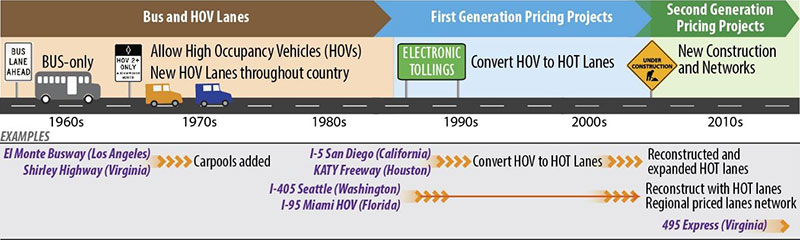

Report on the Value Pricing Pilot Program Through April 2018Chapter 1. IntroductionBackgroundCongestion pricing works by shifting some rush hour highway travel to other transportation modes or off-peak periods and by encouraging solo drivers to carpool. By removing a fraction (even as small as 5 percent) of the vehicles from a congested roadway, pricing enables the system to flow much more efficiently, allowing more vehicles to move through the same physical space.2 "Expanding the use of tolling and congestion pricing could help to reduce congestion, while generating revenues that could be used to finance the construction of new roadways and bridges or maintain existing facilities." Although drivers unfamiliar with the concept initially have questions and concerns, drivers who are more experienced with congestion pricing usually support it because it offers them a reliable trip time. Transit and ridesharing advocates also appreciate the ability of congestion pricing projects to generate revenue and the financial incentives that make alternatives to driving more attractive. The U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) report, Beyond Traffic 2045, cites congestion pricing as a potential policy option to "manage demand."3 The report also states that "Expanding the use of tolling and congestion pricing could help to reduce congestion while generating revenues that could be used to finance the construction of new roadways and bridges or maintain existing facilities."4 Through a comprehensive Congestion Pricing Program that includes the VPPP, as well as follow-on initiatives, FHWA has now funded more than 135 congestion pricing projects and studies across 21 States and the District of Columbia. This report represents findings from VPPP-funded projects, as well as extensive research on a variety of critical topics in congestion pricing. In the early development and application stages of the congestion pricing concept, multiple high-occupancy toll (HOT) lane projects encountered challenges and issues including equity, privacy, technology, and enforcement. Entities that are currently seeking to deploy congestion pricing strategies have benefitted not only from the research that DOT has conducted on these topics but also from sharing results across agencies and among industry partners. The FHWA provides critical support to States to help them implement strategies to manage congestion problems. More importantly, findings from deployed projects continue to demonstrate that the application of innovative congestion pricing strategies can efficiently manage demand on congested urban facilities. Because of successful deployments, there is growing consensus that congestion pricing is becoming a viable approach to reducing traffic congestion. Figure 1 depicts the evolution of managed lanes to priced managed lanes from the 1960s through today. In the early years of congestion pricing (1990s-early 2000s) in the United States, transportation agency staff that wished to explore such strategies faced skepticism or indifference within their agencies. Many innovative concepts incubated in the planning arena and took several years to develop into projects. Pilot program funding and support from the VPPP has helped significantly in the evolution from the bus and high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes to priced managed lanes, as shown in Figure 1. The VPPP has also contributed considerably to the accelerating concept development into the implementation of actual congestion pricing projects, often the first of their type in the region. These innovative strategies catch the attention of decision-makers and create desire to deploy similar endeavors.

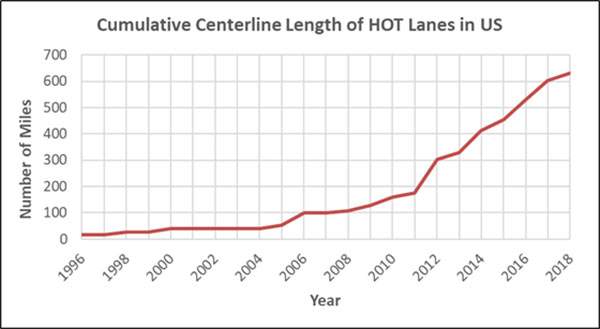

Figure 1. Timeline depicting the evolution of Managed Lanes from the 1960s through today. Pilot program funding and support from the VPPP has helped significantly in the evolution from bus HOV lanes to priced managed lanes 5 Figure 2 depicts the exponential growth of HOT lanes in the United States between the opening of the first projects in 1995 through 2017. The figure summarizes the deployment of HOT lanes only; however, all priced managed lane types, including express toll lanes, full facility tolling, and HOT lanes, have experienced a similarly rapid growth pattern.

Figure 2: Growth in the cumulative length of HOT lanes in the United States.6 Report OrganizationThis report provides an update on the various VPPP-funded or toll authorized projects and studies and discusses FHWA's recent outreach and technical assistance to advance congestion pricing beyond the current VPPP project locations. Finally, Appendix A provides a summary of the level of assistance each project received under the VPPP. 2 Federal Highway Administration, Congestion Pricing – A Primer: Overview, FHWA-HOP-08-039 (Washington, DC: FHWA, October 2008). Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop08039/cp_prim1_00.htm. Accessed 2/24/16. [ Return to Note 2 ] 3 U.S. Department of Transportation, Beyond Traffic 2045, Trends and Choices, 2015. Available at: https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/Draft_Beyond_Traffic_Framework.pdf. Accessed 2/24/16. [ Return to Note 3 ] 5 Adapted from D. Ungemah, "HOT Lanes 2.0 - An Entrepreneurial Approach to Highway Capacity," Presentation Slides for National Road Pricing Conference in Houston, TX, June 2010. [ Return to Note 5 ] 6 Texas A&M Transportation Institute, 2018. Data for 2018 only considers opened projects from January through April. [ Return to Note 6 ] |

| US DOT Home | FHWA Home | Operations Home | Privacy Policy | ||