Incorporating Connected and Autonomous Vehicles Into the Integrated Corridor Management Approach

The integrated corridor management (ICM) approach is based on three fundamental concepts: a corridor-level "nexus" to operations; agency integration through institutional, operational, and technical means; and active management of all available, and hopefully participating, corridor assets and facilities. Each of these concepts is described below.

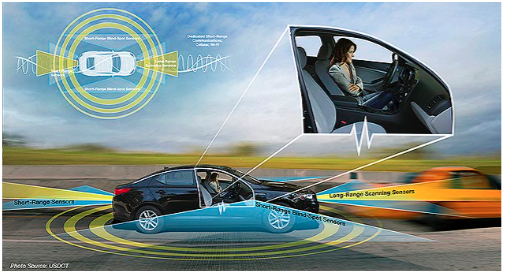

Figure 3. Illustration. Connected vehicles can help to prevent crashes at busy intersections.

Figure 3. Illustration. Connected vehicles can help to prevent crashes at busy intersections.

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation

A corridor-level focus on operations is a fundamental element of ICM. The United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) defines a corridor as a travel shed that serves a particular travel market or markets that are characterized by similar transportation needs and mobility issues. A combination of networks comprising facility types and modes provide complementary functions to meet those mobility needs. These networks may include freeways, limited access facilities, surface arterials, public transit, and bicycle and pedestrian facilities, among others. Cross-network connections permit travelers to seamlessly transfer between networks for a truly multimodal transportation experience.

Integration requires actively managing assets in a unified manner so that actions can be taken to benefit the corridor as a whole, not just a particular piece of it. Integration occurs along three dimensions:

- Institutional - Coordination and collaboration between various agencies and jurisdictions (i.e., transportation network owners) in support of ICM, including distributing specific operational responsibilities and sharing control functions in a manner that transcends institutional boundaries.

- Operational - Implementation of multi-agency transportation management strategies, often in real-time, that promote information sharing and coordinated operations across the various transportation networks in the corridor and facilitate management of the total capacity and demand on the corridor.

- Technical - The means by which information, system operations, and control functions can be effectively shared and distributed among networks and their respective transportation management systems, and by which the impacts of operational decisions can be immediately viewed and evaluated by the affected agencies. Examples include communication links between agencies, system interfaces, and the associated standards. This cannot be accomplished without institutional and operational integration.

Active management is the fundamental concept of taking a dynamic approach to a performance-based

process. Integrated corridor management requires that the notion of managed corridors, and the active management of the individual facilities within the corridor, be considered. It is expected that a managed corridor will have basic ITS capabilities for most if not all of the associated networks within the corridor. While not always synonymous with improved management and operations, ITS has proven to be a significant enabler of management and operations. ITS allows for the rapid identification of situations with a potential to cause congestion, unsafe conditions, reduced mobility, etc. and then allows for the implementation of appropriate strategies and plans for mitigating these problems and minimizing their duration and impact on travel. Such "management" may take the form of improved traffic controls, priorities for transit vehicles, improved response to incidents, and improved traveler information.

The Relationship Between Connected and Autonomous Vehicles and Integrated Corridor Management

ICM improves safety, mobility, and reliability and reduces emissions and fuel consumption by optimizing existing transportation infrastructure along a corridor, enabling travelers to make informed travel decisions. ICM involves a number of strategies to do this, including active traffic management, adaptive ramp metering, traveler information, incident response policies, transitonly lanes, transit signal priority, pricing and integrated payments, real-time signal coordination, and inter-agency information sharing, coordination, and collaboration. Many ICM strategies, e.g., active travel management and speed harmonization, employ advanced roadside technologies. The "hi-tech" nature of these strategies forms the basis of the relationship between ICM and connected and autonomous vehicles (CAV), and defines how the platforms integrate institutionally, operationally and technologically. A relationship is informed by the context in which the two entities interact. CAV has three factors that intersect and simultaneously form the basis for new mobility concepts available to the ICM community: the "car," the "industry," and the "driver."

- The Car – Cars are growing smarter and more efficient, connected, automated, and eventually autonomous. A key trend pushing CAV is the Internet of Things, which is the network of physical objects—devices, vehicles, buildings, etc.—embedded with electronics, software, and sensors that have network connectivity, which enables the collection and exchange of data. Next, the ways people and vehicles communicate are proliferating and getting less expensive, which means that connectivity is at a personal level at all times.

- The Industry – Vehicle manufacturers are responding to technology companies offering "carry-in" connected vehicle devices and apps. Their goals are to provide value-added services and collect data to improve existing services and offers. ICM operators are also witnessing a paradigm shift in terms of how data is collected and applied to management. Roadside data collection devices (loop detectors, pneumatic tubes, etc.) provided by intelligent transportation systems (ITS) manufacturers are now supplemented by smartphone and vehicle-sourced data collected and integrated by auto and tech-focused Silicon Valley companies. The latter data is more precise, personal, and can be turned in into actionable information quickly.

- The Driver – When force is applied to an object, it changes its attributes or direction. This applies to drivers, too. In the near future, CAV will make people to look at cars differently. Rather than buying and owning vehicles outright, people may tire of paying for and maintaining an asset that sits still 96 percent of the time and buy mobility services instead via a mobility-on-demand model. Even for those who drive their own cars, they will view them as spaces to consume media, make calls, and do other things made possible by CAV.

The first two factors are inputs that shape and enable CAV ecosystems. The third is an outcome—something to expect from CAV. The three factors encompass the key touchpoint between CAV and ICM, which is that CAV aids ICM goals. How well it does that depends on how well CAV is integrated into ICM from the institutional, operational, and technological perspectives.

Best Practices for Including Connected and Autonomous Vehicles Stakeholders into the Integrated Corridor Management Approach

As a technology-driven practice, ICM is well-positioned to include the CAV community among its stakeholder. Advances in technology already drive changes in ICM, and ICM operators constantly scan the technology environment to stay on top of advancements that improve corridor performance. ICM operators also incorporate strategies that include acquiring new technologies guided by best practices that take into account the impact that new technology has on the organization, customers, employees, suppliers, and other stakeholders. Including CAV stakeholders is an extension of those practices and therefore requires steps that overlap with how ICM supports the inclusion of new stakeholders, which is described below.

Building Interest

The ICM community must first care about the CAV community before including it among other stakeholders. There are several arguments for why the ICM community should be interested in the CAV community as a stakeholder:

- Innovation in Continuing to Contribute towards Enhanced Mobility – If ICM stakeholders are committed to providing safe, efficient, and healthy transportation services, they must be open to the idea of CAV proliferation, which is the next stage in mobility technology.

- Gaining First-mover Advantage – If ICM stakeholders that are currently ready to accommodate CAV do not make the voluntary move to advance the technology, then outside actors will fill that role and dictate how CAV contributes to ICM.

- Organizational Evolution to Accommodate the Future of Mobility Technology – If ICM stakeholders can manage the CAV revolution internally, they will more likely be able to control their role and destiny in the CAV ecosystem.

Building Champions and Stakeholders

Even when the rationale is understood, the integration of CAV into the ICM community requires support from internal and external champions and stakeholders — people and groups with a stake in the corridor and who are affected by its operations. Table 2 below defines the two groups.

Table 2. Definition of champions and stakeholders.

| Internal Champions & Stakeholders |

External Champions & Stakeholders |

|---|

- Within the primary organization that is developing or operates a system.

- Play a significant role in system function.

- Are significantly affected by changes in system design and function.

|

- Interact with organization and/or system but are outside the scope of both.

- Play a secondary role in organization and/or system function and are only affected by system function.

|

Internal champions and stakeholders count both the organization's employees and its management. External champions and stakeholders include both public and private groups. It is important to distinguish between them all because each has different motives and objectives.

Building Organizational Support

Corridors are comprised of discrete organizations that, while sharing the same high-level goal (improve mobility), have separate, individual challenges that they must overcome. However, by its very nature, CAV offers solutions for meeting many ICM stakeholders' business goals, such as increasing capacity, reducing accidents, or increasing revenue. In short, internal stakeholders must see that integrating the CAV community stakeholders supports their goals too. For stakeholder agency employees, incorporating the CAV community and technologies into operations and management activities can be presented as a way to develop new technical skills or as a form of professional development with promotional opportunities. To management, incorporating CAV into existing strategies or approaches can be presented as a means to demonstrate to external stakeholders an agency management's vision about the future of transportation and their willingness to innovate to improve it. It can be presented as evidence to the community that ICM leaders are open-minded. By integrating CAV institutionally, management is at the forefront of mobility technology and applications.

While the input, involvement, and support of external stakeholders are critical, ICM champions must emphasize that employees and other internal stakeholders hold the key to successful ICM. Therefore, each organization's credibility in the eyes of external stakeholders is proportionate to the extent that its mission, goals, and values are embedded throughout the organization. If internal stakeholders believe in the agency's policies and practices and support the organization in its strategic plan to integrate CAV, the more likely external stakeholders will be to support and assist with the process.

Aligning Resources

To influence internal and external stakeholders toward integrating CAV stakeholders into ICM approaches, involve them early in the process and present the positive (i.e., professional development, improved operations, better customer service, increased regional relevance) and cautionary (customers demand it; CAV is the next way to maintain service; if you don't do it, someone else will) arguments.

Next, demonstrate that the corridor is the ideal candidate for integrating CAV because it has the assets in hand to do so; namely, the technology resources, personnel resources, and Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) resources:

- Technology resources are the hardware, software, peripherals, wired/wireless communications services, power and data networks, etc. that corridors have deployed and that support the facility and the organizations from an information technology perspective.

- Personnel resources include the technical, administrative, policy, and managerial expertise needed to support the integration of CAV both internally (on the facilities themselves and their staff) and externally—i.e., the public (the public relations aspect of CAV).

- FHWA Resources like this document and other guides and educational materials are available to assist organizations with every step in the process.

The Two-Way Benefits of Incorporating Connected and Autonomous Vehicles into Integrated Corridor Management

The integration of CAV into ICM offers a number of potential cross benefits to ICM operators, suppliers, and users of CAV technologies:

- More Comprehensive Knowledge of Corridor Operations: A critical element in the management of transportation corridors is obtaining real-time information regarding current conditions and operations. To this end, monitoring capabilities are a vital component of ICM projects. ICM-CAV integration can lead to the greatly enhanced real-time data from CAVs and better information sharing between agencies that can yield a more complete picture of conditions. That data in turn informs traveler information, which can be sent directly, and in real-time, to vehicles and travelers who are using the corridor currently or who are planning their trips.

- More Efficient Operations: More knowledge of vehicle (single-occupancy vehicle and transit) and roadway conditions can improve ICM resource management. This can include short-term adjustments in response to incidents or longer-term adjustments designed to minimize the impacts of recurring conditions like congestion. Whether through enhanced knowledge about current conditions from direct CAV data or the implementation of various priority treatments – such as for transit and emergency vehicles – ICM-CAV integration can result in more efficient resource allocation and lead to a more reliable and safe corridor for all users, CAV-equipped or not.

- Better Informed Travelers: By collecting more comprehensive data on current conditions directly from vehicles and disseminating this information back to travelers in a coordinated manner, the traveling public can make more informed decisions about when and how they travel. This can lead to more efficient use of all parts of a travel corridor.

- Increased Transit Ridership: More efficient service, reduced delays, better incident response, and more information about travel options can make the corridor's transit components more attractive to potential users. Increased ridership also has secondary benefits, such as increased transit service revenue, reduced congestion, lower fuel consumption, and reduced emissions.

- More Efficient Implementation of Infrastructure and Improvements: Coordinated planning between agencies helps the ICM community identify opportunities where many improvements can be incorporated into the same design and construction efforts, and where key infrastructure may be installed to serve multiple goals. CAV data can help inform these decisions and help eliminate the redundancies that reduce disruptions due to construction (e.g., individual agencies making improvements separately on the same facility) and provide cost savings.

- Funding for ICM Improvements: A number of treatments that provide direct travel time benefits can be implemented as part of an ICM project. By participating in a coordinated initiative that integrates CAV into ICM planning and operations, the ICM community may be able to make stronger arguments for itself. For example, corridor stakeholders may be able to justify deploying Connected Transit Vehicle technologies for buses in order to feed real-time data into an ICM system. Additionally, they could work with local signal operators to request CAV-enabled advanced detection and signal systems on arterials.