rail, of the plan was scaled back based on public and political feedback. The current plan includes 22 miles of rail and a bond issue of $640 million.

Continued Toll Road Development. Both HCTRA and the Fort Bend County Toll Road Authority (FBCTRA) are moving forward with toll road projects. Future facilities may include toll roads and bridges, as well as joint projects with TxDOT and METRO.

Previous | Table of Contents | Next