Integrated Corridor Management, Managed Lanes, and Congestion Pricing: A Primer

You may need the Adobe® Reader® to view the PDFs on this page.

U.S. Department of Transportation FHWA HOP-16-042 November 2016 Table of Contents[ Notice and Quality Assurance Statement ] [ Technical Report Documentation Page ] List of FiguresList of Tables

INTRODUCTIONIn traditional urban transportation corridors, each transportation agency within the corridor typically handles operations independently. While the operators may collaborate or interact to some extent to deal with incidents or pre-planned events, each agency mostly conducts day-to- day operations autonomously. When congestion and the number of incidents increases over time, this method of operation becomes less effective in meeting the transportation needs of the businesses and people that rely upon the corridor. Who should read this primer?The intended audience for this primer includes stakeholders from State and local transportation departments, metropolitan planning organizations, transit agencies, and other agencies or organizations— public and private—that that may be involved in an ICM effort or in the implementation of congestion pricing initiatives. It is intended to encourage these groups to think broadly about the integration of congestion pricing that could significantly improve the overall effectiveness of an ICM corridor. The vision for integrated corridor management (ICM) is that transportation networks will realize significant improvements in the efficient movement of people and goods through the integrated, proactive management of existing infrastructure along major corridors. Through an ICM approach, transportation professionals manage the corridor as a multimodal system and make operational decisions for the benefit of the corridor as a whole. Congestion pricing is a means of managing traffic flow through pricing, thus harnessing the power of the market to reduce waste associated with traffic congestion. In this regard, both approaches aim to improve and enhance mobility options while addressing the menacing problem of congestion on the Nation's transportation network. ICM stakeholders typically include public transportation agencies, such as State and local departments of transportation (DOT), metropolitan planning organizations (MPO), and transit agencies. The ICM approach involves the seamless negotiation of jurisdictional boundaries and an approach in which operators take a corridor-level perspective on managing congestion as opposed to managing individual sections of the modally distinguished systems at the jurisdictional level. Its implementation inherently requires institutional collaboration and technology deployment to better manage the flow of goods and people. Congestion pricing also uses the network concept; congestion pricing involves deployment of tolling or pricing technology on the road network or parking systems. On dynamically priced facilities, toll rates are adjusted in real time in response to existing conditions in combination with predictive capabilities utilizing historical traffic trends and patterns.1 Congestion pricing can provide an ICM corridor with a technological and operational facility to manage traffic flow, including the potential to integrate technologically between networks or modal systems within the corridor. This primer will:

While there are limited examples of integrating ICM with congestion pricing strategies at the time of writing, the lessons learned from the current integration attempts may provide valuable input and direction to future attempts. Incorporating Integrated Corridor Management Into Congestion PricingThe ICM approach is based on three fundamental concepts: a corridor-level "nexus" to operations; agency integration through institutional, operational, and technical means; and active management of all available, and hopefully participating, corridor assets and facilities. Each of these concepts is described below. Corridor-level focus on operations is one the fundamental elements of ICM. The United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) defines a corridor as a travel shed that serves a particular travel market or markets that are characterized by similar transportation needs and mobility issues. A combination of networks comprising facility types and modes provide complementary functions to meet those mobility needs. These networks may include freeways, limited access facilities, surface arterials, public transit, and bicycle and pedestrian facilities, among others. Cross-network connections permit travelers to seamlessly transfer between networks for a truly multimodal transportation experience. Integration requires actively managing assets in a unified way so that actions can be taken to benefit the corridor as a whole, not just a particular piece of it. Integration occurs along three dimensions:

The Integrated Corridor Management Research Initiative

FHWA ICM Program Information:

https://www.its.dot.gov/icms/ FHWA's congestion pricing program resources are available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/congestionpricing/ resources/primers_briefs.htm The USDOT formally started the ICM Research Initiative in 2006 to explore and develop ICM concepts and approaches and to advance the deployment of ICM systems throughout the country. Initially, eight pioneer sites were selected to develop concepts of operations (ConOps) and system requirements for ICM on a congested corridor in their region. Three of these sites went on to conduct analysis, modeling, and simulation (AMS) for potential ICM response strategies on their corridor. In the final stage, two sites—the US-75 Corridor in Dallas, Texas, and the I-15 corridor in San Diego, California—were selected to design, deploy, and demonstrate their ICM systems. The Dallas and San Diego demonstrations "went live" in the spring of 2013. Each demonstration has two phases: 1) design and deployment, and 2) operations and maintenance. Both sites chose to develop a decision support system (DSS) as a technical tool to facilitate the application of institutional agreements and operational approaches that corridor stakeholders agreed to over a rigorous planning and design process. In 2015, thirteen other regional corridors were awarded grants to develop pre-implementation ICM foundations. Although the demonstration sites provide valuable insights into the necessary components of building an ICM system, they do not represent the only way to implement ICM. There is no "one-size-fits-all" approach to ICM, since the circumstances of a particular corridor will vary based on traffic patterns, agency dynamics, available assets, and a host of other factors. Thus, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is committed to raising awareness for ICM through their knowledge and technology transfer program, which advances the implementation and integration of ICM with other concepts. Congestion PricingGrowing congestion within the transportation network poses a substantial threat to the Nation's economy and to the quality of life of millions of Americans. Today, congestion occurs on more roads, more frequently, and for longer periods throughout the day, resulting in more required travel time than ever before. FHWA has realized the overarching negative impacts of congestion on mobility options, the transportation system, and the economy, among other aspects, and likewise undertaken significant efforts to promote innovative solutions such as congestion pricing to deal with this challenge. "Congestion pricing strategies can support regional goals by providing two direct benefits: improving multimodal system performance and generating revenues for transportation investments" Federal Highway Administration Congestion pricing offers a mechanism to correct this price differential and to account for the true costs of driving. Types of congestion pricing include:

Congestion pricing aims to change travel behavior by encouraging discretionary automobile travel to shift to other routes or to off-peak periods and/or incentivizing alternatives to single-occupancy vehicle such as carpooling and public transit. As early as 2008, it was recognized that by removing a fraction (as small as 5 percent) of the vehicles from a congested roadway, pricing enables the system to flow much more efficiently, allowing more cars to move through the same physical space. In fact, at that time, there was consensus among economists that congestion pricing represented the single most viable and sustainable approach to reducing traffic congestion.2 Congestion pricing projects continue to demonstrate the technical feasibility of pricing and have changed travel behavior.  Figure 1: Photo. Dynamically adjusted toll rate signs. Source: Federal Highway Administration Priced lanes have also proven that many travelers are happy to have the option of paying for a guaranteed reliable trip. Furthermore, support of innovative congestion reduction strategies through the deployment of priced facilities has created more efficient use of the transportation network that offers citizens the opportunity to reach services and jobs.3 Since the 1990s there has been a significant increase in priced managed lane deployments and significant efforts and interest at the Federal, State, and local levels in congestion pricing projects and studies in major metropolitan areas across the Unites States. As of 2016, there are 33 operating managed lane facilities nationwide, more than double the number (14) that were in existence when the 2012 FHWA Priced Managed Lanes Guide was written.4 FHWA anticipates that in the future, synergies among demand-based pricing approaches will significantly enhance the effectiveness of comprehensive and coordinated regional programs. As part of its integrated corridor management (ICM) project on I-15, the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) developed a smartphone application called 511 San Diego that makes multimodal, actionable traveler information available to the public, including:

The application also includes an optional text-to-speech feature and look-ahead commands that alert travelers to take alternate routes or modes to avoid congestion along their route. While the application is currently focused on the I-15 ICM corridor, SANDAG hopes to expand the program to other transportation corridors in the region. Source: http://511sd.com/app.aspx[ Return to Table of Contents ] INTEGRATED CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT AND CONGESTION PRICING"Expanding the use of tolling and congestion pricing could help to reduce congestion, while generating revenues that could be used to finance the construction of new roadways and bridges or maintain existing facilities." USDOT, Beyond Traffic 2045 Several metropolitan areas use congestion pricing to manage demand. Integrating an existing price-managed facility with the integrated corridor management (ICM) approach provides an opportunity to manage delay and maximize efficient use of the corridor's capacity through temporary route and/or mode shifts. In particular, variably priced lanes such as high-occupance toll (HOT) lanes and express toll lanes have strong potential to deliver greater service to users with an ICM approach by providing the option of diverting traffic to parallel facilities and modes or to the excess capacity available on a priced managed facility and under situations warranting such approach. Other pricing approaches such as road usage charging may also provide the ability to integrate with an ICM approach given the emphasis on network-based pricing. Congestion pricing may be implemented on an existing ICM corridor that has a managed facility (such as high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes) to enhance the travel options available to travelers and provide a priced option with reliable travel times. In this situation, ICM provides an institutional and technical platform for implementation of congestion pricing. The next section discusses the integration of the two strategies, beginning with a comparison of their goals and stakeholders and concluding with an examination of the benefits and challenges to integration. Congestion Pricing and Integrated Corridor Management GoalsImplementing tolling or congestion pricing can overlap with the goals of a corridor on which integrated corridor management (ICM) is being practiced and can provide the means for effective technology integration to better manage traffic flow. In many ways, the goals for both congestion pricing and ICM strategies are similar, as both aim to:

The effect of integrating ICM and congestion pricing is that they can work together for the ultimate benefit of the traveler, where ICM recommends a particular route (and provides information about that route) and congestion pricing ensures reliable travel time along that route.

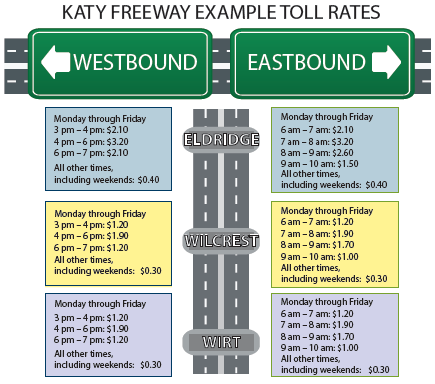

While congestion pricing uses variable pricing as a tool to achieve these objectives, ICM strategies aim to integrate networks and modes to achieve greater operational efficiency. Dynamically priced facilities adjust toll rates in real-time in response to existing conditions in combination with predictive capabilities that use historical traffic trends and patterns to project demand. Variable pricing diverts demand away from the facility and can also add capacity based on traffic conditions to maintain desired speeds, thus providing a more reliable trip time. ICM strategies focus on the operational coordination of multiple transportation networks and cross- network connections comprising a corridor, where integration along with data and information sharing maximize the effectiveness of operations and mitigate the effect of incidents that impact the movement of people and goods within the corridor.5 Congestion Pricing and Integrated Corridor Management StakeholdersInstitutional integration involves coordination and collaboration between various agencies and stakeholder groups in support of ICM, including distributing specific operational responsibilities and sharing control functions in a manner that transcends institutional boundaries. Understanding who the congestion pricing stakeholders are is the first step in identifying the appropriate participants to engage in ICM. Although certainly not limited to these, the stakeholders involved in congestion pricing in the existing ICM sites are the FHWA, USDOT, State agencies, local/county agencies, transit agencies, law enforcement, emergency services and private sector partners.  Figure 2. Figure. Solving congestion problems using integrated corridor management Different networks are operated in collaboration by different agencies and jurisdictions, such as State, county, city, and transit agencies. At typical integration sites, these agencies are represented on the ICM corridor's committees at the executive, management, and technical levels. These committees work collectively to arrive at the consensus on the development and operation of congestion pricing within ICM. The FHWA has a key role in the integration of congestion pricing into ICM sites by providing information about the benefits, challenges, and best practices to interested agencies and local coalitions. FHWA also aims to advance the state of practice in transportation corridor operations to manage congestion through its ICM initiative. This initiative provides institutional guidance, operational capabilities, intelligent transportation system (ITS) technology and technical methods needed for effective ICM systems. The State DOTs are the main stakeholders which usually undertake the construction, operation, maintenance, and data collection for the ICM sites with support from local or county agencies, cities, and transit providers. Transit agencies also play an important role in this integration by providing modal alternatives when congestion is present in the corridor. Private sector partners in communications, ITS, automation, and media are also indispensable as they provide and disseminate the information required to operate managed lanes simultaneously based on congestion levels and traffic incidents. In order to impact travelers' route choices, it is absolutely necessary to provide reliable travel time information to motorists as quickly as possible. Therefore, having the media and communications partners integrated and actively involved in the corridor management is crucial. Finally, actively engaging law enforcement and emergency services personnel in overall corridor management is critical as they are the front line for dealing with incidents and emergencies along the corridor and planning for special events which may impact corridor operations. Benefits of IntegrationMultimodal Mobility Benefits of IntegrationThe integration of congestion pricing into ICM planning and implementation provides many potential benefits to the stakeholders, road users, and to the economy, including:  Figure 3. Photo. Katy Tollway usage and hours of operation sign, with the Katy Tollway EZTag. Source: Federal Highway Administration

Toll-paying vehicles experience a reliable trip speed and travel time, which has a direct, positive impact on time available for work and leisure activities for the user and the reliability of deliveries for businesses, resulting in low transportation and inventory holding costs. Integration of congestion pricing to the ICM system increases the ability to manage demand and optimally utilize available transportation modes within a corridor to meet the demand. Integration of ICM and congestion pricing also provides the opportunity to enhance TIM within the corridor. In case of incidents, crashes, emergency, special events, or construction, dynamically adjusted toll rates help to adjust the traffic flow accordingly. Public transit systems benefit from the integration of congestion pricing with ICM, especially when combined with appropriate incentives in favor of transit and carpooling. Further, reduced congestion on the road improves public transit delivery, particularly for buses that share right-of-way with personal vehicles. Improving transit speeds and the reliability of transit service results in increased transit ridership and lower costs for transit providers. The I-15 Express Lanes (20 mile facility north of downtown San Diego) are an example of express lanes not in an ICM corridor. This example features four lanes with a movable barrier for maximum flexibility and has multiple access points to the general purpose highway lanes; and direct access ramps for high-frequency Rapid (bus rapid transit) service. The facility provides vanpools, carpools, buses, and FasTrak® (single occupant vehicles paying toll) customers with a smoother trip along the booming corridor; and also relieves demand on the general purpose lanes. As part of the San Diego Association of Governments' (SANDAG) ICM effort on the same segment of I-15, a 511 San Diego mobile application was developed that features real-time dynamic toll rates for the Express Lanes and predictive travel times, congestion information, and special event information for the I-15 corridor, in addition to traffic conditions, transit information, and more.6 Congestion pricing can also add to an agency's revenue stream when managed lane projects add new capacity to existing corridors. This revenue can benefit ICM when it is applied toward corridor maintenance, support for transit, and general transportation infrastructure improvements. It can potentially contribute to pay-as-you-go funding for incremental transportation improvements or be leveraged to finance significant capital investments that support the multimodal mobility goals of the corridor.  Figure 4. Illustration. I-10 Katy Freeway example toll rates. Source: Federal Highway Administration Overall, using congestion pricing as a strategy in an integrated corridor approach has the net effect of increasing person throughput through the transportation system and reducing congestion and delays on the road system. Ultimately, congestion pricing used in conjunction with ICM provides a mechanism to manage the capacity of the entire corridor more effectively. However, each site will have specific considerations for integration, and site-specific detailed analyses and research should be conducted to determine which of these potential benefits may be realized. User Benefits of IntegrationRoad value pricing in conjunction with ICM can influence travel demand at four different levels, optimizing travel flow and minimizing delays:

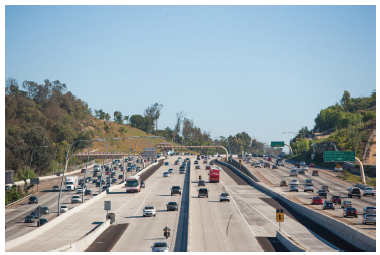

Figure 5. Photo. Managed and freeway lanes on I-15 in California. Source: Alex Esterella, SANDAG Integrating ICM with congestion pricing can help businesses lower transportation costs by reducing congestion-induced delays and resulting financial losses in terms of lost time and out-of- pocket costs for both individual travelers and businesses that rely on the transportation network for the productivity and timeliness of their employees and delivery of goods.7 Opportunities for IntegrationInstitutional IntegrationIntegration of ICM strategies with congestion pricing has the potential to provide the flexibility to set policies and strategies that maximize the throughput of the multimodal system from a corridor perspective, not inhibited by jurisdictional and agency barriers. Particularly in cases of incidents or situations of breakdown on any particular mode, congestion pricing has the capability to make excess capacity available to help flush the system and restore the flow of vehicular and transit traffic. Integration can also open up the potential for greater flexibility to set pricing incentives to optimize flow on particular modes or facilities. Integration can maximize system efficiency and has the potential to lead to better outcomes across modal agencies and, as such, be an attractive option to all stakeholders involved. Additionally, coordinated back-end operations including data gathering, payment processing, and performance monitoring and management has the potential to be a cost-saving measure for individual operators. ICM stakeholders can examine the potential for integration of electronic toll payment systems with transit payment systems to provide seamless transfers between modes and efficiencies in back- end operations. Greater ability to track transactions and payments can also lead to better tracking of violations and reducing revenue leakage resulting from them. The I-15 corridor in San Diego, whose ICM implementation is overseen by SANDAG, and exemplifies a multijurisdictional integration of several multimodal demand management strategies including pricing across multiple stakeholders. The corridor is situated within a major interregional goods movement corridor connecting Mexico with Riverside and San Bernardino counties in California as well as Las Vegas, Nevada. The management of traffic flow between the managed lanes (shown in Figure 5) and general purpose lanes is achieved by means of a coordinated approach among several of I-15 corridor's institutional stakeholders, including SANDAG, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and the California Highway Patrol (CHP). This corridor exhibits an excellent example of collaboration and partnership among various agencies. The I-15 Corridor in San Diego – Incorporating Congestion Pricing Strategies into an ICM Approach The managed lanes comprise a 21-mile long, four-lane wide facility within the corridor boundaries, as seen in Figure 5, with movable barriers that enable operations managers to configure the number of lanes in each direction to adapt to peak-demand levels. It uses dynamic variable pricing to determine tolls for I-15 FasTrak® customers (other than HOVs that use the facility for free.) High-frequency rapid transit vehicles operate in these lanes, enhancing regional connectivity. Incentives for van pooling, smart parking, ramp metering, and congestion pricing support demand management in the corridor. Revenues from toll-paying customers are used to help fund public transit in the corridor. In its 2015 Regional Plan, Sand Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) identifies a universal transportation account as part of its 30-year plan. A unified or universal transportation account as SANDAG envisions, will combine all forms of public transportation payments, including transit fares, municipal parking, and toll collection into a single user-friendly system. By offering rewards based on frequent use, toll discounts and other incentives, the system can lead to a shift from driving alone to using public transit. People will constantly receive information from the transportation network and be provided with the best options for their trips – based on their priorities, including cost, convenience, speed, and environmental impact. SANDAG is also deploying a pilot program for a smart parking system with incentive- based pricing for transit facilities to demonstrate the effectiveness of providing advance traveler information as to the availability and cost of parking and to encourage the use of transit services by offering credit-based pricing discounts to motorists using transit. Source: SANDAG, San Diego Forward: The Regional Plan, October 2015. Operational Integration Figure 6. Photo. MnExpress Lanes on I-394 Showing Rates. Source: Federal Highway Administration Transportations corridors usually possess excess and unused capacity along parallel routes, in the non-peak direction on freeways and arterials, and in transit, bus, vanpool, and passenger services. ICM strategies optimize the use of existing infrastructure assets and leverage the unused capacity by managing the entire corridor as one multimodal system rather than managing individual assets or standalone facilities.8 Congestion pricing has great potential to divert traffic and travel demand toward the transportation mediums with unused capacity by impacting drivers' route and mode choices. To improve the role of congestion pricing, ICM should provide travelers, including those en route, with enough information to allow them to envision the entire multi-modal network, allowing them to dynamically shift to alternative options. This will enable a traveler's immediate response to changing traffic conditions. For example, while driving in an ICM corridor, the traveler will be informed of congestion ahead on the route, and of alternate transportation options including priced lanes. They would also be able to access pricing information along with route information, nearby transit facilities, and timing and parking availability. In this manner, the enhanced level of service provided by congestion pricing within the roadway infrastructure will be leveraged by the ICM system. Improving congestion detection and routing along with incident management is crucial to help maintain the required level of service in the priced lanes so that the travelers will receive the value of their toll rate in terms of service. These improvements are combined with a significant and rich data set to develop strategies and scenarios that will enable real-time reaction and decision ability to enhance the operation of congestion pricing within an ICM corridor. It is important that partner agencies share their efforts to achieve such data sets and strategy development. Real-time sharing of information between agencies can help smooth the flow of traffic along a corridor. Agencies can make decisions in response to conditions and incidents, such as opening an express toll lane for all traffic for free in instances of extreme congestion. Such policy decisions can be made under an ICM framework to allow the flexibility to best utilize the available capacity under extreme circumstances. The Minnesota DOT (MnDOT) I-394 Value Pricing Program demonstrates how this operational integration of congestion pricing and ICM approach may be effected. The I-394 MnPASS express lanes opened in May 2005, as the MnDOT first application of HOT lanes on a segment of the I-394 corridor in the Minneapolis/St. Paul region. This system represents one of the first deployments of HOT lane strategies in the United States that dynamically adjusts pricing levels in response to varying traffic conditions (Figure 6). HOVs with two passengers or more, including transit vehicles, use the HOT lane facility at no cost while single-occupancy vehicles (SOV) use the lane by paying a toll that varies dynamically according to congestion levels. Minneapolis, St. Paul, MnPASS I-394 Value Pricing Program The ICM strategies on the corridor include an option to open the HOT lane to all traffic during major incidents. While the intent of the HOT lane is to maintain free-flow conditions for HOV and transit vehicles, there are some situations along I-394 that merit opening the HOT lane to all traffic to allow a "flush" of the vehicles. The decision to open the HOT lane to all vehicles would be based upon the location, severity, and duration of the incident. The following policies will dictate the course of action for the priced managed lanes in accordance with an ICM approach:

MnDOT has previously evaluated a short-term, multi-modal, integrated payment system in an attempt to combine HOT lanes, parking, and transit payments would simplify payment for travelers and also allow for innovative pricing incentives to encourage multi-modal use, such as credits for riding transit. Source: Minnesota Department of Transportation, MnPass Modeling and Pricing Algorithm Enhancement (Minnesota, May, 2015). Technical IntegrationEnhanced ITS and data collection methods are necessary to maintain the continuous integration of congestion pricing into ICM. With improved data, it will be possible to provide more reliable travel time information for each mode of transportation on each route. Improved algorithms are essential to effectively process such data and present the concluded information. Along with mobile phone and tablet applications, connected in-vehicle information systems are likely to play an important role in the near future to inform travelers about available options. These would greatly enhance the ability to communicate in real-time with drivers to make rerouting choices in ICM scenarios. A corridor-wide comprehensive information clearinghouse with the ability to collect data on the infrastructure status, including available capacity, demand, timing, and pricing will be required for efficient integration. Complete pricing data collection and information will require integration of traveler information systems providing pricing information for each individual mode. Modern managed lane facilities utilize a combination of static and dynamic message signs to communicate with drivers. Information such as eligibility (HOV, trucks, motorcycles, buses), toll rates (pre-set or dynamic), open/closed, and entrance/exit location is conveyed to drivers in advance of facility entrances, along the facility, as well as in advance of additional decision points for drivers. Combined with communications associated with the ICM operations, these DMS provide the ability to adjust messaging in real-time to advise traffic diversions related to ICM event scenarios. Integration of information related to managed lanes along with multimodal options would facilitate better decision making for the travelers and optimal flow management for operators. Information regarding out-of-pocket costs for comparable modes, including savings from incentives such as carpooling or ridesharing, will empower users with real-time information to make decisions regarding travel options. In promoting either the network or the modal shifts that are needed to optimize corridor throughput, an effective ICM strategy must address the convenience of travelers. A key component of this aspect is pricing and payment for transportation services. Integration of electronic payment methods across modes will help simplify payment methods and encourage multimodal use. This would involve integrating payment for priced lanes, parking, transit services, park-and-ride facilities, and other services that charge a fee along the corridor. It may also require integration of back-end payment processing and front-end customer-service. Such integration may also have the effect of reducing cost of processing transactions along the corridor. SANDAG's proposal of a universal transportation account is one example of agencies incorporating payment integration in their vision for multimodal transportation enhancement. Successfully achieving technical integration of ICM and congestion pricing solutions relies on availability of real-time transportation data from roadway instrumentation, transit, probe vehicles, or other means. Niagara International Transportation Technology Coalition (NITTEC) is proposing to combine dynamic fare pricing capability with interactive traveler information technologies, and has sought to document their approach in their concept for ICM in their region. The Niagara Frontier Corridor Niagara International Transportation Technology Coalition (NITTEC) initiated a Transportation Operations Study in 2007, providing support to NITTEC in the development of an ICM initiative on the Niagara Frontier Corridor. The Niagara Frontier, the border region that encompasses the Niagara River border crossings, is a strategic international gateway for the flow of trade and tourism between the United States and Canada. The ICM corridor is proposed to combine dynamic fare pricing capability with interactive traveler information technologies. This technology provides tailored information in response to a traveler request. Both real-time interactive request/response systems and information systems that "push" a tailored stream of information to the traveler based on a submitted profile are supported. The traveler can obtain current information regarding traffic conditions, roadway maintenance and construction, transit services, ride share/ride match, parking management, detours and pricing information. A variety of interactive devices may be used by the traveler to access information prior to a trip or en route including phone via a 511-like portal, kiosk, personal digital assistant, personal computer, and a variety of in-vehicle devices, to increase the effectiveness of value pricing on demand management. This also allows value-added resellers to collect transportation information that can be aggregated and made available to users on their personal devices or to remote traveler systems to better inform their customers of transportation conditions. By easily reaching this information, and with frequent access point provided, travelers will be able to make spur of the moment decisions to change their route choices. Successful deployment of this technology relies on availability of real-time transportation data from roadway instrumentation, transit, probe vehicles or other means. A traveler may also input personal preferences and identification information via a "traveler card" that can convey information to the system about the traveler as well as receive updates from the system so the card can be updated over time. Source: NITTEC Transportation Operations, Integrated Corridor Management: System Operational Concept, (June 2009). CHALLENGES TO INTEGRATIONInstitutional IntegrationThe primary barriers to the integration of congestion pricing with ICM are likely to be institutional. With multiple jurisdictions and stakeholders involved (as is typical for ICM coalitions,) issues of cost and revenue sharing can further complicate integration of priced managed lanes with ICM. ICM corridors that already have some form of managed lane facility (such as HOV lanes, HOT lanes, or express toll lanes) have the opportunity to incorporate congestion pricing in their operations. Investment related to congestion pricing implementation can be considered a long-term enhancement, similar to other fixed-guideway facilities (heavy and light rail and bus rapid transit (BRT)), in an ICM corridor. There may be barriers to traditional approaches of operating priced-managed lanes and ICM corridors which may require a fine tuning of objectives that meet the goals of both approaches. Managed lane operators may be reluctant to allow diversion onto their facilities due to concerns that it would drive traffic volumes beyond the managed lane's free-flow capacity and negatively impact customer experience. With the private sector becoming an increasingly important partner in building and operating managed lane facilities, the importance of a dependable revenue stream has come into focus. It is critical in an ICM corridor to carefully consider both ICM and revenue implications when setting the traffic and delay thresholds used to trigger traffic diversion onto the managed lane facility. In public-private partnership procurements, the private partner is likely to thoroughly assess this risk in advance and can negotiate the contractual terms with the public agencies. Payments can be pre-set in the contract to account for the potential revenue loss in ICM scenarios. Given the numerous partnerships and levels of cooperation and collaboration among various stakeholders in an ICM corridor, institutional issues are expected to arise as part of integration of congestion pricing into corridor objectives. In addition to preparation of legislative documents and protocols defining the integration, the legislative process and the process to reach an agreement between counties and cities on the same corridor also have the potential to cause disagreements that may eventually lead to delays in the project. Dealing with conflicting goals of partner agencies can be a significant challenge that may require changes in the project at various levels. The Texas DOT (TxDOT) "QuickRide" program on the I-19/Katy Freeway in Houston provides an example where benefits could be amplified through an expanded and active coalition of stakeholders. This program was anchored by Houston's innovative traffic management center, TranStar, and integrated multiple agency systems. However, the corridor perspective that the program targets could be strengthened by creating a coalition of actively involved stakeholders from these various agencies, providing greater visibility and sharing of ITS systems and data, and development of corridor-based performance monitoring. Houston, TX, HOT Lanes "QuickRide" Program on I-10/Katy Freeway The Houston, TX ICM application proposed I-10 and US 290, with US 290 as the north border, the West Park Toll Road to the south, and SH99 and IH 610 to the west and east, respectively, as their ICM corridor. The TxDOT Houston District was the lead agency, accompanied by the Houston Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County, Harris County, the City of Houston, and the Houston-Galveston Area Council. In addition to the expected freeway and arterial capabilities, the corridor includes HOV, tolling, value pricing, express bus, and BRT. Houston's ICM strategy includes a state of the art multi-agency emergency and traffic management center, TranStar. The links between various agency systems offer more opportunities to extend the regional ITS capability to span agencies, modes and facilities. These opportunities exist as a result of each agency concentrating on their core operational responsibilities and moving towards those goals. However, there is scope to effect better integration by establishing a corridor perspective among the TranStar partners and other stakeholders in the corridor. This could help achieve greater visibility and sharing of ITS systems and data, and development of corridor-based performance monitoring. An ICM coalition could explore combining the Automatic Vehicle Identification (AVI) system with Metro's transit ITS data, in order to increase the effectiveness of value pricing. Such an effort will result in a traveler information system that would compare travel time and potential costs associated with a choice between freeway general purpose lanes, dynamic priced lanes, HOV-carpool, or HOV-Bus Rapid Transit on both IH 10 and US 290. This feature would effectively help to divert the traffic on I-10 to arterials and I-10 managed lanes. Source: Presentation by John M. Gaynor, Director, Transportation Management Systems, Texas Department of Transportation, Houston District (Houston TranStar) to USDOT. Operational Integration Figure 7. Photo. FastTrack Express Lanes Pricing Information. Source: Federal Highway Administration  Figure 8. Photo. An example exit point from managed lanes. Source: Federal Highway Administration The key challenge with an existing priced managed facility is that an ICM approach may not always overlap with the goals of the existing priced managed lane. While ICM events that require facility managers to override existing congestion pricing principles may be intermittent, response approaches and policies need to considered and agreed upon ahead of time by all stakeholders to avoid conflict during situations that may develop quickly. The primary goal of demand pricing is to provide a "congestion-free" option for travelers who are willing to pay. The driving experience perceived by customers should be at least as valuable as, if not more valuable than, the toll paid. Likewise, operations are driven by the goal of providing a level of service, generally measured in terms of increased travel time reliability over general purpose lanes, that is perceived to be more valuable than the toll paid. For example, the FasTrak Express Lanes in the Bay Area (California), allow individual drivers to pay a toll to drive in express lanes, while carpools can travel toll-free. Presentation of FasTrak pricing information is shown in Figure 7. An ICM approach, on the other hand, takes a multimodal view and seeks to divert traffic and travelers to the most efficient route or mode based upon current conditions and asset availability. An event such as congestion in general purpose lanes due to lane closures or an extreme event would, under an ICM scenario, require directing traffic onto priced lanes if there is excess capacity available there in order to flush the system until congestion subsides. But such a diversion would compromise the rationale for collecting revenue for the time that the priced lanes are used to flush the system. The threshold for such instances and the response to the resulting situation of conflicting goals could be an operational challenge that needs prior determination of operational policies as demonstrated by the MnPASS I-394 example. Technical IntegrationThe process of integrating ICM strategies into an existing priced managed facility can encounter several technical challenges. Managed lane access points are of particular concern in terms of their frequency, capacity, design characteristics, and locations. As seen in Figure 8, design of access and exit points on managed lanes are quite different than basic lane changing practices. Access and egress points for managed lane facilities may not be located at points that are ideal for ICM operations. For facilities that are physically separated from the general traffic lanes by the use of barriers, raised pavement dividers, grade separations, or pylons (I-25 in Colorado, parts of I-394 in Minnesota, as examples), the effectiveness of utilizing managed lanes for traffic relief in ICM scenarios can be significantly limited. Many of these facilities do not provide access or egress at interchanges that are accessible from the general purpose lanes. There can be up to 10 miles between physical access points. Many have breaks in the barrier for emergency purposes, but those are designed for low-speed access for emergency vehicles. In these cases, if an incident on the general purpose lanes occurs just downstream of the manage lane access point, it may be unusable for several miles. Some managed lane facilities utilize reversible lanes in order to add capacity in the peak traffic direction. In an ICM corridor, there is an opportunity to reverse direction to respond to major incidents and events. This is most effective for planned events (e.g., sports, concerts, festivals) as there is time for all agencies to plan around this traffic diversion. However, it is very challenging to reverse direction in response to an incident. Some facilities in the United States use a movable barrier (I-15 San Diego, I-93 Massachusetts) to provide maximum capacity in the peak direction. While the process to move the barrier is considerably faster than lane reversal, it still has a significant impact on driver expectations, transit operations, emergency access, and maintenance. This option should only be considered in more extreme ICM diversion scenarios. Another challenge concerns the amount of information on signage in advance of managed lanes access points. Price-managed lane facilities are already faced with information overload on signage in advance of access points, as shown in Figure 9. Combining pricing strategies with ICM strategies could exacerbate the problem, as even more information needs to be conveyed to drivers. The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) has explicit limits on the spacing of signs and the amount of information to be placed on each sign.  Figure 9. Illustration. A dynamic traveler information sign that indicates travel time via high-occupancy vehicle lanes versus normal travel lanes. Source: Federal Highway Administration [ Return to Table of Contents ] SUMMARYICM is the result of a shared effort among public and private stakeholders that focuses on the efficient utilization of the transportation infrastructure and assets. As congestion continues to grow, and agencies' ability to expand the roadway network and transit is limited by both space and resources, ICM provides operators with a tool to maximize the capacity of existing roadway infrastructure through active management of all assets along a corridor. Table 1 summarizes both the opportunities for and challenges to integrating ICM and congestion pricing strategies. Note that there are no one-size fits all solutions to the challenges listed. The examples discussed in this primer that show how specific obstacles have been resolved can be used to inform effective policies and innovative approaches. Stakeholder perspectives are integral to mitigating common pitfalls that may be encountered during this process.

DMS = dynamic message sign

ICM = integrated corridor management Congestion pricing has a critical role to move transportation users along and around a corridor as efficiently as possible. However, congestion pricing by itself cannot be as effective as when it is integrated with an ICM corridor. Congestion pricing can provide an ICM corridor with the ability to manage traffic flow by dynamically pricing facilities to affect traffic. With dynamic pricing, toll rates are adjusted in real time in response to existing traffic conditions such that free-flow conditions are maintained on the facility and excess demands diverted to alternatives that have unused capacity. The integration of congestion pricing offers promising opportunities to cost-effectively reduce traffic congestion, improve the reliability of highway-system performance, and improve the quality of life for residents that experience routine traffic congestion. It also has the potential for providing a revenue stream to fund system improvements in the corridor. However, in all cases, detailed analysis is required to ensure that the integration will be beneficial for all the stakeholders including the public. Each implementing site will likely have different priorities, approaches, and stakeholder groups involved that should be considered and evaluated. There are also challenges to implementing congestion pricing in an ICM corridor. The up-front investment required to implement congestion pricing, combined with the general lack of public acceptance for paying for better level of service on a roadway that many feel they have already paid for through existing forms of taxation, can make it difficult for these initiatives to gain momentum. Additionally, the demographic, social, and economic profile of the corridor users are significant factors that need to be accounted for in planning the integration of congestion pricing with an existing ICM corridor. Lack of infrastructure, technology, expertise, and experience may also stand up as challenges to be tackled during the integration phase. Several of these challenges can be overcome through analysis and coalition building among stakeholders. The MnPASS lanes in Minnesota demonstrate the benefits to integrating ICM strategies on existing priced managed corridors and this can be implemented with consistent analysis of policies that would be beneficial to the goals of both pricing and ICM. In the case of implementing new priced managed lanes in an existing ICM corridor, a public-private partnership-based procurement provides opportunities for detailed risk assessment by private entities to ensure that ICM approaches do not adversely impact the congestion pricing goals. While this primer has presented examples of congestion pricing strategies that ICM sites could consider, it does not represent a "one size fits all" model; what works for one region may not work for another. In addition, ICM implementers should be aware of and prepared to address the institutional, operational, and technical barriers associated with these strategies. Overall, ICM and congestion pricing approaches both aim to enhance mobility options and improve system operations in a corridor and as such their goals align. Agencies should examine the opportunities for integration closely. Such integration, if executed successfully, has the potential for far-reaching benefits in terms of providing an efficient and reliable travel experience for all users on the corridor. 1 Federal Highway Administration, Priced Managed Lane Guide, FHWA-HOP-13-007 (Washington, DC: FHWA, October 2012). Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop13007/fhwahop13007.pdf. [ Return to note 1. ] 2 Federal Highway Administration, Congestion Pricing, A Primer: Overview, FHWA-HOP-08-039 (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2008). Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop08039/fhwahop08039.pdf. [ Return to note 2. ] 3 Federal Highway Administration, Report on Value Pricing Pilot Program Through April 2014, (Washington, D.C:FHWA, 2014). Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/congestionpricing/value_pricing/pubs_reports/rpttocongress/vppp14rpt/index.htm. [ Return to note 3. ] 4 Federal Highway Administration, Priced Managed Lane Guide, FHWA-HOP-13-007 (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2012). Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop13007/index.htm. [ Return to note 4. ] 5 U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and Innovation Technology Administration, Integrated Corridor Management: Implementation Guide and Lessons Learned, FHWA-JPO-12-075, (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2012). Available at: https://ntl.bts.gov/lib/47000/47600/47670/FHWA-JPO-12-075_FinalPKG_508.pdf. [ Return to note 5. ] 6 San Diego Association of Governments, "I-15 Express Lanes" web page, available at: http://www.sandag.org/?projectid=34&fuseaction=projects.detail. [ Return to note 6. ] 7 Federal Highway Administration, Congestion Pricing, A Primer: Overview, FHWA-HOP-08-039 (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2008). Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop08039/fhwahop08039.pdf. [ Return to note 7. ] 8 Federal Highway Administration, Priced Managed Lane Guide, FHWA-HOP-13-007 (Washington, DC: FHWA 2012). Available at: http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop13007/fhwahop13007.pdf. [ Return to note 8. ] | |||||||||||||||

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||